The Last Brucennial

Since 2008, anonymous New York artist collective the Bruce High Quality Foundation has staged a scrappy, large-scale bi-annual exhibition called the Brucennial. Both a send-up of and an alternative to the Whitney Biennial, with which it has always run concurrently, this year’s iteration promises to be its last.

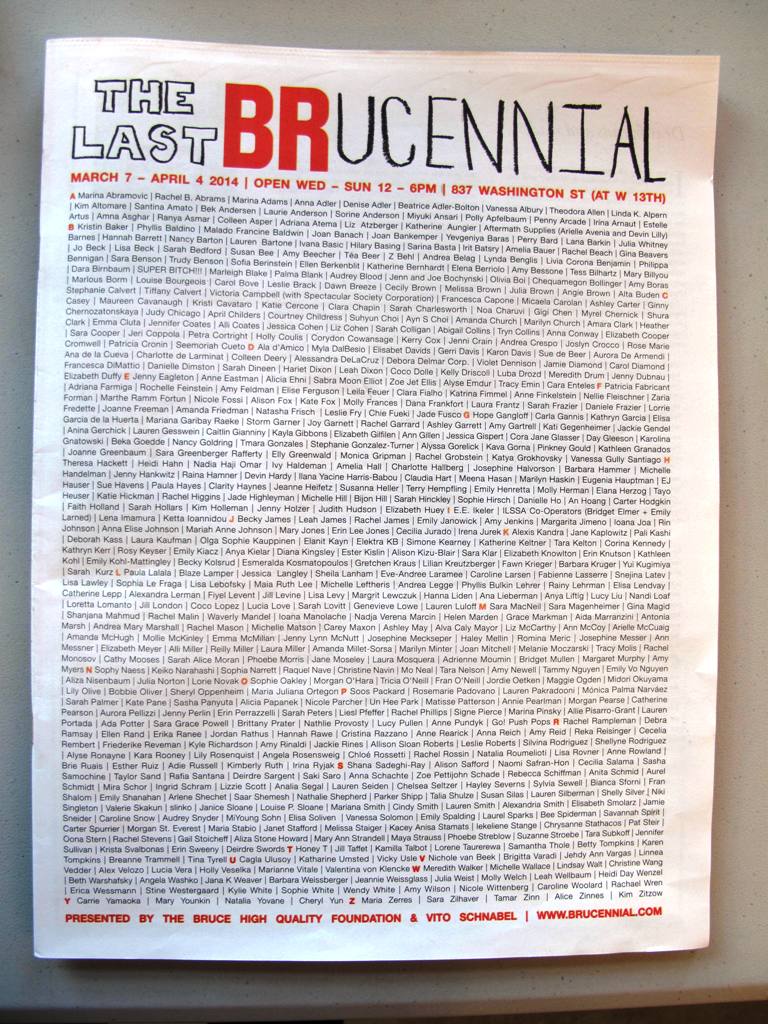

As with previous years, what has been officially dubbed The Last Brucennial operates according to an open-call policy, with one exception this year: the Brucennial will be exhibiting female artists only. The Last Brucennial features the work of over 600 female artists, a mix of virtual unknowns to some very seminal names indeed, such as Barbara Kruger and Louise Bourgeois, whose inclusion is presumably facilitated by the involvement of Vito Schnabel, billed here alongside the Bruce High Quality Foundation as the exhibition’s presenter.

While art fatigue is probably an unavoidable consequence of a show this size, the necessary suspension of critical judgment that comes with this kind of sensory overload feel oddly productive.

Speaking over email with the organization’s ‘spokesman,’ Bruce, the BHQF is quick to acknowledge the close involvement of Schnabel—“Vito and his team have been involved in all aspects of organizing the exhibition.” It’s a relationship that appears to have worked out well for the collective, who have been involved with Schnabel since 2010’s Brucennial and who have since courted a perhaps surprising degree of success for their brand of art-school pranksterism meets institutional critique, including, most recently, a retrospective show at the Brooklyn Museum.

While the Brucennial’s name intentionally evokes the Whitney Biennial, they don’t seem to see much of a connection between the two events. “We don’t think there’s much of a relationship; they do their show and we do ours.” This kind of brusque response is typical of group’s willfully obtuse PR strategy, but it is followed up with the suggestion that perhaps their show has gotten attention “in proportion to the fatigue a lot of people feel with the Whitney’s show.” “But beyond that,” they note, “We never conceived of it as a ‘take-down’ of the Whitney. It certainly hasn’t accomplished anything of the sort.”

With an overwhelming amount of work chaotically jammed into a large ground-floor space in the Meatpacking district—which, incidentally, sits immediately opposite the future site of the Whitney Museum of American Art once it moves downtown in 2015—it’s an understatement to say the show resists easy summation.

Wandering around the space’s winding series of rooms can feel akin to listlessly scrolling through a Tumblr feed, with artists’ names scribbled next to sometimes awkwardly juxtaposed works underlining the exhibition’s deliberately amateurish approach. There’s something decidedly surreal about stumbling across a work by Jenny Holtzer flanked by the work of unknown artists. While art fatigue is probably an unavoidable consequence of a show this size, the necessary suspension of critical judgment that comes with this kind of sensory overload feel oddly productive, forcing the visitor to resist the urge to contextualize the work and identify trends in lieu of any press release or artist bios.

Despite this, certain works have a way of sticking with you more than others. Young Brooklyn painter Sheryl Oppenheim contributed a piece that overlays textiles with a kind of mountainous, abstract figuration. Consisting of a small square of fabric, upon which tense, energetic lines of color are painted, and which is itself placed slightly askew over a ubiquitous vintage textile pattern, the enigmatic painting is suggestive of the tension between the obsolescence of mass produced aesthetic objects and their potential repurposing.

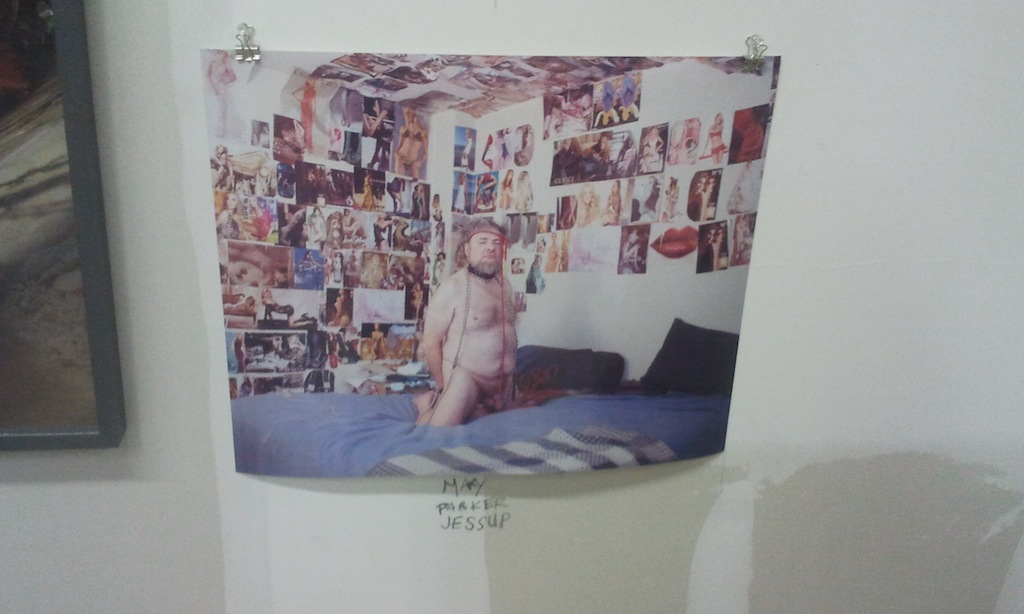

Mary Parker Jessup’s photograph of a naked middle-aged man chained up on a bed in a room whose walls are plastered with images of women in varying states of undress uses fetish culture as a way of continuing her exploration into the points at which sexuality, our public and our private personas overlap. And there was some especially strong work on the display in the sculpture/mixed-media vain, for instance the disturbingly cybernetic installation by Lena Imamura, which combined a flat-screen tv and long, flowing hair embedded in a wall-mounted, translucent pink cube.

There is something incredibly appealing about the flattening effect of its anti-curatorial approach.

While there were some very conspicuous examples of recognizable pieces by well-known artists, the more pleasant surprise turned out to be new work from artists I was already familiar with. On a cluttered wall bisecting the space was a new piece by Josephine Meckseper, featuring three knives seemingly flung into its brash red canvas. Another highlight was a large sheet painting by Amy Beecher, whose murky color gradients and embedded textures approach an effortless sublimnity.

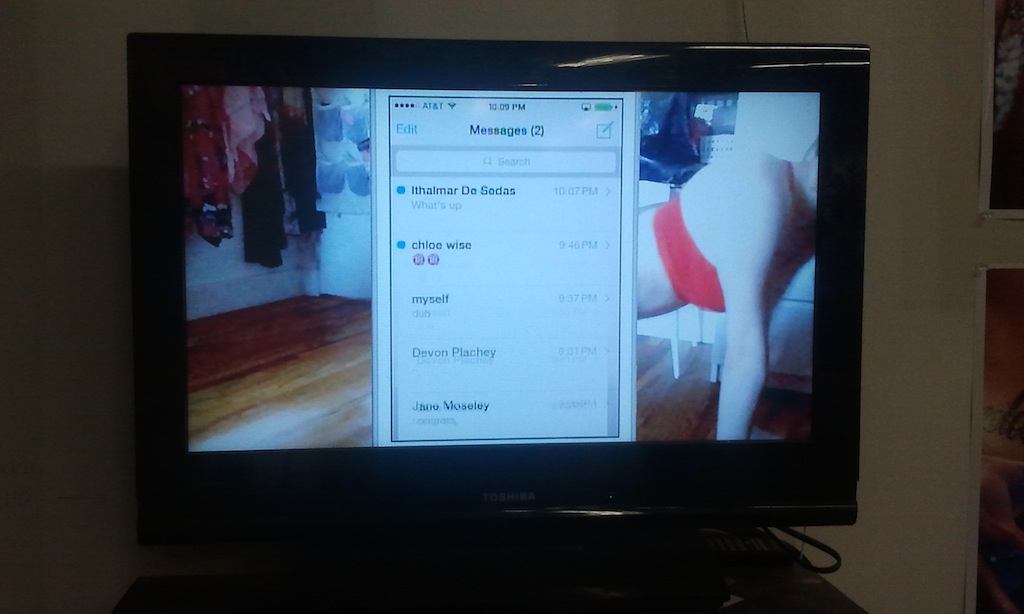

Video also received an especially strong showing from mostly younger artists. Alexandra Mazella (better known online as Rosey Diamond or artwerk6666) contributed a piece that features clips of herself performing on video chat, while screenshots of text message exchanges periodically flashed up onto the screen.

One of the Brucennial’s most compelling pieces was Signe Pierce’s and Alli Coates’ American Reflexxx, an unscripted short film that follows Pierce as she walks down the street in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina dressed like a stripper and wearing a silver, convex mirror on her face. Depicting Pierce repeatedly being assaulted and having things thrown at her, it makes for disturbing viewing, particularly when taken in conjunction with its schizophrenic, glitchy editing style.

The Last Brucennial’s anarchic atmosphere can occasionally feel exhausting, but there is something incredibly appealing about the flattening effect of its anti-curatorial approach. In this sense, it is both symptomatic of and reflexive about an art system that is turning out more artists than it reasonably knows what to do with, offering what is simultaneously a dumping ground for young artists, an ‘alternative’ exhibition platform to both the gallery and biennale systems, as well a mode of access to this very infrastructure.

The Bruce High Quality Foundation’s negotiation between these multiple positions is not without its problems, but it’s difficult to fault the Brucennial’s pretension-free approach. It’s sad to see the Brucennial disappear, but with the organization wanting to direct more resources to their free art school The Bruce High Quality Foundation University, the decision for this year to be its last can hardly be considered shying away from their principles.

The Last Brucennial

837 Washington Street, NYC

7 March – 4 April

Thanks to Rosa te Velde for the extra images

Tim Gentles