Contemporary art in Kazakhstan Foreign affairs

National pride versus divergent or subversive ideas. Luuk Heezen explores the local art scene in Almaty, Kazakhstan.

Roughly eight and a half thousand kilometres southwards from Amsterdam, in Central Asia, adjacent to Russia, China, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan, lies the republic of Kazakhstan. After the downfall of the Soviet Union in 1991 Kazakhstan became an independent country. With over 2.7 million square kilometres, it is the world’s ninth largest country. Nevertheless it has only 15.4 million inhabitants, of which a small majority is Kazakh – a population that descended from Turkish nomadic people. The other part of the inhabitants comes from one of the many countries that together used to form the Soviet Union. Therefore both Kazakh and Russian are official languages.

Since 1991 Kazakhstan is rapidly changing: the parliament and the president are elected by the people, the government appears to be working on further democratization and the high profits made on the trade of raw materials provide the money needed for luxurious buildings that make the country seem wealthy and modern. Also on a cultural level there is a lot to be constructed. Especially on the side of the ‘authentic’ Kazakh, there is a strong urge to express the national history and identity. Even art serves this purpose.

In the shopping district in Almaty, the former capital of Kazakhstan, salesmen sell paintings that depict national elements of pride: Kazakh in traditional costumes, jurta’s (tents that are coated with animal skin) and many mountain and river landscapes. It’s as if they are magnified souvenirs of the mountains that surround the city – be it not for tourists, for there isn’t many tourism there: the paintings seem to function as a mere reminder and confirmation of the history of the country, comparable to the way painted VOC ships are supposed to represent a part of the Dutch roots.

And even the official galleries sell these landscapes by the dozen, supplemented by the occasional imitation of a portrait in Viennese Jugendstil, or a romantic cityscape. One gallery showed, in collaboration with the Ministry of Cultural Affairs, in a socialist realistic way what Kazakhstan had looked like at the time of key events in recent history, including a painting of a home-grown Elvis-like pop star. There is no sign whatsoever that the artist based his work upon personal motives or interests, nationalistic elements prevail.

Extensive research showed that there is only one gallery in the city of Almaty that is engaged in contemporary art. Gallery Tengri Umai is located on the ground floor of an old flat from the Soviet era, right behind a large shopping street. Its name is derived from two major gods that feature in ancient Kazakh legends. Tengri meaning sky and Umai meaning earth, the combination of the two represents both the celestial and the earthly origin of true art.

When we discuss the state of contemporary art in Almaty, director Vladimir Filatov tells me he is not too fond of the galleries of his ‘colleagues’: “They are like department stores, selling the simple and so called national art that the officials approve of.” In his own gallery Filatov likes to show experimental art, both from Kazakhstan as from other countries, and in different media. He prefers the work of young artists, because of their ability to produce new ideas.

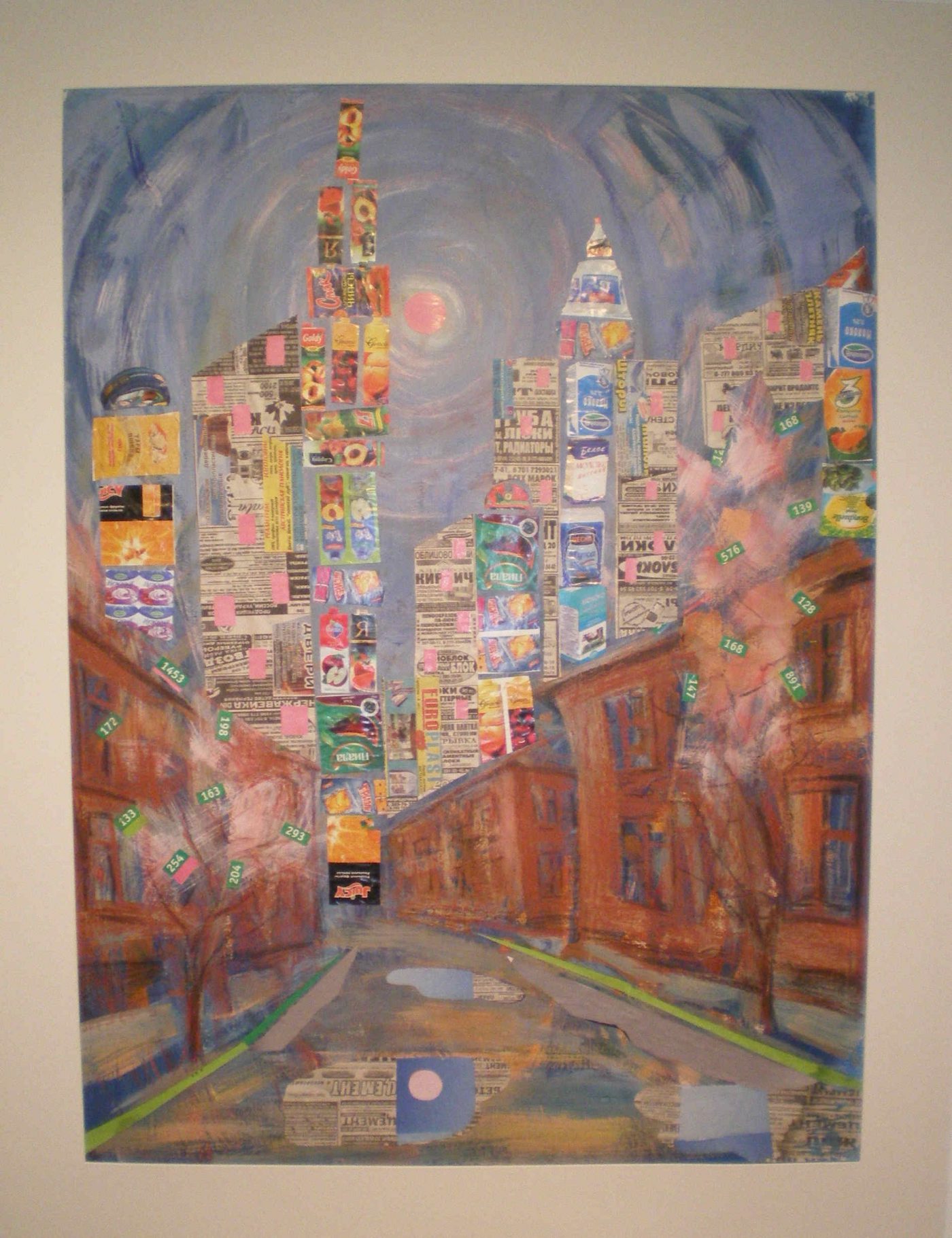

At the time of my visit, the work of local artist Dinara Akbuzau is on display. With her collages she wants to give an insight in how commercials replace our daily reality with imaginary hyper realistic perspectives. In my opinion, she doesn’t succeed in doing this. To me the collages appear to be more abstract than hyper realistic, and more childishly naive than revealing. Nevertheless, in the abundance of nationalistic nature scenes, it is refreshing to see work that is produced out of personal interest, rather than to meet the demands of a monotonous art market.

It turns out I’m not the only one with this attitude. Filatov does sell some of the work that he shows, mostly to businessmen of private companies. But as soon as the companies grow, the state system interferes. And the government policy prefers national pride over divergent or possible subversive ideas.

To maintain total autonomy, Filatov therefore choses to abstain from any governmental ‘support’. This doesn’t make him the most popular man with the authorities, but he is persistent. In 2000 and 2002 he organised an impressive art festival with hundreds of international artists and guests, and once every two months a young artist gets the opportunity to show his work. But Filatov knows he is swimming upstream. He doesn’t expect to find a vivid art scene in Almaty anytime soon: “Our society would need to be more open to new ideas to achieve that."

Gallery Tengri Umai www.tu.kz

Luuk Heezen