Claudia Martínez Garay, Pusaq Pacha (detail), 2021, installatiebeeld No Linear Fucking Time, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2021–2022, foto: Tom Janssen

Crip time, queer time, deep time, non-human time…: ‘No Linear Fucking Time’ at BAK, Utrecht

In the dominant framework of capitalist modernity, time passes on objectively, possessing the promise of linear progression. Circulating through BAK’s exhibition space again and again, Cara Farnan notices how her grasp of this homogenizing, ‘progressive’ and devastating time disintegrates. Slowly but surely, she starts to sense the plural, subjective and sustainable ways of time the artists attempt to make tangible.

I circulate many times, upstairs and down them. Coming back again and again for second glances and closer inspections. In the hours I spend here I am mostly alone with the work and I enjoy the unrushed pace of everything, getting lost in taking my time.

Throughout the space, rhythm is kept by the overlap of beats, footsteps and ticks which spill beyond their sources to mark time for the other works too. Tap bom tap bom tap bom hums a part of Yuri Pattinson’s World Clock (True Time Replica) on the second floor. Its delicate vibration is tactile if you stand close enough. A stretched skin with a surprising warmth, a ticking we associate with life rather than the harsh mechanics of time pieces. Its urgency is closer to that of survival than of production, schedules and deadlines. Or so I feel as I stand with it the first time.

Later, downstairs, I find myself confronted with its skeleton. On the first walk around, I had not noticed that this was all one work. The apparent softness I had felt upstairs is shattered as I encounter the complex mechanics which gave rise to that gentle tick; a chip scale atomic clock developed by the US military, descendant of the time military time pieces which helped to drive colonial expansion, and which now has roles in shipping, online commerce, high frequency trading, hydrocarbon exploration and defense. I am devastated by this deception.

As I look around now, clouded by that betrayal, I feel myself surrounded by all kinds of pretenses. Simone Fattal’s clay figures and Hemali Bhuta’s works wear masks of prehistory, laid out as if they were relics of long forgotten histories. In Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz’s (No)Time bodies stop and start, hair falls in slow motion, chains swing while the dancer is still, a figure’s reflection appears for a moment then vanishes. I cannot tell what is real stillness, and what has been digitally manipulated.

Simone Fattal, Woman Lying (2013), Fragment (2003), Apparition (2008), High Priest in Ugait (2003), Warrior (2018), Woman Sitting in a Garden (2006), War (Jenin) (2006), installatiebeeld No Linear Fucking Time, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2021–2022, foto: Tom Janssen

The devastation I felt with Pattinson’s work hit me because of the arbitrary order in which I encountered its elements and I find myself meeting many of the works in the show in a similar way. The clock in Tehching Hsieh’s Time Clock Piece speeds around. Hours fill up endlessly in the background. Time loops. My mind is wandering over the mechanics of how it was filmed, and only slowly do I notice the accumulation of time in the growing mop of hair on the artist’s head. I had started watching in the middle of the film. The context outlined at the beginning only comes later.

However, deception implies that there is some absolute version of the truth, or a precise and unchangeable time. In their play with what seems at first a deception, these works instead show how quickly our grasp of a ‘true time’ disintegrates. Perhaps the exact date in which Fattal’s figures were made has nothing at all to do with their ability to recall the past and be embedded with history. And while the spread of Hemali Bhuta’s works may appear to simply imitate true archaeology, this does not mean that the materials of the objects shown are not ancient. What appears at first to be deception, turns out to be merely a different ordering of what we had considered to be linear truth. An interruption of certain systems or dominant modes of thought which had established themselves as ‘only natural’.

Antonio Paucar, Círculo del Altiplano (The Altiplano Circle), 2009, installatiebeeld No Linear Fucking Time, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2021–2022, foto: Tom Janssen

Antonio Paucar’s Time Exchange questions value; one such notion which can appear to us as ‘natural’ or ‘self-evident’. A paper clip, nail clippers, sweeping brush, a pen, a spiderman poster, a lighter, some fingernail clippings. All of the objects pictured there seem to circulate without direction. They do not follow the usual trajectory of value; either increasing (like property or antiques) or decreasing (like cars and tech) over time, but always in only one direction. Instead, their worth is decided by the hands that hold them. Within the grid these items form their own connections. They reach for one another and group themselves together. Nail clippers and fingernails, the three chains, the round things, the shoes. Objects of faith, of fun, of survival.

Antonio Vega Macotela, Time Divisa (Tijd Betaalmiddel) 351-357, 359-361, 2010, installatiebeeld No Linear Fucking Time, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2021–2022, foto: Tom Janssen

Like the kinds of time this exhibition seeks to understand, these objects move in and out of one another. Are held by many owners and are related to by each owner differently.

Spatially, the exhibition as a whole is set up in a way that allows for similar kinds of reaching, full of the possibility for interjection, small disruptions, and endless return. The works talk to one another well. Each time I return to a piece, I carry with me my previous interactions with it, and all that I have learned from the other works I pass. The more I walk around, the more I feel a sense of order falling away.

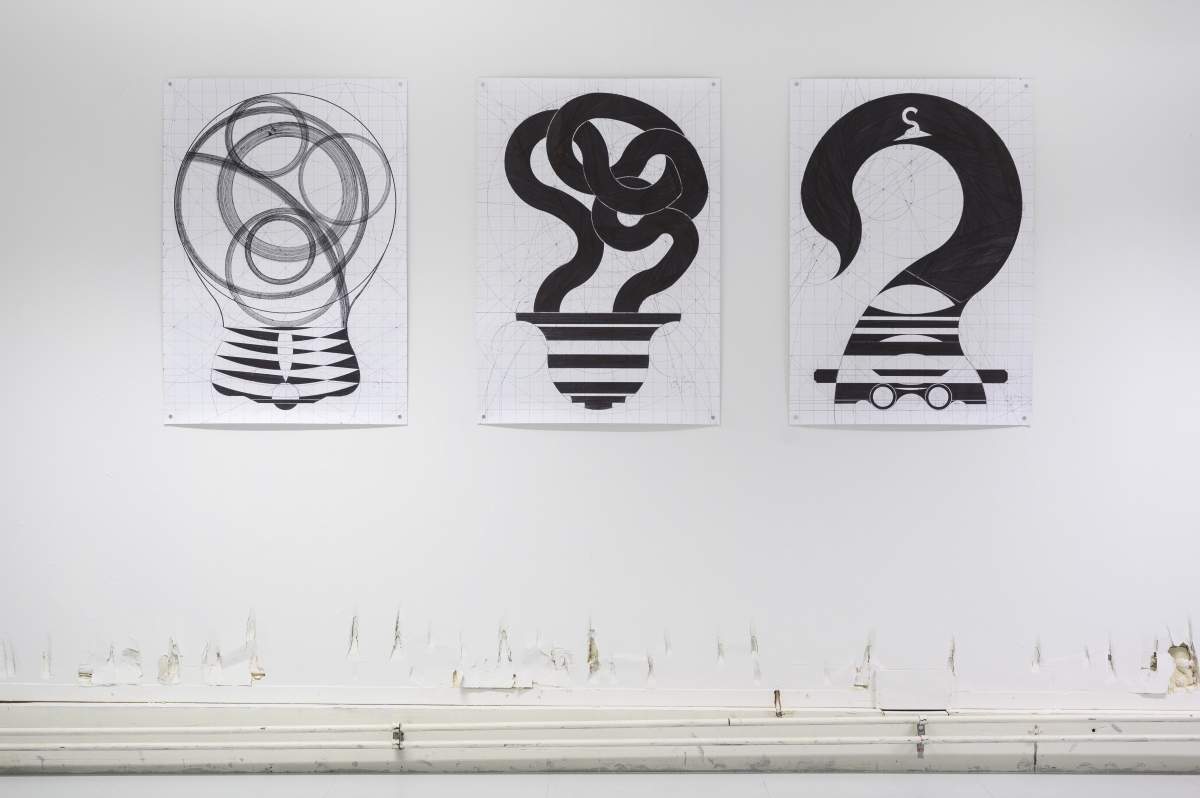

Jean Katambayi Mukendi, Covid Afrolampe 1-3, 2020, installatiebeeld No Linear Fucking Time, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2021–2022, foto: Tom Janssen

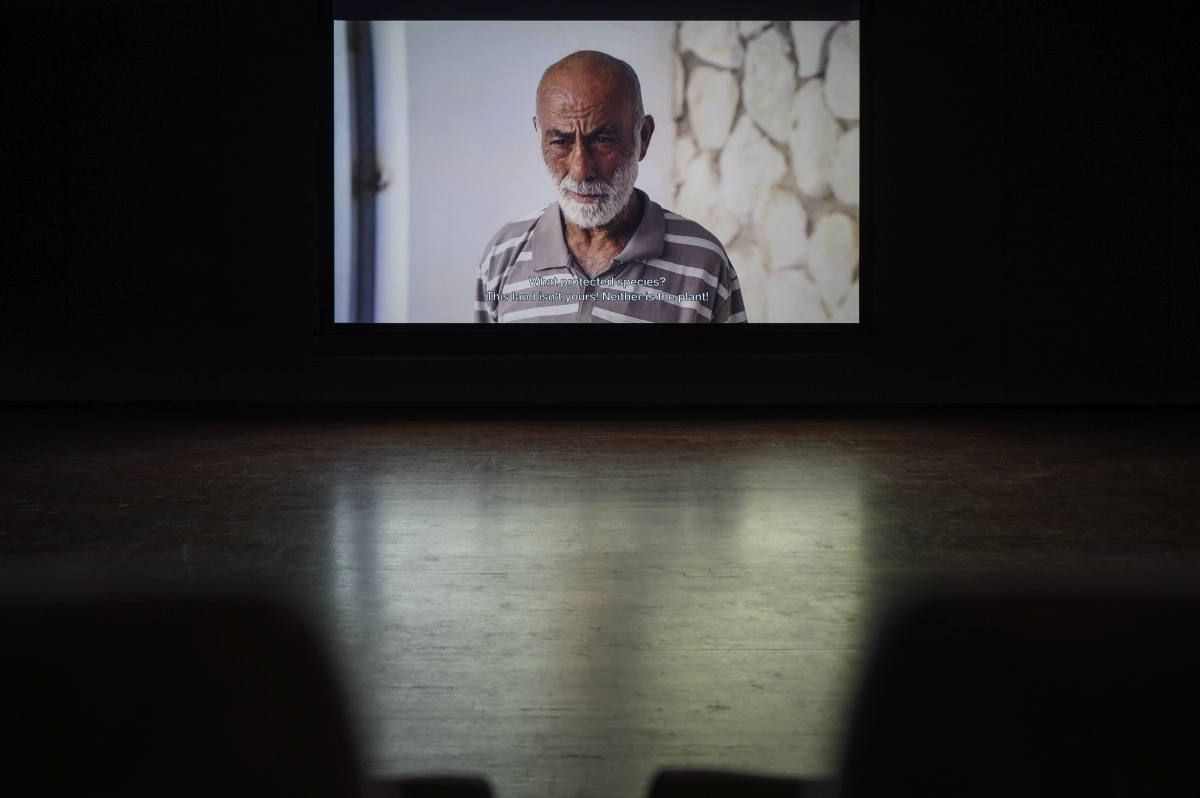

I examine one of Rita Ponce de León’s drawings Pages on a balcony; a figure is stretched, fingers and toes curled around edges, a tiny cross hatch, a miniature calendar with days blacked out marks her skin. As I do, I hear a knife scratching and engine whirring in Jumana Manna’s Foragers next door, and so I leave to investigate. By stubbornly continuing to forage the wild plant akkoub in spite of Israeli preservation laws, the Arab inhabitants of Galilee and Jerusalem featured in Mannas video installation, are resisting attempts to alienate them from their land under the naturalized guise of ecology. One woman points out that since the outlawing of foraging, the plants which once thrived are disappearing faster.

When I return to look at the next of Ponce de León’s drawings Nunca regresaste, a pesar de que lo prometiste. Hemos decideo que dejaste de ser importante para nostros, my head is full of new ideas. Two legs, structured and upright, stand above the flattened page where a body calls up in protest from among the leaves.

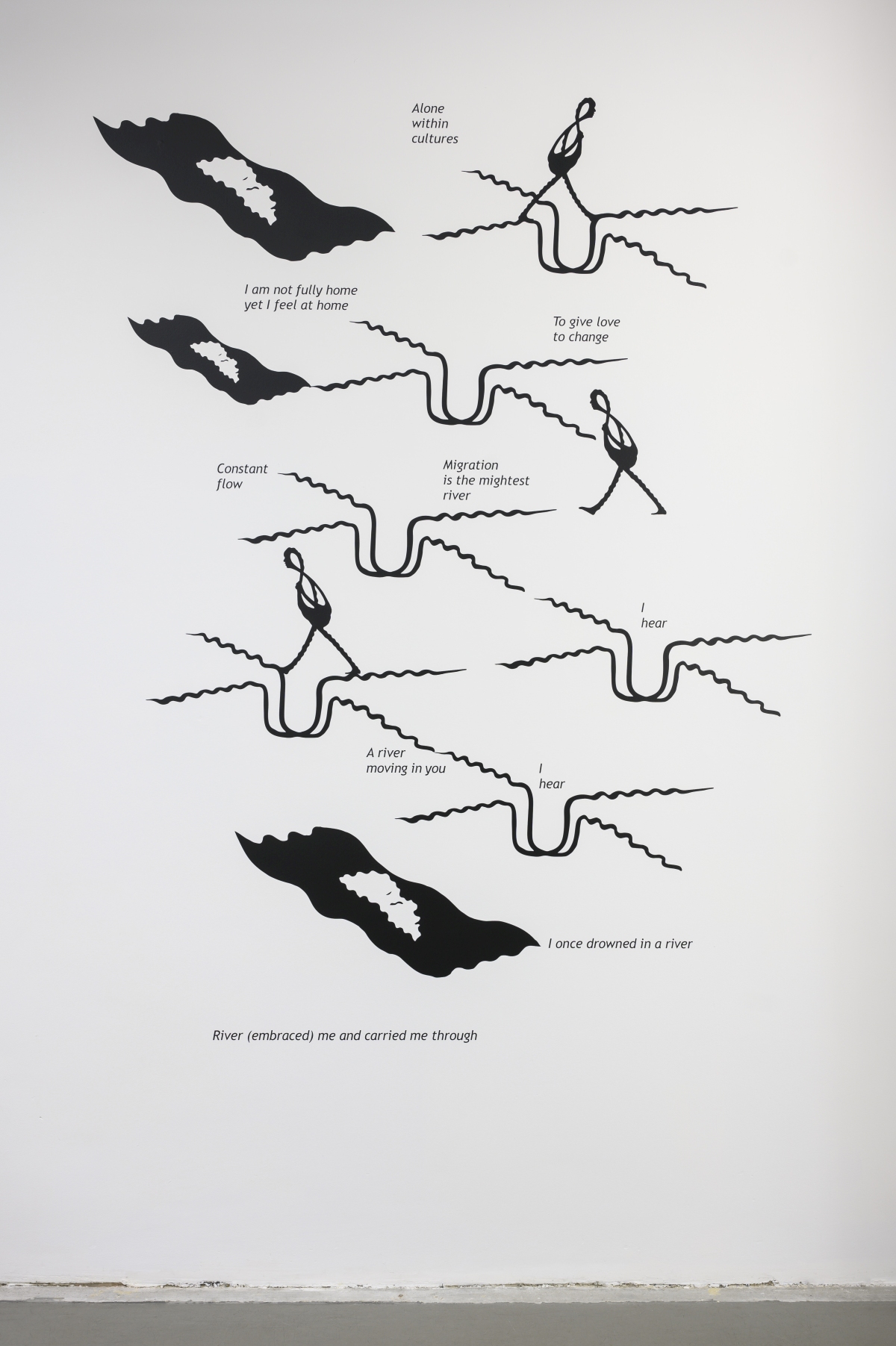

Rita Ponce de León, Personas abrazando ríos (Mensen die rivieren knuffelen), 2021, installatiebeeld No Linear Fucking Time, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2021–2022, foto: Tom Janssen

I enter and leave to Ponce de León’s mural Personas abrazando ríos. The words interject the viewing of other pieces, calling up to the balcony, across the room and through glass to the second floor. ‘I hear, I hear’, say the words on the wall, and the rippled lines like sound waves spread out into the room. Repeated symbols mark repeated rhythms and steps on a journey. They disconnect and reconnect themselves to different contexts. ‘We feel close intermittently.’

Jumana Manna, Foragers, 2022, installatiebeeld No Linear Fucking Time, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2021–2022, foto: Tom Janssen

Jumana Manna, Foragers, 2022, installatiebeeld No Linear Fucking Time, BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2021–2022, foto: Tom Janssen

In only one place do I find interruption taking over. The quiet pace of John Berger’s voice in Once Upon a Time is consistently disturbed by the sounds from auditorium behind. But I don’t feel annoyed by this.

I suppose this is how it is to be in time; to find your senses clouded by moments stretched out in all directions. Changed by memories of the past, visions of the future, simultaneous presents.

As I circulate through the space again and again, I find that through what first appeared to be instances of deception and interruption, I am starting to tangibly feel that sense of non-linearity the project posits as key in imagining anti-colonial presents. Leaving the exhibition, I have taken many pathways, followed repeated patterns, and interacted with different works all at once, each time escaping that linear fucking time. Experiences with time, especially as it is held here through concepts such as crip time, queer time, deep time and non-human time are as subjective as the paths we take through a space, as the order in which information might reach us, as the way each moment and interaction is coloured by all those around them. Imaginations that make these liveable times tangible can help us steer away from that all too destructive yet all too dominant force of hegemonic ‘true’ time.

No Linear Fucking Time is convened by BAK’s curator of public practice Rachael Rakes with artist-interlocutors Femke Herregraven, Jumana Manna, Claudia Martínez Garay, as well as writer Amelia Groom. The exhibition is on view at BAK, Utrecht until the 22nd of May, 2022. For more information (also about the gatherings held in relation to the exhibition), click here.

Cara Farnan

is a visual artist and educator