In Memory of John Baldessari – Afraid of Sculpture

John Baldessari has passed away last Thursday. In memory of the artist we publish the latest conversation we have had with him in the context of his presentation at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht.

John Baldessari has often compared his distinctive approach as an educator to “just playing cupid.” Developed out of a necessity to extend his conceptually-textured studio practice into the classroom, his teaching philosophy can be characterized by an ability to orchestrate simple, workable situations in which art can occur. During his forty years instructing and experimenting in various Southern California art schools, Baldessari rose to international acclaim as a preeminent American artist, all the while remaining a committed and much esteemed teacher. A central figure to both Los Angeles and the art community at large, the artist continues to be recognized for his on-going cultural achievements and support of younger artists through mentorship programs, advisory boards, juried projects and honorary degrees. This year, the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht has named Baldessari the recipient of the B.A.C.A. prize in contemporary art, an award granted to artists regarded as a “driving force” of innovation. For the occasion, the museum has arranged for six students from the Jan van Eyck Institute to meet with the visionary artist, and will further demonstrate Baldessari’s reaching influence through an exhibition of artists with whom he has collaborated. As this is the first time the notable prize has been granted to an artist outside of Europe, Baldessari is honored but pragmatic, holding that it’s not wise to “believe one’s own press clippings.” It is precisely this down-to-earth attitude that distinguishes John Baldessari as a thinker, creator and veritable art guru.

I’d like to ask you about a certain quality in your work that really appeals to me as a writer; I read that an early ambition of yours was to become an art critic. And in fact, many of your early works used critical texts alongside images as a very basic way to communicate an idea. Your work also seems very critical of systems like language, signs and logic. Do you think artists should also be critics?

‘That’s a good question. I was, and still am, of the opinion that it’s good to talk to artists and to go to the source. But I also remember when CalArts [California Institute of the Arts] started, the critic Max Kozloff was teaching there, as was I. Max was living in Santa Monica and everyday we would drive to CalArts together and somehow we got into this very conversation. His response, I remember it so clearly, was “anybody who believes [what] an artist [says] about their own work is a damn fool.” I see what he’s getting at, that artists are too close to their work. So, I go back and forth. I’ve always felt that one of my jobs with teaching—starting way back when I was teaching at community college, then at the University of California San Diego, then at CalArts and University of California, Los Angeles—was always to have a very vigorous visiting artist program. The reason is so students can learn that real people make art. It doesn’t just come out of the blue. Demystification is upper most in my mind. I remember, I had Richard Price out to speak at CalArts in the early ‘80s, and afterwards one of the students came up to me and said, “Why is it that what an artist says about their work and what a critic says about the same work are always different?” I said, “That’s why we have artists, to promote that kind of conversation.” That really stuck with me. So, I guess both the artist and the critic are necessary.’

You have also remained somewhat critical of arts education and have often said that art can’t be taught. Do you still feel this way?

‘I think so. I first realized that when we started CalArts, which purposely had no set curriculum. Nobody could really figure out what was necessary to teach. I can think of great artists that don’t even know how to draw, see what I’m getting at? Drawing is not a necessity, but what is? The mantra we all had at CalArts was “no information in advance of need.” So, the student would decide what nutrition was necessary and if we weren’t able to provide it, we would find someone who could. My own idea about teaching was that students should know how to speak intelligently about their work; discuss it, and not with bull shit, but very clearly. One of the most articulate artists I know is probably Vito Acconci. Amazing! And there are artists on the other end, like Warhol, who don’t say much but their work is fantastic. I think it’s good for young artists to see both extremes. There is the danger that students can get too eloquent. I remember interviewing a potential grad student at CalArts and thinking, “My god, he should be teaching me.” And then I looked at the work and there was no connection. I’ve also said that good artists and their students kind of teach each other. So, my idea is a modified one that you can’t teach art, but you can establish some sort of ambiance where art could happen.’

What about the more experimental art schools, for example the Mountain School of Arts or the Sundown Schoolhouse here in Los Angeles; do you see these sorts of programs as being successful?

‘I know there are many DIY programs that I’ve only read about. I haven’t participated in any. But I do think that one of the most successful schools I’ve seen was in Frankfurt with Daniel Birnbaum [Städelschule Art Academy]. I’m still ambivalent about art schools. At the cost of going to a private art school, like Art Center in Pasadena or Otis, a young artist could just take that money and rent a studio [Laughter]. Well, I did go to Art Center for writing and critical studies, and while I was there, Lawrence Weiner came to speak. I remember that one of the main things the students took from his visit was that he was radically against art schools. Oh, tell me about it! He’s an old friend of mine. The students all found this ironic, given the context for his talk. Do you think his point of view is a viable option for young artists today? Can they simply rely on the museums and galleries and bypass the schools? If a young artist asks for my opinion about this, I always tell them the same thing, “Think about what you might use that tuition money for.” But students today see art school as a place to make contacts. I think, “Just go to openings and talk to people!” But then you don’t so much get the ambiance of what you might call a “professional” artist. In school, there are the resident artists and the critiques; you get studio space and you don’t have to work. I know L.A. very well and I think that one of the reasons there are very good art schools here is that really good artists will teach here. They don’t see it as a social stigma, whereas in New York, teaching might mean you’re not doing very well. Los Angeles is a good place for artists because there aren’t the distractions that there are in a place like New York, which is both good and bad. There, you can walk down the street a block and run into half a dozen artist who want to go have coffee or a drink. If I go outside here, I could walk for miles and never meet another artist. If I want to get together with other artists, I have to work at it and it’s not accidental. Another thing that counts for L.A.’s ascendancy is that it’s much cheaper to be here. It’s no longer possible to go to NY and find a loft space in SOHO. You can’t afford it. You have to go to Brooklyn and if you live in Brooklyn, then you might as well be living anywhere.’ [Laughter]

Do you find a similar climate for art making in European cities that you find here in L.A.?

‘Berlin is really doing well now and I think that’s because of cheap rents. Artists will always go where the rent is cheap. When the wall came down, I thought “Okay, Berlin will be the new art center.” But it never happened. Maybe it was too far east, but now people are moving there!’

The Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht recently named you the recipient of the B.A.C.A. International 2008 prize in contemporary art and this is the first time it’s being awarded to an artist outside of Europe. What does it mean for you to be recognized by The Netherlands as such an important artist as opposed to, say, your inclusion in this year’s Whitney Biennial in the states?

‘One of my first retrospectives was in Eindhoven [John Baldessari: Werken 1966-1981, Van Abbemuseum, May 22- June 21 1981] and there I became good friends with the director, Rudi Fuchs, and the assistant director, Jan Debbaut, who I later did a show with in Belgium. I’m really fortunate to receive this award. I think about it for a minute but then I forget about it. Maybe that’s just my upbringing because I never got much praise from my parents. I still feel like I’m just sitting in the back row of art class.’

That’s very humble.

‘Well, it’s not humble. I know it sounds that way, but I just… well, I think believing your own press clippings is a bad idea.’

As an artist, you seem to remain a bit detached in this way, but at the same time you are an incredibly dedicated teacher.

‘I just figure that’s my job. I first got into teaching to support myself and then I found that I had a knack for it. I really do like teaching and I think that one of the reasons that I was so inventive with it was because I just tried to avoid all the bad teaching I got [Laughter]. I just did the opposite! Like I said, I think this is what’s good about L.A. When I was at UCLA, I taught along with Paul McCarthy, Charles Ray, Chris Burden and Nancy Rubins; none of us needed the salary, but I think we all got something out of teaching.’

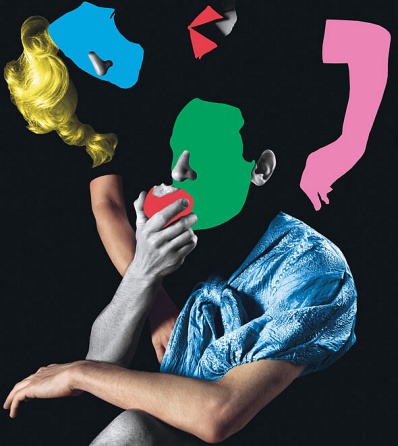

[figure 3440_2613_baldessari-07-h.jpg]

In addition to an exhibition at the Bonnefanten Museum this October, on the occasion of the B.A.C.A. prize, you also have exhibitions coming up in galleries in New York and Brussels and Museum Haus Esters in Krefeld. Will any of these exhibitions include more three-dimensional works like those recently exhibited in Bonn, Germany?

‘Well, I think I’ve always been fearful of sculpture because – no pun here – but I really have a two-dimensional sort of idea about art. I made a couple sculptures when I was a painter just to amuse myself. But I became bored with just having a single surface, so I decided to have three levels: a level a half an inch above the surface, the surface, and a level half an inch below the surface. It was pretty timid at first, but I guess this resulted in low-relief. I began to increase the depth so the paintings had some heft as real objects; then they just became shapes like foreheads and eyebrows. The most sculptural work I’ve done so far was shown in Bonn, where Beethoven was born. I had gone to the Beethoven House and was really taken with his cabinet of ear trumpets. I was working with ears and noses at the time and I guess – as artists will do – I brought the two together, the ear trumpet and the ear. I made six, six-foot tall ears that are about four feet across. Each one is programmed with different quartet by Beethoven and you can speak into the trumpet and it will play back a snippet of a quartet. But these still hang on the wall, you see. Now, we’re just in the planning stage, but for the Mies van der Rohe house in Krefeld I want to install something that is so anti-Mies; he would turn over in his grave! I’m having a couch manufactured in the shape of an ear. Not only that, but to the left and right, above it, on the wall, will be two upturned nose sconces. They will have lights, or you could put flowers in them I guess [Laughter]. I don’t think of this as sculpture. I just think of it as something and I’ve got to keep it that way. When I hear the word “sculpture” I just groan. It’s too frightening.’

Would you consider this design?

‘I think so. Once something becomes useful that’s what happens. People want art to be useful. It’s interesting, now that we bring up the subject, in the art market we’re seeing shows of furniture and design in the galleries. People are getting to see furniture as importantly as painting or sculpture or whatever. I guess that’s good. There is more and more a blurring of boundaries and I’m all for a blurring of boundaries, that’s for sure.’

Catherine Taft