After Crimea

How a part of the Russian art world responds to Crimea’s annexation by Russia. For example The Kandinsky Prize (The Russian The Vincent).

In December Andrey Filippov was announced winner of the Kandinsky Prize. The main project awarded was shown in the artist’s retrospective Department of Eagles at Ekaterina Foundation, Moscow, in March-April. The highly ambiguous show did not get much response from the media except for a few small reviews and an interview. The installation which was awarded the prize is dedicated to Crimea and was made a year after the annexation of this Ukrainian territory by Russia.

The Kandinsky Prize is the main award in the field of contemporary art in Russia. It is a private prize and the institution is a rather closed affair: you never know how the machine works, and who is making the decisions. For sure, the Kandinsky Prize is in many ways more contemporary than many other prizes. Maybe because the owner of the prize, the oligarch Shalva Breus, his advisers, assistants and partners are doing their best to be contemporary . The history of the Kandinsky Prize begins with the first winner Anatoly Osmolovsky in 2007. This edition was partly sponsored by the Deutsche Bank and testified to a fresh look on the Russian art scene; a bit like that other famous private initiative that started around that time: the Garage Museum. (read more about it in Metropolis M, No 4 – August-September 2015.) But all of this positivity came to a standstill due to a scandal surrounding the second edition:he 2008 prize laureate Alexey Belyaev-Gintovt didn’t even make an attempt to hide his extremely Right-wing position. For part of the audience it was an unpleasant surprise, for others it just showed how this kind of rhetoric and aesthetics are really part of the state of mind of the contemporary Russian elite. This turned out to be more than true in the years to come.

To avoid similar scandals in the future, the Kandinsky Prize decided to award the prize only to more or less “retired” neutral artists who have a history of achievements in art but are not so active at the moment of receiving the prize. They have awarded Vadim Zakharov in 2009, Alexander Brodsky in 2010, Yury Albert in 2011, Grisha Bruskin and AES+F in 2012, Irina Nakhova in 2013 and Pavel Pepperstein in 2014. Most laureates are part of the Moscow Conceptualism movement, except for Brodsky who was an “non-building architect”, the group of video artists AES+F and Bruskin who was given the prize, frankly speaking, because of his close friendship to Shalva Breus.

That’s why it wasn’t a surprise when Filippov got the prize this time around. He is part of the second generation of Moscow Conceptualists working very intensively in the 1980s and 1990s. His contestants were, among others, Elena Elagina and Igor Makarevich – the artist duo of the same generation and same community working with the same topics and figurative vocabulary.

The general line of Filippov’s artworks is based on the imagination of Russian geopolitical thinkers who, from the very early centuries until now, have invented several concepts to explain and legalize the domination of the Moscow Tsardom, the Empire and, then, the URSS. The first concept of this kind is “Moscow as the Third Rome” formulated by a XVI century monk Filofey: “Two Romes have fallen. The third stands. And there will be no fourth.” This ideological construction had lots of consequences in the long run – from a claim of the Russian state to rule the whole Christian world, especially the area with prevalence of Orthodox Christians, to the apocalyptic stand that Russia is the last fortress against the Antichrist’s advent.

This complex of ideas has influence Russian society on all levels and allowed the ruling class not only to surround itself with nationalistic building processes but also to oppress any attempt at strengthening human rights and freedoms, maintaining an obscurantist atmosphere and wage endless wars with neighbouring countries aimed at expanding the regime in all directions, especially in the symbolic direction of Istanbul, an unachievable goal for all Russian rulers from Grand Dukes to Joseph Stalin.

I should especially make clear that in the Soviet period not only democratic opposition (dissidents) confronted the existing order of things: many different groups oppressed by the government and the party also resisted the oppression. Sometimes religious communities stood up against the regime even more strongly than others and their ideas widely spread among the whole protest movement. For example, the founder of one of the underground magazines, Dmitry Volchek testified in an article that members of radical Christian sects who didn’t accept Soviet laws which they considered diabolical, intensively cooperated with the dissidents’ press and anti-Soviet democratic groups.

For Andrey Filippov, it was extremely important that he is not only an artist and member of the non-official cultural community but also an Orthodox Christian – it is a part of his identity which he still mentions all the time. It explains what he is doing and why. His early artworks were based on a semi-anagrammatic trick: he changed the official slogan “Peace to the World!” (in Russian: Miru – mir!) into “Rome to Rome!” (Rimu – Rim!) which sounded quite absurd but made clear where his loyalties were. The artist reproduced this slogan many times in different media, from his first banner piece (1983) to silk screen prints (1990).

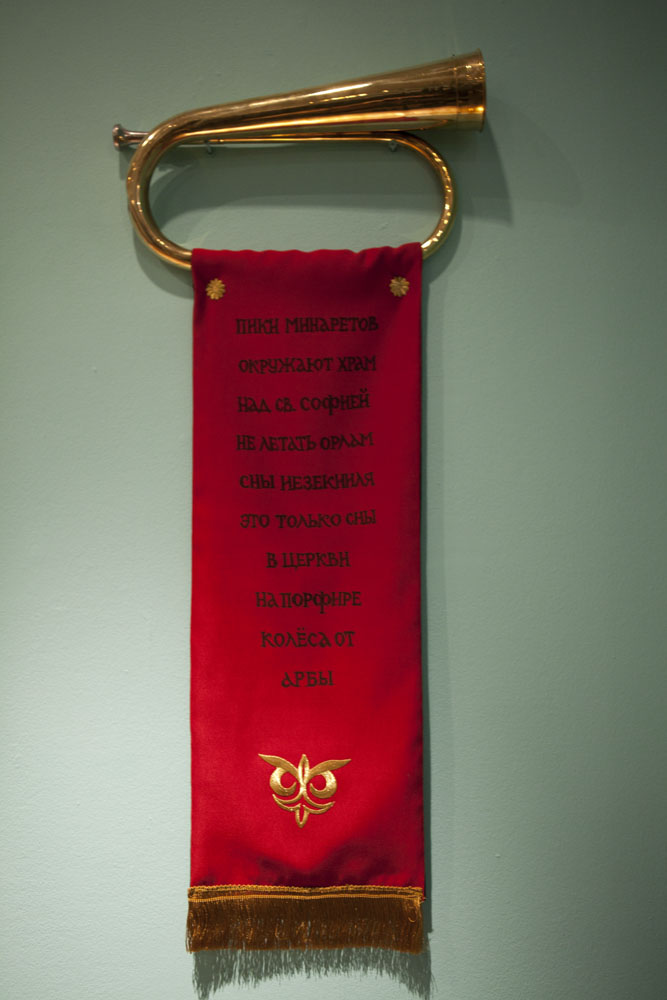

There are two key sources of Filippov’s aesthetics: Soviet reality which he ironically dissects(although he claims it is not a critique nor satire) andChristian imagery and mythology of the State taken from Byzantine and pre-Revolutionary Russia. So one can find double-headed eagles, hammers and sickles, Kremlin wall, Soviet propaganda mass media, cathedral’s architecture, angelic wings, Doomsday’s trumpets, references to Evangelic legends and classical Russian literature in the artist’s installations. There are also several references to some cultural key figures like J. D. Salinger, Dino Buzzati and Marcel Broodthaers but they are not so central – Filippov is very contextual and his context, first and foremost, is the “Russian spiritual culture” in the XIX century. This makes the artist very old-school in terms of the ideological background of his works.

Like artworks of Vadim Zakharov, Andrey Monastyrsky and some other late conceptual artists from the Moscow art community, installations of Filippov are very “cold” and emotionally mute but, unlike Zakharov and Co., they are not so rationally grounded. Maybe Filipov’s religious views play a role here. Formally his pieces are very close to design but in the work of Filippov there is always a gap between pure beauty, interior decoration and artistic narrative. Also, unlike postmodernism or Russian/Eurasian/Soviet/Orthodox civilization envisioned in art and literature from the1990s and 2000s (novels of Pavel Krusanov, Vladimir Sorokin and Victor Pelevin, artworks by Timur Novikov, Laboratory of Frozen Subsoil, Boris Orlov, Pepperstein, Elagina and Makarevich, Slavs and Tatars), Andrey Filippov is not ready to mix and match all sorts of images with one another. His exploitation of these topics has its limits. And unlike far-Right artists working on the same topics (think of Belayev-Gintovt for instance), Filippov is not so obsessed with the ideas behind this imagery. He is personally independent from that dangerous background. Born in 1959, Filippov is a mild conservative, just as the majority of his generation.

Last year when the Kandinsky Prize went to Pavel Pepperstein, among the responses to the jury’s choice was an article by Sophia Kishkovsky in The Art Newspaper titled “Kandinsky Prize winner supported Russia’s annexation of Crimea”. The author wrote that the Moscow artist who had spent “most of the past 15 years living in Crimea” considered the annexation of the peninsula by Russia a good deed because it helped to prevent “a bloodbath and numerous deaths” and that the population of Crimea had “dreamed of coming back to Russia”. All these things were said in an interview “published… just two weeks after President Vladimir Putin formalised the annexation [of Crimea] at a ceremony in the Kremlin”. With the publication of that review it became clear that from this moment on every artist awarded this major Russian prize would be attentively monitored for his or her views on Crimea, war in Eastern Ukraine and so on.

So the fact that Filippov’s installation The Wheel in the Head which won him the prize, includes references to Crimea will alert critics. The artwork exists of two central objects: a spinning “wheel, which is both a Buddhist prayer wheel and the corona lucis at an Orthodox church on Mount Athos”, as the artist explains, and the working place of a naval officer including a map of Crimea, a WWII German machine gun and a Turkish fez adorned with a Russian cap badge, all of them referencing different historical layers and tragic collisions. In the periphery of the installation we find trumpets of the Apocalypse, engravings of “Holy Russia”, a Cubist-like portrait of a flag and badges with the imperial eagle on them.

What is the artists position here one has to ask? Filippov said that he is indifferent to our current times but is quite critical of the 1990s. The artist also added that his father, a sailor, “experienced very badly all that happened to Crimea in post-Soviet times,” with which he means its status as part of Ukraine. Filippov concluded that “the return of Crimea was a kind of rehabilitation.” I think this is the most common attitude to Crimea’s annexation in Russia – non-exultant and non-agressive, but rather a silent and sometimes fatalistic agreement with the will of those who rule.

Time will tell how this consensus will be questioned but for now we can see that this state of mind is dominant, the choices made by the Kandinsky Prize’s jury has confirmed this yet again.

Sergey Guskov