Bik Van der Pol x Charlemagne Palestine

Opening tonight at Witte de With: Charlemagne Palestine. Bik Van der Pol went to Brussels to talk with the artist about work and life, Wies Smals an her dramatic plane crash, teddy bears and his amazing residence: Palais Stoclet.

You performed in the early days of de Appel?

Yes, from the very first two years, I think. With Wies Smals and then at a certain moment, she collaborated with Josine van Droffelaar, who was assistant curator at the Stedelijk in those days. I’m happy to, sort of, be the Uncle Appel.

Uncle Appel. The last one standing.

I was a pilot in those days.

You mean a pilot, flying?

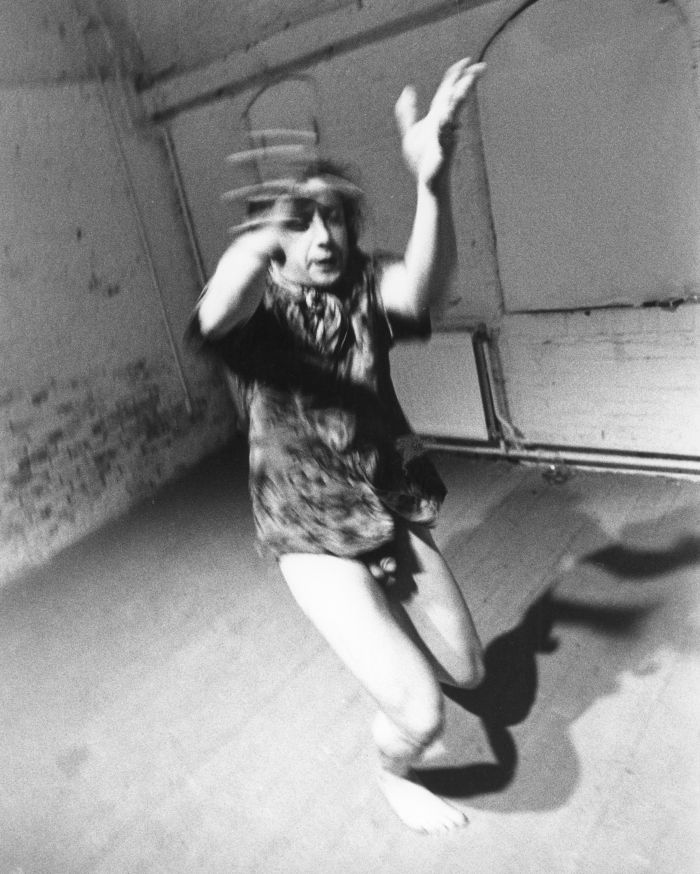

What happened is that I went to live for a year, almost a year, in Sweden, in Skåne which is down below Stockholm. It’s, sort of, big countryside and of Danish origin. The Danes used to be there in the Middle Ages. And I met a collector of art. I had a few shows of these drawings I was doing in those days with all kinds of arrows that went in all kinds of directions. I was just dealing with directions, because I was doing body pieces where I would run into a wall and then another one. It was all about motion. So I met a collector who wanted to buy an enormous drawing. I told him the price. And he said, ‘Well, wouldn’t you like to be a pilot?’ I said, ‘What?’ ‘Well I have an airplane and a helicopter and I’m an official instructor. What if I gave you lessons, got you your licence and gave you the possibility to fly planes and helicopters? Would you then give one of these big drawings for free?’ So I said, ‘Okay’, and I became a pilot. The boyfriend Martin of Josine van Droffelaar, who at that time was the assistant director of de Appel, was a pilot too.

Martin was in my class at art school in Rotterdam. We called him ‘Martin Air’.

That’s him. Yes, I knew Martin. We used to fly together.

He went to Switzerland I think?

That’s right. In Bern. I was there. I was there the day they came, the night before. They came for an opening of a show at the Kunsthalle of Larry Weiner and Regalia in the Lake of Daniel Buren. They were filming in fact the Daniel Buren, from their airplane. It was a very heavy World War II airplane, not like the kind of airplanes that people fly now. I think they rented it. It was a small plane, a four seater, a propeller plane. That’s how we all got together as a, sort of, bunch of pilots. We didn’t do so much flying together, because it’s very expensive. So you had to plan carefully, as a group. Say you leave at 7:00 in the morning and you bring the plane back at 5:00, otherwise you pay an enormous amount. You have to have a flight plan. It’s very complicated, but it was fun. Well it was fun until they died. They all died in that plane crash. I said goodbye to them, to Wies, who at that time was with Von Graevenitz. They had a son, little Heinrich. I gave him a teddy bear. A new, fantastic, Steiff teddy bear.’

He was in the plane too?

Yes, he was three months old. As was Von Graevenitz, Wies, Josine and Martin. That’s it. That was it.

Martin was flying?

Well Martin and Josine, I suppose. They flew to Bern from Amsterdam. Then the next morning they decided, at breakfast, that they would not go straight back, but take a little detour through the Swiss Alps. As one knows now in hindsight that wasn’t a very good idea. They had never had any important experience flying in the mountains, with its thermal changes which create sometimes very violent differences in air pressure. They were very arrogant-, even the woman I was with back then said to Wies, ‘Aren’t you scared to go in an airplane with this new baby?’ ‘Oh, no, no, no’, she said. I remember the whole conversation. Wies was always a very tough woman and now she was going to be a mother and she was a tough mother as well and several hours later, they were all dead.’

We called him Martin Air, because it was a flight company at the time. But also, Martin Air, you know, ‘air’, is a little bit arrogant. It had this double meaning.

They were all a little bit arrogant. Anyway, Wies had invited me very, very early in ’73 already. There is a video that we did together that she hated. This tape actually is a dialogue between me and Wies Smals that goes on for 45 minutes. She’s filming me and in one part I start to get more and more aggressive with her and then I take the camera out of her hands and I turn it and you see her and she’s like this, looking right into the camera. It’s one of the only times that she was filmed, because even though she was into performance, she herself was very camera shy. She didn’t like to be in front of the camera. Yet she ran this art centre for all these narcissists which worked perfectly. There was no competition between her and the performers, because she didn’t want to be one.

What did you talk about?

About my work. It’s fabulous. You really should get to see it. She was great and you’ll see what she really looked like. It’s called ‘Where It’s Coming From’, and until her death, nobody saw it. Only last year, we did a whole evening at Electronic Arts Intermix, during my blitz in New York with The Whitney, with MoMA, with Sonnabend… I was everywhere. And we showed the film.

We showed the film you made with Leo Castelli then and Richard Serra at the Boijmans. When was this film made?

I’ll tell you a funny story. I spoke about that film to Joan Jonas and many different people. Long before the Boijmans, before you guys wrote me that you saw this film, and I was shocked, because I was looking for this film for a long long time. Everybody thought I’d made up this story, of making this film. They did not believe me because I was in a bad mood at the time. They said, ‘Charlemagne is having delusions.’ I said, ‘You know, there’s this damn film that Richard Serra made of me and then it disappeared.’ So I was having all these disappearance stories, but these stories are really true. All the films they did with me and they hated afterwards have disappeared. It just happened to be like that and now they’re being revived.

In this case it was a 16 mm film that I had done with Nancy Holt. So I was trying to get Nancy Holt, who was the widow of Robert Smithson and then you guys showed up with it. It turned out that when it first came out, Richard Serra who was quite well known as a video and film artist those days in those days, did the scene. At that time, around ‘74 Holland was really hot on New York performance art and media art. So very early the Boijmans bought that film from Leo Castelli, who then had just opened. There were so many artists of their group who were doing film and video, Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend decided: why not open up a small office and get some equipment? They had enough high-paid artists to afford to have a stock of Portapaks and somebody at a desk and Richard Rauschenberg and a lot of their high-selling artists were interested in this stuff. It was not until the late ‘70s, that the Castelli-Sonnabend video company eventually closed and they gave everything to EAI.

So how did this piece disappear?

Richard and I were friends for a few minutes and during those few minutes he decided, ‘Why not have Charlemagne because he’s so confrontative and things like that.’ Actually at that particular moment, he liked that and he himself is very confrontative person. I mean, his works are, like (bangs something), but he himself, he’s a monster. So when the space opened, Richard had placed the piece right near Leo’s office. In the piece I do a lot of, ‘Ha, ha, ho, ho,’ and I make all this noise and after the first week, Leo went bananas. He couldn’t stand my voice anymore so they put the sound lower and lower. And once I had disappeared from their scene, they decided the piece didn’t exist anymore either. But before they could ‘nix’ that film, the Boijmans and several other places had already bought it and so through you I found out that there was an actual copy.

What was the film about?

Like a lot of Richard Serra’s work too, it was an enormous thing about nothing. I’m only joking, Richard, if ever this is in our interview….

You know that a film two years ago with Nancy Holt, about Robert Smithson’s sculpture in Drenthe

Yes. What was the name of that organisation? I used to know all those guys in the early ‘70s? That organisation that invited Robert Morris to do that piece?

Kröller-Müller?

Yes, that’s it.

I think the Smithson sculpture was made during the Sonsbeek exhibition in the ‘70s.

I was involved with that, because I did a lot of running pieces in those days, outdoors too, like the Island Song. I always thought of myself as the Minotaur in those kinds of sculptural environments. There were all these pieces and people would come in and they would sort of look. In the piece of Robert Morris [Observatorium, 1971], you get to the middle and there’s a certain place in the middle and if you make the sound, it all of a sudden resonates. So people come, and the Dutch, they’re very polite. So I’m like the gorilla. You can see where sonically and bodily Morris’ piece is, with a Minotaur in your piece.

You had a lot of fun with Nancy, apparently. No?

Yes, we had a lot of fun. I was that kind of guy. Everybody there was so seriously. I was always the clown and they were very open to clown with me, and that is good because it wasn’t so funny otherwise. I was someone to have around if you were getting bored with being serious and I would come and certainly I would break the seriousness, because I’m allergic to being too serious. Aude says, ‘But you know you’re very serious in your way.’ I’m very serious in my way, but I don’t like official or superficial seriousness. That, I’m allergic to. So when things need to be serious, I am. I don’t laugh at funerals. I’m really good. I’m like Francois Hollande. He’s great at funerals and at memorials. Better than he is at every day, he just has the right look. You need to have a good look for funerals.

Are we still going to see the palace, here in Brussels?

Maybe we’ll go to the Palais [Palais Stoclet] first. There are two enormous Gustav Klimts in there, not flat paintings, but mosaics. Klimt did two mosaics and these are only two. He went to Ravenna, in Italy, in the early 1901, 1902. Aude’s grandparents commissioned Klimt to do these two enormous mosaics and a smaller one. Each mosaic is about the size of this room, on either side. You’ll see it, it’s in the dining room. The building was built by Joseph Hoffmann, the most important Art Nouveau architect of his time. This palace is considered his great masterpiece. The idea, in those days, which was from art and-,

Art and crafts?

I’m a Gesamtkunstler, a total artist, but the actual term used historically came at the time of Art Nouveau, with architects. As the idea that their buildings then and the building that Aude’s grandparents built, is the only intact example of a Gesamtkunstwerk Art Nouveau in the world and it’s the most luxurious one, because Aude’s great-grandfather helped build all the railroads in Europe and Aude’s grandfather was living in Vienna with his new wife, Stevens who came from a family of artists. Aude, lived there from when she was twelve until she was about 24. Then she married Flagier who recently died. And where she was born, now lives Herman Daled who founded Wiels. He’s a famous collector of conceptual art. He was a radiologist. We now want to make the Palais a cultural heritage site from where nobody can take anything. Ronald Lauder, the descendent of the two sons of the Estée Lauder fortune, wanted to buy the Palais just like that, about six, seven years ago for $100 million dollars. But he couldn’t. It turned out, around the same month that he wanted to buy the whole building, one little painting, which wasn’t a part of the ‘Gesamtkunstwerk’ was a painting by Duccio, an Italian from the fourteenth century. This was sold to the Metropolitan Museum for $52 million Dollars. By the family, the four sisters, of which Aude is one. Aude inherited one quarter of that, she gave half of it to her son, and we found this fantastic space. So she also paid for my studio.

Do you like Brussels?

Yes. I mean, New York isn’t what it was, so I don’t feel-, I mean, I miss my sandwiches but that’s about it. I don’t really miss the New York that it’s become now. In Brooklyn, there were maybe 30 artists when I was a young kid, now there are 60,000. So, I mean, I don’t feel any connection anymore with any town. We go to so many different towns, but Brussels is a nice place to come back to, I mean, it’s perfect. I’ve even chosen my cemetery here. It’s next to the theatre. Broodthaers is already there, but I don’t like his neighbourhood, I’ve chosen another neighbourhood, right near the exit of the cemetery. The cemetery in New York that I have the right to be in, Jewish, is a wonderful cemetery, but it’s one hour and ten minutes from New York City. When you leave the cemetery, there’s not even a place to have a coffee. But here, there are at least fifteen restaurants and twenty bars when you go out the door. There are always people all the time, making noise, drinking, eating, sexy people and everything. I love it. So that’s where I want to be.

This is Aude’s grandfather’s house. This is the palace Stoclet

My God. It’s crazy, yes.

It was built between 1905 and 1912.

When you were in Documenta was that with Harold Szeeman or was it the one before or after?

I was in three Documentas, but the only one that really counted was the last one, 1987, hen I built my big Godbear with three heads, six metres high in mohair. It was the same year that Andy Warhol and Joseph Beuys died. They decided that the Documenta now would have a real performance and installation part. In 1987. The piece was in a park, and then eventually in a road. We disputed. Manfred Schneckenburger, the artistic director, and me. Everybody wanted it in front of the Fredericianum and we had a terrible dispute over the whole summer. In those days, there was a woman called Elizabeth Yappe who came from Cologne. She had a performance gallery in Cologne during the ‘80s that was quite well-known. So she was named as the performance and installation curator of Documenta under Manfred Schneckenburger. She loved my work and she asked me to do a piece, thinking that I would come with a performance, but I had already planned for about three or four years, with Steiff-, the company which also is not so far from Kassel, in Germany, they had invented the teddy bear, after the Jewish couple from Brooklyn invented it, where I was born, in that neighbourhood. I got to know the head designer, who was the great nephew of Margarete Steiff, the woman with polio that invented the teddy bear in Germany.

How big was the bear?

Six metres high. It’s in that catalogue. Now I’m starting to rebuild them in smaller versions and they’re getting bigger and bigger again. But now they’re standing and they used to be sitting. Schneckenburger found it the worst piece he had ever imagined. Thanks to ZDF, who filmed it at the opening, the bear became the mascotte of the Documenta 8. It made Schneckenburger furious, because for the whole summer, whenever they would show what’s happening at Documenta, the bear was there like a logo. It was in the newspapers every few days. The most important piece of that particular Documenta was Walter De Maria’s One Kilometre. And so what did you expect the helicopters and the television to look at?

What happened to the bear afterwards?

Afterwards, my gallery went bankrupt and then -it was stored in Germany in one of the most prestigious art storage places near Düsseldorf- it mysteriously burned.

Burned? It wasn’t insured?

Whatever capital came into the gallery went immediately to pay off the liquidation of the bankruptcy of the gallery, so I got nothing. I just got a telephone call saying, ‘Your bear is destroyed.’ I was leaving works there without any paperwork, in Geneva. One day, the gallery closes and all my works I have no provenance, nothing that proves that they’re mine. Nothing that proves that they were still mine. So the liquidators came and took all the gallery apart because it was in debt for about 10 million. Not only mine, but a whole bunch of works became prisoners in a PricewaterHouse Coopers liquidation of the situation. From 1993, 1992 to 2000, it was owned by the liquidator purchaser, which is a guy goes to liquidations. Sort of a hedge fund, and Pricewaterhouse was a very famous one. I was eventually able to buy my own works back for about $30,000. All of my works. I mean, $30,000 was a lot to ask Aude. For an artist of my pedigree, it was nothing. So, you know, we finally bought all my works back. He sent it, even, with a truck, he was very correct. We got all the works back, except some of my works, that his former Brazilian girlfriend had stolen: one of my very important works, and we don’t know whatever happened to that work yet. It’s still out there somewhere.

GesammttkkunnsttMeshuggahhLaandtttt by Charlemagne Palestine

Witte de With, Rotterdam

28.1 t/m 1.5.2016

THIS TEXT WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN METROPOLIS M N0 3-2015