How to keep up with the past Laure Prouvost Interview

Since French-born, U.K.-based artist Laure Prouvost (°1976, Lille) won Britain’s prestigious Turner Prize for her video-installation Wantee (2013), she has been caught up in a whirlwind of attention. In the late afternoon sun, however, on the rooftop of Kunsthal Extra City in Antwerp, it is very quiet. A good opportunity to venture into Prouvost’s enigmatic world of erotically-shaped tea pots, surreal fantasies and muddy paintings. Both Wantee and Prouvost’s complementary film Grand Ma’s Dream (2013) are now on view at Extra City’s cinema.

At Extra City you show the film Wantee, which takes the viewer in search of your conceptual grandfather, a friend of Kurt Schwitters, lost in a tunnel. At the Turner Prize the jury praised the work as a ‘complex and courageous combination of images and objects in a deeply atmospheric environment.’ Yet, your current presentation is more a screening than it is an immersive installation.

How will it evolve in the coming months?

When I showed my films at Tate Britain it was in response to the history and legacy of Kurt Schwitters. It was more a dialogue with an actual show, prompting questions on how to make a comment about somebody’s work without being illustrative. It was also a good start to talk from my grandparent’s point of view. At Tate the film was presented like an installation, with tables and objects from the actual film. It was an attempt at creating a proximity, showing the audience that it’s all right here in front of you. You can actually touch the teapot, it’s a real story. Bringing the relic of a work, for me, is to prove that there is a reality. But I’ve also shown the film as screenings in different environments. Here, I was a little bit struggling about how I would present the films, but the idea was very much that it would grow.

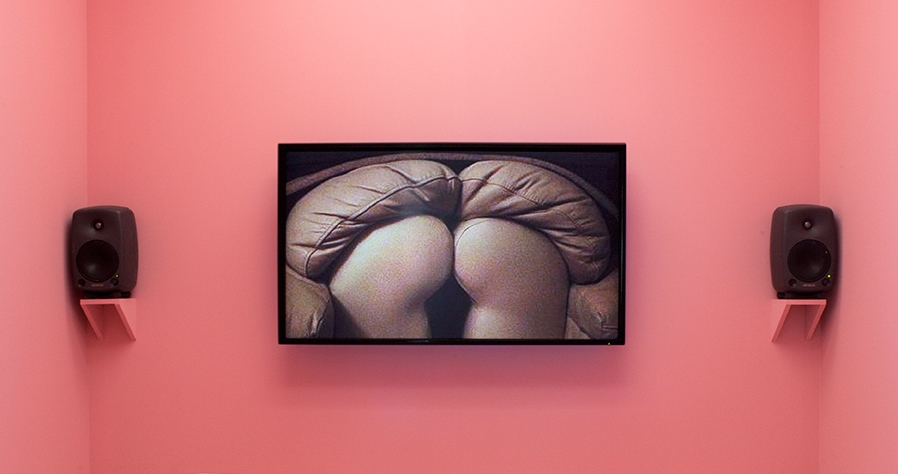

The pink room where I show Grandma’s Dream is similar to the presentation at the Turner Prize. I wanted some kind of a counterpart: the grandmother, the feminine, the struggle, the relationship in this period of time when it was all about the male, the master. My grandmother loves pink, she’s full of cliché’s. I didn’t want to make a feminist comment, but it was more about bringing two sides of a story.

Whilst exploring the slippage between fiction and reality, where does memory come in?

In this case, it’s about historical memory: how do we keep the past, how do we take care of it and how do we change it? Kurt Schwitters’ body of work is now perceived so differently than in he’s time, because a change of attitude towards everything what happened in between. It’s also about how the artist loses control with time and with a situation. Now I’m in Belgium, but before I was in England where the work is quite cultural: it’s in English, it’s about tea, about Wantee. It’s about being part of this English heritage and misunderstanding it because the protagonist is also a foreigner. Now we’re in Belgium, what does it say? It has all these layers which can be questioned. Wantee is questioning a lot about misunderstanding, like grandma is misunderstanding the work, she finds it very annoying, she wants it to be useful instead of conceptual and elitist. At the same time it’s about understanding things differently. Not understanding it wrong, but letting your imagination create something else.

In your installation For Forgetting (2014) at the New Museum in New York there was a quote, which especially caught my attention: “Just hold on the images”. Do you think you should rely on what you see for yourself, rather than base yourself on realities mediated by others?

[answer Laure Prouvost]In some ways my body of work started with The Artist and then Wantee, Grandma, and it grows as the story of my grandparents, the story of history, and of misinterpreting it. It’s about how history is misguiding us through what has been all made up anyway. In For Forgetting in New York it was more about the idea of how we go down the street, see this building that you can’t remember it was there before, and how things change over time. It’s obvious, but also striking how all these images layer on top op each other, causing us to forget what we’ve seen before. But it’s still there in the subconscious…

I quite like sensational memories. It’s the same with images: you compare the image with something you know you’ve seen

…and sometimes it pops up again?

Yes! I quite like sensational memories, like when your mom picks the ‘best’ raspberry for you to eat, and the taste of this one ‘best’ raspberry will always be compared to any other raspberry you’ll eat. It’s the same with images: you compare the image with something you know you’ve seen. The brain always compares anything we see unconsciously. And “hold on the images” which came from the video How to Make Money Religiously, is based on this idea of images making up your own reality, how they relate to memory and forgetting. It’s about how powerful you can be just looking. You will be rich of images, rich of feelings, and you should hold on of it, take it with you, and it will add up. It was not so much about the idea of money as a currency but more seeing an experience. You don’t need to own it physically, but you can be fulfilled by having these images inside your head.

In a way, it is really hard to digest your films, because the fast rate of the editing and all the images layering on top of each other. Rather than a linear narrative, you create a chain of images out of which the viewer can extract his own story. How do you build your structure?

In Wantee there are three chapters: the living room, granddad’s story and grandma’s tea party. How you keep the past and how you would add a history and make it more real. It is like how people keep the famous artist’s studio, it is taken care of very well, but it’s completely wrong, because the artist is not there, but thats how we control it. There is usually some sort of section and I know what I’m trying to to say even if the images contradict it. Sometimes I use the same images from one film for another and I’m interested in how each image can get a new meaning each time, it’s used with a different sound, a different story, they are very fragile and they can mean anything. In How to Make Money Religiously I had a few chapters: in the beginning it had to be this action – “you need to this, you need to do that and don’t forget this!”. Sometimes you wonder if you’ve already seen the same. At the beginning there is a lot of thing I shot in Naples. There is definitely an archive of video, which is very disorganized and where I don’t find anything. I film quite a lot and then I see what could work. But if I need a shot of someone jumping on a bus I will go and find it. Often I know what I need. If I need the sea I go and look what I have.

I like it how you often appear in your films, but still remain invisible. It’s just the hands, the whispering voice, the head veiled in a paper mask.

Yes, I appear quite a lot. If I need a hand caressing something, I will do it myself. I film myself but I don’t show myself. I always wear a mask. Or in Monologue (2009) I cut my head off in the camera frame. This was more about the idea I quite like that the viewer creates the character. There’s a voice which creates a phantasma, and the viewer finishes the image. You always grab what you can to make sense of what you see. That’s filmmaking at the base, but I hardly shoot people.

At Extra City you attempt to re-imagine the configuration of Extra City’s cinema over a longer period of time, disrupting the convention of film screenings. To what extent do cinematographic codes inform your practice?

In some way I come from an experimental cinema background. For many years my work was shown as screenings or in cinema contexts with a very specific audience. I think playing with the position of the viewer and the maker, constantly bringing it in, and questioning it is something that experimental film had embraced for a while. I’m definitely interested in the medium cinema and my film Monologue talks very much about the screening space. Here, I don’t really care. Im’ going to change it and add layers, bringing in a muddy painting that I found at my granddad’s, or maybe I will bring in a duck. My grandma has one, let’s see if she agrees to lend it.

Does your grandma appreciate your work?

She thinks it’s very useless and gossipy, she’s like “leave us alone”. But at the same time she was happy when I did her dream. I think in the future I may ask her to do my interviews, because she’s more articulate than I am. She’s not shy at all, she really gets going sometimes.

It’s fascinating how your films succeed at bringing about synaesthesia and multi-sensory experiences. It shows the viewer that images can be experienced in many different ways.

I like it when people say “oh, your films stink.”

[answer Laure Prouvost]Exactly: going to the market and experiencing just a smell, seeing art and listening to music. There’s not just one thing. I quite like this bubble of experience and it’s hard to pinpoint where something coming is from. The smell of a squashed tomato on the floor can bring about a whole chain of memories. Even if you don’t smell the tomato in my film, you see the smell, your memory will trigger it. I like it when people say “oh, your films stink.” I like bringing in another sensation with only pixels. Also the internet, where our information comes from. One project I did was about the wrong communication, miscommunication, we are not always so efficient. We all have our own history, you can hint things through images, most of us will recognize it and know what it tells , but it’s still a flat image.

Your images, be it a pixel or a sculpture, wouldn’t have such an impact on the audience if it wasn’t for the whispering language and the soundtrack enhancing the specific atmosphere.

I think I work more on sound than image actually. Everywhere you are, you can film something and it might become something else. I work a lot with sound because it uses a lot of the subconscious. Now that we are talking, we don’t hear the people behind us speaking, because our brain has decided not to focus the attention on anything else than our conversation. So the perception of sound is very unconscious. It is there, but you can’t pinpoint it. But maybe I talk a bit too much, you should stop me.

How important is philosophy or critical theory?

My grandparents read a lot and told me about it, but I mostly build my work from my personal experiences. In Monologue it’s about my mother talking to me about the speed of light and how we always miss each other a tiny fraction of a second. We never see each other in realtime, but that’s her story, I don’t know if it’s true. It’s more about what people tell me, then theory comes in, I misunderstand it and try to make sense of it. We all have that. Even if we read a lot, we always derive our own version of it, or we unconsciously choose what to remember.

You are currently in residence at AIR Antwerpen for a period of five months. What are you working on?

Here, at Extra City, the idea is that the show will grow, so I’m going to bring some paintings my granddad made some time ago. My grandmother found them a bit boring and tried to improve them, so she added a little bit of sand and some water. Furthermore, I will add some mud paintings and some new elements to make the story a bit more clear. Next week I will be in Naples where I will open a large video installation called Polpomotorino. In June I will have an opening at the gallery MOT International in Brussels and at the New Museum in New York I will do a performance, and two other performances mixed with video and music (From the Sky) at the Danspace Project at Saint Marks, curated by Fionn Meade.

Looking forward to all that.

Laure Prouvost

Extra City, Antwerpen

5 april t/m 25 mei

Laura Herman