Avenue des Mémoires

Avenue des Mémoires

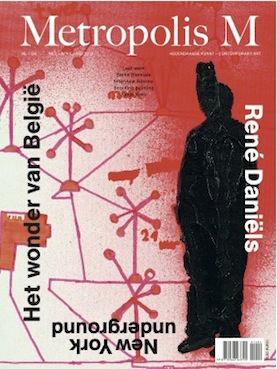

René Daniëls and the Art of Memory

With major exhibitions in Madrid and Eindhoven, the highly self-reflective oeuvre of René Daniëls is once again attracting attention. The Eindhoven exhibition offers an opportunity for a review of Daniëls’ late work, which he produced early in his life, due to afterward suffered a stroke. Of the tens of thousands of works of art that I have seen, I have forgotten a lot, but not those of René Daniëls. A visit to his retrospective exhibition at the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid was consequently a feast of recognition. What a joy to stand eye to eye once again with the colourful, intriguing paintings that have given so much inspiration, and what a pleasure to discover drawings that I had never seen before. In the high-ceilinged galleries of Palacio de Velázquez, the 19th-century museum annex at the Parque del Retiro, the works were shown to their best advantage ever. There couldn’t be a better setting for them than here, with star-shaped partitions set up according to a design the artist himself had made back in 1985. The installation inspired some speculations about the connection between Daniëls’ painting and the inimitable paths of memory. René Daniëls’ work has countless references to memory. Some of the titles refer to reviving and accessing memories (De revue passeren (Passing in Revue), 1982), others to forgetting (Memoires van een vergeetal (Memoires of a Forgetful Person), 1987). The paintings in the Lentebloesem (Spring Blossom, 1987) series evoke associations with centuries-old memorization techniques. Not that memory is an explicit theme – it is sooner the case that the way our brains process information offers an analogy for Daniëls’ conceptual approach to painting. How does an image originate? What is the relationship between sign and significance? How does image relate to language? In his painterly investigations, Daniëls charted places where words change into images and images change into words. That is precisely where the parallels with mnemonics become visible.The accuracy of our memories is something we cannot rely on. In Memoires van een vergeetal (Memoires of a Forgetful Person, 1986), an exhibition gallery is presented with white paintings. Above them float yellow planes, like after-images, or memories that have completely detached themselves from the original works of art. From the moment we take on new information, our memories already begin to falter. According to writer Joshua Foer, after an hour, we have forgotten about half of what we have seen.1 Completely forgetting something, however, is just as difficult as remembering it well. A 1987 painting with the same title shows two façades with words on them, which are difficult to read. We expect a word such as ‘HOTEL’ – not illogical in terms of identifying buildings – but our expectation is frustrated. With a certain amount of patience, one can decipher the word ‘PORTE’, applied once from left to right and again over the top, mirrored from right to left. The resulting dyslexic confusion shows that a memory can be unclear and incomplete, but also that total forgetting does not exist. We are never entirely sure whether the information we can no longer access has been definitively erased from our memories or not.The oldest metaphor for memory is perhaps the wax tablet, used in antiquity to record information. The inscription in the layer of wax stands for remembering something, while wiping the surface clean means forgetting it. Erasing facts creates a tabula rasa, and we start over again with a clean slate, as it were. But how clean is that slate? Is the knowledge stored in the past really gone? In paintings such as Het Romeinse wastafeltje (The Roman Wax Slate, 1983) and Ondergronds verbonden (Connected Underground, 1984), the presentation is largely covered up by a semitransparent layer of red paint. What was painted underneath still shines through the surface. To put it differently, what no longer makes up part of our readily accessible knowledge remains latently present, living a slumbering existence. We always drag our memories around with us, even when we can no longer clearly recall the images. They give form to (and are formed by) the new information that is forever uninterruptedly coming our way. We remember images better than words. In recognition research done in the 1970s, study groups were shown an impossible-to-digest number ten thousand photographs, for only half a second each. Later, they were able to recall more than eighty percent of the images.2 We register a lot of information without trying, a form of unconscious recall referred to as ‘priming’. Beneath the surface of our conscious thoughts lurks an expansive world of impressions we are hardly even aware of. In his work, Daniëls repeatedly sought access to this subconscious world. One gateway to this domain is écriture automatique, a form of writing that eliminates conscious reasoning and allows every intervention to run its course, a system enthusiastically propagated by Guillaume Apollinaire. What the Frenchman did with words is what Daniëls tried to do with images, producing such puzzling paintings as De revue passeren (Passing in Revue, 1982). The relationship between memory and place forms the core of the classical art of mnemonics. Legend has it that some 2500 years ago, the ars memoria was discovered by Simonides of Keos in the ruins of a collapsed dining hall. When the poet closed his eyes and turned his thoughts to the room prior to the disaster, to his astonishment, he discovered that he was able to remember exactly where every guest had been sitting during the dinner. It appears that we are better able to remember information when we make use of our sense of spatial orientation as we store it away. The trick is to imagine the information in a space that we know very well. Then all we have to do is to move through that space in our minds in order to recollect the facts, one by one, place by place. This is mnemonics of the loci, recorded in the Retorica ad Herrenium (82 BC), which allowed Roman senators to remember long speeches, and which was used by medieval scholars to learn entire books by heart.3 An echo of this memorization technique still echoes in the word ‘topic’, which comes from the Greek topos, which means ‘place’. ‘In the first place’ is another expression we have inherited from mnemonics.4In March, 1987, René Daniëls moved from Eindhoven to Amsterdam, into a studio and residence on the Geldersekade in the city centre. For two years, the art exhibition had been his most important subject matter, in perspective representations of exhibition galleries in the shape of a bow tie. In Amsterdam, this motif made way for a new figure, a map or blueprint of channels or canals that can also be read as schematic trees. His stepping away from perspective and introducing of the map as the most important mode of representation (already introduced in paintings such as Plattegrond (Map), from 1986) formed the cornerstone of a group of six paintings and 15 drawings, known under the collective title of Lentebloesem (Spring Blossom). It was in these works that Daniëls re-examined his position toward the work he had completed to date, and in relation to such artists as René Magritte and Vincent van Gogh. In these painterly memory exercises, the connection between memory and location plays an important role. In Kades-Kaden (Quay-Quays, 1987), the first work of that series, Daniëls took a number of titles of his paintings and exhibitions and arranged them on an imaginary map of his total oeuvre. The map has the shape of branching canals on both sides of a central axis. Underneath is written ‘De revue [pass]eren’.5 With classic mnemonics in mind, one could call it a memory chart. The titles are loosely grouped along the quays of the canals, rather like goods arranged by kind in storage warehouses (the warehouse is a common metaphor for memory).6 In between the titles, we read ‘ROKIN’ and ‘WARMOES’, names of streets in the immediate vicinity of Daniëls’ new home, and such ambiguous terms as ‘GEESTGROND’ (spirit ground/sandy soil between the dunes and the polder), that we recognize from geography classes. It is as if, now that the artist has moved, he is once again reviewing all of the works he has completed and, at the same time, is giving them a place in his new living environment.7 With a little good will, one can also recognize a cross-section of the human brain in this map. At the place where the hippocampus, the part of the brain that plays an important role in spatial navigation, should be, we read, ‘fresh transportation’. A painted-out section of white paint, in the shape of a pipe, more or less coincides with the Broca’s area of the brain, where our motor centre for speech is located. Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe automatically comes to mind. If Kades-Kaden is like a map of the memory, in other paintings with the same motif, the recapitulation of previously completed works results in a kind of tree of life. Titles are revealed along the branches, like fresh blossoms. Blossoms as a symbol for young life is not without precedent in the art of painting. Daniëls had certainly seen Van Gogh’s Almond Blossom (1890) in the Van Gogh Museum collection, a painting made in Saint-Rémy for his newborn nephew, who had been named after him.8 Several critics have noted the visual connection between Daniëls’ Lentebloesem and Van Gogh’s composition of canvas-filling branches against a clear blue sky. The metamorphosis of the basic figure, from a bird’s eye view of a system of canals into a side view of a blossoming tree, illustrates the self-generating capacities of René Daniëls’ painting, in which the new continually evolved from a slight alteration to what preceded it.In one of the Lentebloesem paintings, the titles have been replaced by words in Swahili. Daniëls took the words from a textbook called Teach Yourself Swahili. For someone who does not understand this East African language, the words are not only incomprehensible, but also impossible to remember, because they cannot be connected in an arrangement that makes any sense. The words themselves, however, are not meaningless. Many terms are about place designations (Dar es Salaam is a city in Tanzania, mahali pazuri means ‘a beautiful place’) or about bearing fruit (machungwa yaliiva means ‘the oranges are ripe’ and zaa matunda jaa can be translated as ‘fruit in abundance’).9 We learn foreign languages by endlessly repeating words and their conjugations. People who imprint these lists onto their memories on the basis of sound and rhythm are able to retain that knowledge for a surprisingly long time.As a whole, the Lentebloesem series reflects the slipping away of time, the rhythm of day and night and the cycles of the seasons. The final painting, completed before December of 1987, when the artist suffered a cerebral aneurysm, is night-time blue. Here, the titles have been replaced by descriptions of places and times. Some of these come together: ‘January’ and ‘February’ are names of months, but they are also names of the so-called Calendar Warehouses along the Achtergracht, not far from where Daniëls was living at the time. ‘Places where changes in a person’s life are documented’ and ‘places, buildings where changes in perspective can be obtained’ can be associated with public institutions, such as hospitals and museums, which are identified on every city map. There is also a bicycle hanging in the branches. Like a pop-up traffic sign, the two-wheeler symbolizes moving through the city, which is at the same time a moving back in time. In the Lentebloesem paintings, not only are the connections between name and place, between word and image revealed, but so too is the connection between lasting memories and perpetual renewal. The paintings are like memoranda of life itself. Memory perceived as an archive or warehouse, where we can retrieve knowledge we have previously acquired and store new information at will, is a metaphor that does not do justice to physical reality. Our memories are bound together with one another in a web of associations. The brain is made up of some hundred million neurons, each of which can process five to ten thousand synaptic connections. ‘A memory, at the most fundamental physiological level, is a pattern of connections between those neurons,’ writes Joshua Foer. ‘Every sensation that we remember, every thought we think, transforms our brains by altering the connections within that vast network.’10 René Daniëls’ underground connections, branching channels and budding blossoms reflect this changeability better than the rather static metaphor of the storage archive. Since 2006-2007, some 20 years after his stroke, René Daniëls is again working regularly, which suggests some improvement in his recovery. Although curator Ronald Groenenboom writes in the catalogue that these new paintings are just as layered and as humorous as those Daniëls produced before 1988, they are not the same. The artist still suffers from aphasia and has difficulty using his right arm. He now draws with his left hand, with felt-tipped pens and spray cans, in smaller formats. Most of these canvasses are black-on-white, with only one or two colours (fire red, bottle green). We recognize motifs from his earlier work: the man with the erected beard; the movie camera; the bow tie. New motifs are appearing, including a silhouette of a remote control device, for example, and something that looks like the moon circling the Earth, a kind of new visual signature. The images sometimes appear to be random arrangements of loose fragments, like the letters and figures that Daniëls makes to clarify what he is trying to say during conversations. Sometimes they look like brand new links between trusted motifs, united in wordless silence.Dominic van den Boogerd is director of De Ateliers, AmsterdamNotes1. Joshua Foer, Moonwalking with Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything (New York: Penguin, 2011), p. 24.2. Ibid, p. 27.3. Ibid, pp. 9, 94.4. Ibid, p. 123.5. Because the letters ‘p-a-s-s’ have been covered up by white paint, the title reads ‘De revue ….eren’, or ‘honour what we look back on’.6. Another metaphor is the archive. In the 1987 drawing, Kades-Kaden, the facades of the warehouses have been transformed into desk drawers that refuse to relinquish their contents.7. In a 1987 untitled drawing, warehouses named after movements in art history (De Stijl) and architectural monuments (Walvis) are flanked by ‘Noorweegen’, a warehouse right next to Daniëls’ own home at the time. The ambiguous relationship between name and place is one of the underlying themes of the work from 1987. 8. In her thesis on Daniëls’ Lentebloesem, (VU University, Amsterdam, 2006) Saskia van Kampen mentions a postcard of Van Gogh’s Almond Blossom that was reworked by Daniëls and sent to gallery owner Paul Andriesse.9. Ibid, based on Van Kampen’s Swahili-Dutch translation.10. op. cit., Foer, p. 33. See note 1.

Dominic van den Boogerd