‘Rabih! Rabih!’ Rabih Mroué in BAK

Lebanese playwright, actor and theatre director Rabih Mroué came of age during 15 years of protracted civil strife (1975-1990). His generation of artists became active in the 1990s, and has focused its practice on countering the political and historical amnesia of post-war Lebanon by excavating individual and collective memory and narratives, and querying the intricate relations between identity, mediation, representation, truth value, fact and fiction. Among their ranks are Akram Zaatari, Joanna Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige, Walid Saadek, Lamia Joreige, Lina Saneh, Jalal Toufic, Ghassan Salhab, and Walid Raad. Mroué, as his peers, has questioned the role of the artist in such a charged context: witness, narrator, chronicler, participant and agent.

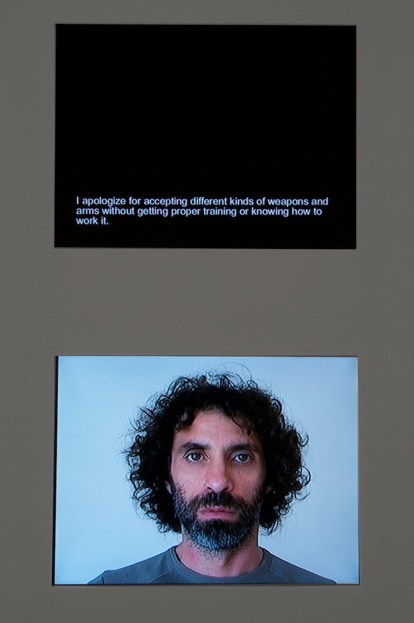

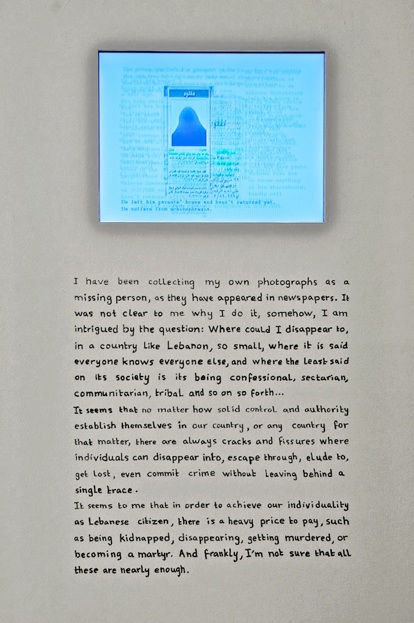

I, the Undersigned, Mroué’s first solo exhibition as a visual artist, brings together four existing and two newly commissioned works, installed over BAK’s two floors. It addresses, as many of his plays and performances do, the issue of responsibility within larger artistic and historical-political frameworks. The title is taken from his 2007 two-channel video installation I, the Undersigned, wherein he publicly apologises for his role during the Lebanese civil war. His intentions are handwritten on the wall, as if issuing a contract to the viewer, and thus immediately implicating the latter. While a monotonous voice-over recites the artist’s apologies in Arabic, the lower of the two screens shows a silent Rabih Mroué coming in and out of focus, while the upper screen features the English translation of his regret. The endless loop of apologies range from dealing specifically with his personal involvement in affairs of war, his dislike of the medium he works in, to the very nature of the apology itself, which eventually when repeated ad infinitum turns into meaningless blabber: ‘words, words, words, words’.

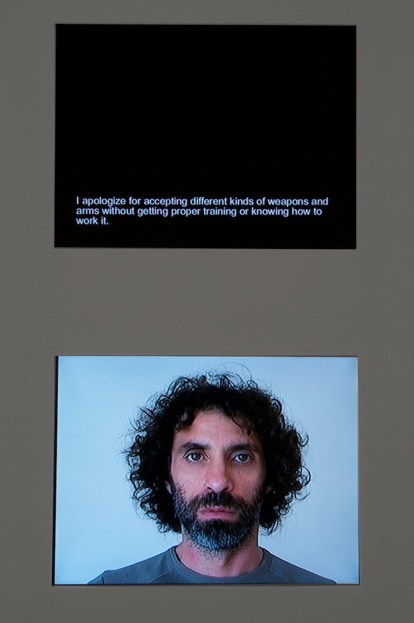

The repetitious search for a visual and textual semantics post-catastrophe is what underlines the works shown on the upper floor of the exhibition. The one-channel video Noiseless (2008) exemplifies how Mroué seamlessly oscillates between personal ruminations on national identity and the problem of Lebanon’s unaccounted for disappeared. We are shown a newspaper cutting recounting the circumstances of Mroué’ going missing, accompanied by the artist’s photograph. As Mroué’s disappearance morphs into the newspaper clippings of other missing persons his image starts to fade, until blank. Again the individual and the collective blur, as the visual traces of those who are forgotten are literally erased from the body politic’s memory. Painful reminders of the past, which are reduced to smudges and then to nothingness.

Je veux voir (2010) is a new mixed media installation based on the similarly named feature film by artist/filmmaker duo Joanna Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige (2008). Featuring French film diva Catherine Deneuve and Rabih Mroué, both as themselves, the original film is a road movie to battered South Lebanon in the aftermath of Israel’s 2006 July war. It is a cinematic exploration on how the fictional space of cinema bleeds into the real, and whether images of war can really make us ‘see’ (i.e. comprehend) anything. In this installation Mroué references and revisits this concept, but emphasises the sense of loss and the impossibility of decoding whatever is visible or found. A short edited film sequence shows Deneuve repeatedly calling out ‘Rabih! Rabih!’ in search of Mroué. In the background a wooden panel with photos taken from the debris in Bint Jbeil; Mroué’s family village in the South. The imagery seems unreal, as if part of the décor of a film set. Behind the panel, another video with close-ups of codes inscribed on the walls of destroyed buildings with Mroué’s voice reading the codes. Who put them there, to what end, for whom, what do they mean? These questions remain unanswered, the codes opaque.

If the upper floor of the exhibition deals with issues of representation in a performative and outspoken fashion, then the lower floor is much more concerned with the distribution and organisation of knowledge vis-à-vis representation. This happens in the 17’ video On Three Posters. Reflections on a video performance by Rabih Mroué (2004), installed in a formal classroom set-up, complete with desk and table in the front. Originally a performance with Elias Khoury in 2000 taking as its source the various uncut rushes found on a suicide bombers testimonial tape, the 2004 video is an analytical exploration of the conceptual and context-sensitive roles of reality, fiction, media, and politics when executed within an artistic setting. The 2004 video mimics the style of a video testimonial, wherein it is the artist Rabih Mroué who eventually martyrs his own performance. In this sense the work functions both as eulogy and as meta-text.

A eulogy of a different kind is to be found in the show’s visually most striking piece, the newly commissioned Grandfather, Father, and Son (2010), which traces the male lineage of Mroué’s family in relation to political events and the production of knowledge. As characters in a play Mroué, his father and grandfather are inscribed into a political and historical timeline on the wall which links the output of their intellectual efforts to watershed moments in Lebanese history: 1982, the year Israel invaded Lebanon; 1987, the assassination of his communist grandfather, and the assassination of then Prime Minister Rashid Karami; 1989, a particularly violent episode of the civil war which would inaugurate its end.

The installation is as much a family genealogy, as it is an index of print media that has met an untimely death: respectively the father’s unpublished mathematical treatise beautifully encased in a glass as if mummified, the grandfather’s obsolete library system with its cards shuffled and devoid of alphabetical logic, and the son’s (Rabih Mroué) first and last short story originally published in the daily of the Lebanese communist party, but recited by the artist on video in his grandfather’s library. These textual documents have been fixed within specific space-time coordinates; they have become relics of the past and annotations to a complex family history that is inextricably bound to Lebanon’s turbulent history. What is on display here only evokes the semblance of telling the full story, and only provides us with clues to piece together possibilities.

In that sense the whole exhibition can be read as a tentative script, an open performative proposal that allots the artist much of the centre stage as a key protagonist. However, every performer requires an audience, and we as viewers all become undersigned by the operations of the exhibition. Master playwright that Mroué is, it is exactly this generosity that defines the beauty and genius of his first solo exhibition.

– Nat Muller is and independent curator and critic

Rabih Mroué, I, The Undersigned, is on show untill 1st August in BAK, Basis voor Actuele Kunst. Read Mroué’s column From Rabih To Rabih By Rabih in

Film trailer of Je Veux Voir (2008)

Nat Muller