Dan Perjovschi (Fridericianum)

Rumble in the ruruHouse – on documenta fifteen and ruangrupa’s global art movement

ruangrupa’s documenta fifteen wants to provide the institution of art, including the documenta itself, with new social and activist foundations. Are they succeeding? Sjoukje van der Meulen and Max Bruinsma consider the pros and cons of this new global art movement envisioned by ruangrupa and whether the new discourse is truly open to public participation.

For days at the opening of the fifteenth documenta in Kassel, a Babylonian war of words raged over an “anti-Semitic work of art”. It concerned visual words on an enormous billboard – Taring Padi’s People’s Justice (2002) – that were anti-Semitic but not meant to be. Or perhaps they are, covertly packaged in a cartoon about military oppression in Indonesia, supported by global capitalism. Or not, but then the use of imagery shows a naive blindness to the conceptual history of certain anti-capitalist caricatures, such as that of “the rich Jew”. In the meantime, German public opinion has made up its mind: the billboard contains “eindeutig anti-Semitic connotations” (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung) and has therefore been removed from the Friederichsplatz in the city center. [1] The Documenta management and the artistic leadership, the Indonesian artists’ collective ruangruppa, have apologized and uttered a mea culpa: “The truth of the matter is that we collectively failed to spot the figure in the work, which is a character that evokes classical stereotypes of anti-Semitism. We acknowledge that this was our error.” [2]

The media storm over one work threatens to drown out the central story of this mega-exhibition. That story is about coming together and collaborating, diversity and tolerance, fighting against every form of oppression, exploitation and racism, learning from each other and respecting each other’s backgrounds and ideas. Peaceful sharing is the core artistic concept of this documenta. To formulate this new understanding of what art is or can be, new words are needed. The Indonesian collective ruangrupa finds those new words in their own language and culture as well as in other non-Western cultures.

ruangrupa was founded in 2000. The now internationally operating group is rooted in Indonesia, in particular Jakarta, and has been shaped by the historical political context of the end of President Suharto’s regime (1966-1998), the New Order. In the words of Ade Darmawan, one of the group’s founders, “In the late 1990s, we were art school activists, but only a very small part of a larger wave of protests.” [3] Darmawan is referring to Indonesia’s “Reformarsi,” the widespread (student) movement that was crucial to the fall of the regime after 32 years.

Gudskull (Fridericianum)

At documenta there seems to be nothing less than a paradigm shift

Gudskull (Fridericianum)

Thomas Berghuis noted as early as 2011 in Third Text that ruangrupa not only created a new platform, but also initiated an entirely new infrastructure for artistic and cultural practices, developing new ideas for socially engaged art and connecting with a network that reached far beyond Indonesia. [4]

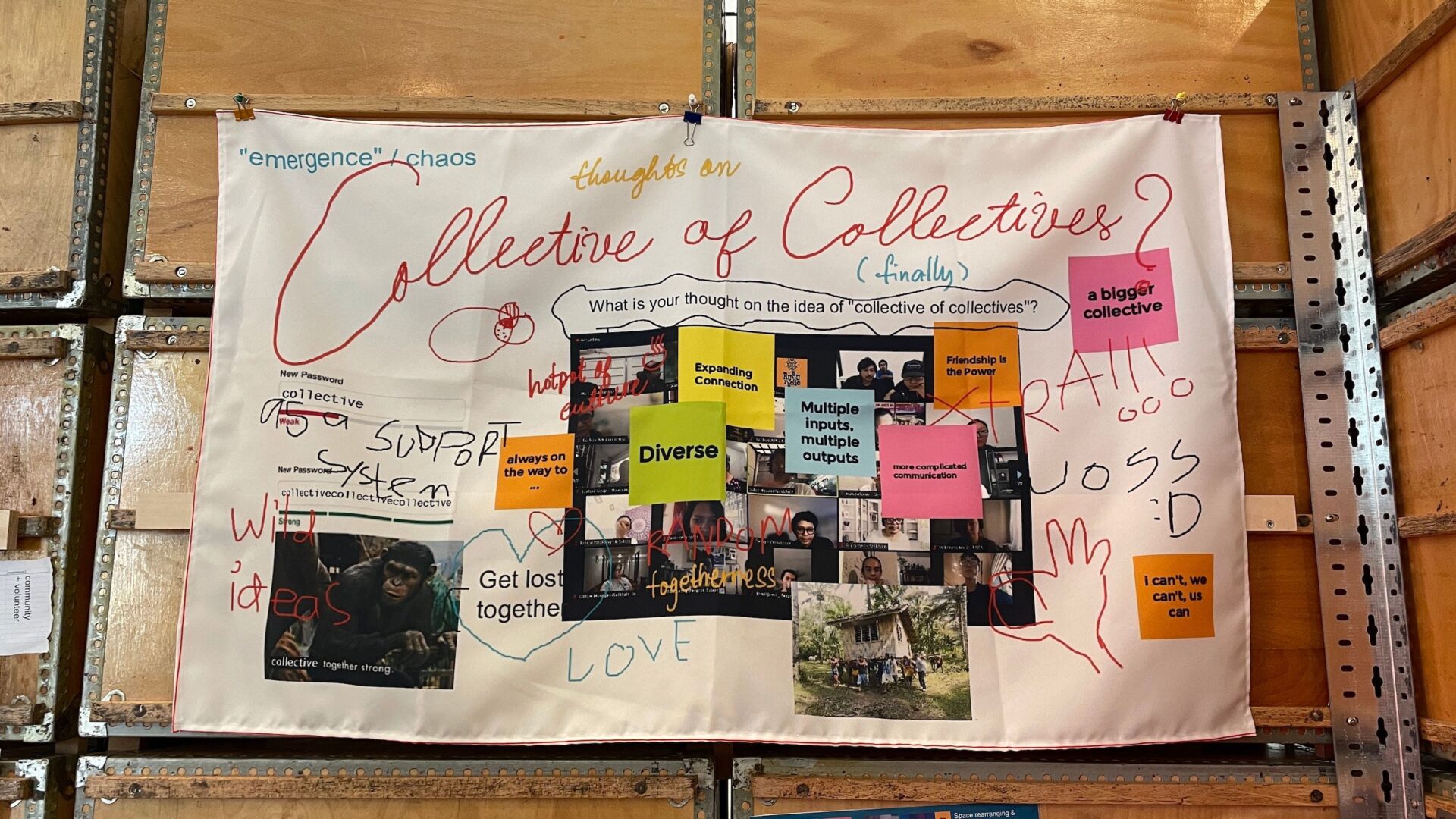

The breakthrough to the Western art world came a few years later, when the Indonesian artists’ collective was invited as curatorial team for Sonsbeek 2016, the international sculpture exhibition in Arnhem, the Netherlands. The exhibition, called Transaction, contained many of the ingredients of documenta fifteen: as in Kassel, there was also a ruruHuis in Arnhem, which acted as the social heart and creative brain of the exhibition, and there, too, the focus was on artist collectives and participation of the public and the local population, aimed at discussion, interaction and social engagement. The big difference between Sonsbeek and documenta, however, is the scale and the programmatic, almost ideological way in which the “collective of collectives” is given shape and literal space in Kassel: whilst at Sonsbeek one could still think of a private preference for a new social trend in art, which Claire Bishop already in 2004 called “The Social Turn”, [5] at documenta there seems to be nothing less than a paradigm shift and a global movement in art.

Lumbung

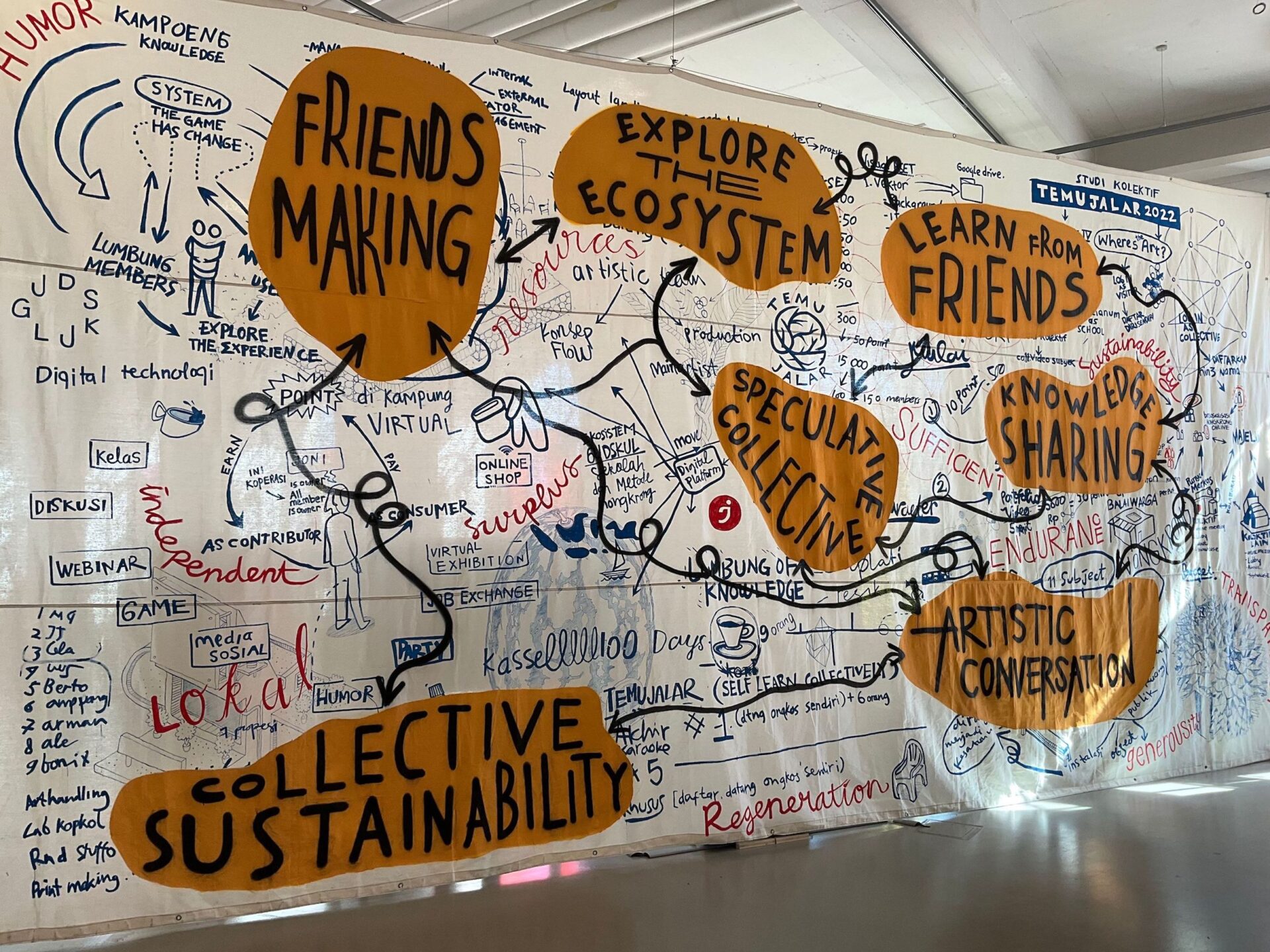

A paradigm shift requires new concepts. Consistent with their ideology, ruangrupa derives the new vocabulary from various cultures and shares it in what could be called the lumbung of language. Lumbung is the Indonesian term for a rice barn in which a village community collectively stores and manages the harvest. In a broader sense, lumbung represents social values such as communality, sustainability, and the sharing of knowledge and resources. Throughout documenta, there are flow charts and placards that recall this key concept. Another central Indonesian term is nongkrong, which stands for social and casual gathering, talking, eating and exchanging ideas. [6]

But also related terms from non-Indonesian cultures are re-minted, such as rancheár, an Argentine term for spending time together without high expectations, similar to nongkrong – hanging out would be a good contemporary English equivalent. Furthermore, we learn about bulon, a term which in Nigerian culture denotes a physical and multifunctional space of social forms full of symbolic layers of meaning, and about the Malian maaya concept that refers to the relationship between collective and individual and the related maaya values of generosity, self-knowledge and humorous kinship.

All in all it seems that this new vocabulary wants to offer an alternative, conceived primarily from the global south, to the dominant Western conception of art that stems from a centuries-long Eurocentric and colonial history of cultural inclusion and exclusion. Such an alternative idiom also implies a radically ‘different’ documenta – the beating heart of precisely this Western concept of art. But in addition to all the new words – verbal immigrants in an old Western discourse – an art-indigenous term also comes to mind: institutional critique seems to be a key concept for this documenta. ruangrupa questions both the format and the institutional frameworks of the documenta from the inside, which gives this fifteenth edition an ambiguous character – the artistic leadership is qualitate qua insider but continues to act as an outsider. As art critic Karen Archey recently suggested in After Institutions, “I would argue that there is a neo-avant-garde impulse to tear down institutions as we knew them from a hybrid internal-external position, and thus the contemporary position of Institutional Critique is defined by this insider-outsider relationship.” [7]

As a result, documenta fifteen is an exhibition full of paradoxes: it takes place in a German art city, but at the same time wants to do away with the dominance of Western art (cities); it opposes liberal capitalism, but at the same time has a budget unparalleled in the art world; it is an exhibition that actually does not want to be an exhibition, but a collaboration between creative collectives for a better world. One cannot help but recall a seventies concept: “repressive tolerance”. The term was coined in 1965 by Herbert Marcuse [8] and has been used in social-critical circles since 1968 mainly to describe the strategic suppression of dissent by the powers that be; criticism is given space so that it can then be encapsulated and defused. In the context of this documenta one can ask whether a similar strategy is being used here; give the opposition all the space it needs (and a wad of money) and they will adapt. Or is there also at documenta as an institution a genuine desire to do more justice to the great variety of voices that by now characterize the international art discourse, even if these voices contradict some of the central notions of this very discourse?

Perhaps the most important consequence of ruangrupa’s redefinition of the concept of art is the shift in focus from the autonomous artistic individual (formerly the ‘genius artist’) to collectives of more or less anonymous members and participants who operate in ever-changing contexts and who, in ruangrupa’s terminology, are increasingly aware of the broader social, economic and ecological ‘ekosistems’ in which they operate. Such systems of interdependence and agency extend from existing human and non-human actors to social and economic structures and the (fragile) planet as a whole. One feels the influence of Bruno Latour’s “Actor Network” theory here.

The emphasis here is less on ‘the outcome’ (formerly ‘the work of art’) than on ‘the process’, on how the various members of the collective interact with each other, how their work is created in dialogue and collaboration with local communities or an international network of like-minded people and which obstacles and challenges have been overcome. That is the work of art: the process of action and what Bishop qualified in 2006 as “the creative rewards of collaborative activity.” [9] What we see as audience is the documentation of that action, captured in photographs, drawn diagrams, flow charts, mood boards, videos, documentary films, magazines, websites and archives. The idea is that this collaborative action is nurtured and shared by “the people” to offer an alternative to the capitalist system which, applied to the arts, is primarily concerned with individual authorship and marketable artworks. A paradigm shift, therefore, with art in a vanguard role. Or in the words of Charles Esche, director of the Van Abbemuseum and member of the committee that selected the curatorial team for documenta 15: “It is up to the art world to drive this major social transition. People have always needed each other to achieve anything.” [10]

An interesting split

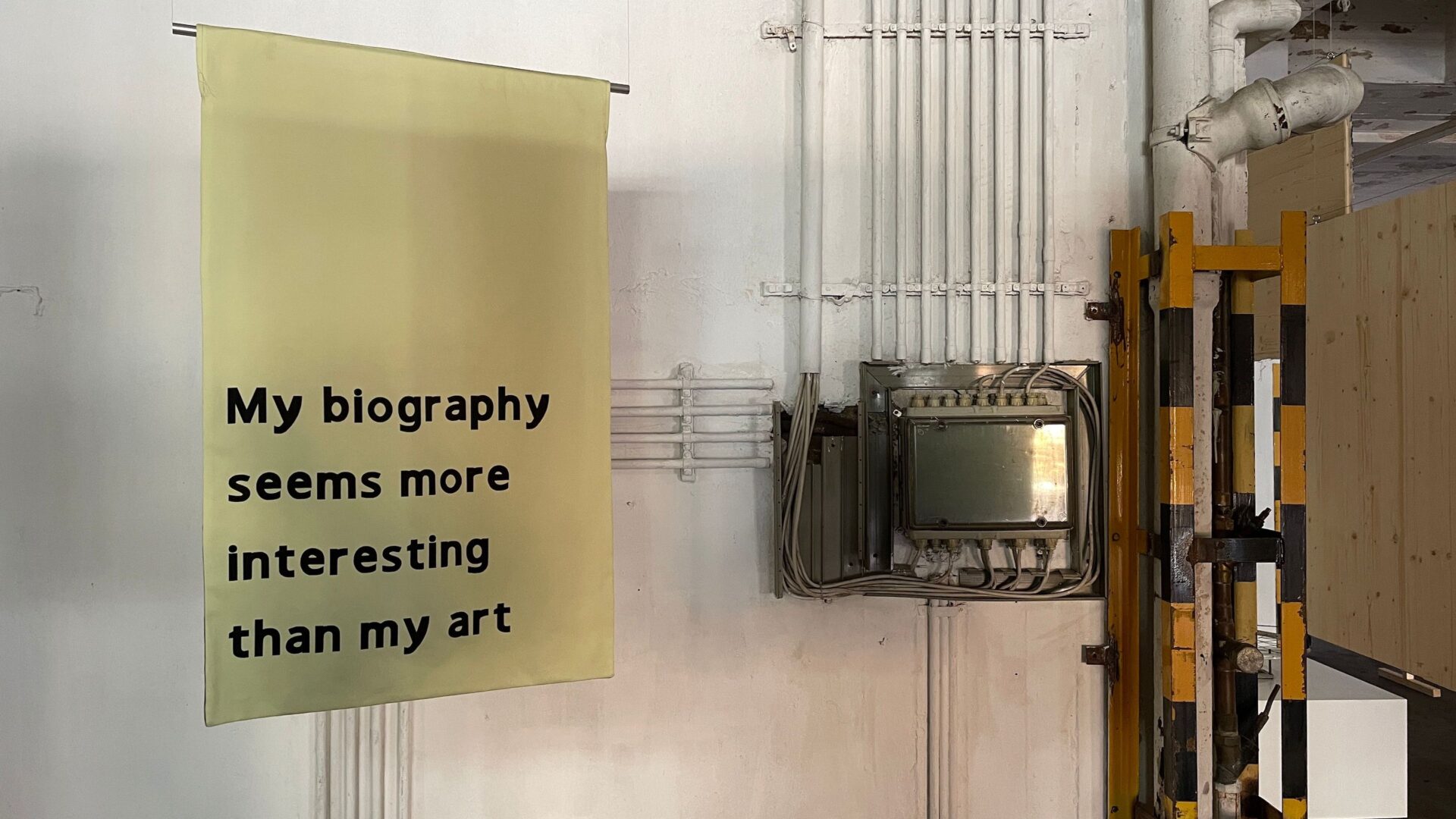

The focus on ‘social relevance’ (to dust off another seventies term) does have the effect of rather blurring the lines between art, social design, social work, political activism and public educational campaigns in Kassel. At the museum Fridericianum – once a hallowed repository of masterpieces – now a kind of market for master classes takes place, the “Fridskul.” No fewer than eleven collectives fill a large part of the museum with “collaborative pedagogical projects.” Through workshops, a kitchen, a “knowledge market,” games and karaoke, “experience-based learning” is offered (a pedagogical model known in Jakarta as Gudskul). One of the “exhibited” collectives is *foundationClass who proclaim their didactic model of “(un)learning” on banners in both the stairwell of this museum and in the rooms of the old industrial building at Hafenstraße 76. The model produces an interesting split: on the one hand it insists on the importance of collective action and cooperation and on the other it focuses on the urgency of one’s own individual identity. Deeply individual expression as group identity; the paradox is summarized on one of the banners as follows: “We work collectively to realize the project of the individual, reclaim our subjectivity(s) and empower each other in the process of becoming who we are.”

*foundationClass*collective (Hafenstrass 76)

At the museum Fridericianum – once a hallowed repository of masterpieces – now a kind of market for master classes takes place, the “Fridskul”

*foundationClass*collective (Hafenstrasse 76)

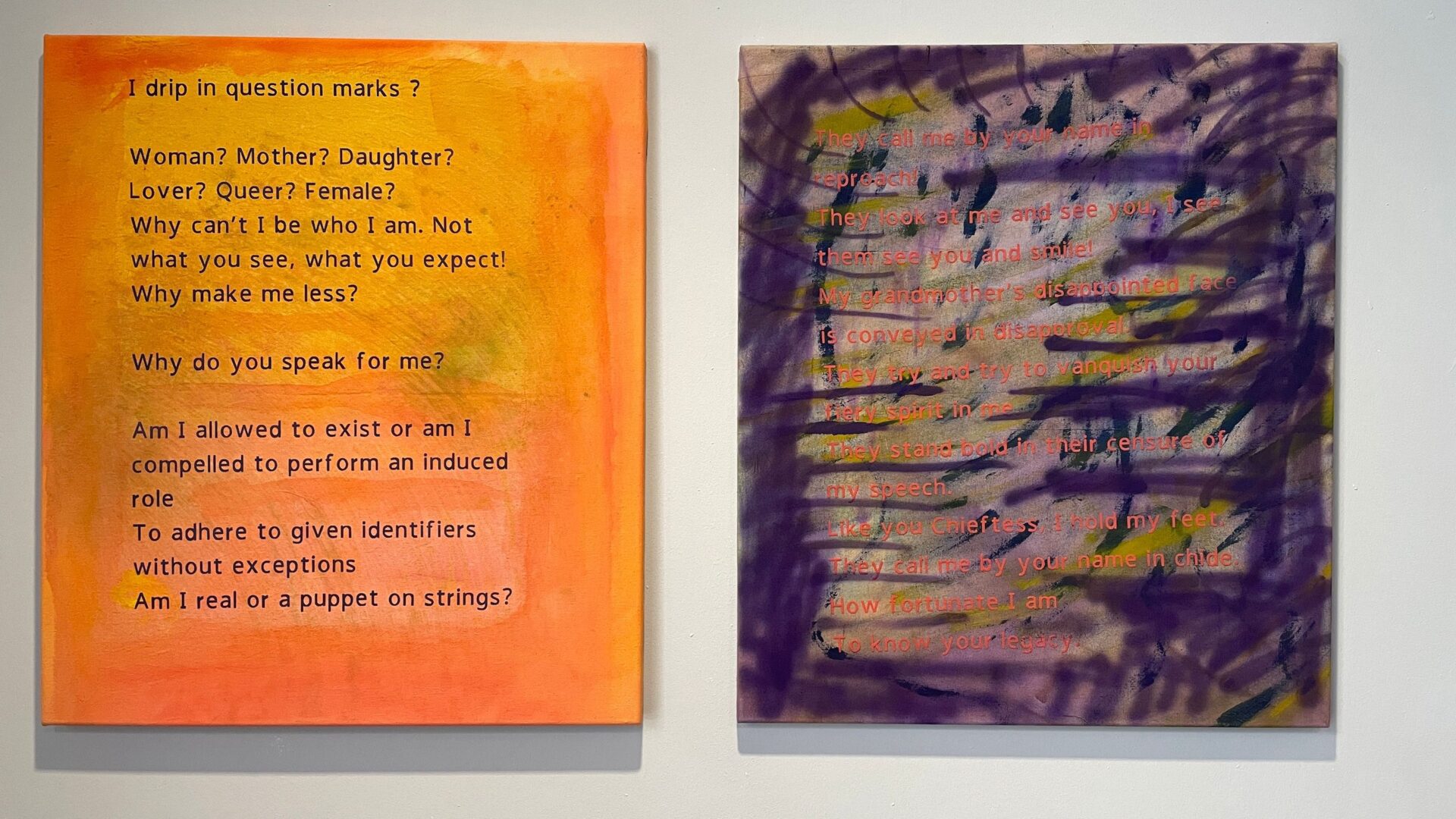

At equally tense odds are the emphasis on one’s own biography and the desire to break away from the standard ways in which that biography is often read. The personal histories of artists and the personal stories they document about cultural identity, migration, ‘queerness,’ neurodiversity, gender, social roles, lead to laments like, “I drip in question marks? / Woman? Mother? Daughter? / Lover? Queer? Female / Why can’t I be who I am.” All these words are both stigmata (if the outside world sticks them on you) and sources of proud identification (if you choose them yourself).

documenta fifteen is steeped in such identity politics, both on an individual and a group level. At the Fridericianum, for example, the OFF-Biennale Budapest focuses on the art of the Roma, which is underexposed throughout Europe, and is pushing for a new art institute: RomaMoMA. In Gayatri Spivak’s now classic essay ‘Can the Subaltern Speak?’ (1988), [11] she argues that formerly colonized populations in the Global South, women in particular, are made difficult if not impossible to “speak for themselves,” by a complex of historical, ideological, and colonial factors. In the contemporary debate on inclusion and diversity, and in theories of gender, queerness, and intersectionality, this understanding has been further developed into a radical refusal to let the other speak for you any longer.

Thus, the entire documenta is essentially thought of as an ekosistem of safe spaces within which lumbung participants can experience the nongkrong of learning, sharing, hanging out, chatting, making, eating, and being themselves together. Nothing is required, everything is allowed, and there is an emergency button for when someone crosses the boundaries during discussions – “everything stops for 5 minutes.” It often has a high Flower Power quotient that is solidified in countless card and board games, in didactic diagrams, in boxes full of post-its, notes, souvenirs of meetings, cards of trajectories and networks and other small and large objects. Together all these fragments form an archive of “their working process and their transformation from their original meeting to the present,” as La Tabebh puts it. [12] This collective of eight collectives spread across five (mostly) Asian countries and three time zones, is part of the Gudskul collective at the Fridericianum, which has been renamed Fridskul. The shared core objective is “co-learning, developing collective-based artistic practices, and art-making with a focus on collaboration.”

What exactly has been learned, and how this is expressed in concrete work, remains unclear. That is a serious problem with this documenta: that all those ‘archives’ of artistic practices usually lack proper access. One sees a great deal of documentation, but it is unclear how this material is related and often what it is actually about. As a viewer, you can speculate about the meaning of a card with an image of Da Vinci’s Last Supper, around which the text ‘TOO MANY ME / IN COLLECTIVE’ is typed – the installation itself does not provide an answer. And although such indeterminacy is a core value of contemporary art, you would expect documentation and ‘archives’ in a didactic context to be a bit more enlightening.

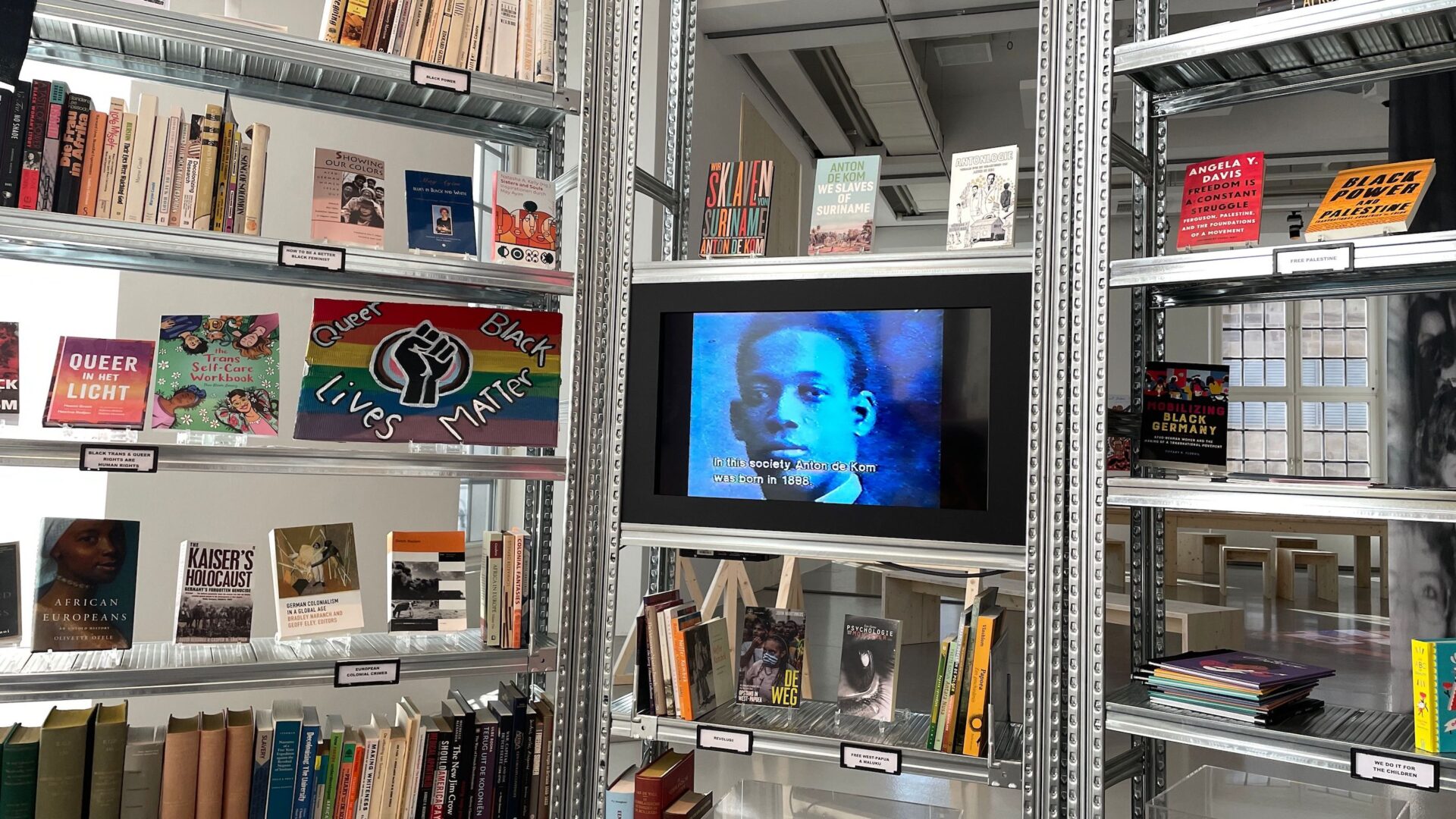

Another example is the installation of the Dutch Black Archives, also in the Fridericianum. Actually, the presentation offers little more than an enriched context around a very informative documentary film about Anton de Kom, resistance fighter and author of the groundbreaking anti-colonial book We Slaves of Surinam (1934). Woven around the monitor in stands and display cases is a small library of books and images about “a Black radical tradition and stories of transnational solidarity” with slogans like “Queer Black Lives Matter” and “White Silence = Violence.” The installation is clearly not intended as an (autonomous) work of art, and as a documentary exhibition it merely tips the subject – though one can learn much from the books displayed in the cabinet. Other archives in the same hall on the first floor of the Fridericianum have similar shortcomings, like the presentation of the Hong Kong Asia Art Archive: six monitors stacked on top of each other, showing historical videos of Chinese avant-garde artists, without any context. Already known to insiders of Chinese performance art since the 1990s, but impossible to follow for the unprepared audience.

The Black Archives

What exactly has been learned, and how this is expressed in concrete work, remains unclear. That is a serious problem with this documenta: that all those ‘archives’ of artistic practices usually lack proper access

Likewise, more installations in Kassel are unbalanced, or riven: the contributions on the one hand have to look artistic or at least documentary, but on the other, they also want to convey a very clear, often activist message. Time and again, the result is an ad-hoc slogan-like summary of good intentions, unless you make the effort to actually delve into the material on offer and forge connections yourself. This is actually not to be expected from the average exhibition visitor, who consequently feels a bit neglected in Kassel. The participants in the lumbung clearly benefit from the fact that their nongkrong has been given a physical location for a hundred days, but the acclaimed participation is generally limited to looking at loose fragments of a very complex network of processes, spread across many locations in the city. However, visitors feel and see that the participants of the artistic collectives expressly expect them to participate socially as well. Bill Cooke and Uma Kothari have pointed out before that the fashionable universal rhetoric of participation, if taken too far by activists and others, can take its own coercive, even tyrannical forms. [13]

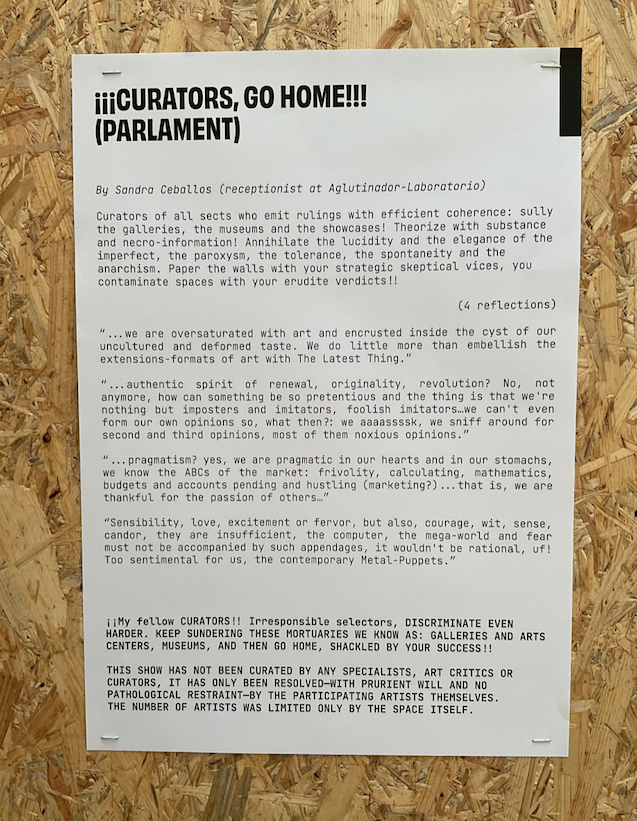

Exceptions are some large installations in the documenta-Halle. INSTAR (The Hannah Arendt Institute of Artivism) deploys the “deliberate and tactical use of the white cube [of the exhibition pavilion] as an alienated space to confer value and visibility on practices that have been distorted and/or erased by the Cuban regime.” Here, the visual and spatial means of contemporary art are effectively mobilized to present an “open archive” on repression of cultural diversity and artistic autonomy by authoritarian regimes such as the Cuban one. Here, too, a certain ambivalence regarding the Western-oriented art world – that alienated space – culminates in the manifesto “Curators Go Home!” Specialists, critics and curators should stay out: “Curators of all sects who emit rulings with efficient coherence: sully the galleries, the museums and the showcases!” The artists will do it themselves.

Curators Go Home

Instar (documenta-Halle)

Another large installation in the documenta-Halle is by Britto Arts Trust from Bangladesh, who have set up a kind of bazaar with provisions. In workshops in Dhaka the packaging was copied after existing models in ceramics, embroidery and crochet, metal and paper, but with small critical additions. For example, organic food is “100% lie” and genetically engineered peppers are (organic) hand grenades. Around the bazaar constructed from corrugated iron, Britto (“Circle” in Bangla) presents Bengali films on food, hunger and war, and outside, under bamboo shelters, a “Kitchen Garden” has been set up where traditional recipes and stories are shared. The whole thing is a solid and well-documented but also humorous critique of the “massive commercialization of food” and the importance of communal food production, in harmony with local nature and culture.

Britto Arts Trust (detail) (documenta-Halle)

Britto Arts Trust (detail) (documenta-Halle)

Britto Arts Trust (in front of the documenta-Halle)

Other locations

Apart from two of the main locations, the paradigm shift at documenta fifteen can also be seen in the choice of other locations. Over the past thirty years, there have been a few constants: in addition to the Fridericianum (which has served as the main building since documenta’s inception in 1955) and the documenta-Halle (an addition by Jan Hoet in 1992), also the Orangerie, the Neue Galerie and the Hauptbahnhof (in use since Catherine David’s documenta in 1997). Again, the Fridericianum and the documenta-Halle feel like the actual artistic centers, more so than the ruruHaus located in a former department store on nearby Königsstraße. However, many other ‘traditional’ documenta buildings are not in use. The Orangerie, the Neue Galerie, and the Hauptbahnhof function at most as orientation points for scattered works in public space. ruangrupa fans out to other parts of Kassel: to the eastern side of the Fulda for example (locations Hafenstraße 76, Hallenbad Ost, Hübner Areal) and to the north. In order for visitors to cover these greater distances in an ecologically sustainable way, documenta gives them free tickets for public transportation. The atmosphere in all these places is the same: everywhere the emphasis is on the social practice of cooperation and participation. Not the objects are central, but the interaction between the makers and their social environment, grounded in social themes and in the expanded tradition of relational art, once introduced by French art critic Nicolas Bourriaud.

spaces for nongkrong that remained tentatively empty during the opening days

As a visitor, you eventually become a little weary at the sight of yet more spaces with well-intentioned, inviting but de facto often empty rows of chairs, cozy tea corners and mimicked living rooms, where as often nothing happens as something. However, the social issues raised in these participatory spaces remain interesting. And if they are well documented, represented, imagined and contextualized, they are sure to benefit you. For example, in the Hübner Areal, there is the living room set-up of Trampoline House, which provides insight into the abuses surrounding asylum applications in Denmark through text, images and documentaries. Hafenstraße 76 features the video installation by Lebanese artist Marwa Arsenios, who argues in a voice-over over beautiful images of nature how our current conceptions of property are (or will become) completely untenable in the emergency of the climate crisis. Her persuasive plea for a renewed appreciation of the ancient concept of the “commons” – called “social waqf” or “mashaa” in this project about a Lebanese quarry – fits perfectly into this documenta.

In the art bazaar-like setup of documenta fifteen, the artworks and installations that create or claim their own (mobile) space are the ones that most remain in one’s mind. These projects, collective or otherwise, provide the visitor with space for individual concentration and reflection, amidst the cheerful but also cluttered venues in which the call for participation sometimes seems somewhat forced. A good example of such a work of art that invites reflection is the hybrid media installation by Nguyễn Trinh Thi in the Rondell, a defense tower from 1523 on the Fulda River. Inside, in the dark vault, shadows of real chili plants are projected onto the damp walls. They light up as rarefied sounds of wind instruments are streamed from Vietnam into the old dungeon.

The hut of textile bales, made by The Nest Collective from Nairobi also stands alone, as a curious monument on the vast field in front of the Orangery. Inside the hut, a video has been installed explaining how the West dumps discarded clothing in Africa with supposedly good intentions; in fact, the continent benefits very little from it. A little further on, the black tent of Chinese duo Cao Minghao and Chen Jianjun stands like a stray yurt. Cao and Chen are using artistic research to make ecological improvements to the water systems on the parched lands that threaten herders and yaks in the mountains of Sichuan. In the traditional nomadic tent made of yak hair, new grass is grown locally for the Kassel pasture, while workshops take place there as well. A video tells more about the project, which is further explored in video installations at Hafenstraße 76.

The Nest Collective (Karlswiese)

In the art bazaar-like setup of documenta fifteen, the artworks and installations that create or claim their own (mobile) space are the ones that most remain in one’s mind

Cao Minghao en Chen Jianjun (Karlswiese)

Más Arte Más Acción (Karlswiese)

Somewhat isolated is also the quirky compound of the Colombian collective Más Arte Más Acción, which borrowed a heavy truck from Dutch artist Atelier Joep van Lieshout (AVL). The “Werner” is a mining behemoth that can handle any terrain, converted by AVL into an autonomous action and information center. Next to it are a tent in which documentaries are shown and a meeting table around an impressive tree, where artists, scientists and activists come together to discuss social and environmental issues.

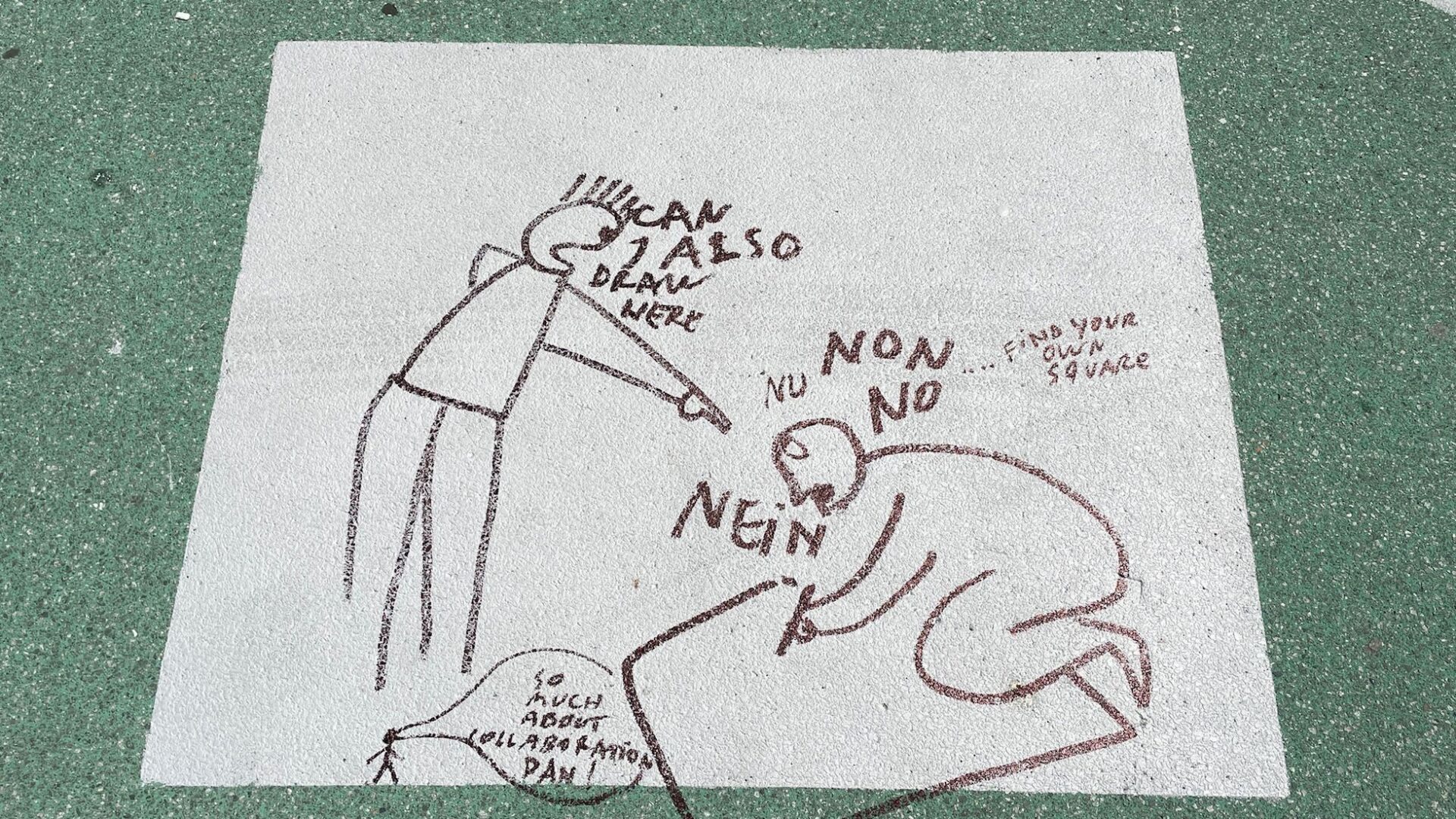

And then there is the “horizontal newspaper” of Romanian artist Dan Perjovschi, who leaves his humorous, critical drawings on current social issues on the square in front of the Hauptbahnhof every day and invites the public to join in other drawing frames – as long as they don’t touch his drawings. The columns of the Fridericianum are also chalked full of his sometimes cutting and also self-critical comments. Inside, in the hall, he has made his own witty and downplayed version of the vast array of logos of documenta-supporting institutions and companies.

Dan Perjovski, Horizontal Newspaper, 2022 (Rainer Dierichs Platz)

Dan Perjovski, Horizontal Newspaper, 2022 (Rainer Dierichs Platz)

Truly participatory?

Perjovschi is one of the few individual “authors” at this fifteenth documenta, which primarily celebrates collectivity. ruangrupa’s program, as should be obvious by now, can be read as the abolition of the individual artist concept in favor of a concept of art-as-community-action. That idea is presented here with such aplomb that the term “trend” no longer fits. It seems that the global avant-garde of socially engaged cultural workers wants to put the entire international art world on a new footing. With Esche’s previously quoted remark in mind, one can have little objection to that. But at the same time, we get the feeling that a new dogma is being preached here that barely acknowledges its own inner contradictions and within which only artists like Perjovschi (who secretly takes the collective model to task), survive “independently”. The new art model stretches the notion of “art” so far that it virtually seems to coincide with the social domain in general. That can be inspiring and liberating, as Domeniek Ruyters has already observed on this website, but on the other hand it raises the question of what ‘art’ as a more or less specific medium of social action still means. Moreover, one might ask: does the notion of ‘art-as-activism’, based on an underlying collectivist-identarian ideology, necessarily contribute to reducing the strong polarities in today’s society? The commotion at the beginning of this documenta underscores the urgency of that question. It also illustrates how well-intentioned ‘dissenting voices’ can evoke strong reactions from a (cultural) establishment that feels threatened.

The split identified earlier between identity politics and collectivity can both hinder and promote open exchange. And the new jargon introduced by ruangrupa can also become a language for the initiated that excludes others. On the one hand the relationship between art and the public is romanticized at this documenta – everybody together! – but in the practice of the mega-exhibition, visitors are still more or less passive witnesses, mainly, to the nongkrong of 1,700 artists from all parts of the world, celebrating their togetherness and collective action. Yes, much of the work reflects the collaboration and shared creativity and social action of artists and “local communities”. But how to take the visitors in Kassel out of their internalized role of spectator and at the same time not force them into a straitjacket of preconceived participation? The “deeply individual” individual may not want to do things together all the time at all.

On the one hand the relationship between art and the public is romanticized at this documenta – everybody together! – but in the practice of the mega-exhibition, visitors are still more or less passive witnesses, mainly, to the nongkrong of 1,700 artists from all parts of the world, celebrating their togetherness and collective action

We visited documenta fifteen during the press opening days and the subsequent opening day for the public. The fact that the participation of the hundreds of ambling journalists and critics did not yet get off the ground in the first week was perhaps also due to the fact that the announced ‘discussions’ or ‘conversations’ often amounted to parties of like-minded people, or could not be followed due to the use of languages other than English, or simply did not take place. On Saturday the first curious visitors came en masse to see what had been made, entirely in accordance with ruangrupa’s script, for whom the public opening is more important than the press opening. They often walked somewhat estranged through the halls and along the ‘participatory spaces’. Perhaps it was unfamiliarity on both sides. But as a whole – as a design, as a ‘master plan’ – the exhibition that does not want to be an exhibition, and that wants to provide the institution of art, including documenta itself, with new social and activist foundations, in our view still provides too few tools for real audience participation. The remaining time of the hundred days will show whether all the collaborative projects, reflection spaces and cozy sitting corners will lead to more and more interesting interaction than simply watching a new, global movement in art also conquer ‘the west’.

Max Bruinsma is an art and design critic and media producer. He has taught visual storytelling at various art academies in the Netherlands and abroad.

Sjoukje van der Meulen (PhD, Columbia University) is associate professor at Utrecht University, specializing in modern and contemporary art.

All photos were taken by the authors.

[1] See: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/kunst-und-architektur/documenta/streit-um-documenta-kasseler-ob-droht-bund-mit-alleingang-18138188-p2.html

[2] ruangrupa and the Artistic Team, “statement on dismantling ‘People’s Justice’,” https://documenta-fifteen.de/news/dismantling-peoples-justice/, visited June 23, 2022.

[3] The Collective Eye and ruangrupa, “The Collective Eye in Conversation with ruangrupa: Thoughts on Collective Practice” (Berlin: Distanz Verlag, 2022), 15.

[4] Thomas Berghuis, “Ruangrupa, What Could be ‘Art to Come’,” Third Text 25, no. 4 (2001): 395-407.

[5] Claire Bishop, “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents,” Artforum (February 2006): 178-183.

[6] This term is interpreted and contextualized by Kerstin Winking in the latest issue of Metropolis M, based on a conversation with members of ruangrupa. Kerstin Winking, “Talking about Nongkrong,” Metropolis M 43, no.3 (2022): 52-58.

[7] Karen Archey, After Institutions (Berlin: Floating Opera Press, 2022), 107.

[8] See: https://www.marcuse.org/herbert/publications/1960s/1965-repressive-tolerance-fulltext.html

[9] Bishop, “The Social Turn,” 178-179.

[10] Charles Esche, “On the Importance of the Collective, Global Relations, and the Danger of Utopia,” https://www.ammodo.org/reflecties/charles-esche/, accessed June 24, 2022.

[11] Gayatri Spivak’s “Can the Subaltern Speak?,” in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, eds. Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988), 271-313.

[12] All quotations not referred to in footnotes are statements by the artists themselves, either from the Documenta Short Guide or in venue texts at the Documenta.

[13] Bill Cooke and Bill Cooke and Uma Kothari, Participation: The New Tyranny (London, Zed Books, 2001)

Sjoukje van der Meulen & Max Bruinsma