installation shot of Pungulume, Sammy Baloji, (2016) copyright Lavinia Wouters

An intimate biennial: the opening weekend of Contour

For the 9th edition of the Contour Biennale, Coltan as Cotton, curator Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez established a radically different time frame to the biennial and aligned its duration, three weekends in 2019, to the lunar cycle. The first weekend is promising.

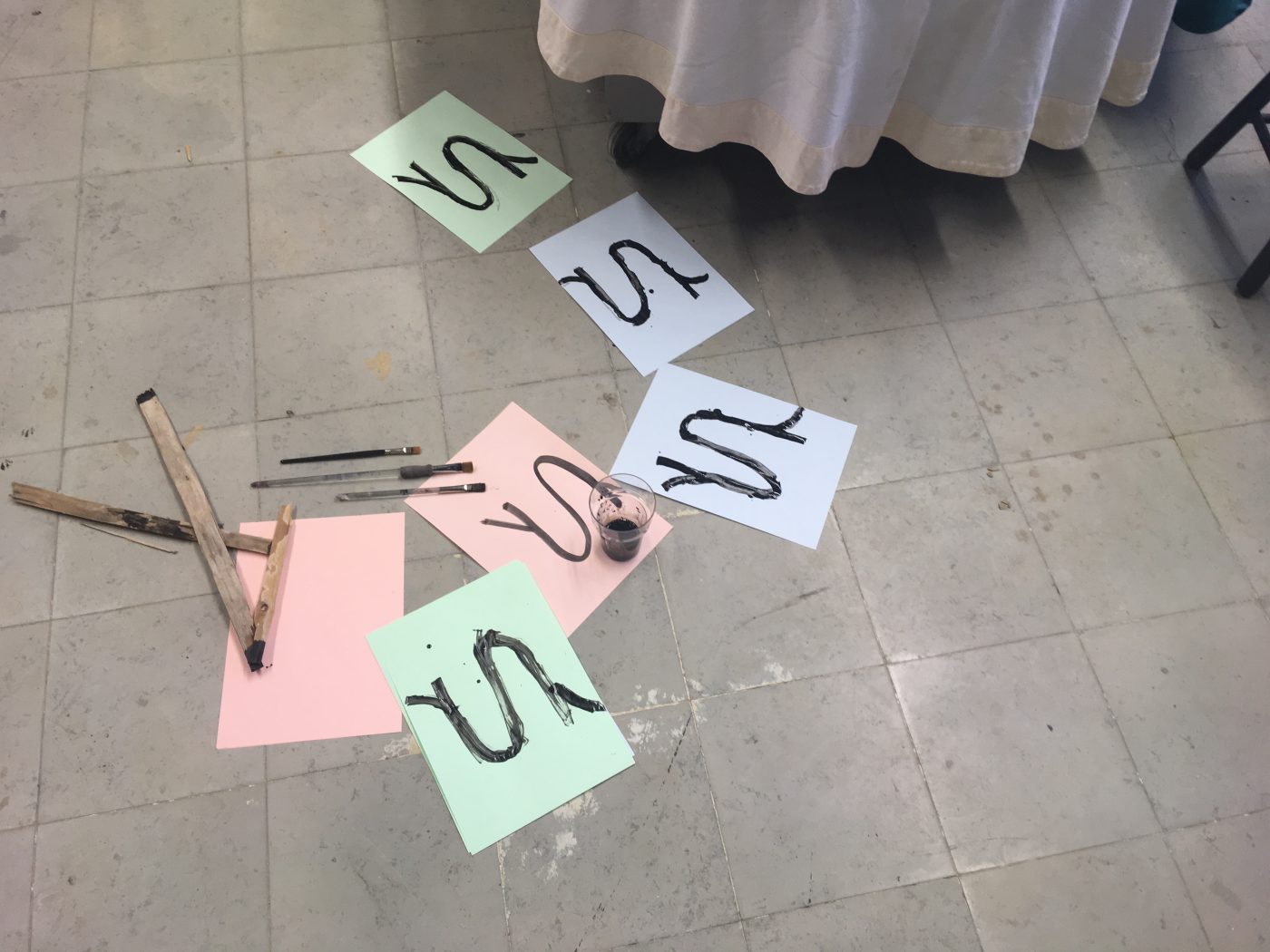

On an early Saturday morning, I found myself in the snug setting of a sculpture studio in the Mechelen Academy. This is where artist Cadine Navarro staged a workshop exploring the signage system of compost, as part of her ongoing project Black Gold. Energy, balance, soil, fertility and ground were some of the notions that came up during this brainstorming session, before we grabbed our pencils to start drawing signs that could symbolize such concepts. Navarro will share the final result with the artist collective Coyote, currently working on a visual glossary of terms related to our contemporary ecological moment. It was a pretty original kick-off for the day, setting an intimate tone that was maintained throughout the rest of the talks, screenings and workshops.

For the 9th edition of the Contour Biennale, Coltan as Cotton, Paris based Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, orchestrated a particular experience. Rather than opting for a conventional exhibition format – e.g. a show running for 2 months, loaded with art professionals during the opening and then, commonly, visited by a mere 3 people a day – the curator established a radically different time frame. Aligning with the lunar cycle, the Contour Biennial will have, in total, three moments of public visibility throughout 2019: this first iteration, in January, corresponds to the waxing crescent moon, a second one in May during the full-moon and, lastly, a concluding session in October. This edition also marks the beginning of an official collaboration between the Contour Biennial and the Mechelen based Nona arts centre.

Black Gold (outdoor installation), Cadine Navarro” copyright Lavinia Wouters

Some drawings from the workshop Black Gold by Cadine Navarro, photo by Kyveli Mavrokordopoulou

The weekend of 11-13 January was filled with conversations around (de)colonization related to the Belgian context. After the morning workshop, we were greeted in the main venue of Nona, to attend a “Heart to Heart conversation” between two important artistic figures of the Belgian context: Monique Mbeka Phoba and Laura Nsengiyumva, representing two consecutive generations of artists working in the field of art and decolonization. Their exchange, which took place on a cosy couch surrounded by houseplants, felt like a mother to daughter conversation, as the discussion revolved around the family histories of the two women. Along those lines, both artists spoke about the importance of the transmission of language and culture, a discussion that, inevitably, touches on the multiple obstacles that forestall transmission processes. Reflecting on her own background, Nsengiyumva fondly stated that “decolonization can only be an intimate process,” a remark that aptly captured the surrounding atmosphere throughout the day.

The succeeding event by the film collective Greyzone Zebra also felt intimate, albeit on a different, more unsettling level: some members of the collective explained to the public that they collect, through open calls, family films shot during the colonial period. Usually, such unedited material is left sitting in dusty basements, unseen by younger family members. What is compelling about these reels is that they offer a very different narrative from that of official propaganda films, which the collective defined as “traces of untold stories.” After watching a short home movie filled with several disturbing images (some of them shot around Lake Kivu), each member of the audience was invited to write down their impressions and to then read them out loud in a circle setting. Most felt reticent to share private thoughts. This generated several awkward moments of silence, spent looking around and avoiding gazes – a situation that attests to our own “awkwardness” when addressing such images and openly discussing the complicity entailed in the production and experience of these images today. Yet working through our own uneasiness is an inherent and irreducible part of the process of apprehending the often shrouded traces of the colonial project. Thus, mounting similar intimate (and uncomfortable) frames could initiate more confrontational discussions within what Walter Mignolo has called decoloniality, which refers to a process of detachment from dominant structure of knowledge in order to engage in an epistemic reconstitution (of mentalities, language, and ways of being in the world).

Maarten Vanden Eynde’s paintings, commissioned by Contour 9, photo by Lavinia Wouters

Finally, the accompanying exhibition (the only non-discursive format in Coltan as Cotton) took place in the new venue of the Nona arts centre. The two artist run organisations Picha from Lubumbashi and Enough Room for Space from Brussels, initiated On-Trade-Off together, an experimental research project that deals with lithium, a mineral used for batteries, currently described as the “black gold of the future. The show paid special attention to ecological matters and this is the moment where the title, Coltan as Cotton, becomes most explicit. Coltan is an essential component for several cutting-edge electronic devices, but the methods employed to extract it are not modern at all, in fact, it is mined by hand. The most prominent contemporary example of conflict minerals, a term denoting the violence and armed conflict which accompanies the extraction of valuable minerals, is found in the eastern provinces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. As Petrešin-Bachelez notes: “a large percentage of coltan today derives from the DRC, a country that, for the past 20 years, has been home to one of the deadliest conflicts since the Second World War.” The above two artists offer an expedient reflection on such conflict minerals and the paralleled, intertwined histories of colonialism and the resource extraction economy. Sammy Baloji presented his film Pungulume (2016), which zooms in on the history of the copper mining industry in the province of Katanga, DRC (the ground zero for conflict minerals). The video depicts a landscape that has been irrevocably destroyed by the continuity of (neo)colonial exploitation, a theme complemented by the paintings of Maarten Vanden Eynde and Musasa of extracted materials such as uranium and lithium. Together, the two works disclose the deep patterns of exploitation still pervading the DRC.

The gradual unfolding of Coltan as Cotton, both throughout 2019 and during this past weekend, along with the intimate atmosphere of the events, is in many ways a realisation of Petrešin-Bachelez’s plea for “slow institutions”. Riffing on Isabelle Stengers’ “slow science,” an invitation to slow down research in the social and hard sciences, the curator explains what this entails: “The traditional exhibition format can no longer hold: Coltan as Cotton aims to reconsider not only conventional patterns of biennials, but also the working conditions within the exhibition itself. Transport of artworks from other parts of the world and their packaging usually constitute a tremendous ecological expense, which is poorly addressed in exhibition contexts.”

Exhibitions pay lip service to their environmental impact, leaving a gap between theory and praxis. Petrešin-Bachelez continues: “Hence, the fact that we have few moments of public visibility allows for longer, uninterrupted working periods for the artists, but also for fewer transports. The participants make on-going productions. A big number of our artists are based in Belgium and will participate in the different phases of Contour, showing sometimes work in progress throughout these phases.”

Such arguments echo like an unpretentious invitation to move the two parallel struggles of decolonial and ecological justice beyond theoretical, art-world discussions alone.

Kyveli Mavrokordopoulou

is doing a PhD at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris, on expanded notions of time in environmental art