Artificial Amsterdam

Opening today at de Appel in Amsterdam: Artifical Amsterdam, a show that presents Amsterdam as a city full of contradictions. What kind of contradictions? An interview with the curators Gerardo Mosquera and Rieke Vos.

The title ‘Artificial Amsterdam’ strikes me as an accusation, is it?

Gerardo Mosquera: No it’s a starting point. The title originated from my experience coming to Holland, and frequently finding the notion of artificiality reappearing. You arrive at Amsterdam Central Station and you smell pot, and see the red light district. But this freedom is regulated and only goes so far. Amsterdam is an old city, but it is exactly because this city is so organic and historical that it has turned into a tourist postcard.

Is this a nostalgic exhibition?

What is the urgency of organising this exhibition at this very moment?

Rieke Vos: We see how the city is being marketed. We have ‘Amsterdam 2013’, and ‘I amsterdam’, it is all around. That is not how you relate to a city, I don’t think anyone really does.

GM: I see an ideological shift taking place that is anti-intellectual and populist, and I think that the artistic environment has been affected by that to a great extent. When I was here in the 1990s the city was more tolerant and reactive, there was more room for experiment. There has been a conservative backlash. What I’m feeling here is that Amsterdam, and the Netherlands in general, is a place where culture is shown more than a place in which culture is created. It is more of a showcase than an oven. I am not saying nothing is happening, but the level of cultural tradition here has been moving more toward the display of magnificent programmes and big names.

How do the artists respond to this?

GM: Quite varied. This exhibition shows how different artists subjectively react to the city. There are works that were made specifically for this exhibition, and works dating as far back as the 17th century.

RV: There is a travel print from the 17th century showing Havana with gothic towers that were never there in real life. After eight weeks at sea the traveller projects his own memory onto the city. Even today the overregulated planned city is but a context on which every individual makes his or her own projection. For example, Inti Hernandez brings the floor of his kitchen in Havana to the Netherlands and introduces it here in the public space. A lot of works here are not directly about Amsterdam, but they are a response to the elements that strike you about the city, and how you play with that.

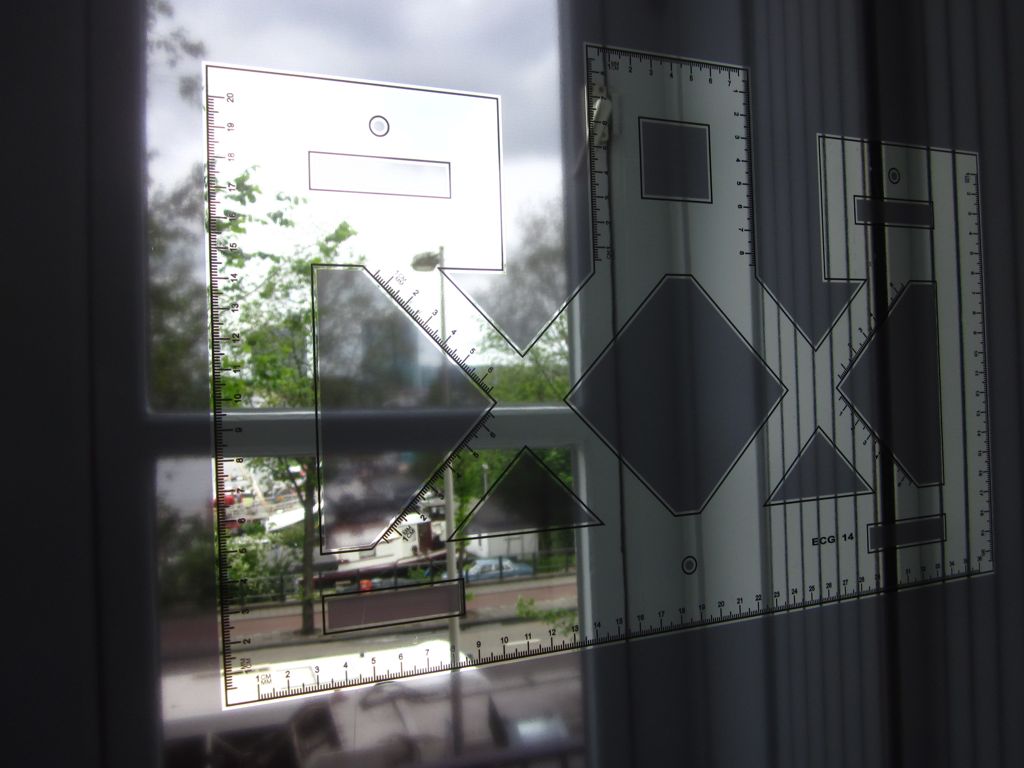

GM: This becomes clear in Carlos Garaicoa’s metaphorical site-specific intervention on the windows of De Appel. You look at the city outside through a grid of rulers in the shape of buildings. The fictional grid is there to measure and square the real world.

RV: In that sense the exhibition is also about the way we deal with our heritage. Barbara Visser made a tapestry depicting the old Roccoco interior of De Appel that is now in the depot of the Amsterdam Museum. It has not seen the daylight since the 1970s. Visser was not allowed to take it out of the crates, which is exemplary for how we handle our heritage. History is nourished, but at the same time locked away. Even though these interiors were originally meant for daily usage.

How should we interpret such a varied selection of artists from different times and places?

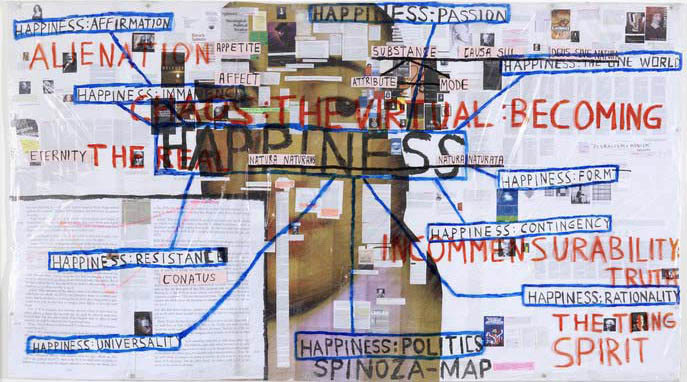

GM: We don’t try to tell a story here or have an encyclopaedic approach to the subject. It’s just some examples with which we try to build a discourse. How do artists now and in the past feel the city? It is more about emotions. For instance Orhan Pamuk wrote that Istanbul for him is black and white, like an old photograph. This is no urbanistic criterium but a feeling. In his polls about public reactions to the city of Amsterdam Silva kept asking questions like: is the central station male, female, gay? Or: what is Leidseplein’s colour? I thought about organising a show in which we could depart from such alternative parameters.

Amsterdam is supposedly a very open city, but a lot of art is behind closed doors. What should be the role of the art institution in relation to the public space?

RV: The original idea was to take the exhibition into the public space. There is an exhibition in the Oude Kerk and there are city walks and a Q&A, but within the budgets we are working with no more was possible.

GM: The goal was to have an exhibition about Amsterdam both here and in Amsterdam, and also have the city participating. I think we have to confront two main problems. One is the complicated and overwhelming grid of regulations here in the city. To do something in the public space is very difficult. The other problem was the lack of budget.

GM: Not at all. It is a comment on the way things used to be. In some cases we look at material related to the history of the city as a way for us to judge if the city has become more artificial. What happened here? But it is not looking back, it is a way to try and understand the contemporary city. To create historical narratives is to understand the present more than to understand the past.

Artificial Amsterdam

de Appel, Amsterdam

29 Jun — 13 Oct 2013

Hinde Haest