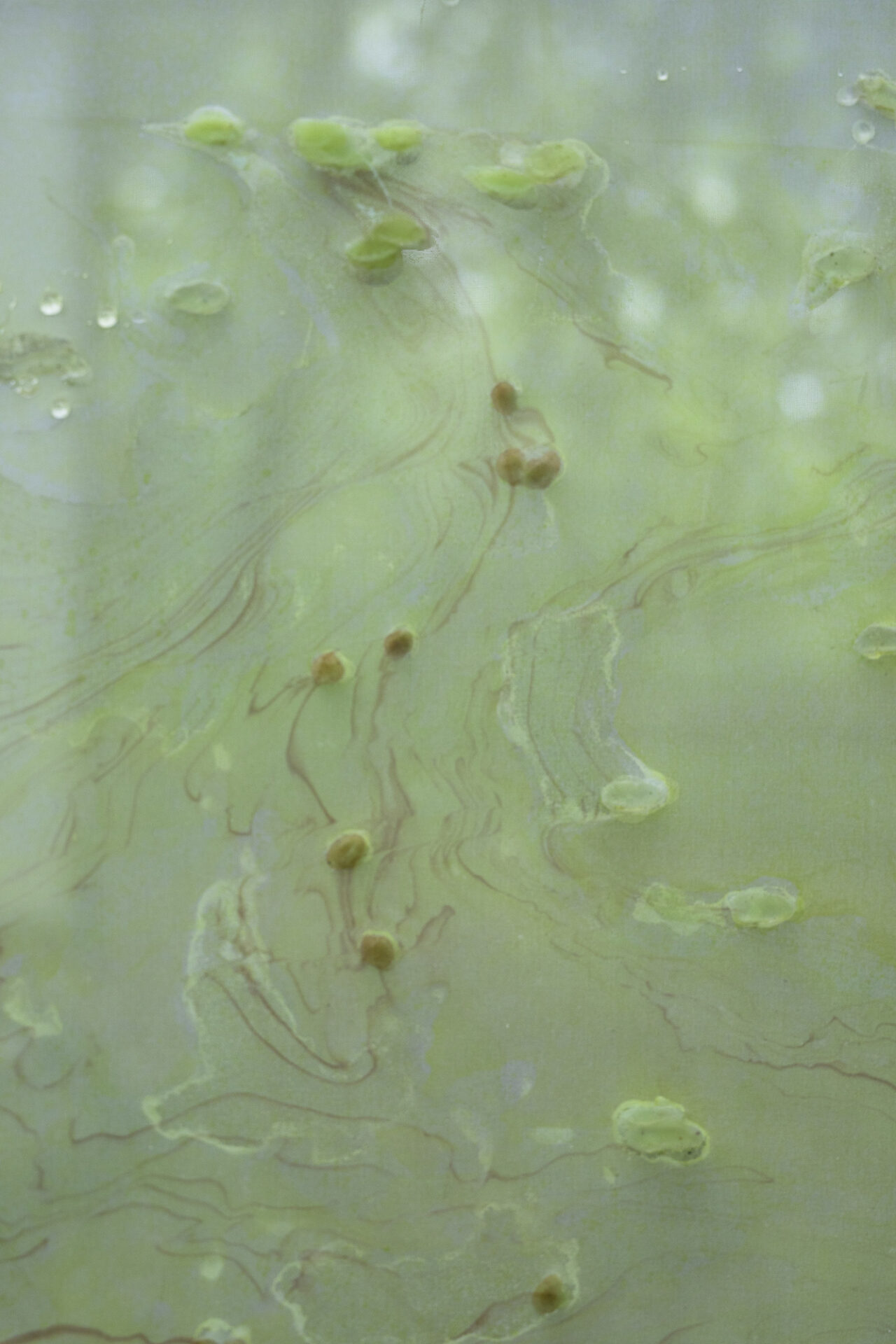

Alma Heikkilä: coadapted with, 2023. © HAM/Helsinki Biennial/Kirsi Halkola

Positive contamination: on this year’s Helsinki Biennale

This year’s edition of the Helsinki Biennale wants to offer agency to nonhuman entities, be they natural or technological in nature. The works are spread around the island of Vallisaari and its old gunpowder cellars, facing the challenge and opportunity to work with their surroundings. Eliisa Loukola visits Vallisaari and selects some site-specific works.

The second edition of the Helsinki Biennale, New Directions May Emerge takes place again in the historic Vallisaari, one of over 300 islands on the Helsinki archipelago, a 20-minute ferry ride from the market square at the heart of Helsinki. Even at such a short distance, Vallisaari feels beautifully remote, quiet (with the expectation of its sheep making noise in their enclosements around the island), a stark difference to the market square, filled with tourists, seagulls and the smell of fried fish.

Materia Medica of Islands, 2023, Helsinki Biennial 12.6.-17.9.2023, Vallisaari, Helsinki, Photo: © HAM/Helsinki Biennial/Sonja Hyytiäinen

Vallisaari was used during the Russian rule in Finland as a military base, and after Finlands independence in 1917, it remained in use as a military island, and has only opened to the public in 2016, after been left by the army in 2008. The Russian soldiers located on the island brought along a wide array of flora and fauna not found in the wild in other parts of Finland, including moths. Due to the island’s seclusion, these have created unique ecosystem, some of which is highlighted in Lotta Petronella’s Materia Medica of the Islands (2023), which I will discuss later.

Due to the island’s seclusion, these have created unique ecosystem, some of which is highlighted in Lotta Petronella’s Materia Medica of the Islands (2023)

In Vallisaari, you can encounter 23 of the biennial’s 30 artworks, some works and events held in the exhibition hall of HAM (Helsinki Art Museum), others taking you around the city. Most of the works on the island are underground, in the cool and rough gunpowder cellars built in the early 1800s by the Russian army.

Curator Joasia Krysa leads the thematic core of the biennial through the American anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsings book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (2015), from which its title New Directions May Emerge is adopted. It follows Lowenhaupt Tsings proposed learning from (the art of) ‘noticing´ at its core, bringing focus to contamination, regeneration and agency as its central themes. Krysa, who works at the crossroads of art and technology, is a curator and researcher that has previously worked on the curating team of Documenta 13, held in Kassel, Germany and was one of the curators of the Liverpool Biennial in 2016.

Vallisaari sits on the Baltic Sea, one of the most polluted seas in the world, and its terrifying state (largely due to unregulated industrialism on its shores) is directly discussed in many of the works selected for the biennial. Most of these themes were discussed extensively in the first edition of the biennial, yet it still manages to bring something new to these topics. However, the works do seem to be turning a little more universalistic in nature, as the newness and urgency to deal with Vallisaari itself (one of the highlights of the first edition) takes a backseat. Asking for and proposing new ways to be with the world, possibly through a kind of positive contamination, as Krysa puts it, the biennial wants to offer agency to nonhuman entities, be they natural or technological in nature. The works are spread around the island’s unique nature and its old gunpowder cellars, facing the challenge and opportunity to work with their surroundings.

Compared to the first edition of the biennale, the works seem to be turning a little more universalistic in nature, as the newness and urgency to deal with Vallisaari itself (one of the highlights of the first edition) takes a backseat

As these challenges become apparent, I wonder whether the next edition should take place in another part of Helsinki. Continuing to hold the biennial on Vallisaari runs the risk of the island becoming a gimmick, rather than an opportunity for critical artistic reflection of the city’s history and current socio-political state. Perhaps the biennial could itself positively contaminate and activate discussions on the histories of different groups, neighborhoods and their changes on location throughout the city. Doing this, perhaps, was the great success of the first Vallisaari based biennial. Despite these challenges, the Helsinki biennial offers a thematically coherent show that gently suggests alternative ways of considering the world.

I have chosen to highlight some of the works shown at the biennial, that feel to successfully take both the curator Krysas interpretation of Lowenhaupt Tsings art of ‘noticing’ as well as brought something new into the understanding of the biennial itself. They, beside being personal highlights, all provide a site-specific approach to dealing with the island of Vallisaari, yet still manage to convey something greater than what has happened inside its shoreline.

Tuula Närhinen

Tuula Närhinen presents two art works at the biennial, one at HAM, the other one in Vallisaari, both discussing pollution and littering in water, going from Thames to the Baltic Sea, one of the most polluted seas in the world. Working from Harakka Island, another of the many islands on the Helsinki archipelago, Närhinen is directly involved with, and bears witness to the sea and its changes, which is hugely influential to her work. This feels intimate, almost sad in Plastic Horizon (2019-2023), where she presents her collection of plastic found on the shores of Helsinki, collected over the years, starting from 2008.

Tuula Närhinen: The Plastic Horizon, 2019-2023, © HAM/Helsinki Biennial/Sonja Hyytiäinen

Tuula Närhinen, Deep Time Deposits: Tidal Impressions of the River Thames, 2020. © HAM/Helsinki Biennial/Kirsi Halkola

Here, stretching through one of the dramatically lit tunnels of the many gunpowder cellars found on Vallisaari, the plastic is arranged into a beautiful gradient of colours, where q-tips and candy wrappers pile on themselves and paint a harrowing image of human carelessness. Närhinen describes digging up the plastic from the beaches, and later washing said trash, to let their artificial colours shine, in an act full of care and worry. Such care is also seen on the gentle, quiet presentation of the plastics, that are lit up and set up running on a shelf along the hallway, almost seem like artifacts of a soon to be lost civilization.

In combination with her work Deep Time Deposits: Tidal Impressions of the River Thames (2020), found on the mainland at HAM, Närhinen manages to draw parallels to the mistreatment of the two bodies of water. Deep Time Deposits consists of an archive of material, mud and found objects found from the riverbanks, as well as cyanotypes made with the found material. This archive is presented in a way that feels much more sterile than Plastic Horizon, yet still coveys the same careful sadness.

Lotta Petronella

Lotta Petronella, together with chef and forager Sami Tallberg, and composer and performer Lou Nou, have turned one of the cottages found on Vallisaari into a little ‘pharmacy’ called Materia Media of Islands (2023). Here, healing singing and nutrition create a dialogue with the flora and fauna of Vallisaari. The pharmacy is created in the footsteps of Ilma Lindgreen, who in 1914 began a fight for equal rights to roam and forage freely in Finlands forests. This legal battle took years but resulted in implication of ‘every mans right’, a right for free personal use of nature. The pharmacy is filled with extractions of the plants found on Vallisaari, many of which have been brought on by Russian soldiers during their time on the island. Alongside these plants, there’s some hundred moths that are a part of the island’s unique nature, here displayed as tarot-cards. The space is athmosphered by a choir of laments, done in collaboration with Lou Nou, that give the space a historic, almost otherworldly feel. The pharmacy is activated through performances a few times during the biennial.

Materia Medica of Islands, 2023, Helsinki Biennial 12.6.-17.9.2023, Vallisaari, Helsinki, Photo: © HAM/Helsinki Biennial/Sonja Hyytiäinen

Remedies/Rohdot (Sasha Huber and Petri Saarikko)

Sanctuary, mist (2023), made by Remedies/Rohdot, a collaboration between Sasha Huber and Petri Saarikko, is one of the most memorable works created for the Biennial. One of the sweetwater ponds on Vallisaari is making mist. On the day of my visit, it is licking the surface of near still pond, disappearing into the tree line. The pond has been dug by the Russian army to be used as a well, and later created its own ecosystem. The installation on the pond is accompanied by a poem, that raises the question about seeing nature not just as a backdrop for human life, rather as an entity itself. The work asks the viewer to question its sculpturality, whether the work itself is a part of the landscape, or rather something else.

Remedies/Rohdot: Sasha Huber & Petri Saarikko, Sanctuary, mist, 2023, Helsinki Biennial 12.6.-17.9.2023, Vallisaari, Helsinki, Photo © HAM/Helsinki Biennial/Kirsi Halkola

Alma Heikkilä

Another work successfully taking in the island’s nature is Alma Heikkilä’s coadapted with, in which fabric is stretched to form a cube, encapsulating a sculpture within itself, while allowing the nature to flow in an out off the created space. The semi see-through fabric is painted with green paint, the pigment of which is created with plants found on Vallisaari. Silicone mushrooms are growing into its inside, blending into the natural shadows that are bleeding into the installation, making you question where indeed the work ends and the surrounding woods begins.

Alma Heikkilä: coadapted with, 2023. © HAM/Helsinki Biennial/Kirsi Halkola

Heikkilä plays with the natures direct effect on the work, the pigment on the fabric mixing with rainwater, gradually tinting the plaster sculpture in the middle of the created space, and listing sunlight as one of the materials of the work. While some of the other works of the biennial seem to struggle with the thematic core of the show, coadapted with subtly contaminates, or perhaps lets itself be contaminated by the island, yet in this encounter of different phenomena manages to create something new.

New Directions May Emerge can be visited until September 17th, 2023

Eliisa Loukola