Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Touch Sanitation Performance, 1979-80, July 24, 1979-June 26, 1980. Citywide performance with 8,500 Sanitation workers across all fifty-nine New York City Sanitation districts, May 14, 1980, Sweep 10, Manhattan 11, photo: Deborah Freedman, © Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

The museum archive as feminist construction site — “I’M NOT A NICE GIRL!” at K21 – On Hold #6

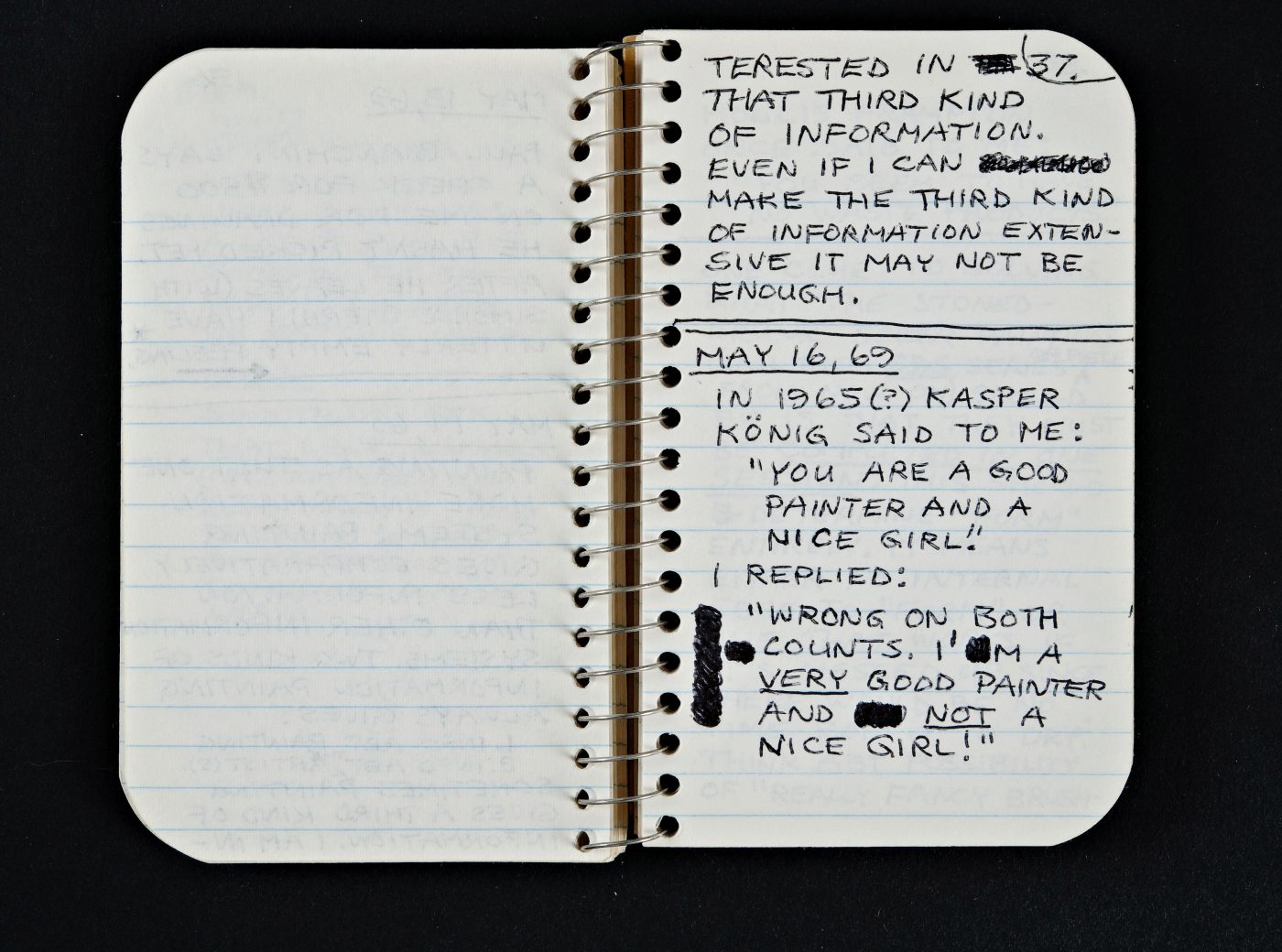

“You are a good painter and a nice girl” German curator Kasper König patronizingly assured artist Lee Lozano in 1969. Lozano answered: “Wrong on both counts. I’m a very good painter and not a nice girl!” Her quip now lends a group exhibition of all-women conceptual artists in K21 in Düsseldorf its title.

In I’M NOT A NICE GIRL! the work of Lee Lozano is brought together with pieces by Eleanor Antin, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, and Adrian Piper, all of whom played a central role in early Conceptual art. Their artworks are put into dialogue with documents drawn from the museum’s Dorothee and Konrad Fischer Archive, many of which illustrate the systemic erasure of women from the contemporary art landscape of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. In her written introduction to the exhibition, curator Isabelle Malz argues that the show reveals “the contradictory ways in which art historiography is constructed” and questions the archive’s propensity for “reinforcing existing conditions and cementing hierarchies.”

Though the exhibited documents and texts are presented to tell a specific story about how gender inequality has been fostered and perpetuated, the artworks on view speak for themselves, offering subtle—or sometimes brazen—indictments of the biases and power imbalances that governed the era in which they were produced. Malz—who conceived the exhibition design with artist Katrin Mayer—gives each of the four artists her own dedicated gallery space, with work by Antin, Ukeles, and Piper installed on the museum’s second floor and Lozano’s work displayed one level below.

[blockquote]The artworks on view offer subtle —or sometimes brazen— indictments of the biases and power imbalances that governed the era in which they were produced

Wall space is reserved for artworks while vitrines hold the archival materials, a helpful distinction as many of the included works are documentary or text-based. The archival documents are installed inside black rectangular outlines printed onto long sheets of semi-transparent paper that Mayer designed in reference to the grid systems that so prominently feature in Conceptual art. The exhibition offers visitors many opportunities to pause and reflect, whether in front of looped videos playing on boxy Hantarex monitors or at tables laden with books by Lippard, Piper, and other influential critics and theorists.

Installation view of the exhibition I’M NOT A NICE GIRLat K21, Bel Etage and Dorothee and Konrad Fischer Archives, North Rhine-Westphalia Art Collection, photo: Achim Kukulies © Kunstsammlung NRW

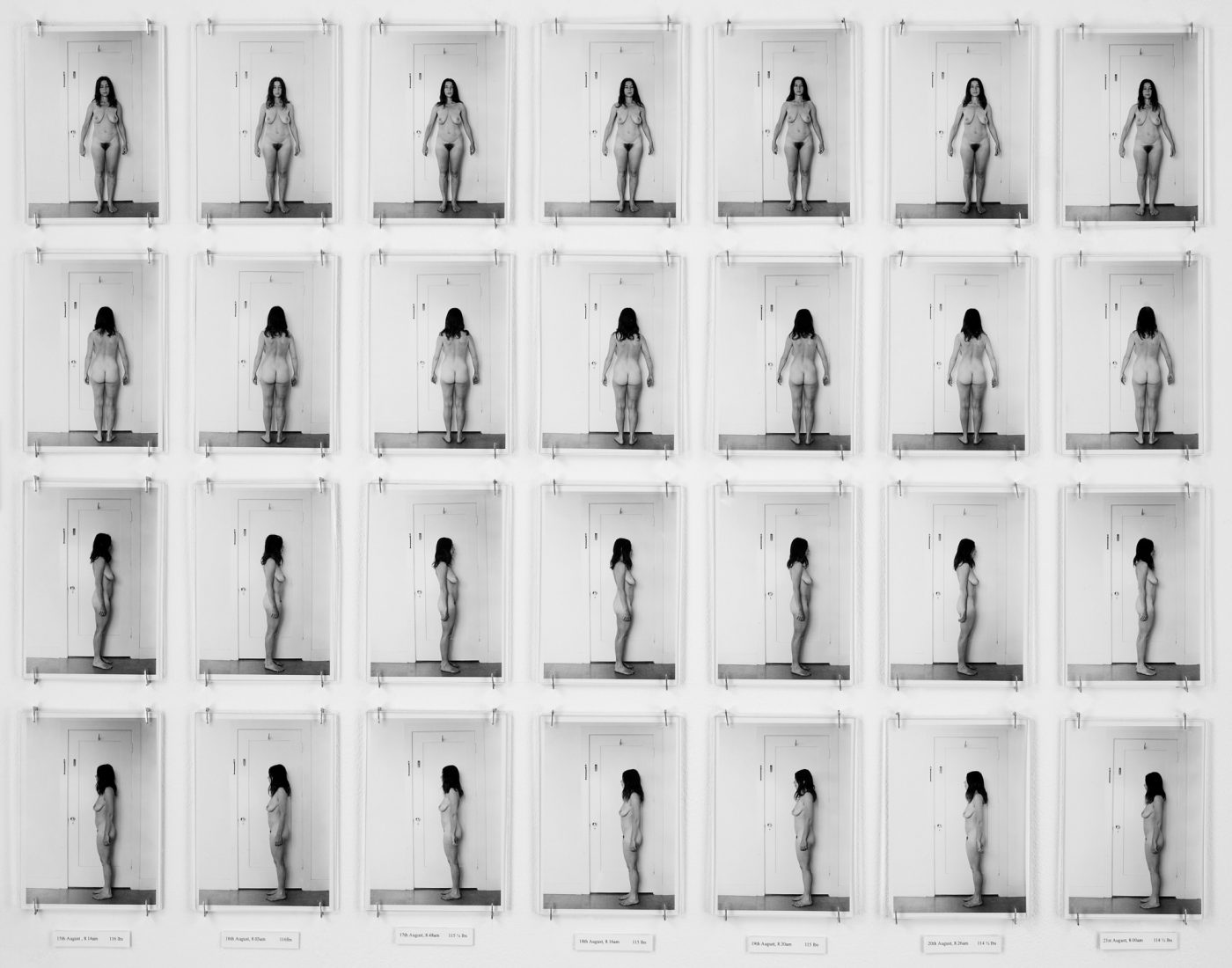

Eleanor Antin, Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, 1972 (Detail), (The Last Seven Days), 148 silver gelatin prints & text, 7 x 5 inches each, From the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, Courtesy the artist and Ronald Feldman Gallery, New York

Adrian Piper, Infinitely Divisible Floor Construction, 1968/refabricated 2002. Mixed media floor installation, tape and wooden plates. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin and Generali Foundation. Photo: the author

Both the documents and artworks demonstrate the multifarious formal and ideological overlaps between the four exhibited artists. Lozano’s work No title (1970), with its neat rows of squircle-shaped perforations that expose the canvas’s stretcher and the wall behind it, is put into conversation with Piper’s mathematics-inspired wooden floor piece Infinitely Divisible Floor Construction (1968/2002), installed upstairs. Together these two works raise questions about the physical and perceptual limits of an artwork.

The three artists exhibited upstairs prominently feature their own bodies in long-durational performance works and rely on photography to document and preserve them. In Carving: A Traditional Sculpture (1972), Antin sets out to make an academic sculpture using her naked body in place of a more traditional material such as marble or bronze. For over a month, she followed a strict diet regime and gradually shed weight until she achieved the slender figure patriarchal society deemed the female “ideal.” Ukeles similarly questions traditional cultural expectations of women in her now canonical work Touch Sanitation Performance (1979-1980), in which the artist shook the hands of each of New York City’s 8,500 sanitation workers and pantomimed their movements while they worked in order to challenge the sexist and classist devaluation of “maintenance work” as feminine and insignificant. Alongside Antin’s and Ukeles’s works, photo and video documentation of several of Piper’s performances, including her influential cross-dressing project Mythic Being (1973-75), are shown as well.

Piper reminds us: “Galleries and museums are public spaces. Public spaces are political arenas in which power is gained, recognized, underwritten, disputed, attacked, lost, and gained.”

Adrian Piper, Catalysis IV, 1970. Performance documentation. Five silver gelatin print photographs. Each 16" x 16" (40.6 cm x 40.6 cm). Detail: photograph #5 of 5. Photo credit: Rosemary Mayer. Collection of the Generali Foundation, Vienna, Permanent Loan to the Museum der Moderne Salzburg. © Adrian Piper Research Archive Foundation Berlin and Generali Foundation.

Though the exhibition’s presentation of Fischer’s correspondence with various female artists and the feminist critic and curator Lucy Lippard suggests that he took an active interest in discovering artwork by women, Malz notes that his influential Düsseldorf gallery almost exclusively exhibited men. While a majority of the show’s archival materials reveal a pervasive but likely unnoticed sexism—such as Fischer’s list of planned studio visits with New York artists, roughly 90% of whom are male—certain documents express outright prejudice, as in a letter from Fischer to König in which the former argues that “a two-woman exhibition is quite the same as a one-man show.”

Certain documents express outright prejudice, as in a letter from Fischer to König in which the former argues that “a two-woman exhibition is quite the same as a one-man show.”

In addition to works by the four American artists and archival materials connected to their respective practices, the exhibition also features documents from the Fischer Archive related to the work of Agnes Denes, Hanne Darboven, Alina Szapocznikow, and Charlotte Posenenske. It is unclear why Malz chose not to include artworks by these European women, who arguably would have provided an alternative perspective and further enriched the presentation. Still, the exhibited materials effectively convey the importance of art-historiographical inquiry and a continued reassessment of our institutions of knowledge production. Malz states that she hopes “reactivating and reevaluating” the archival documents will introduce “new questions, forms of access, and perspectives.” In this sense, hers and Mayer’s exercise in reinvigorating the archive through curatorial intervention can be understood as part of the “move to turn ‘excavation sites’ into ‘construction sites’” that art critic Hal Foster identifies in his analysis of the “archival impulse” in contemporary art.

Lee Lozano (1930–1999), Private Notes

In a 1980 essay cited in the exhibition’s accompanying publication, Piper reminds us: “Galleries and museums are public spaces. Public spaces are political arenas in which power is gained, recognized, underwritten, disputed, attacked, lost, and gained.” In I’M NOT A NICE GIRL! the museum and archive emerge as sites where this kind of ongoing negotiation and reconstruction of power and history continually transpire. By opening up the Fischer Archive and putting its materials into dialogue with works of art, the exhibition encourages visitors to reflect on the complex relationship between artworks and the bureaucracy that has always surrounded, supported, and—in many cases—limited them.

“I’M NOT A NICE GIRL!” is on view at K21, Düsseldorf through May 17, 2020 (now temporarily closed due to corona measures)

Lexington Davis