Collections in Transition, Users in Position

While working on a review on the quite dense conference Collections in Transition: Decolonising, Demodernising and Decentralising?, I feel modest and humble. I attended one day of the two-day event, which also included presentations of ‘deviant art practices’, all of this in the framework of the L’Internationale collaboration of six European art institutions, and the opening of a new collection display at the Van Abbe Museum.[1] No resume could do justice to the twenty (!) presentations and lectures that I attended, and the quick tour through the museum displays. Not less important, as the white male art historian who seems to be the target of the dignified task to decolonise, I should probably be the last one to criticise that task.

To start, my feelings of humbleness were aptly accommodated by the first keynote by Rolando Vázquez, assistant professor of Sociology at University College Roosevelt of Utrecht University and coordinator of the Decolonial Summer School Middelburg. With a convenient 30-minute talk on decolonisation for museum curators, his brilliant summarisation of otherwise quite complex writings served the audience well. Vázquez echoed Argentine semiotician Walter Mignolo’s proposition that we should understand modernity as the mirror side of colonialism. Driven by relentless accumulation of capital, colonialism was the tool for appropriation and exploitation of land and their inhabitants. It negated ‘the other’, and worse, it also erased that negation through its understanding of the world. The enlightened distinction between nature and culture, between human and object, for instance, is part of that erasure. Parsing a geographically comprehended worldview with the idea of progress is typical of modernity’s episteme, through which the other is always seen as ‘lagging behind’. And so the centre defines itself as the centre. The term ‘contemporary’ in contemporary art is pitted against subjects deemed ‘not contemporary’ and used as an a priori qualification. According to Vázquez, one decolonial option could be to recognise this centred implicatedness, and start listening to the other.

Driven by relentless accumulation of capital, colonialism was the tool for appropriation and exploitation of land and their inhabitants. It negated ‘the other’, and worse, it also erased that negation through its understanding of the world

Although colonialism consists of unhampered accumulation, appropriation and negation, modernity might entail a little more than just that. Art critic, historian and curator Geeta Kapur responded to a discussion on social media started by Van Abbe director Charles Esche, in which he pleas for ‘demodernising’. Countering Esche, Kapur situated Western modernity as a welcome frame of reference when speaking from the perspective of India. Yes, India has been subjected to colonial violence. Yes, that violent imposition of modernity forced India to think of alternatives on its way to independence. Ghandi for example, with his non-violent resistance, was notoriously anti-modern and heralded Indian village life. On the other hand, while current Prime Minister Narendra Modi slowly steers India into the darker resorts of Hindu nationalism, Western modernity could actually serve as a policing example to refrain from real violence (against Muslims and Sikhs). After all, modernity does allow for antagonism and contestation between populations in the political arena. Kapur’s message was basically not to give up on modernity just yet. However, she continued, if we feel a need to ‘demodernise’ in some way or another, we had better use scholar and artist Svetlana Boym’s notion of the ‘off-modern’: to be able to put modernity between brackets, cherish its errors, embrace amateurism, and simply not be greedy.

Such intellectual highlights were a necessary compensation for the inherent contradictions that were looming over the conference while it progressed. A problem was the heavy accent on institutional presenters who almost all tended towards promoting their respective dignified projects. Vázquez’ recommendation to listen seemed to be solely directed to the audience, since the dense program allowed neither time nor opportunity for feedback. I myself attended a panel that was to discuss the ‘constituencies’ of the museum. Interesting indeed, but after its five introductory presentations there was no time left to actually address that burning issue.

A reoccurring topic during the symposium and in the collection displays was the reconsideration of the use of art. At the Van Abbe, this notion has resulted in exiting narratives in which the focus is no longer on the autonomy of the artworks, but on their socio-historical contexts. The most radical display in this respect is The Making of Modern Art on the ground floor. In it, the history of art is conceived as through the eyes of a distant observer, an anthropologist, who does not look at the artwork per se, but at the social system in which art could become a core subject. The exhibit features the mixing of artworks from the collection with reproductions of them, with reproductions of masterpieces and of their displays throughout the centuries, and, subversively from a museum viewpoint, copies that cannot be distinguished from the original paintings in the collection. A brilliant and daring display that, like the presentations at the conference, radiates the message that the days of art as tangible, autonomous (and accumulated) objects are long gone.

A brilliant and daring display that, like the presentations at the conference, radiates the message that the days of art as tangible, autonomous (and accumulated) objects are long gone

But is that ‘demodern’? The Making of Modern Art, convened by the Museum of American Art (which is a one-person enterprise), can indeed not be understood through modernism as it has watered down in the museum after the Second World War. But it would be completely incomprehensible without the radical, iconoclastic, anti-bourgeois modernism from the era of Walter Benjamin and before. It is not so much the usership that changes, but the focus. The figure of the refugee, for instance, seems to have become as much a fetish for European politicians as for European art institutions. But that does not make him or her a necessary part of museum practices, something that would indeed be in the interest of a truly decolonising perspective, in which minorities can find an arena to speak up.

Inevitably, a long day of talks paved the way for a more unclenched, even relaxed atmosphere at the concluding session of the conference. Finally, the floor was for the padres of the museums. They visibly felt at ease at the Van Abbe. This natural habitat forced some of them to abuse the microphone for pitching their institutional projects. But Ferran Barenblit, the new director of the MACBA (a L’Internationale collaborator) retained his role of the humble listener. Prompted by Vázquez’ incentive he questioned the financial colonisation of the museum in the neo-liberal era. He suggested that the museum should rather think in terms of moral progress, and no longer in terms of budget growth. His gentle effort to attune to the decolonising atmosphere set at the beginning of the day was quickly degraded by his colleague Bart De Baere, who took the time to promote the current expansion of the M HKA building in Antwerp. One wonders why and how these two rigidly opposing viewpoints are to be brought together in the L’Internationale complex if it was not for the sheer opportunity of budget expansion by EU subsidy.

The few propositions from the audience for discussion concerning the internal tensions and fears, and the alarming lack of even demographical representation within institutions were quickly sidestepped. During one of the panel discussions, Mirjam Shatanawi of the Dutch National Museum of World Cultures in all modesty tried to question the absence of ethnographic objects in modern art museum collection displays, which could be taken as a critique of the perpetual negation of religion in modern (and demodern) contexts. But also that inducement to discuss a real subject was effectively smothered in the cheerful paternalistic bravura of the event.

But also that inducement to discuss a real subject was effectively smothered in the cheerful paternalistic bravura of the event

Although the public expected fireworks from constituent representatives capable of intellectual exchange at a certain level, the room got filled with elephants of the institutional kind instead. And so a long day that began with a sincere aim to decolonise ended in its reverse, in a recolonization: of space, time and the audience.

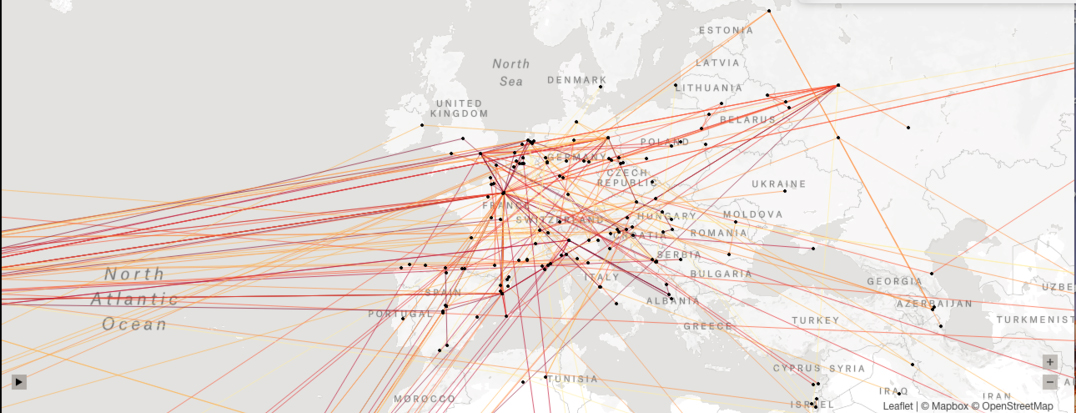

[1] L’Internationale brings together six major European art institutions: Moderna galerija (MG+MSUM, Ljubljana, Slovenia); Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (MNCARS, Madrid, Spain); Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA, Barcelona, Spain); Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen (M HKA, Antwerp, Belgium); SALT (Istanbul and Ankara, Turkey) and Van Abbemuseum (VAM, Eindhoven, the Netherlands).

Symposium Collections in Transition: Decolonising, Demodernising and Decentralising? Van Abbe Museum, 22.09.2017.

lead image: Map from the project “Mapping Collections” by L’Internationale. See more, HERE!

Jelle Bouwhuis

PhD researcher Modern and Contemporary Art Museums, Globalization and Diversity, VU Amsterdam