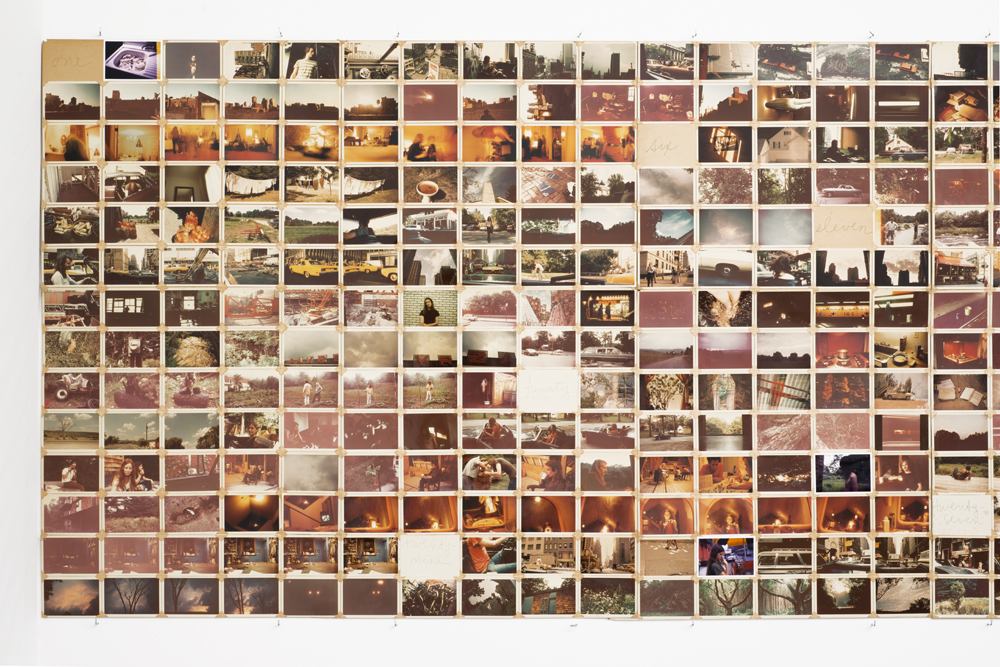

Bernadette Mayer, image from ‘Memory’ (1971-1972), courtesy: Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

Poetry’s best-kept secret – in conversation with Matthew Rana on the cinematic work of poet Bernadette Mayer

Continuing our series of interviews on PhD research and its researchers, Lena van Tijen talks to Matthew Rana about his cinematic approach to the intriguing work of the American poet Bernadette Mayer. “There are some aspects of her work that cinema seems to account for in a more useful way than poetry or art can.”

On the 22nd of November, I meet Matthew Rana at Café de Jaren in Amsterdam. The café is located near the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Amsterdam where Rana is currently conducting his PhD research at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis (ASCA). His research From Memory to Reproduction: The Cinema of Bernadette Mayer centers on Bernadette Mayer, the American poet who has frequently been grouped with the Language poets and the New York School. A poet, so explains Rana, who for many years was described as poetry’s best-kept secret.

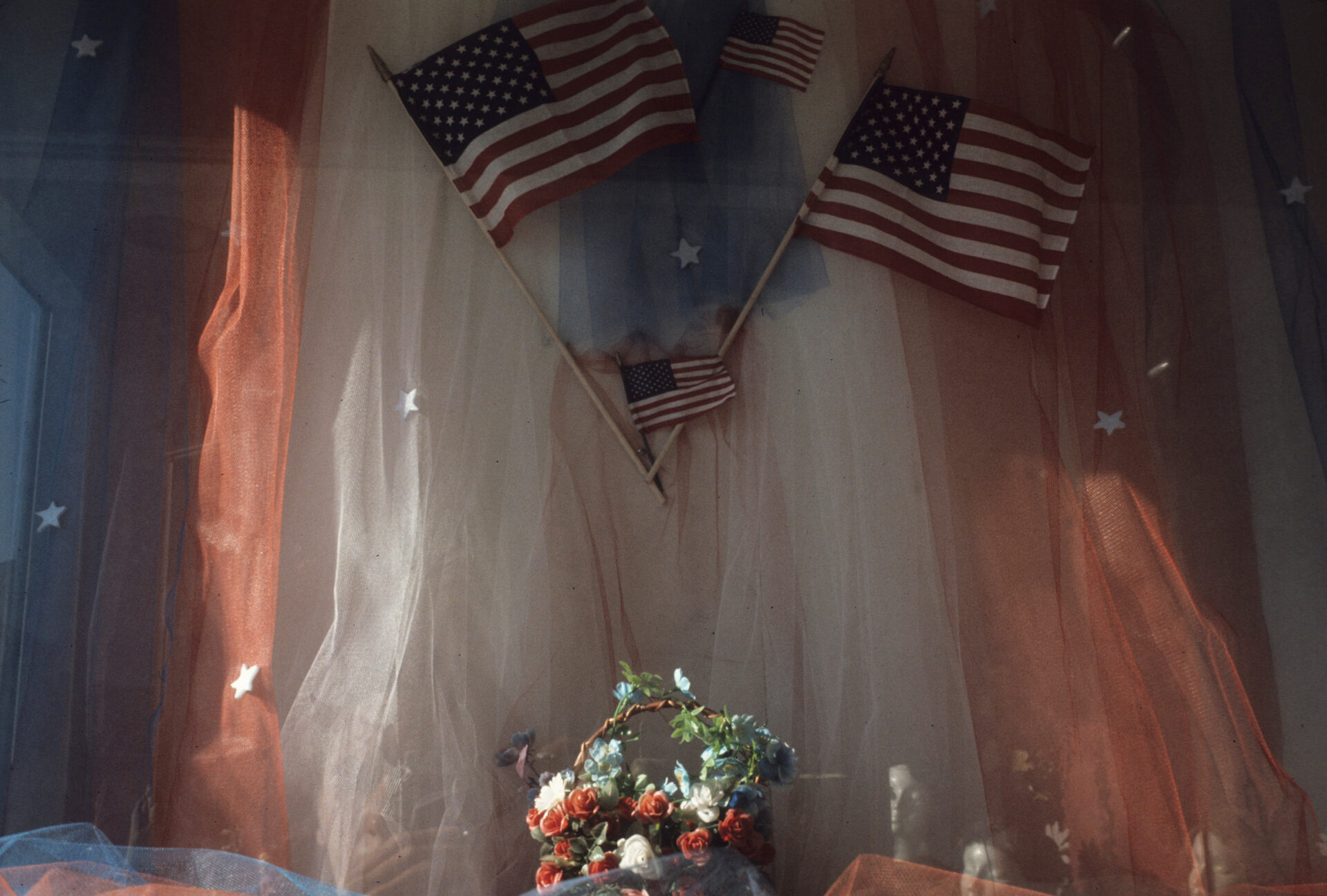

Bernadette Mayer, image from 'Memory' (1971-1972), courtesy: Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

In his research, Rana claims that a cinematic approach to Mayer’s work, and in specific to her conceptual art project Memory (1971) and her 450-page diary Studying Hunger Journals (2011), might offer a new perspective on her writing. He also claims that one might even perceive Mayer as a filmmaker of sorts. The definition of cinema Rana uses differs from how it is usually described; mainly as the art of moving pictures. In line with film historian Thomas Elsaesser, Rana approaches cinema as a “media/memory constellation”, meaning that he sees it as a technology that is not just shaped by its user but that shapes its user as well. Rana is a self-funded PhD candidate at ASCA. He hopes to finish his dissertation in 2025.

Memory is a piece that Mayer did in 1971. It is a project where, during July 1971, she shot one roll of 35mm slide film every day for the entire month

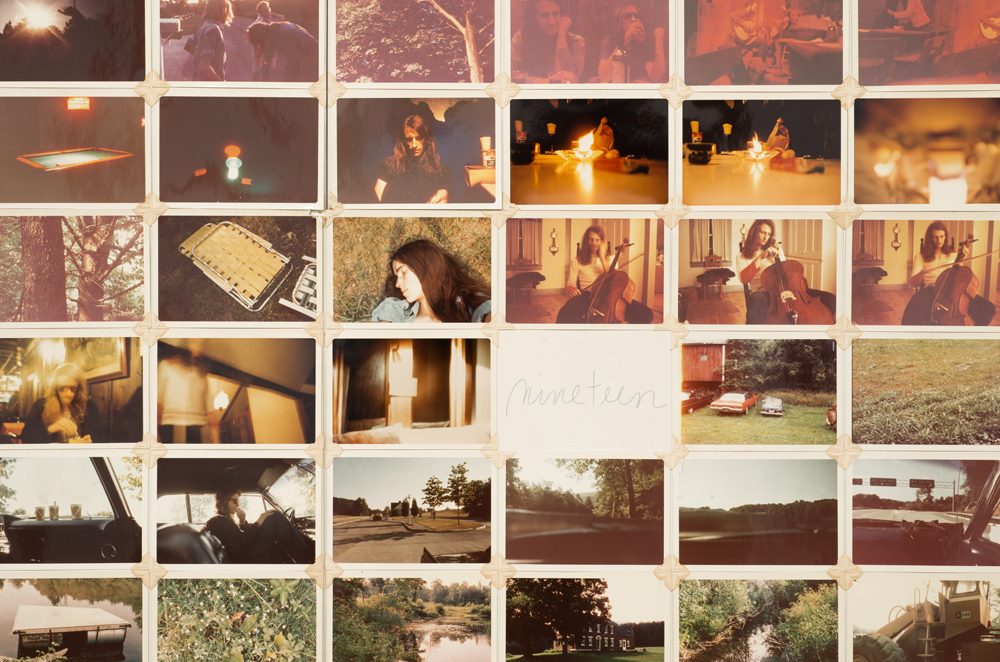

Bernadette Mayer, 'Memory' (1971-1972), installation at CANADA, courtesy: CANADA, New York and Joe DeNardo

Bernadette Mayer, 'Memory' (1971-1972), installation at CANADA, courtesy: CANADA, New York and Joe DeNardo

For the past two years and alongside his PhD research, Rana has been trying to bring Mayer’s installation Memory to the Netherlands. He has not yet found an art institution willing to put it on display. Rana, who grew up in New Mexico and is currently living in Stockholm, has moved back and forth between the fields of visual art and poetry for some time. He began his practice as a visual artist by doing an MFA in Art and Social Practice alongside a MA in Critical Studies at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco. After graduating, Rana did a postgraduate teaching fellowship at Valand Art Academy in Göteborg. Since he moved to Sweden permanently in 2015 his practice started moving away from visual arts and into literature and writing. Out of economic necessity, Rana works as an art critic but his primary practice is as a poet and researcher. He has a book coming out later this year at Nion Editions, a small press that focuses primarily on “uncategorizable forms” such as works-in-progress and thought experiments.

How did your interest in the work of Bernadette Mayer begin?

“I suppose it was around 2013 or 2014. I was transitioning away from my visual art practice and was quite interested in what the poet, publisher, and critic Patrick Durgin calls the ‘new life writing’ of the 1970s and 80s, particularly the work of poet Hannah Weiner. At that time, I was seeking out tendencies in writing that bridged the gap between conceptual art and poetry. It was through Weiner’s work that I came to Bernadette Mayer, specifically to her book Studying Hunger Journals. It’s a 450-page journal that she kept while she was in psychoanalysis.”

I read parts of Studying Hunger Journal, and it reminded me of a stream of consciousness. What interests you about this mode of writing?

Bernadette Mayer, image from 'Memory' (1971-1972), courtesy: Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

“I was interested in experimental autobiography, so that is how I first encountered it, as a way of writing the self. With that particular book, it was the way that it seemed to both encourage my reading and resist it. Publishing your analysis notebooks is a very vulnerable gesture. But at the same time, the prose is so dense and relentless that it undermines the intimacy and the transparency that that gesture implies. It really felt like I was stepping into someone else’s mind, and it was totally overwhelming. Fairly soon thereafter I also encountered Mayer’s work Memory, the book not the gallery installation. Memory is a piece that she did in 1971, it is one of the works that cemented her status as one of the foremost members of the downtown scene in New York. It is a project where, during July 1971, she shot one roll of 35mm slide film every day for the entire month. At the same time, she kept a detailed journal of her activities, and then, at the month’s end, after the film had been developed, she made an audio recording where she responded to every slide. After that, she took the journal that she had been keeping and the audio transcript and cut them up, and made an audio script. The audio script was then shown along with prints made from the slides which she assembled in a grid that was around 10 meters long, containing over a thousand photographs. She thought that through the combination of sound and image viewers could actually experience what it was like to be her, so it is also a kind of experiment in consciousness. Its first showing was in 1972 at Holly Solomon’s 98 Greene Street Loft.”

“Cinema is not only an optical phenomenon that privileges aspects like the gaze, active-passive binaries, subject-object binaries, and issues surrounding identity and identification. It’s also a means to record and reproduce, a mode of inscription and writing, in fact”

Bernadette Mayer, image from 'Memory' (1971-1972), courtesy: Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

Bernadette Mayer, image from 'Memory' (1971-1972), courtesy: Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

When did your interest in Mayer’s work turn into research?

“I did a performance-lecture in 2016 called A Form Adequate to Memory: 36 Fragments for Bernadette Mayer where I wrote 36 fragmentary essays in dialogue with her work. One of the fragments that I wrote was: ‘Memory is and is not cinematic.’ And this condensed thesis continued to preoccupy me. The premise of my current research is that Mayer is a kind of filmmaker. In it, I try to trace different cinematic logics that are at play in her work from the 1970s.

Why is it important to recognize Mayer as a filmmaker of sorts?

“I’m not sure she needs to be recognized as a filmmaker, but there are some aspects of her work that cinema seems to account for in a more useful way than poetry or art can. That all of her major works from the 1970s use durational constraints, for instance. In the case of Memory, it was a month; in Studying Hunger Journals, it was this three-year period of psychoanalysis; in Midwinter Day (1982) – a supposedly real-time transcription of her day that she kept during the winter solstice – it’s 24 hours; and then, for the last book, The Desires of Mothers to Please Others in Letters (1994), it’s a pregnancy. Those are the four books that I’m looking at.”

In your research abstract you write that you approach cinema as a “media/memory constellation”, a term you derive from film historian Thomas Elsaesser, rather than seeing it as an “image-making technology based on optics”. How do you define the term cinema in your research?

“In Freud and the Technical Media: The Enduring Magic of the Wunderblock (2011), Elsaesser proposes viewing cinema from the side of reproduction, as a media/memory constellation that incorporates ideas about the encoding, storing, and processing of information. He reconceptualizes cinema broadly as one among many technologies for storing and transmitting information, including alphabetization and punched cards. That’s more or less the line that I’m taking: cinema is not only an optical phenomenon that privileges aspects like the gaze, active-passive binaries, subject-object binaries, and issues surrounding identity and identification. It’s also a means to record and reproduce, a mode of inscription and writing, in fact.”

During your research, did you find that Mayer was directly influenced by cinema?

Bernadette Mayer,'Memory' (1971-1972), detail, installation at CANADA, courtesy: CANADA, New York and Joe DeNardo

“Her partner at the time she made Memory, Ed Bowes, was a filmmaker. She also had practical experience working with film and video. For example, she was once an assistant editor on an unreleased film and she also made videos for her poetry readings, which, unfortunately, are now lost. She admires Jean-Luc Godard, Agnes Varda, and Jonas Mekas whose film diaries Memory bears a striking resemblance to, visually. But when I’m talking about cinema in relation to her work, it’s really less about the direct influence of particular filmmakers and more about tracing the cinematic logics that are transferred into her writing.”

“Mayer writes that she wants ‘to prove that the day like the dream has everything in it’”

Bernadette Mayer,'Memory' (1971-1972), detail, installation at CANADA, courtesy: CANADA, New York and Joe DeNardo

What are the benefits of approaching Mayer’s work through a cinematic lens?

“Questions relating to psychoanalysis seem to be coming to the fore again and again in different ways. Other scholars have commented on Mayer’s interest in the subject, notably Maggie Nelson in her book Women, the New York School, and Other True Abstractions (2007). But this has not yet been thoroughly unpacked. For me, what a cinematic lens suggests is that psychoanalysis is inscribed in Mayer’s work in ways that are more complex than previously acknowledged. But so far, I’ve been focusing on Memory and Studying Hunger Journals which have closer links to psychoanalysis, especially the latter.”

Using psychoanalysis today as a framework to discuss the work of a female artist might be criticized. How do you respond to such critiques?

“People are resistant to a psychoanalytic reading. Which is understandable, given its problematic history of misogyny, homophobia, and transphobia, among other things. I tend to side with thinkers like Juliet Mitchell who say that psychoanalysis is not a recommendation for heteropatriarchy, but that it is an analysis of one. As such, it gives us a lot of tools to break down that kind of violence. I think that psychoanalysis still offers us ways of thinking about sex, for instance, that emphasize its ambiguity and help us to think outside of sexual binaries and dimorphism. But this is an unpopular stance today, as it was during the 1970s. I’m not invested in psychoanalysis necessarily, but it was engaging with Mayer’s work that led me there. The question is: how is she working with it? Because, in addition to critique, I think there is more agency, inquisitiveness, and use there than it seems.”

A question Bernadette Mayer keeps returning to in her Studying Hunger Journals is: “to leave all out or to include all.” Why is this question so important to her and, in turn, to your research?

“It is a question that keeps coming back throughout all her works from the 1970s, I would say. In fact, I think, to varying degrees, all of her books from that period try to negotiate whether to include all or leave all out. But it’s more than an archival dilemma or even a methodological problem about how to edit. It’s also about getting out of binary thinking. In Midwinter Day, she writes that she wants ‘to prove that the day like the dream has everything in it’. If we follow Freud, in dreams there is no such thing as ‘either-or’, only simultaneous juxtaposition; it’s a matter of ‘both-and’. So, I think that part of what she’s getting at is how do we make the simultaneous existence of all these contradictions legible and thinkable. Of course, there is also a sense in which the unconscious can be thought to include all and leave all out, in terms of memory and repression and so on.”

When reading the articles you wrote in the context of your PhD research, I am reminded of what Jacques Derrida calls “archive fever” and its antithesis “death drive”. For Derrida, the two terms represent how the need to remember is always followed by the equally pressing desire to forget. Do you recognize these opposing forces in the work of Bernadette Mayer?

“These competing impulses are always at play in Mayer’s work. On the one hand, there’s this desire to document and record everything, and on the other is this relentless negativity around which everything seems to turn. But one of the other points Derrida makes is that the archive is not just orientated toward the past, but is trying to establish something for the future. I think that one of the great things about Mayer’s work is how it seems to anticipate so much about our present moment. The emerging consensus around Mayer, especially following the 2020 reprint of Memory by Siglio Press, is that she anticipated our relationship to digital photography. But I think she anticipated way more than that.”

What else did she anticipate?

Bernadette Mayer, image from 'Memory' (1971-1972), courtesy: Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

“I think she anticipated something about how we produce ourselves or are produced as subjects today.”

For the past two years and alongside his PhD research, Rana has been trying to bring Mayer’s installation Memory to the Netherlands

Bernadette Mayer, image from 'Memory' (1971-1972), courtesy: Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

Has your academic research impacted your poetry?

“Reading Mayer’s work closely has given me permission to try all sorts of things. I’m using constraints more, for instance. I’m also more inclined to go back to traditional forms. This doesn’t get talked about much, but Mayer grew up Catholic and was educated at a Catholic school where she learned Latin and Greek. So, she knows the classics well and often returns to them. For example, she did an amazing translation of the Roman poet Catullus some years ago called The Formal Field of Kissing (1990). As avant-garde and experimental as her work may be, it is never ahistorical.”

What has your research into Mayer’s work brought you?

“I was just beginning to learn about poetry when I first read Mayer’s work, and it expanded my idea of what a poem could be, what it could include, and what it could do. That initial fascination, that bewilderment, that astonishment in the face of her work is what this research is really about. I’m trying to think with her work, which is so complex. And partly that’s why I wanted to do a PhD. because it felt like I couldn’t do it by myself.”

The day Matthew Rana and I spoke in Amsterdam Bernadette Mayer passed away at the age of 77 at her home in East Nassau, New York. For some time, I didn’t know how to respond to the email Rana send me the day after our meeting in which he informed me of her passing. From our conversation, it was clear that he was not just academically but also personally affected by her work. Even when using academic jargon, Rana’s admiration for Mayer was clear. I cannot think of a better reason for writing a dissertation than his sincere desire to understand her work. The poet’s passing does not necessarily change the course of Rana’s research. His attempt to bring Bernadette Mayer’s Memory to the Netherlands has, however, gained an urgency that I hope will also be felt by Dutch art institutions.

Lena van Tijen

is a writer