Picpus: A Remedy Against Blight and Mildew

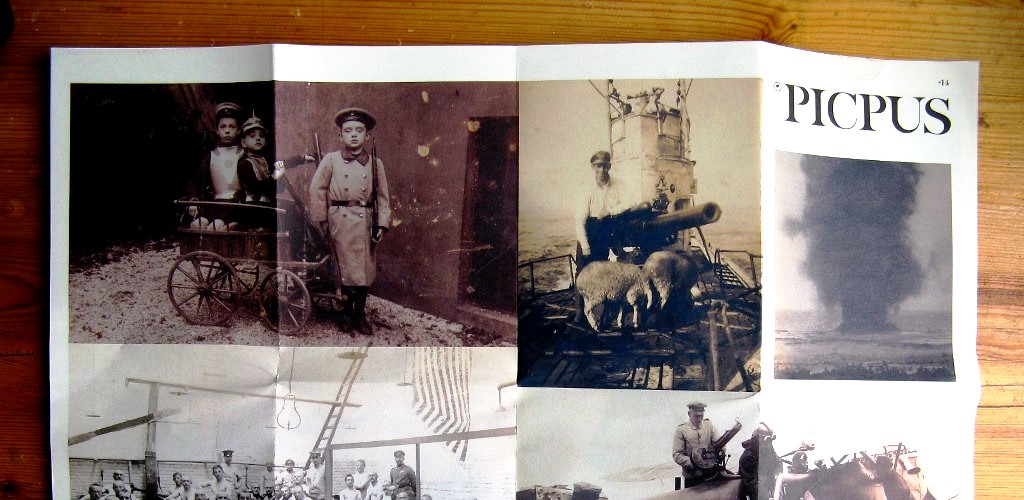

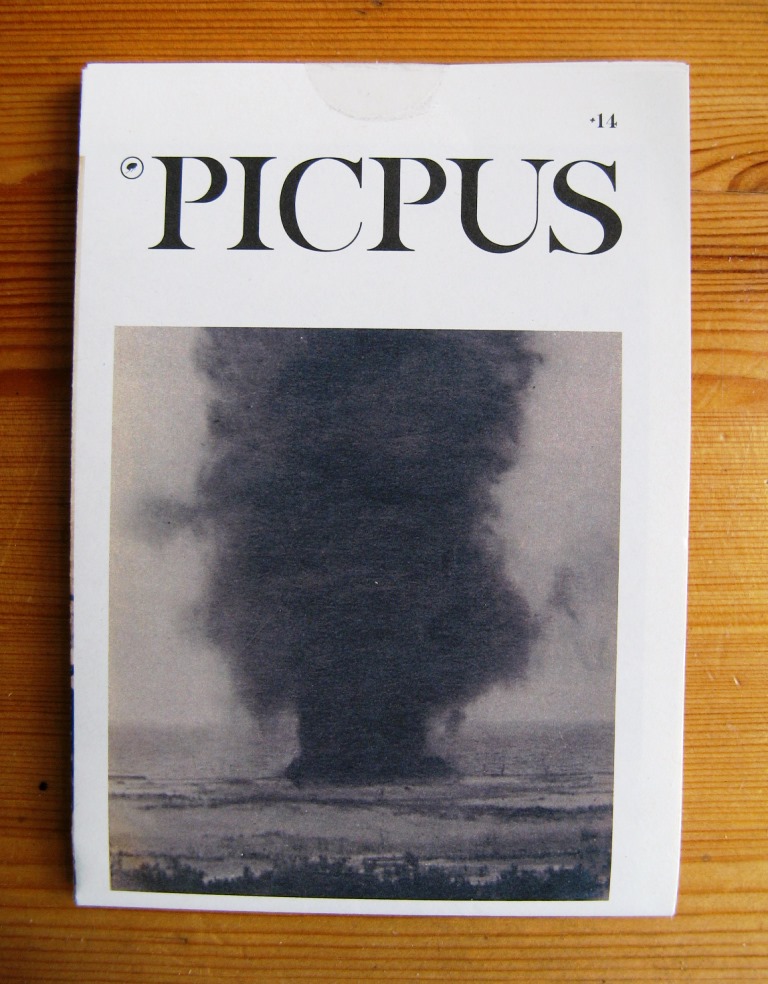

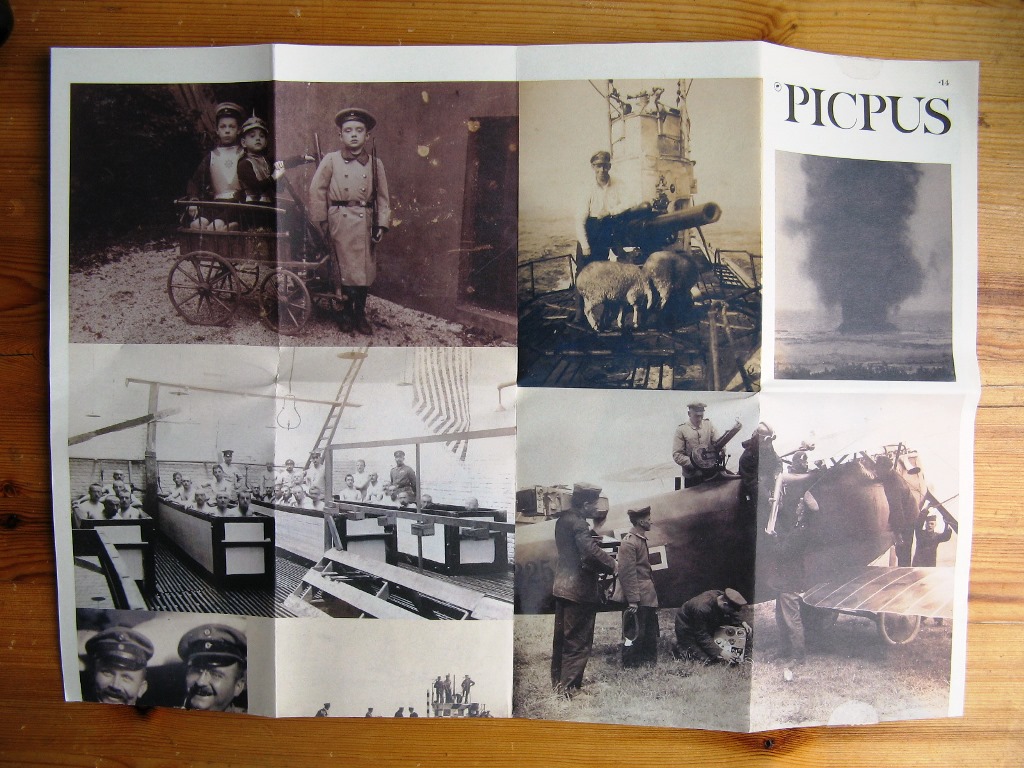

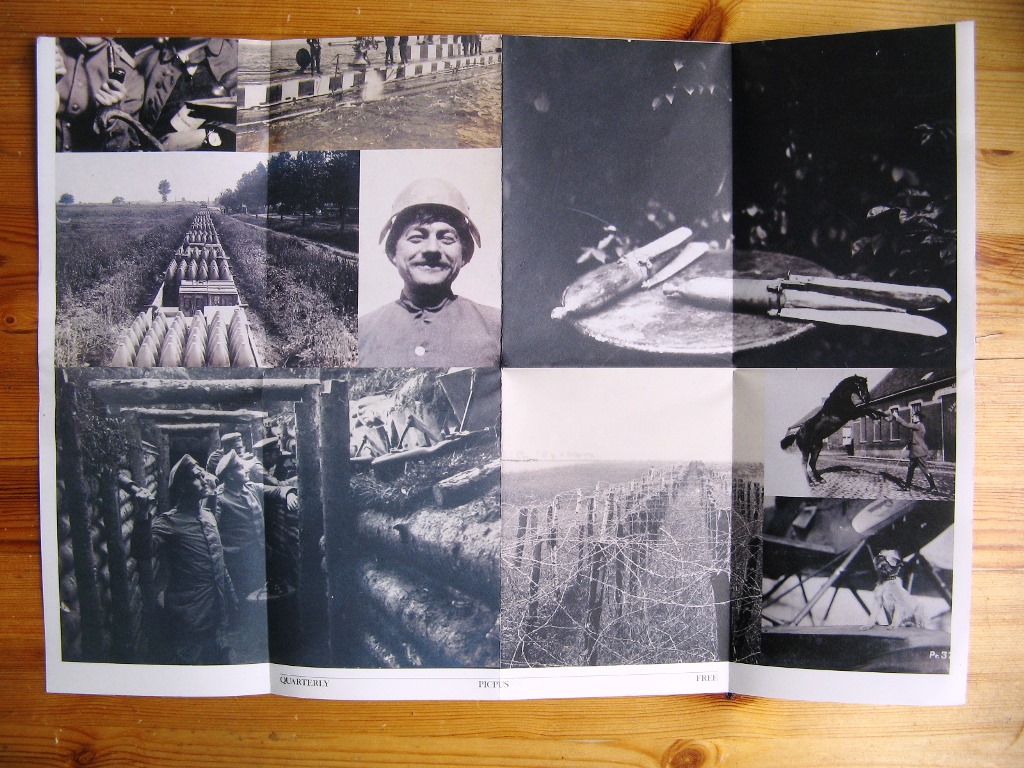

Picpus is a free magazine edited by Charles Asprey and Simon Grant. It carries transmissions from the art world, with a particular interest in historical curiosities, overlooked artists, and arts and politics. It is distributed through a selection of specialized art bookshops, galleries and libraries. The format of Picpus is the broadsheet, a single sheet measuring 60×42 cm, folded to the size of a postcard. The term broadsheet derives from types of popular prints usually just of a single sheet, sold on the streets and containing various types of material, from ballads to political satire.

When you type in the name Picpus and go to Google images, you will find magazine covers of Picpus in between photos of the Paris cemetery with the same name, where victims of the Reign of Terror in the immediate aftermath of the French Revolution were buried. Tell me about the name and the special format of the magazine.

The name of our arts journal is Picpus, thanks to the Scottish artist, poet and gardner Ian Hamilton Finlay. In many of his works the French Revolution features as a symbol of life’s extremes. A parallel is often found in his love of gardening, the taming of plants can be seen as a metaphor for terror and order.

Picpus is an area in Paris that in the 18th century was a destitute, God-foresaken part of the city. Robespierre buried many of his victims in pits in Picpus after they’d been executed by guillotine. The etymology of Picpus is possibly pique-puce or flea-bite and we wanted our journal to be a small but persistent addition to the art press discourse.

Finlay understood the power of paper to transmit ideas, I think this holds true even today in our culture now saturated with digital medias, and this is why Picpus is a paper journal. He also understood the message had to be transmitted by a beautiful combination of wording, typography and layout – we emulate this using a single sheet of A2 paper folded to pocket-size A6. This scale is crucial in that it ensures portability, provides just enough space for the information we want to print and looks totally different from the ubiquitous magazine formats. It feels elegant, desirable and perhaps by virtue of its scale, a little elicit.

Paraphrasing a subscription leaflet for Ray Magazine – a short-lived English avant-garde art magazine from the 1920’s – can I call Picpus a magazine of art-adventure?

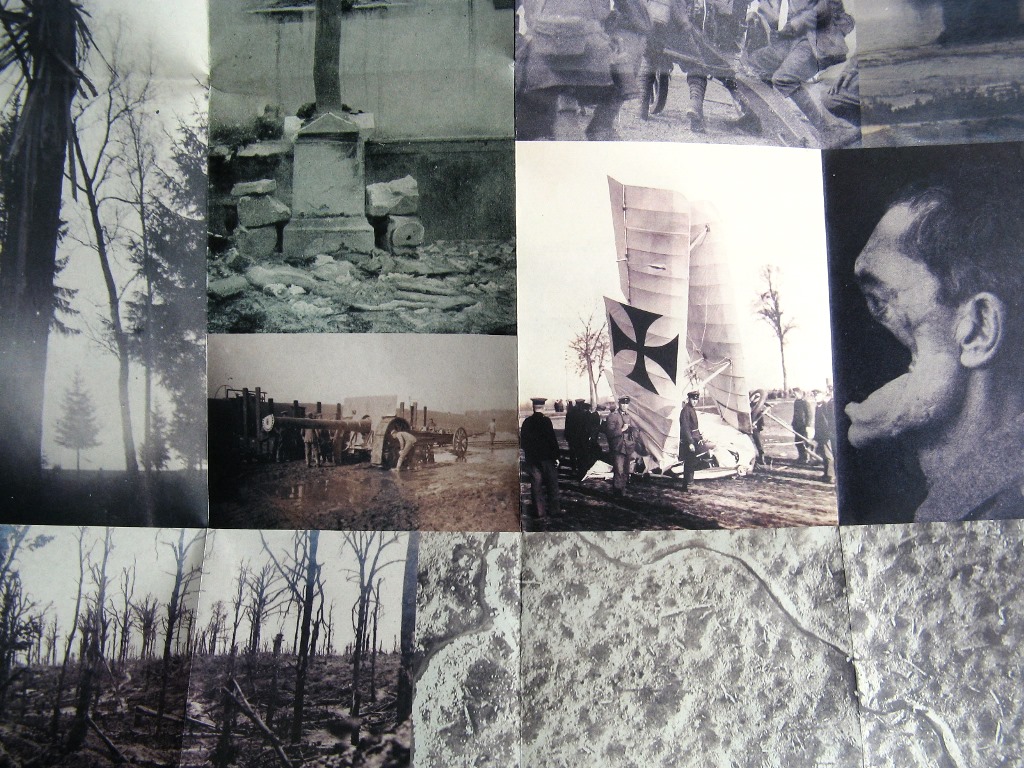

[answer Charles Asprey]Picpus covers a broad range of interests all loosely related to the arts. We are keen to encourage a return to story-telling, demand clarity in short texts which we illustrate with rare imagery. In addition we are not afraid to challenge artists or artworks that we deem deserving of a little contempt. The art press today is often too highly edited, feels filtered to a point of dryness and allows a certain language to prevail that is often adds layers of opaqueness to what is being described. We challenge all that in a small stylish package. I think my co-editor Simon Grant wouldn’t mind me saying that we deliver Picpus each quarter in many ways for our own pleasure. It’s the sort of art press we want to read!

In order that Picpus retains its independence and unique freedom of content and loose editorial approach it must be free

Why do you want Picpus to be picked up for free?

In order that Picpus retains its independence and unique freedom of content and loose editorial approach it must be free. Cost has had an impact on design of course but we feel the final product is a beautifully rare and uncompromised journal in the great tradition of these things.

Did you know the history of this format goes back to a Dutch newspaper called Courante uyt Italien ende Duytschlandt (Courant from Italy and Germany)? It was printed in Amsterdam, and carried reports about all of Europe, especially on trade, wars, and natural disasters. The oldest issue is from 14 June 1618.?

I wasn’t aware of the origins of this format in 17th century Europe but that’s fascinating. Clearly this method of distribution of knowledge still works.

And finally: every night before going to sleep I read a couple of pages in Sebald’s Bachelors: Queer Resistance and the Unconforming Life by Helen Finch on the work of the German writer W.G. Sebald. She arguments that Sebald’s queer poetics trace a ‘line of flight’ away from the repressive order. Can I call Picpus a ‘bachelor machine’ resisting the oppressive structures of the contemporary art world that is driven by big money?

I would rather describe Picpus using the body as a metaphor: Art History is the body, the great art movements or periods are the limbs, torso and joints. Picpus is, if you like, represents the invisible ligaments and cartlidge – the sinews that link the art events we’re so familiar with by revealing stories, events and situations that are crucial to the whole functioning of the body but are more hidden away or have become obscured by time and circumstance.

You mention Sebald – If there is any ‘resistance’ in us it is simply that we are perhaps, like Sebald in his Rings of Saturn book, more interested in the travels around the art world, the peripheral moments that we need to explore. We are only a two-man army!

THIS IS THE ORIGINAL VERSION OF THE INTERVIEW PUBLISHED IN A DUTCH TRANSLATION IN METROPOLIS M NO 3 – 2014

In the Netherlands PICPUS is available at Stroom Den Haag, San Seriffe Amsterdam and Printroom Rotterdama

Arnold Mosselman