Intimacy – interview Bruno Zhu

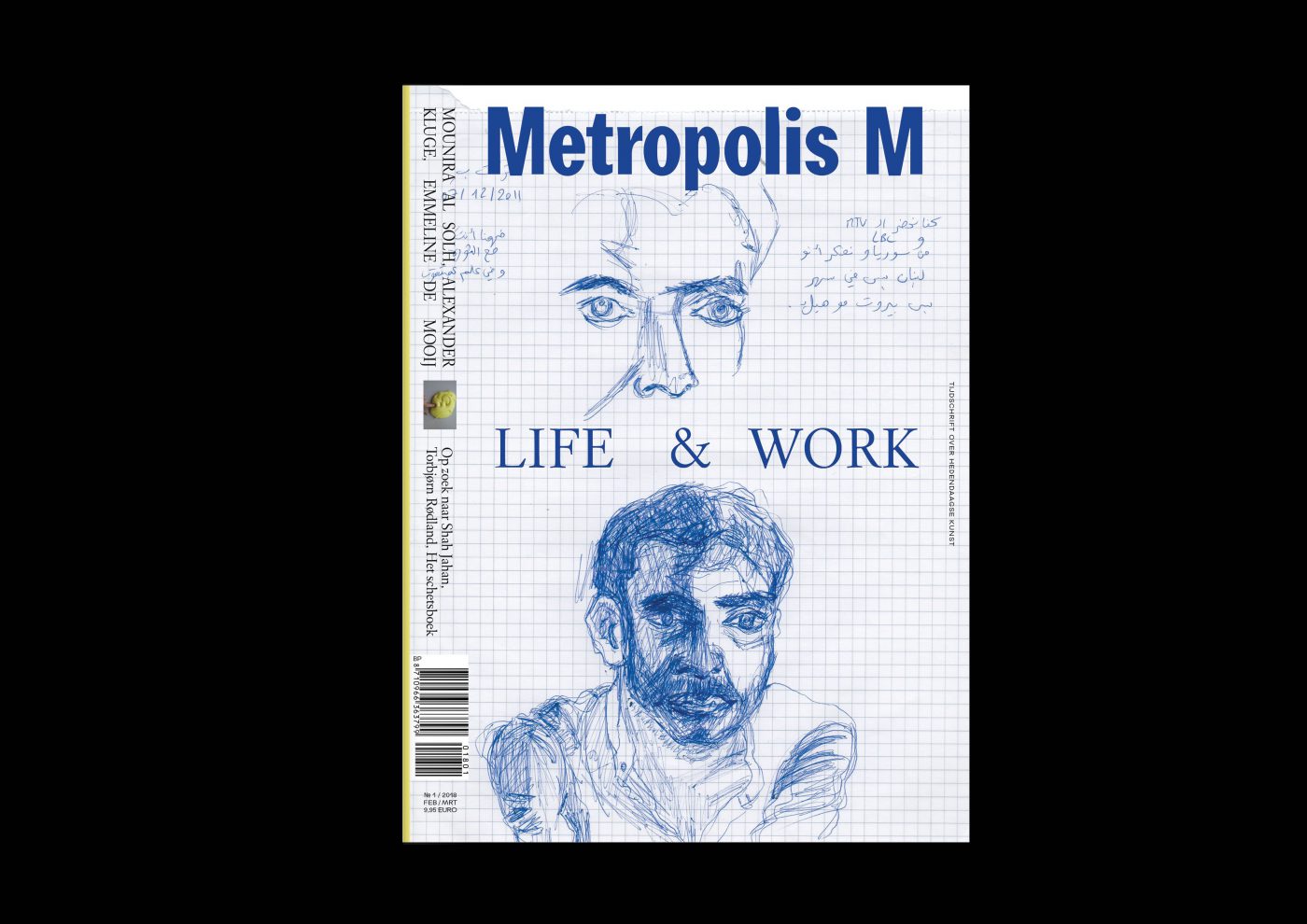

The Life & Work issue of Metropolis M features Bruno Zhu, under the umbrella of A Maior. Domeniek Ruyters talks to him about his curatorial projects in reference to his current solo show at the Kunsthalle Lissabon.

Domeniek Ruyters: Could you tell us something about A Maior?

Bruno Zhu: A Maior is a clothing and home furnishing store located in Viseu, Portugal. We opened roughly eight years ago, taking over a standalone U-shaped warehouse that used to be a car dealership. It is largely managed by my father, with some feedback from my mother who runs our other shop Chao Sheng, with four to five staff members. We sell a wide range of products from personal hygiene to kitchen utensils, gardening, electric supplies, cosmetics, clothing, footwear, home textiles, toys, stationery and so on, except food. We are neighbours to the Chinese all-you-can eat buffet Wok T and a family-owned petrol station, somehow turning the complex into a fuller shopping and food ‘to go’ experience. In late 2016, we initiated an eponymous curatorial program inside the shop that navigates the daily happenings of the commercial environment. In Portuguese, ’a maior’ means ‘the biggest’ or ‘the greatest’ depending on the context.

DR: What else does the project include? Which former activities, planned activities?

BZ: The curatorial program is currently composed of solo and group exhibitions. The individual exhibitions result from a long-term dialogue with each artist, thinking through and alongside the limitations that the shopping environment offers. How to engage with an ecosystem that will inevitably overpower the presence of a work of art and its creator? And if the work of art is undressed of its aura and author, what does it become, what is left of it? We have hosted presentations by Eloísa Ejarque and Tiago de Sá, Lucy Chinen, LIFE SPORT, Dan Walwin, Diana Carvalho and currently Krista Mary Martin. The group exhibitions respond to similar concerns, albeit with a bias towards fiction as a methodology. Perhaps I am misusing ‘fiction’ here, but imagining A Maior as a site beyond the ‘shop’ that it is, beyond the ‘art shows’ that it hosts, has allowed us to connect subjects that otherwise wouldn’t sit in the same plane. We have organised a fashion photography exhibition (‘Veronica’); a show across the windows (‘Cilada’) featuring Claire Fontaine, the French stationery brand, Zara TRF t-shirts and original artworks by Yanyan Huang and Charlott Weise; a backstage photoshoot (‘Roupas’) of my grandmother being styled by my mother with clothing we sell; and a Christmas tree show (‘Árvores das Patacas’) with trees decorated by each staff member. Future presentations include a solo exhibition by Josip Novosel and temporarily hosting Chris Airlines, an upcoming Berlin-based curatorial project. We are already sketching this year Christmas show, which involves cookie jars inspired by Khloe Kardashian’s ‘KHLO-C-D’ tips.

DR: Why did you start this in-shop curatorial project?

BZ: The project came as a natural progression from a collaboration with my mother. In 2015, I invited her to curate my first solo exhibition in Portugal, where she utilised my work to engage with the gallery space as if it was a domestic space. My mother was tasked to browse through sculptural collages made of IKEA cabinets leftovers and large scale stickers of furniture, and compose them in relation to a series of chicken wire sculptures with a print of my sister’s face, given shape by a hug. Through shared agency, my mother became simultaneously a curator of an art exhibition and a curator of a household. It made evident to me how urgent the intimacy involved in the act of decorating was, to place an object in reference to another in order to invite immediate affection, familiarity and desire. I think curating could learn from the warmth of decorating. It was very important for my mother to ‘please’ me, but I was very eager to ‘please’ her since it was her vision that was truly on display. A year later, I thought we could continue this collaborative curating in her domain, at one of her shops, where she spends most of her days figuring out ways to display products, so they get sold faster.

[blockquote]We believe that the shopper’s gaze is both highly acute and disarmed towards surface

DR: Critical does not seem the right word for these curatorial projects. How would you like to describe what they imply?

BZ: To be honest, I wouldn’t know how to label our activity as of now. I definitely do not think the work we do is critical in any way to and of the various art codes we have been exploring. I don’t consider the project to be ironic about what and where it is shown, nor is it cynical towards its primary audience which are our frequent customers. We are curious in placing abstract subjects next to the seemingly familiar — perhaps seeing it as a pseudo-downgrading of an artwork’s symbolic value — as a proposal for an aesthetic sensibility that could exist outside the high/low culture binary. We believe that the shopper’s gaze is both highly acute and disarmed towards surface, which translates into primary needs such as: is this pretty/ugly, does this go well with the other thing, does this come in a bigger/smaller size, etc. They are simple questions that cover complex networks of feeling in private spaces. I think tapping into this frequency of cognition would allow us to unpack material that analytical discourse can only do with coldness and distance. A Maior is not offering a solution, but if one can ‘learn-by-doing’, then we would like to propose ‘learning-by-placing’: allowing uncanny placements/displacements, absurdist associations and blunt encounters.

A few months ago, my mother asked what the shop project meant to me. I tried to explain how it suggested a political project born out of a consumerist language — if one consumes therefore one becomes — but she was confused because for her “political” is for politicians and the shop is not a government. It took me a while to explain how she kind of got my point, because a politics implies an awareness of power dynamics, but she was then even more confused, because “power” for her meant physical strength. And again, I tried to tell how she was not far from what I was trying to explain, so we arrived at “performance”, and she told me that she once heard “life is a theatre” and I agreed. The point is not trying to discern what is real from fiction, but to recognise everyday performance as a production of new beginnings.

Clothes have the power to make us memorable or forgettable

DR: The images in Metropolis M present a kind of fashion shoot. How important are clothes to you?

BZ: Large part of my formative years was spent with clothes, because I studied fashion design. My interest in clothing was largely cultivated by a “brand mania” that still exists at home. For my parents, it was always about buying the newest Nokia mobile phone, the newest Omega watch, the wide range of Paul Shark polo shirts for my father, and a Swarovski membership for my mother. I think this was common between my parents’ friends too. They enjoyed displaying their riches for each other, they still do, and if one had bought something, the others would follow. Fashion, or what is fashionable, was shown to me as currency, something to attain access with. Fashion school was great because it taught us how to deconstruct our perception of luxury goods, so it became clearer to me why I was attracted to the fashion system. I appreciate design and craftsmanship, but it’s the attribution of value that I find the most exciting. Exciting in the sense that it is purely speculative and complicit with a tortured understanding of “originality”. To be “original” is to provide a high-impact visual, being able to glide through the contemporary in order to exist both in the past and in the future. Clothes have the power to make us memorable or forgettable.

DR: In other recent work you work a lot with mannequins, like at Art Rotterdam, and also in your current show at the Kunsthalle Lissabon. The clothing however does not seem to be important as such. Or am I mistaken?

BZ: I wouldn’t separate clothing from how it is displayed, and in these two instances, the styling was heavily context-specific. For Art Rotterdam, the project space La Plage and I went to several second hand clothing stores and shopped together, discussing and styling looks on the spot. It transformed the commission into a collective sculpture, where who invites and the invited become immensely implicated in the creative process. As a group, we crafted several characters thinking about the bourgeoisie and the arty class arriving, leaving or lost at the fairgrounds in the icy evenings of February. In Kunsthalle Lissabon, the “presence” mirrors a formal pattern of flatness and deflation carried through the other objects in the exhibition. The clothing is oversized allowing for volumes that allude to a body shape that is not defined; the look is finished with a pair of men’s trousers turned long gloves, decorated with nails by JUNZIOUI. It was important to express a grotesque elegance, something angry, but held back; the figure flaunts its loneliness and wants to cast that moody shadow to anyone looking at it. Clothing as vocabulary gives me freedom to drag and cross various symbols to manipulate several histories. I would say its methodology is very simple and brutal: you put on, you undress, you try something else, you match, you mix. In all these iterations, we become something while facing the mirror and facing others: we pose, we pretend, we seduce and we conceal.

DR: What can you say about the mannequins? Why did you start to work with them, their clothing, sculptural attitude and function? They also seem to express a certain existential mood.

BZ: To put it bluntly, I was wondering how it would look like if I started to populate the images I have been creating in the past few years. How would these persons feel, what origins could be attributed to them, when would they cease to be in hiding? On a formal level, I was interested in arriving at a situation where images read largely as affective constructions. By that I mean focusing on how we remember images rather than on their plastic qualities and how that is manipulated. I found a vessel in mannequins, since they are a simulacrum of our bodies, and by bending their highly gendered physiques via styling exercises, I wanted to arrive at an unusual, off-kilter beat. The process became one of handling layers or skins be it clothing, accessories, masks, hair. But the most tricky layer/skin of them all is their animation; by that I mean to imbue a “life” in them. In both moments mentioned above, I became a ‘living statue’ throughout the installations. At Art Rotterdam, a fourth mannequin would occasionally join the others. In Kunsthalle Lissabon, the figure was a living statue at the opening night, and remained “waiting” during the exhibition period. The living statue trope exposes an ambiguous economy of control. The statue stays still, like an image until we throw a coin at it, and when we do, it moves. It moves as a result of us paying for such movement, as if we activated something, but do we control the movement itself, or does the performer seduce us in thinking so? I think this brings us to your existential mood observation.

DR: In Lisbon the show mixes a shopping experience into something cultural or artistic. A motive you turn back to more often. Could you explain what this mix implies for art (and consumerism) and why this mix is so effective for you?

BZ: In the landscape I am putting forth through my practice, a shopping experience is a cultural and artistic event, and I am not implying anything: art simply belongs to a consumer narrative. I’m not being ironic nor sarcastic. It might come across as frivolous to some, but I can confidently say that engaging with works of art as if they were pretty teacups, has helped me center my critical voice and my personal politics. Otherwise, how would we justify the rituals of experiencing art: from contributing foot traffic to galleries, museums, project spaces; passing by everyday graphics showing zeitgeist aspirations; choosing what culturally significant events to attend and be seen at; choosing to go to an art academy to ‘learn’ about art. In all these cases, the individual chooses what information to receive and consumes it in order to assimilate it; not to mention the several capitals these choices feed in the process. I don’t believe there is a higher moral ground that only art or the art connoisseur unlocks. Like the other industries of life, art has its own hierarchies of knowledge, which require a trained sensibility to navigate through. And that’s really it, or at least I believe it to be. In levelling artistic production with the other productions of life, we clear a channel for art to be registered with an emotional edge that art history does not allow. I do believe that going shopping at Zara, followed by a period sitting in a café thinking what to cook for dinner is a parallel experience and of equal importance to spending an afternoon with modernist sculptures. In both scenarios, we never stop thinking about our intentions: what we were aspiring to while going into these experiences, and what we get out of them. I think there is a very generous sincerity to this, and contemporary art is in dire need for some straightforward sincerity.

DR: What is the installation in Lisbon about?

BZ: I would like to redirect you to an interview I did with the Kunsthalle Lissabon last Fall for Cura. It is a preview of the space, so it highlights several works that are on show. I speak about the unease I felt when invited to show at a “home” that doesn’t recognise me as one of their own. The only aspect I didn’t mention in the interview was the strategic use of Portuguese language in the exhibition. This was the most exciting feature to me, since it is a privilege to work in a context where using my mother tongue could have critical effect. The title of the exhibition is Continente, which is the largest chain of supermarkets in Portugal, akin to Albert Heijn in The Netherlands. ‘Continente’ also means a geographical continent, and I was intrigued to see how this wordplay could work in relation to my biography. In that sense, the Portuguese press release gives the visitor directions from my parents’ house to the nearest Continente in Viseu; I am in the car with my father, as he drives to A Maior and he comments how Continente is the only business model worth pursuing. The English press release gives directions to the nearest Continente to Kunsthalle Lissabon; the journey takes up the river Tagus, ‘up’ the continent, and I linked it to anal sex: going ‘up’ someone’s ass, fucking the continent.

ZIE DE KUNSTENAARSPAGINA’S VAN A MAIOR IN METROPOLIS M Nr 1-2018 LIFE & WORK. METROPOLIS M KRIJGT GEEN SUBSIDIE. STEUN ONS, NEEM EEN ABONNEMENT. ALS JE NU EEN JAARABONNEMENT AFSLUIT STUREN WE JE HET LAATSTE NUMMER GRATIS OP. MAIL JE NAAM EN ADRES NAAR [email protected]

Bruno Zhu – Continente, until 05.05.2018, Kunsthalle Lissabon, Lisbon

Domeniek Ruyters