‘It was bibliophilia at first sight’ Slavs and Tatars on Molla Nasreddin

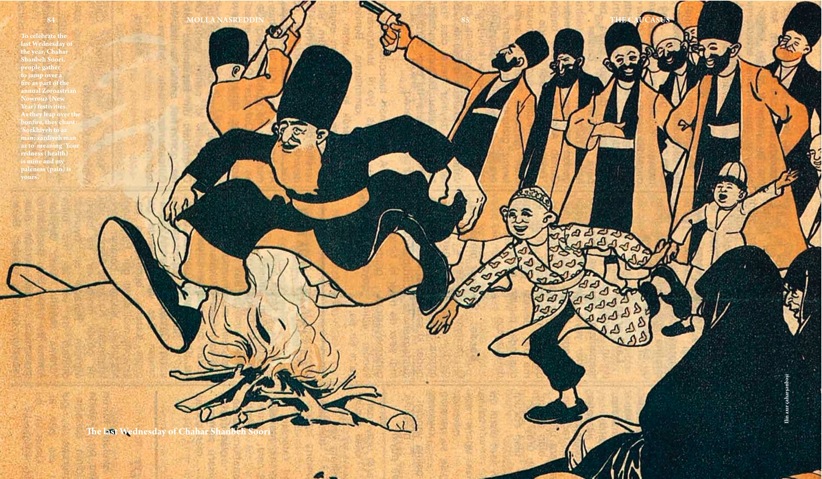

Slavs and Tatars is a collective founded in 2005, that addresses ‘a shared sphere of influence between Slavs, Caucasians and Central Asians’. Based in Brussels, Cambridge and Moscow, their work (often print based but also including performances and lectures) crosses trans-national borders by way of ironic polemics that, in their own words, ‘[re-claim] history by retelling it’. Their new publication Molla Nasreddin is a carefully re-edited reprint of the early 20th century eight page periodical published first in Tiflis, now Tbilisi Georgia (1906-1917) then in Tabriz, Iran (1921) and finally in Baku, Azerbaijan (1922-1931). The magazine consisted of columns, articles, cartoons, poems and stories and was founded by the Azerbaijani writer and publisher Jalil Mammadguluzadeh. It aimed to criticise social inequality, corruption, political and cultural short-sightedness, backward education systems and values. The magazine was an immediate success reaching a circulation of 5000 in its first months and was read throughout the Muslim world – a triumph almost certainly unachievable today.

Where did you find the originals of Molla Nasreddin?

We first came across the Azeri periodical Molla Nasreddin on a winter day in a second-hand bookstore near Maiden Tower in Baku, Azerbaijan. It was bibliophilia at first sight. Its size and weight, not to mention the print quality and bright colors, stood out suspiciously amongst the meeker and dusty variations of Soviet-style works in old man Elman’s place. We stared at Molla Nasreddin and it, like an improbable beauty, winked back.

Why now?

The short answer? We’ve been lugging the original volumes between Baku, London, NY, Brussels and Moscow and our arms are tired, if toned.

The long answer? If we are to believe the faulty theory that the West and Islam are on a collision course, we would do well to look at the only precedent in history where the ideas and peoples of both co-existed, in the Caucasus and across Eurasia. Azerbaijan’s progressive history and geographic position between Europe and Asia offer the potential for a truly revolutionary Islam where moderation, pluralism and politics are not mutually exclusive.

The book is divided into chapters ‘East vs West’, ‘Class’, ‘Women’, ‘Colonialism’… Can you talk a bit about how you chose the different categories and how you made the specific selection within the chapters?

We chose the chapters according to the major themes we saw popping up across the 3000+ pages we combed through across the first 5 volumes available in reprint (through 1922). After the Bolsheviks arrived to power in Azerbaijan in 1920, the quality of the publication worsened considerably, as the editors had to toe the party line so we concentrated on the first 3 volumes, published during a particularly tumultuous and productive period that saw the 1905 Tsar’s decree liberalizing the press in the aftermath of the aborted 1905 Russian revolution, World War I and a waning Ottoman Empire. We chose roughly 200 or so of the illustrations, caricatures, etcetera that we found most relevant to both a Muslim but also global audience.

Are you concerned with the responsibility of publishing political cartoons today, with recent controversy such as the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons?

We did have to exercise a certain degree of self-censorship as the periodical’s critique of Islam was sometimes too crude and simply too mean to include or highlight. Most importantly, Molla Nasreddin is a crucial example of self-critique as it was run by Azeri Muslims, so quite different than the case of the Jyllands-Posten cartoons done by outsiders.

How do you feel, as a collective, about Westernization? Is it an issue in this day and age? And, if not, is there a similar ‘threat’ (or to speak with Molla Nasreddin, a similar ‘saviour’)?

This is perhaps one of the more conceptually interesting aspects of this project. Standing squarely as a champion of secular, Western values, the weekly is in some sense a mascot, in reverse, of our practice. Where Molla Nasreddin is secular and pro-Western, we tend to err on the side of the mystical and one of driving concerns in founding Slavs and Tatars is the suspicion of the wholesale import of Western modernity (especially in the Eurasian region). But few people spend years translating, editing, funding and publishing a media with which they disagree. We have wrestled with Molla Nasreddin: like any object of intense interest, it both repels and attracts us. It is rare to embrace one’s antithesis but it definitely keeps you on your toes.

Molla Nasreddin: the magazine that would’ve, could’ve, should’ve, by Slavs and Tatars, ISBN: 978-3-03764-212-2 / in English / March 2011 / Softcover 240 x 280 mm / 208 pages / € 29,- / order information: JRP Ringier

Maxine Kopsa