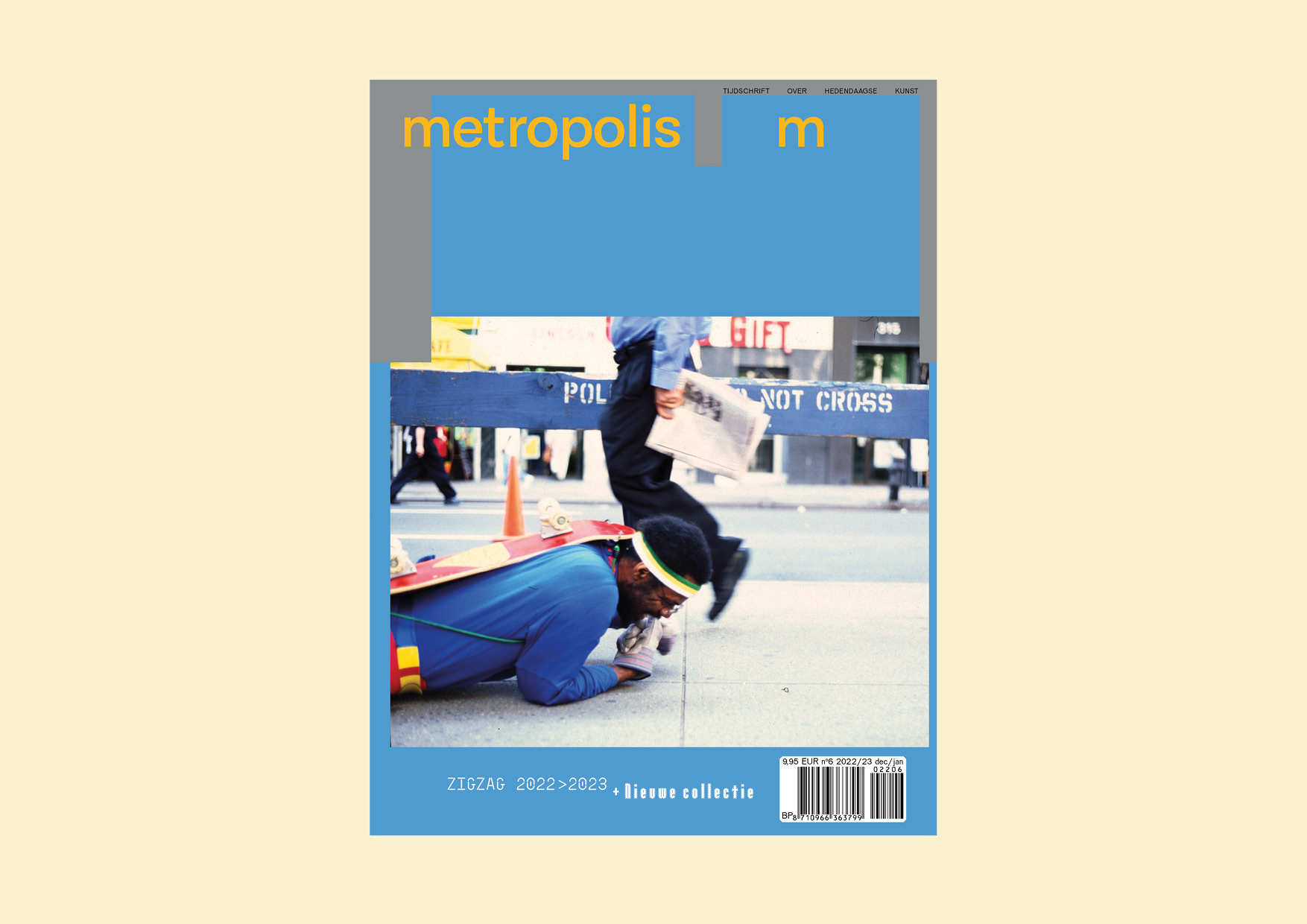

David Chichkan, ‘anti-authoritarian troops of Ukraine’, 2022

‘All the cultural life we had has been destroyed’ – In conversation with Vasyl Cherepanyn

Although the current war in Ukraine is being followed closely, Western Europe has not always paid equal attention to the eastern part of the European continent. With major consequences, according to Vasyl Cherepanyn, co-founder and director of the Visual Culture Research Centre in Kyiv that also organizes the Kyiv Biennial.That lack of interest may well have paved the for the Russian invasion. A recalibration of perspective is needed to recognize these contemporary forms of colonialism, Cherepanyn argues, and the role of the cultural sector in it. ‘I think there is a kind of repressed coloniality that does not allow the European Union to embrace the other European experience.’

What are the effects of the war on artists and curators around you in Kyiv?

‘It looks very different for everyone. Many have scattered across the country or fled abroad. In general, the cultural world that we used to have before the 24th of February 2022, has been completely destroyed. There were some attempts by institutions to open exhibitions during the quieter summer months, but in recent weeks the heavy bombing made it clear that this is impossible and also irresponsible. All the cultural life we had has been destroyed. Forever. The artists and cultural workers who were able to leave are working abroad to make the international public more conscious about certain developments. For me, it is perhaps more important to reverse the question and ask the cultural sector in EU countries what it is like for them. The main problem is that various audiences in the EU have been watching the constant destruction of life in another European country for the past eight months and have done almost nothing about it. The EU countries seem to basically agree with this war; they did not do anything to prevent it and only reacted to developments on the ground. I think this war is the greatest catastrophe for European democracy, but people have not yet fully understood its implications. Neither have people in Ukraine. It is still unclear how the situation will develop, but this inaction is a very destructive reaction and the consequences will haunt the European Union for years to come.’

In response to a question from the audience after the Freedom Lecture you delivered at De Balie in Amsterdam in July this year, you said that many people have difficulty understanding the times in which they live. Is the Western European passivity you speak of related to this inability?

‘Of course, it’s very painful even just to talk about these terrible realities, and I can fully understand that people who are elsewhere keep away from them. Let me put it this way: the wave of real political solidarity in the form of economic sanctions and embargoes against Russia from European and Western governments was only possible thanks to the unprecedented pressure from European society. In this, journalists and the media played a huge role, but I think for the cultural domain, especially in Western Europe, it has been a missed opportunity.’

In what way?

[answer Vasyl Cherepanyn] ‘Instead of putting pressure on the government, instead of demonstrating more, instead of showing more outrage, more anger, in the first weeks of this fascist, colonial war cultural institutions were afraid to cross their institutional boundaries. They resorted to the white cube, running programs and helping refugees, for example. This is always much needed, of course, but this moment of resistance was lost. Unlike many other sectors, the cultural field has global connectivity and can have a very direct impact on society. Sociologically, cultural institutions also have potential political power. Honestly, I still wonder what all these institutions were afraid of. Of course, they were reacting to the war, but it can be argued that for many Western-European institutions it became a backdrop for their own contemplations, imaginations and fantasies about the reconstruction of a future Europe. It was a way to avoid having to deal directly with harsh realities. But having lost this opportunity, we are now all – the cultural field, the media, the general public – waiting for another catastrophe. It is no coincidence that there is now talk about the nuclear threat, ecological disasters and the atrocities Russian troops are committing on the ground on a daily basis. Forty per cent of Ukraine’s energy infrastructure has been damaged in the past two weeks, but nothing seems to be enough. There is an unspoken demand for more misery, as if what has already happened is not enough. Many contemporary art institutions claim to be politically engaged and radical, but when the time came they did not act. They concentrated on their own cultural logic in their own bubbles, apart from some topicalities that are tackled from time to time. The obscene truth is that many in the EU act as if this war is someone else’s war. It is as if there is something wrong with the perception of time.’

How do you mean?

‘European countries and institutions always act with delay. Dutch history is symptomatic in that regard. As far as I know, the Netherlands was neutral in World War II until it was occupied. For me, this is a telling example of what it means in practice to be neutral today. Unfortunately, this historical reference comes up also because the current war has been deliberately stylized and executed by the Kremlin on the same scale as World War II. The European Union emerged as a peace project from the aftermath of World War II, under the slogan “never again”. There has been a lot of talk in the EU over the past seven decades about history and how the past has shaped today’s society. Thinking out loud, I then wonder: what is history if not the knowledge of time and what time means, the knowledge of how to act in time? If you talk so much about history but at the same time have a timing problem, perhaps there is something wrong with the story you present about yourself and about a united Europe. I think this kind of self-deception is strongly related to the neglect and suppression of the realities of Eastern Europe. There is still this division between the EU and the rest of Europe. Even parts of Eastern Europe that are part of the EU are still considered not the “real Europe”. To include the perspective and modus operandi of the rest of the continent would mean changing the whole idea of what a united Europe is, and what is considered inside or outside. I think there is a kind of repressed coloniality that does not allow the Union to embrace the other European experience. We often criticize this business-as-usual model in politics, but I think unfortunately it is also very present in culture. Decolonial thinking has become mainstream recently, and what strikes me is that despite its claimed progressiveness, it is often nationalized.’

David Chichkan, 'anti-authoritarian troops of Ukraine', 2022

In what sense?

‘In any country, whether it is the Belgian, French or Dutch art world, most discussions of decoloniality relate to one’s own national imperial past. This decolonial thinking is not applied to the present and to other parts of the same continent. In Western Europe, most people are so used to the comfortable dichotomy of Global South and Global North that when you talk about colonialism in Eastern Europe, you have to completely adjust your frame of reference to understand this different perspective of the colonial present. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the EU did not treat the eastern part of the continent as part of the common European home. Thinking of Eastern Europe as peripheral produced very direct and real political results. It is exactly this kind of policy that defined Eastern Europe as secondary, it is this policy that exposed so many countries, especially post-Soviet countries, to the Russian imperial grip. It is not just about Ukraine, but also about Belarus, Moldova, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Georgia, the entire Caucasus, Dagestan, Kalmykia and countless other national republics that are currently subjugated to the Kremlin control. Together they comprise a huge portion of the European continent that has been under direct military occupation by the Russian empire for many decades. You have to reconfigure your optics, the way you approach other parts of Europe and what you think Europe is, to understand this form of colonialism and recognize the anti-colonial struggles and practices from these countries. There is a task here, especially for the Western European cultural field. I hope Ukrainian artists can also help raise that awareness.’

We began this conversation with a deep disappointment in the cultural field, but now you identify a role it could play to help de-escalate current situations and perhaps prevent future ones.

‘Exactly. This is about thinking ahead.’

Since the outbreak of the large-scale war, the focus has shifted somewhat and Ukrainian artists and curators are now working at the intersection of art activism, political activism, journalism and even forensics. One of their main occupations is documenting Russian war crimes

Have the past few months affected how you think about the role and agency of art?

‘When it comes to art, for me the most direct parallel in relation to the current reality in Ukraine is the German expressionism of World War I and the interwar period. The work of Emil Nolde, Otto Dix or Max Beckmann, how they depict their society – the distortion, harshness, isolation, the presence of veterans, the war victims – reminds us of the reality in my country and what we will experience in the coming years. Today’s Ukrainian art can be defined as political expressionism. Since the Maidan revolution, politics has been a natural part of the cultural modus operandi, something that is unique in Europe. This revolutionary experience of networking and solidarity has contributed enormously to how artists work: not as individual artists, but as citizens united in certain forms of collectivity. Since the outbreak of the large-scale war, the focus has shifted somewhat and Ukrainian artists and curators are now working at the intersection of art activism, political activism, journalism and even forensics. One of their main occupations is documenting Russian war crimes. Many are evacuating art collections from museums or private collections, especially in the east and south of the country, or setting up temporary emergency residencies for cultural workers from the more damaged regions. To return to your question, talking about the agency of art is very fashionable both in the East and in the West. To me, such questions are a bad sign because it means that something has been lost in the political sphere, shifting this kind of direct political action to the artistic realm. I would rather turn the question around: what can we do to restore the agency of art and bring about political change? Ukraine is the best example of how art should be highly political and accompany a political emancipation process, but it should not be a substitute for real political change, which is always created by people, by people’s bodies. If there is a genuine social movement towards emancipation or liberation, art will be inevitably part of it.’

Vasyl Cherepanyn (Ukraine, 1980) is director of the Visual Culture Research Center (VCRC) in Kyiv, is a platform for collaboration between artists, activists and academics, which he co-founded in 2008. The VCRC is an important hub of Ukraine’s cultural sector and organizer of the Kyiv Biennial, which is a founding member of the East Europe Biennial Alliance. As a cultural research center, it deals with important political issues, such as the position of former Soviet countries in the EU, the alarming rise of the far-right in Europe and the Russian-Ukrainian war conflict. Cherepanyn lectures at several universities, both in Kyiv and other cities in Europe, and works as a curator and editor.

A DUTCH VERSION OF THIS INTERVIEW IS PUBLISHED IN METROPOLIS M NO 6-2022 ZIGZAG. ORDER HERE: [email protected]

Zoë Dankert

is final editor at Metropolis M