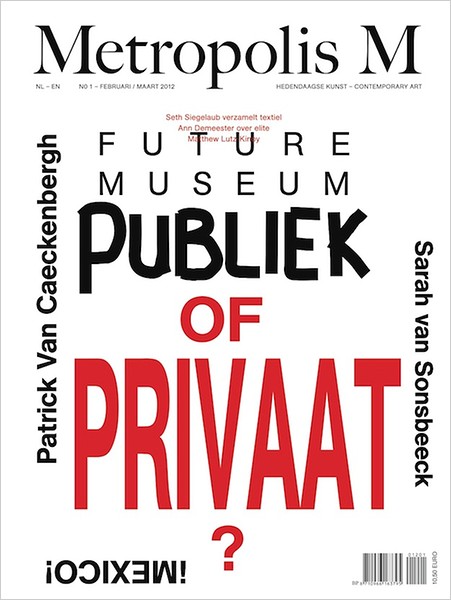

Farmed out to the public

Farmed out to the public

The Sammlung Falckenberg

The Sammlung Falckenberg is seen as a classic example of a public-private collaboration. The collection of Harald Falckenberg came under the wing of the Deichtorhallen in Hamburg in 2011. Johannes Wendland spoke to those involved and assessed how things are going.As elsewhere in the world, in Germany, there is no question of an easy relationship between private collectors and public museums. As a result of the rise in private wealth in recent decennia, exceptionally large collections of art have evolved outside the museums. This puts the collections of museums and other art institutions under pressure, because, with their markedly shrinking acquisitions budgets (if they still have budgets at all), they are no longer in a position to build comparable contemporary art collections of their own.As a result, there is a lot of beating at the doors of major private collections. Long-term loans, special foundations and donations are highly sought after. There is a great deal of competition between cities as well, and as a result, a great deal also goes wrong. This was the case, for example, with the collection of Dieter Bock. In 2005, Boch abruptly cancelled his collaboration with the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt. All of a sudden, an important institute was faced with ruin because it no longer had access to a significant portion of the works it exhibited. The real estate investor simply auctioned off his collection, which had increased considerably in status and value thanks to being exhibited at the museum.A different case, which resulted in tremendous publicity for totally different reasons, was the collection of Friedrich Christian Flick, which has been on permanent loan at the Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin. Several cities, including Zurich, had refused to take on the collection of the industrialist family, which had collaborated with the Nazi regime. But it was in the German capital city, of all places, that they saw no offence in presenting the rapidly assembled Flick collection, which at the time the loan was being negotiated was still refusing to contribute to the foundation for reparations for people who had been subjected to forced labour during the Nazi period.In Hamburg, for a year now, we have been able to view a very different example of a public-private collaboration, notably that between Harald Falckenberg and the Deichtorhallen. Thanks to a recently decided contract, the renowned art institute will have access until 2023 to both Falckenberg’s celebrated collection and a second exhibition location, the stunningly renovated Phoenix-Hallen in the suburb of Harburg, south of the Elbe, which also belongs to Falckenberg. This deal was the result of a pursuit that took years, because since the 1990s the flourishing art metropolis of Berlin has exercised an irresistible power of attraction over the collector, as it has over other key figures in the Hamburg art scene. Harald Falckenberg is in fact of a completely different calibre than a Dieter Bock or Friedrich Christian Flick. He is not a fickle entrepreneur, with whom people have to accept personal idiosyncrasies for the sake of the art, but the owner of a midsized factory for tank and chemical piping in Hamburg. Falckenberg is moreover not the type of collector to conceal his lack of knowledge behind a stack of bank notes. He has been collecting art for more than 30 years. The spiritual centrepiece of the Sammlung Falckenberg is the Fluxus movement. American art is also well represented, with works by Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, Martha Rosler and more. German heroes in the collection include Martin Kippenberger, Jonathan Meese and John Bock. In 2007, Falckenberg purchased the Phoenix-Hallen in Harburg (where he had already been exhibiting the artworks since 2001), and had the industrial complex built into an exhibition space by the Berlin architect Roger Bundschuh. By 2010, Falckenberg had organized nearly 30 exhibitions in de Phoenix-Hallen, all centred on his own collection and for which he himself served as highly engaged curator. But Falckenberg, now 68 years old, was in search of a more permanent solution. When Berlin eventually backed out after long deliberations with the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz (Falckenberg was dissatisfied with an offer to present his collection at the Hamburger Bahnhof, where it would have to take its place alongside those of local celebrities Erich Marx and Friedrich Christian Flick), Hamburg was able to take the prize.In the deal with the Deichtorhallen, under a Limited Company contract, the city of Hamburg is engaged as a third party. According to the contract, the Deichtorhallen will be able to make use of the Phoenix-Hallen as an exhibition location. There, in addition to the Falckenberg collection, they can also organize other exhibitions. The city pays the Deichtorhallen an extra €500,000 per year for the Phoenix-Hallen, plus €70,000 for two staff members: a curator and an assistant, both employed by the Falckenberg collection. All additional costs made on behalf of the Falckenberg collection are to be covered by the collector.As a result, the Deichtorhallen, which have no collection of their own, now had (in addition to their management of the photography collection of F.C. Gundlach for the Haus der Photographie in the smaller Südhalle) a new collection on permanent loan. ‘For us, this is very important, especially in exchanges with other museums,’ explains Dirk Luckow, director of the Deichtorhallen since 2009. ‘According to our contract, we can make the works in the Falckenberg collection available on loan.’ Now, with their third exhibition space, the Deichtorhallen also have a greater general impact. ‘In September, we had an opening every week. The Phoenix-Hallen also complete the picture in terms of content. Here, we can organize ambitious projects that cannot be presented at the Deichtorhallen, because there we have to focus on attracting a broad public and keep account of our numbers of visitors.’Luckow’s ideal exhibition concept was realized at the end of 2011. In the large space of the Nordhalle, the theme exhibition Wunder attracted large crowds of visitors. Meanwhile, the Südhalle hosted an historic photography exhibition, Eyes on Paris, and at the Phoenix-Hallen, there was Atlas, an exhibition curated by philosopher Georges Didi-Huberman, which investigated the art of the 20th and 21st centuries in the context of the Mnemosyne Atlas, by Aby Warburg. The exhibition originated in collaboration with the Reina Sofia in Madrid and the ZKM in Karlsruhe.For Harald Falckenberg as well, weighing the balance after a year of the new collaboration, things are moving in the right direction. ‘The commercial aspects are relatively easy to hand over, but that is not true of the organizational side of things, the contacts and so on. All that takes much longer,’ as Falckenberg explains. ‘Transport, insurances, catalogues – these were already well arranged. Now we have to arrange new trajectories for them. That does not happen on its own accord.’ Nor is the financial support from the city proportionate to the actual costs. Falckenberg has to cover everything beyond that himself: ‘This year has been decidedly more expensive.’The contract with the Deichtorhallen does not include a clause stipulating the degree to which the works from the Sammlung Falckenberg have to be involved in the exhibitions organized by the Deichtorhallen. An increase in the value of the collection through a museum presentation is for this reason not anticipated, but it is certainly not out of the question. What happens after 2023 is anyone’s guess. Falckenberg wants to remove himself completely from organizing exhibitions as soon as 2013. The city will have to think of some way to keep the collection after the contract expires. The prospects in this regard are not good. Germans are going to have to take serious government budget cuts over the next few years into account. The worse the financial perspectives are for cities and municipalities, the greater the private collectors’ space to manoeuvre, or indeed, to put it in more drastic terms, the potential for extortion.Johannes Wendland is an arts journalist based in Berlin

Johannes Wendland