Bodies in disarray – Christina Charles & W.E.B. Du Bois

In the early 20th century, sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois coined the theory of double consciousness, in his case the realisation of being Black and American at the same time. This theory of identity friction, of being at once similar and different, has resonated with various marginalised groups in society, including the queer community. Artist Christina Quarles created drawings to a text by Du Bois at the request of Afterall Books.

[answer ] ‘It is a peculiar sensation, this double consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul through the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.’

– W.E.B. Du Bois, Of Our Spiritual Strivings, 1903.

At the turn from the 19th to the 20th century, Black American sociologist, historian, and political activist W.E.B. Du Bois published The Souls of Black Folk, a collection of 14 essays that is still considered a seminal body of work in African American writing. At the heart of the work is the notion of double consciousness, or the condition of being simultaneously American and Black; of having two distinct yet inseparable identities that are embodied and performed by the same person. Since then, the capacious notion of the double consciousness has been utilised to describe the dynamics of gender, sexuality, race, and colonialism. It encapsulates the internal conflict experienced by subordinated groups or individuals in their strive to express their identity from within, while having to reckon with how they are seen from without through the eyes of the dominant party.

Writing about double consciousness, Du Bois noted that despite it being ‘a peculiar sensation’, it was also a ‘gift of second sight’ that could empower the individual with a deeper understanding of themselves and the social realm, consequently enabling them to take impactful political action. While being assigned fixed categories can lead to marginalisation, specific modes of identification can be strategically wielded to build alliances and gain visibility within hegemonic political and social spheres.

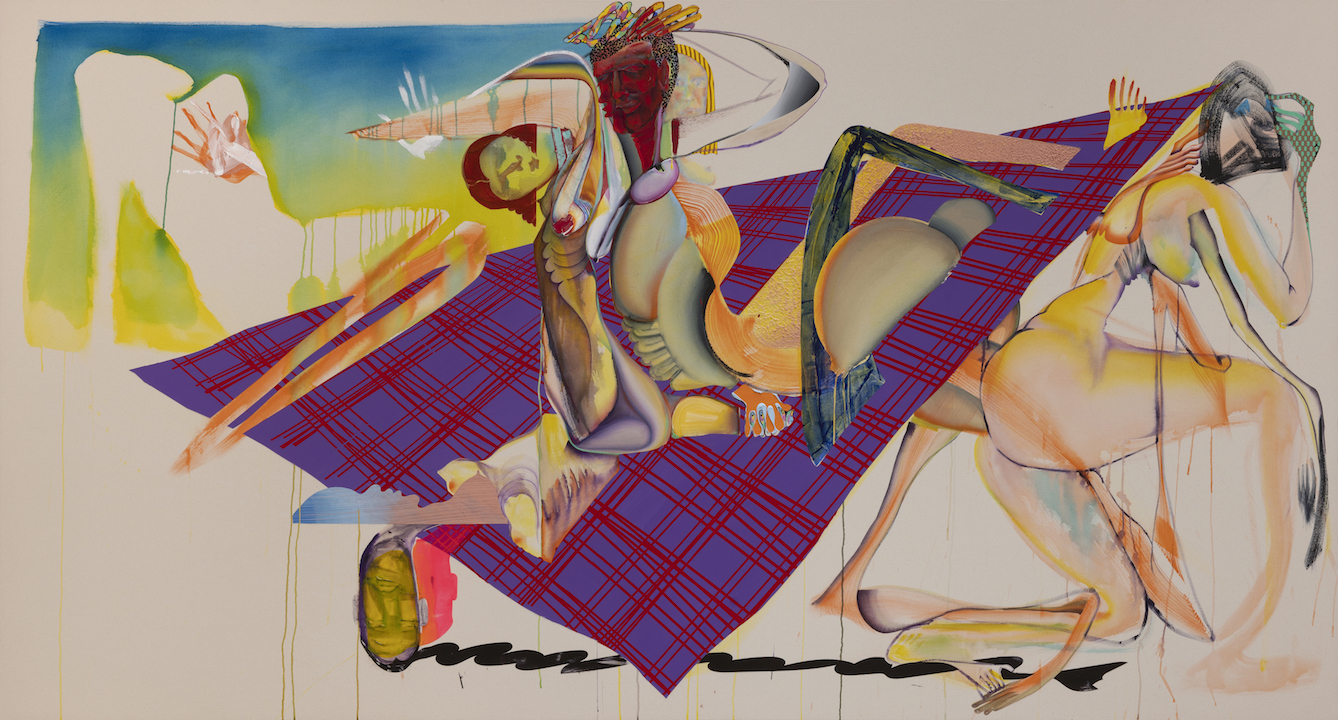

Christina Quarles, 'Had a Gud Time Now (Who Could Say)', 2021, acrylic on canvas, 177,8 x 330,2 cm. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Pilar Corrias, London

Recently, the first chapter of Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk, titled ‘Of Our Spiritual Savings’, has been republished by Afterall Books. As part of their ‘Two Works’ series, in which the work of a visual artist is paired with a text by an influential thinker, they have asked artist Christina Quarles to create drawings to Du Bois’ words.

‘I find that the central focus of my practice is still very much in line with Du Bois’ understanding of racial, political, and physical boundaries’

At last year’s Venice Biennale, Quarles presented six new large-scale paintings, each depicting numerous vividly-coloured, but hardly discernible human figures interacting chaotically. Her bodies recline, intertwine, contort, and even step over one another. It is not always clear where one ends and the other begins, whether they are pushing each other away, or pulling closer together. Sometimes they appear flattened, or as hardly more than a faintly coloured outline, and at other times they appear too abundant for their own good, as if they have been turned inside out or made to burst through their skin, with brushstrokes resembling tendons or rib cages. They are often resting on or further bisected by the patterned perspectival planes worked into the scene. The figures occupy all the width and breadth offered by the canvas, dynamically unravelling up to its very edges, threatening to tumble over into the viewer’s three-dimensional reality. All these characteristics refer to how our surrounding environments impinge on our corporeality and the production of subjectivity.

On her website, the Los Angeles-based artist introduces herself as a queer cis-woman born to a black father and a white mother. This dual identification of having Black ancestry and fair skin can be considered as Quarles’ double consciousness, which also lies at the heart of her artistic practice. The artist describes her dual identity as a contradictory state of being that results in her place always being her ‘displace’. Her signature polymorphous bodies in disarray are not only reflective of her daily experience with ambiguity, but work to dismantle any assumptions that subjectivity can ever be something fixed or completely legible by outsiders.

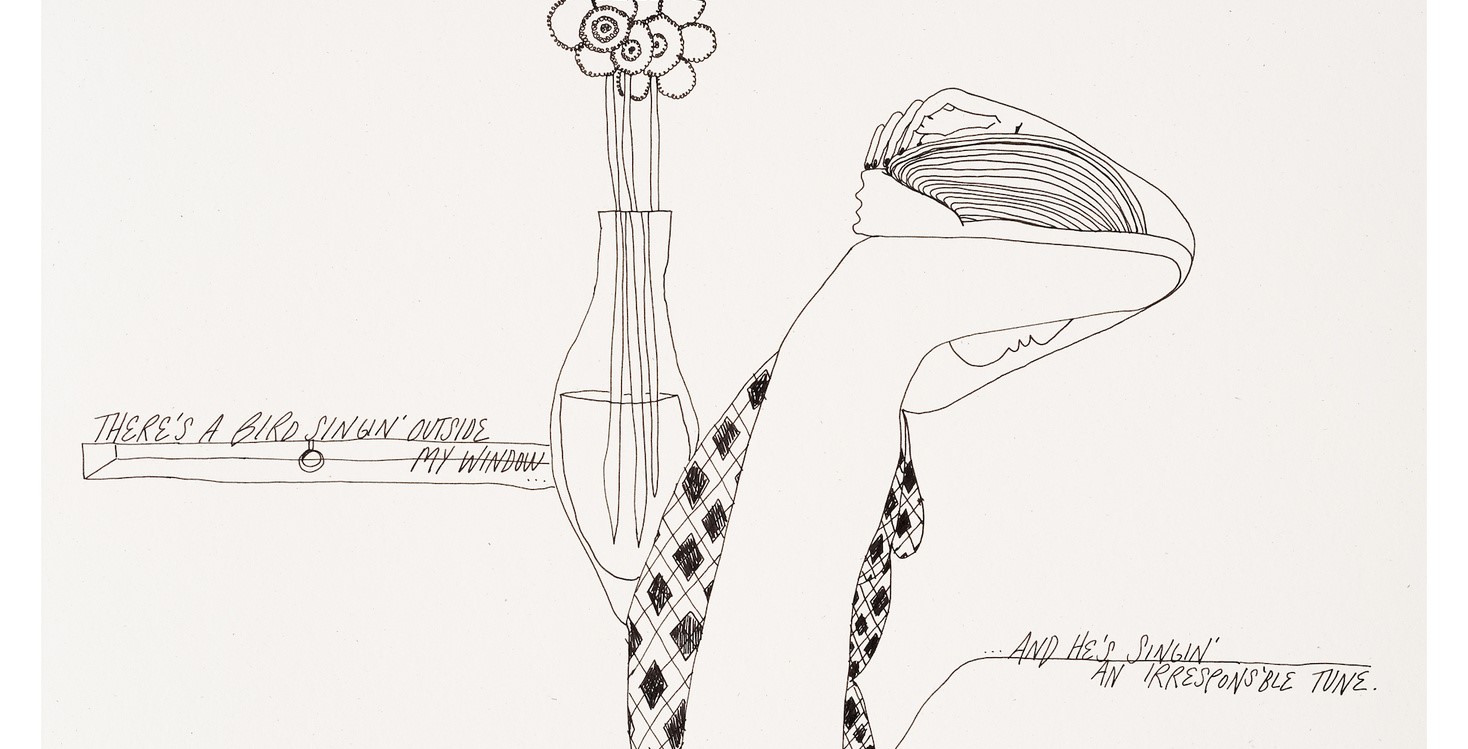

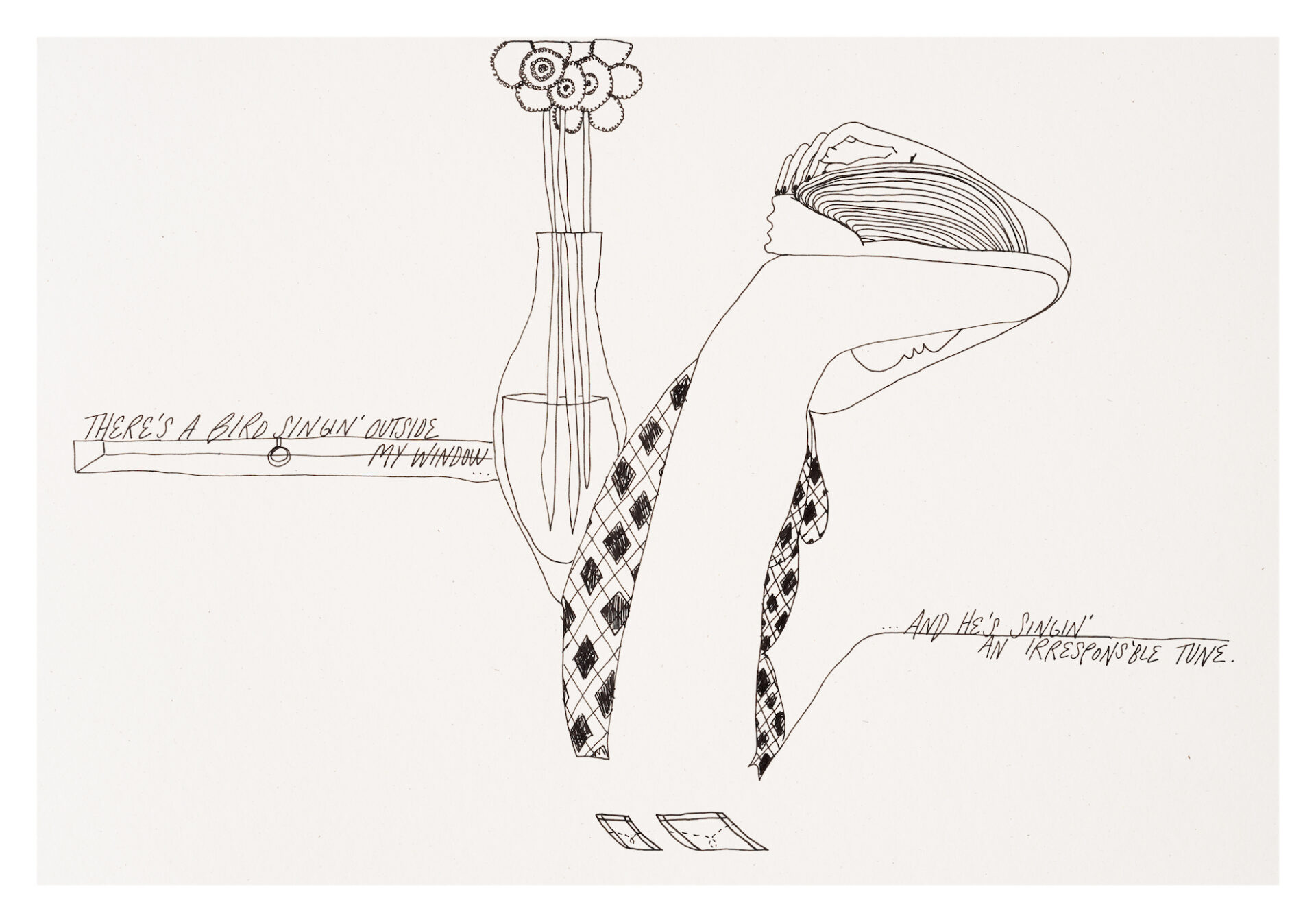

Christina Quarles, 'Irrespons'ble Tune', 2021, ink on paper, 33 x 48,3 cm. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Pilar Corrias, London

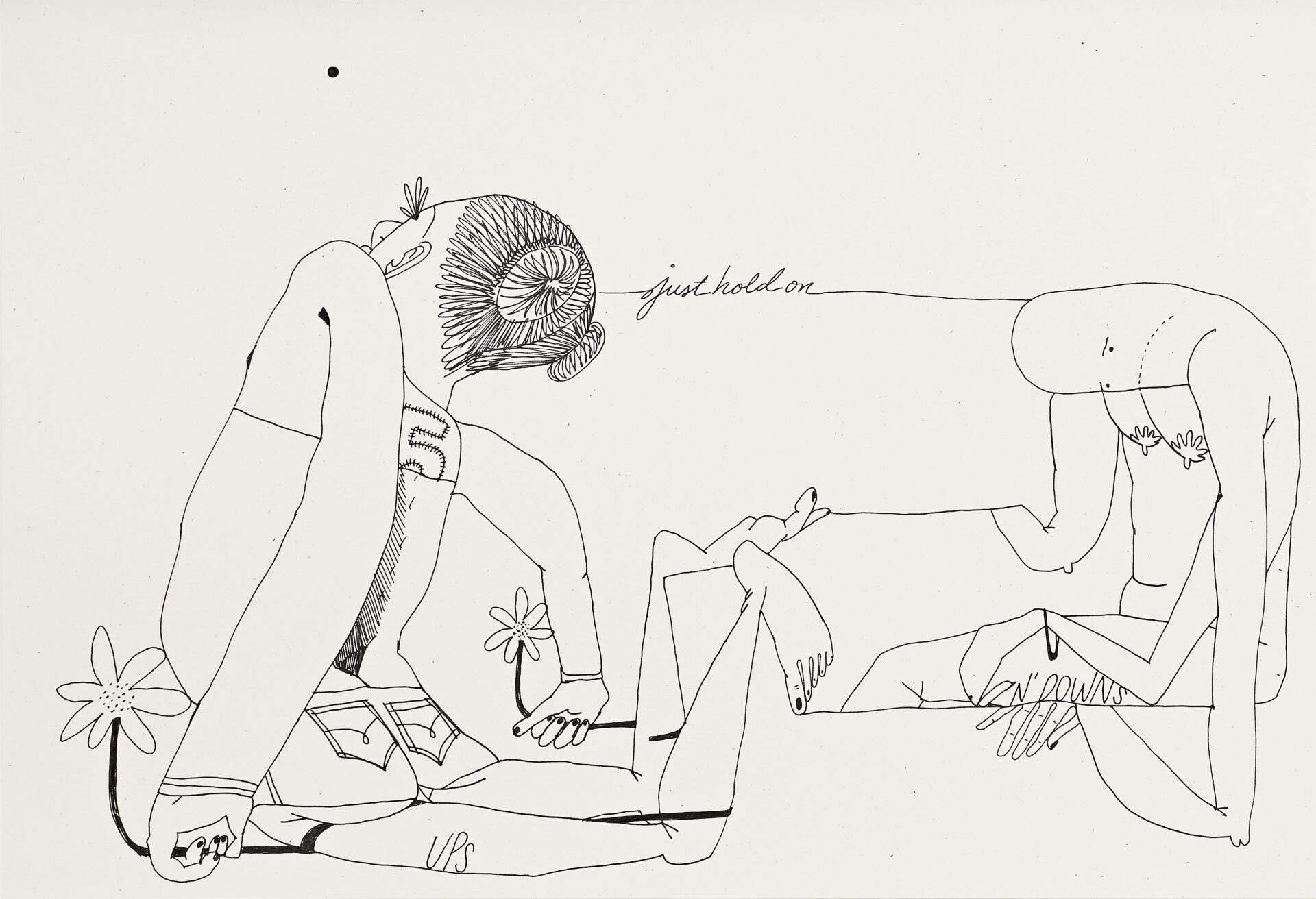

Christina Quarles, 'Ups N' Downs, 2021, ink on paper, 33 x 48,3 cm. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Pilar Corrias, London

Now, Quarles’ fragmented bodies sit comfortably with Du Bois’ eponymously-titled essay, originally published in 1903 (and published in an earlier version, 1897). It is a fitting pairing, considering that in a sense they are old acquaintances. Quarles: ‘I first encountered Du Bois’ Of Our Spiritual Strivings in highschool and felt that it described an experience I had long struggled to name. After highschool, I wasn’t certain if I was ready to express these ideas through my art, so I double majored in Philosophy. For my undergraduate thesis I wrote about critical race theory and multiply-situated racial identities, using my own biography as a point of reference.’ She continues: ‘As an artist, these themes continue to be very present in my work and in my interests. I find that the central focus of my practice is still very much in line with Du Bois’ understanding of racial, political, and physical boundaries.’

Christina Quarles, 'This Isn't 'Bout Yew', 2021, ink on paper, 33 x 48,3 cm. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Pilar Corrias, London

In the publication, Du Bois’ linguistic articulation of double consciousness is followed by Quarles’ series of line drawings in black ink against a background of speckled organic paper. As opposed to the biennial exhibition setting, the book offers a more intimate experience of the artist’s work. As opposed to the large-scale visually explosive paintings that I shuffle past as part of the crowds in Venice, the drawings in the publication are small, monochromatic illustrations that I can hold in my hand, look at up close, flip through, and choose to return to. The disjointed and incomplete bodies that distinguish themselves as Quarles’ handiwork make a reappearance here, and provide a kind of visual meditation on the written work. The poignant question – ‘How does it feel to be a problem?’ – which Du Bois poses among his opening lines, resurfaces in one of the illustrations in which it seems that the figure uttering the question physically burdens the receiver, the words appear to be weighing down on the latter’s shoulders.

The drawings show figures bent and twisted into impossible positions, mid-transformation or flattened and folded onto themselves

Quarles revealed that for this project she listened to an audio version of Du Bois’ essay while drawing. ‘I typically listen to music or watch TV, and weave what I overhear into the drawn text,’ she explains. I interpret this as one of the ways in which external and mental spaces are made to meet and mingle on canvas or paper. The images attest to the contemporary resonance of Du Bois’ endeavour; what was written over a hundred years ago, is being interpreted and translated into visual form by an individual whose daily reality is indeed a form of double consciousness.

The ultimate outcome is a conversation between thinker and artist across space and time, in book form. The drawings show figures bent and twisted into impossible positions, mid-transformation or flattened and folded onto themselves, blank-faced torsos, and disconnected limbs, such as a pair of feet treading on a flowerbed. It is difficult to describe with precision the actions happening and the way in which the bodies move in and out of imaginary planes and illusory spaces. Even after having looked at them at length, a lot is left up to the viewer’s interpretation and any decipherment stays tentative. Much in the same way that it is impossible to represent subjectivity in its totality, total legibility remains elusive here.

A longer, translated version of this text can be found in Metropolis M No 2-2023 Navigator(out now)

Manuela Zammit

is a writer and researcher from Malta