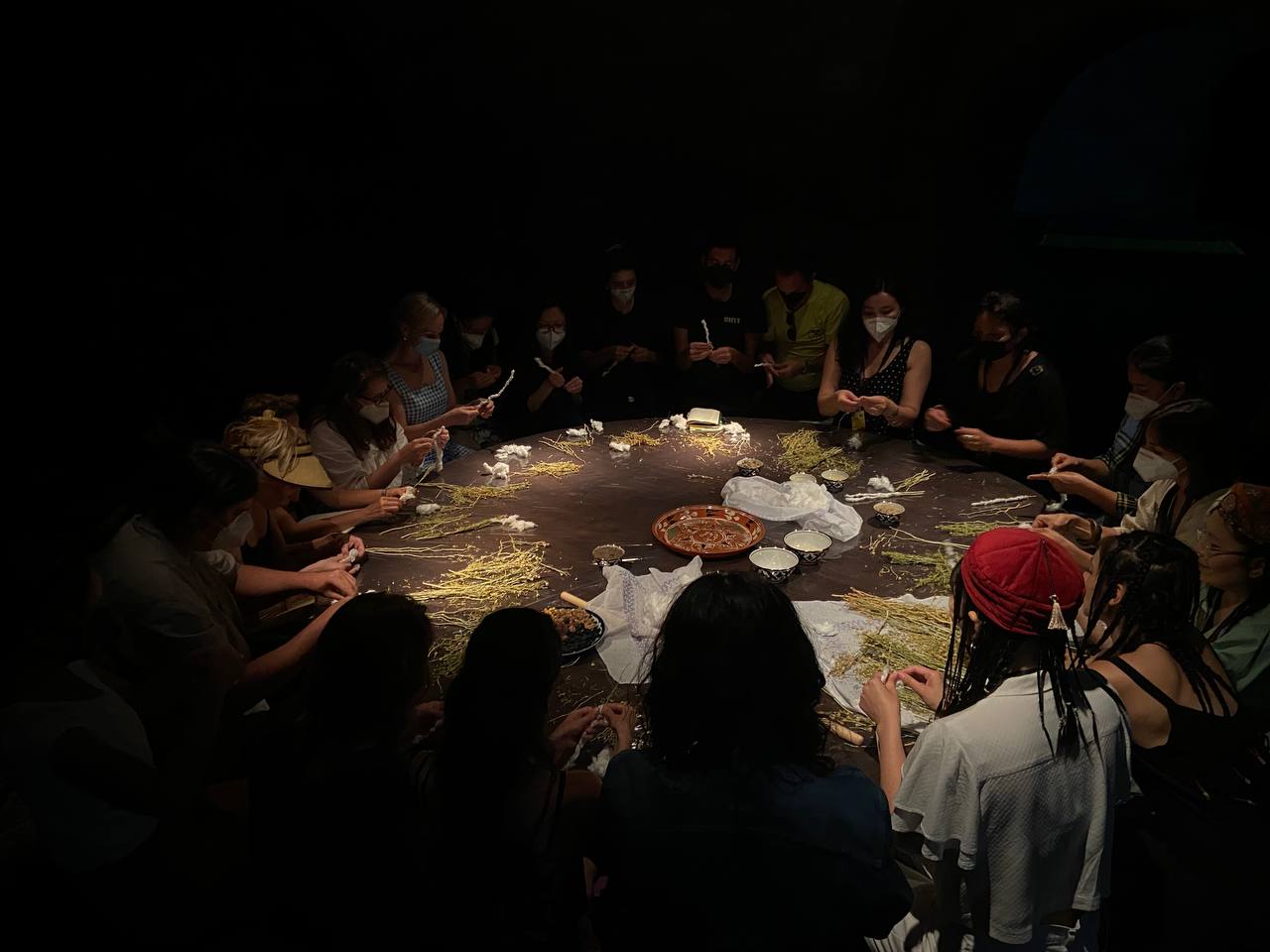

DAVRA collective public program at documenta fifteen, photo: courtesy of DAVRA

Creating circles, but not for the sake of the circle – an interview with DAVRA collective

Talking to the Central Asian research collective DAVRA (its most famous member Saodat Ismailova currently has a show at Eye) about its series of events under the title Winter Chilla. It takes place across four different cities in four different countries: Tashkent in Uzbekistan, Almaty in Kazakhstan, Bishkek in Kyrgyzstan, and Dushanbe in Tajikistan, during the forty coldest days of the year (19 December through 3 February).

I have learned that the word ‘davra’ means circle. How did you decide on the name DAVRA and what is important for you about the idea of a circle?

‘The word “davra” is of Persian origin. The most significant thing about Turkic and Persian languages, the languages of the region that we are living in, is that they are very metaphorical and poetic. This means that sometimes one word can mean a lot of things at once. A “circle” can mean a circle of people, a place to gather, or a group of people with whom you gather. For us, even in terms of installing and curating the Chilltan programme at documenta, the main space of DAVRA was around the khontakhta, a huge round table. This meant inviting others to join our davra for reflections or collective action and practices, or anything else through discussions, so it was the most natural word that came to us. Our experience at documenta fifteen was very fresh for us, not only as members of a collective who have gathered from all over the world. We are all from the same region, but we are from different countries that have been ideologically separated for a while. It has been nice for us to find connection points and differentiations by coming back to the world of the circle, creating the circle or gathering around the circle.’

DAVRA collective public program at documenta fifteen, photo: courtesy of DAVRA

‘The shape of a circle was an easy one to choose. In our region, the people understood the universe and the world around them as round. That could be traced through different elements of how they portrayed the world on textiles, as well as through stories and oral histories.

‘Davra’ should not be understood as a circle that is created for the sake of creating a circle, it is usually a circle that is created as result of a process. This could be people eating around the table or people doing something in a circle, just like we did in documenta by cooking manty or making a ritual. We were digging into the rituals, into cosmologies, into the world, and into understanding of identities that were living in us or were part of us. Identities that were kind of forgotten and haven’t been talked about in our colonised and modern world. For me, personally, it was going back to the understanding of the world that was in some way silenced. That process itself is part of what creates DAVRA, through the actions that we are doing, and the intention behind them which naturally creates a circle. DAVRA is, rather more, these processes and participation in these processes, to be able to understand and re-understand or redefine our own identities.’

‘In our region, the people understood the universe and the world around them as round. That could be traced through different elements of how they portrayed the world on textiles, as well as through stories and oral histories’

What was apparent from your circle, the work and your publication is the presence of predominantly female voices. How important are the female voice, gaze and oral histories?

‘We discussed femininity as at some point the group became all female, but we don’t really know why. There could be different reasons, of course. For us, the most important point is that we are all looking for our own agency, not only as females but in connection to national identity or regional identity. I think it could also really be the impact of colonialism, as a lot of these rituals were passed on from mother to daughter. Of course there were more rituals, but they were not passed on and vanished.’

DAVRA collective public program at documenta fifteen, photo: courtesy of DAVRA

‘I’m trying to research the traditions and ritualistic practices of Central Asia. Personally, I was always surrounded by these happenings or activations when growing up. There would be other members of the family, who were always women, like my aunts and my mother. As a child I was always rejecting the idea of these situations, but since a few years already, I realised that by practicing them, researching them and finding out what you have to do in a certain ritual, the ritual becomes more of a reclamation of an identity that was meant to be erased.’

‘The most important point of this time, for Central Asian countries, is that we are finally in the moment in which we are the ones creating our trends for ourselves, and that we are following them together’

Speaking of national or regional identity: through your research you are crossing national borders. How do you navigate cultural similarities or differences?

‘I think the complexity of this question is in the fact that the creation of national identities started during Russian imperialism and the Soviet era, when the region got divided. The cultural similarities are due to the historical past, because although the region is divided, it comes together in rituals. It is also in the reality we’re living in, the politics and the socio-economical statuses that we have today. Our countries became independent around the same time, which means that the trends and the downfalls that we followed are the same. The most important point of this time, for Central Asian countries, is that we are finally in the moment in which we are the ones creating our trends for ourselves, and that we are following them together. In terms of arts and culture, I see that there is a shift happening: we are finally impacting each other rather than being impacted by someone else from outside of Central Asia. I see a lot of collaborations between musicians, artists, researchers, journalists, documentarists and more. It’s one of those moments where we are looking for and looking into our own relations to each other beyond rituals and beyond the historical past and ancestral heritage.’

Do you see these rituals as something that can be used as a tool to go forward together rather than as a way to reconstruct your past?

‘The ritual itself can be something symbolic. For example, the burning of cotton sticks that we did at the opening of documenta is both a ritual and at the same time something that my grandmother used to do. However, as soon as the DAVRA exhibition ends and we move forward with our normal lives, burning something doesn’t bring me the healing for the challenges that we face today. Instead, it could be an attempt for us to create our own rituals to be more conscious or more proactive when thinking of these challenges. All of the members of the collective are from the younger generation. We are all born around the beginning of the nineties, at a time when all of our countries were in a crisis period. The challenges that we face today are quite similar, so when a story is being told by a Kazakh, Tajik or Uzbek colleague, I can understand the context or the situation. The act of a ritual could be one of the ways for us to experiment, to research, to understand. In this case, the ritual is much broader than what my grandmother used to do.

What DAVRA did at documenta was one of the starts as we were looking into the past to understand our origins. We got a Russified education of history, which was filled with storytelling that was not originally told by the people and this means I also know very little as I do not have the real sources. The ritual, for us, is an attempt to understand our own past to be able to face the reality today.’

DAVRA collective public program at documenta fifteen, photo: courtesy of DAVRA

‘We can look into the past, we can learn from it but we cannot construct our whole lives around it. The reconstruction of the past is very dangerous because it can go directly the opposite way of the beliefs that you believe today. It’s more important to learn and to look at it and also to get concerned and to question. Our history is very fluid and very flexible and it was written in that way as well. The researchers who wrote it down for the first time were not local, which already makes it a very questionable fact when you’re looking into these types of materials. All of a sudden, you are faced with the reality that this could be manipulated in any way wanted.’

‘We got a Russified education of history. The ritual, for us, is an attempt to understand our own past to be able to face the reality of today’

You’re talking about the stories of real people versus written history. This makes me wonder what DAVRA’s research looks like?

‘The research we do is not a classical type of research where we would interview people and afterwards share findings. It was more like individual projects that we were researching through the work that we were creating. On one side we were reading academic texts and exchanging stories, but on the other side the research was more internal. This meant that we were using the information and the perspectives we had as a fuel to make public works and a publication. In these projects, the sharing itself became the space around the table, and in the rooms where each one of us presented our work, it invited the public and the participants to be part of it.’

‘Each of our research approaches are quite different. For example, Jazgul’s main theme was about migration workers who are sacrificing their lives for the future of their families and country. In my case, I went to the realm of my family and kept talking to my mother and grandmother. We also had reading choices of books and texts that Saodat Ismailova shared with us. On top of that, we invited several lecturers who gave their opinion on the subject. It was really interesting to collect and combine all of these sources. In terms of the relations inside of the group, it was really great that we could take all this knowledge in and reshape it to our own understanding. The text that we planned to read during the opening ritual was written by a soviet anthropologist and researcher, but the way that the events were described in the text was always written in a masculine gender. We asked ourselves, how could he know what gender these entities belonged to and if they were gendered at all? We decided to rewrite the text to make it non-binary and changed all the pronouns to “they”. We had a lot of different directions for each of us, and we had a lot of freedom to reinterpret our own research; to tweak and to pick out some things that we found more relatable to us today.’

This freedom of reinterpretation is very inspiring for me., especially your way of relating it to the struggles of today. Is there something you are working on now, after documenta fifteen?

‘We are planning a small mirroring programme of events in Central Asia, which will be called Winter Chilla. It will take place mainly in Almaty and Tashkent, with some smaller events in Bishkek and Dushanbe. We will start on the first official day of the winter chilla: the forty coldest days. The series of events will be hosted by local organisations and institutions. It’s really quite incredible that, although we do not have a physical space and we do not have the access to the same equipment that we had at documenta, the programme is still going to happen with the help of the community. What’s important for us is that the winter part of the programme connects with the region, as not many of our colleagues were able to come to documenta to see it first hand. This is our attempt to share the experience in the region. We want to continue the sense of lumbung that was created by ruangrupa. There will not be forty days of events like we hosted in the summer, but these events will be just as important and as influential.’

DAVRA collective public program at documenta fifteen, photo: courtesy of DAVRA

‘The strange thing for me was that documenta fifteen was really just a rehearsal, but the real Chilla is going to be in Central Asia. In Kassel, mostly Western people observed the rituals, but our own folks know them in their guts, so it would bring an opportunity to go into a deeper conversation and interaction. Where there is a depth, there is also a vulnerability. I am feeling more excited and anxious about this than I did about Kassel.’

‘There is plenty of place to think and to discuss’

It’s great that you have so much support and that you’re able to bring this back to your community, where there will be a lot of input which will expand everyone’s horizons. It’s very exciting, I wish you good luck and I very much look forward to the Winter Chilla. And the final question: what does the future of DAVRA look like for you?

‘I believe that with DAVRA, as a research group, we are developing. At the end of documenta, I realised that this is only the beginning for us, it is really just a first step. We will continue meeting online, or maybe physically, in small groups as this is the reality we have today. Unfortunately, we cannot afford to just fly in whenever we want, but maybe there is beauty in that, as we are able to maintain the idea of looking for our own agency. The idea is compelling enough and it can be driven forward. There is so much more to discover and to research. The most beautiful part about that is that we can share and interchange our experiences due to differences and due to the fact that we come from almost similar but still very different backgrounds. There is plenty of place to think and to discuss.’

‘For me personally, and this is a very short way of saying this: “As far as there’s pain, the show must go on!”‘

SAODAT ISMAILOVA, 18 000 Worlds, 21.1 t/m 4.6.2023

Vlada Predelina

is an artist researching the role of tacit knowledge systems of women as a sustaining force in relation to land and colonial expansion through gatherings around a particular medium as a focus to bring out intimate discussions and situated histories