Ant’s work and beautiful things

Ant’s work and beautiful things

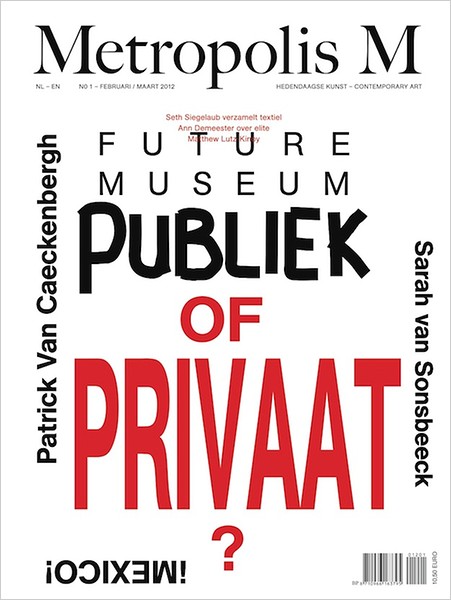

Interview with Seth Siegelaub

Seth Siegelaub, who was one of the key figures in Conceptual Art during the sixties, withdrew from the New York art scene in the early seventies. In relative seclusion, he started collecting textiles – rugs, tapestries, fabrics, embroideries, even hats – from all corners of the world. Soon, part of his extensive collection will be shown in public for the first time, in London.Hard not to start with a cliché. Seth Siegelaub is known for his revolutionary work in showing and promoting Conceptual Art in the sixties and seventies. His gallery, Seth Siegelaub Contemporary Art, which he opened after having worked at SculptureCenter in NY (‘yes, the same institution with the same name today, but then a far more conservative “garden sculpture” set-up’), was only operational from 1964 to 1966. After closing the gallery, (‘it was a boring experience, but probably necessary for my growing up’) he worked as an independent curator – or whatever it was called back then – organizing shows, projects and working closely with artists such as Carl Andre, Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner. For some time now, he has been living in Amsterdam. There, he heads up the Stichting Egress Foundation, in which his passions for contemporary art, textile and critical theory converge.

You mentioned that the gallery was actually called ‘Seth Siegelaub Contemporary Art and Oriental Rugs’. Were these, then, the beginnings of your interest in textiles?

‘Yes, in fact in my archives there is an old sign with that name. For three months at the beginning the gallery I also tried to sell oriental rugs, but I was no better at that than selling art. It was around that time when I started collecting books on carpets. These books were meant to be study material for the rug business.’

And you continued buying books, which evolved into books on textiles.

‘Indeed. But I put all of that aside, and it wasn’t until 20 years later, in the mid 1980s in France, when it began to really take shape. In the late 1960s, I had loaned out the books to the Asia House Gallery in New York, under the care of its first director, Gordon Bailey Washburn. And I totally forgot about it and went about my art world life until 1972-73, when I moved to France.’

You left the art world in 1972. Why?

‘That’s a difficult question. Basically I was interested in other things. I wanted to do something else and I began to get interested in the media, in the theory and practice of newspapers and news agencies. This was partly inspired by the activities of May ’68, the anti-war movement activity, out of picketing and the like. And that is part of the reason why at the end of this period, the projects I did were the Artist’s Contract [a contract specially designed for artists, created in collaboration with the lawyer Robert Projansky in 1971 – ed.] and the USSF [United States Servicemen’s Fund, also in 1971 – ed.] anti-war fundraising projects.’

Did you feel like you were done with the art world?

‘Yes, I felt I was finished with it. Obviously I, or we, were quite fortunate that Leo Castelli, for some reason, had decided to take all the artists on. He made my “job” or my responsibility to the artists a little easier to deal with. Which was an important factor, because I wouldn’t have just walked out and said “bye-bye guys”. So the logic of distancing myself from the specific interests of what I thought to be great artists made perfect sense as I walked off into the night, into political life or more social concerns.’

So you went to France, leaving your books on rugs behind, in the care of the Asia House Gallery. And in the mid 1980s you had them shipped over to Europe.

‘That’s right. I decided to commit myself to textiles in the mid 1980s, and I did so in two parts; one was the building of a bibliography and, along side it, a library, which attempted to bring together the social, economic and technological history of textiles along with its aesthetic aspects. The other part was the collecting of textiles. But the textiles themselves have always been –even now– subsidiary to the textile library. I love books, I love to collect books, read them, catalogue them, pile them on the floor. I like everything about books, and that’s the primary concern. The textiles came a little later. Where I can say with all due modesty that I know quite a bit about the textile literature, I cannot say that is the case with textiles themselves. The collection that I’ve evolved and continue to evolve is a very personal selection, in a way. It’s not about comprehensiveness.’

Could you define a broad line of interest in the collection?

‘There is no underlying interest. Collecting textiles is for me, as it would be for anyone, also a practical matter; textiles can get very expensive very quickly and they can be difficult to find. As I said I was more interested in the building of the library. So my interest in collecting textiles and the time I could allocate to finding them was relatively sparse; the flea markets, some auctions, dealers in Paris or London, or wherever I was.’

What do you look for in the textiles you buy?

‘What interests me is that the production of textiles is divided: the domestic production is usually a feminine art, and the professional side is usually masculine. Like today if you think about cooking: the majority of professional chefs are men, but the daily-life cooking in the home is usually done by women. The embroidery and weaving of cloth for the home is a domestic affaire, often boring, tremendously repetitive with lots of work involved; ants’ work. And it’s very debilitating; always very labor-intensive. Furthermore, historically, textiles also has been a very important industry. An industry that in France during the eighteenth century was a source of riches, probably as important as the automobile industry in the 1930s in the USA. Or the computer industry today. In nineteenth-century England, because of the industrialization of the woven processes, one out of every four people were more or less involved in the textiles trade. This social-economic aspect, coupled with the idea that remarkably beautiful things were being produced, is something that grabs me.’

Could you also have collected cars, so to speak, instead of textiles?

‘Well, no. Cars can be beautiful but they have a different industrial production process. I think it’s very specifically textiles that drew my attention. Another aspect is that although textiles have a fragile aspect, they travel well; they are also a fantastic means of communication for sending images around the world. Because they did travel, whether as gifts or as commerce or as trade on the silk route, they did have a very important influence on the exchange or movement of imagery, ideas, colours and so forth.’

What does the bulk of the collection consist of?

‘There are probably three distinct parts. Most of what I was interested in are silks and velvet from Italy, from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and also French eighteenth-century pieces. Another section concerns production in the so-called periphery, in the so-called “underdeveloped”, “third world” countries, work from the Pacific, Africa and from Native Americans in the form of ceremonial objects and weaving. There are quite a lot of tapas (also known as barkcloth), which is material that comes from mostly mulberry trees and is painted or stencilled. And then there are the early textiles, often referred to as “archeological textiles”, such as Coptic, Peruvian pre-Columbian, Chinese, and Islamic. Another important category of the collection is the headdresses – the ceremonial hats and caps. So those are the main sections, I would say. There are also embroideries, costumes, in addition to woven textiles.’

It could be considered quite a jump from being one of, if not the most important, propagators of Conceptual Art to the owner of a major textile collection. Is it a jump in your head?

‘No, it’s not a jump in my head. Nor would I consider it a “major textile collection”. The bigger jump is probably from Conceptual Art to the Artist’s Contract, for example. I don’t feel like there’s a big jump here. This is my life. It seems perfectly logical to me – and don’t forget, this didn’t happen in twenty minutes, these are all projects that have developed over fifteen to twenty years, including the political publishing, the media research, etcetera.’

Do you consider how all these projects are perceived?

‘I can only say for myself that I don’t really care how well they’re perceived. I just try to do the best I can; trying to do a project as well as possible, whatever that means. This textile exhibition at Raven Row is something I had never thought about, and in a way, I couldn’t care less what people think about it, just as I couldn’t care less what people thought of Lawrence Weiner’s Statements or the January 5-31, 1969 show. I just felt, and feel, that if it has certain validity and asks some interesting questions, whether 50 people come to the exhibition or 5000 over the course of a month, it doesn’t change very much.’

Are you curious to see the textile show?

‘I am very eager to see what the textile show looks like myself, to bring them out from under closets, beds and warehouses where they have been wrapped in acid-free paper for 20 to 30 years. I haven’t seen some of these things in years. Another thing about the textiles – through them, I have really become a collector. I’ve never been a collector before. I never had an art collection, as it were. With the textiles, I feel like I’m really collecting things, like some kind of medieval merchant. And that’s a funny experience. And a little disturbing.’

You put the question to the artists participating in one of your shows in 1968: ‘What are the revolutionary aspects of the philosophy behind this work?’ Does a work need to be revolutionary in order to be good? Or do projects?

‘I wouldn’t exaggerate. I try to have a greater critical awareness than most people in our milieu. More self-critical, I’d say. But I don’t think I’m a revolutionary when you compare me – when I compare myself – to other people who really commit themselves to a certain kind of life, a certain kind of militancy. I suppose you could say that there are some artists, critics and gallerists who are more trouble-making than others. But the art world environment we live in is so privileged that the idea of revolutionary is hard to understand. Although some of them talk a good game. As someone said, “they talk the talk but they don’t walk the walk”.’

Maxine Kopsa is associate editor of Metropolis MMaxine Kopsa is associate editor of Metropolis M

Maxine Kopsa