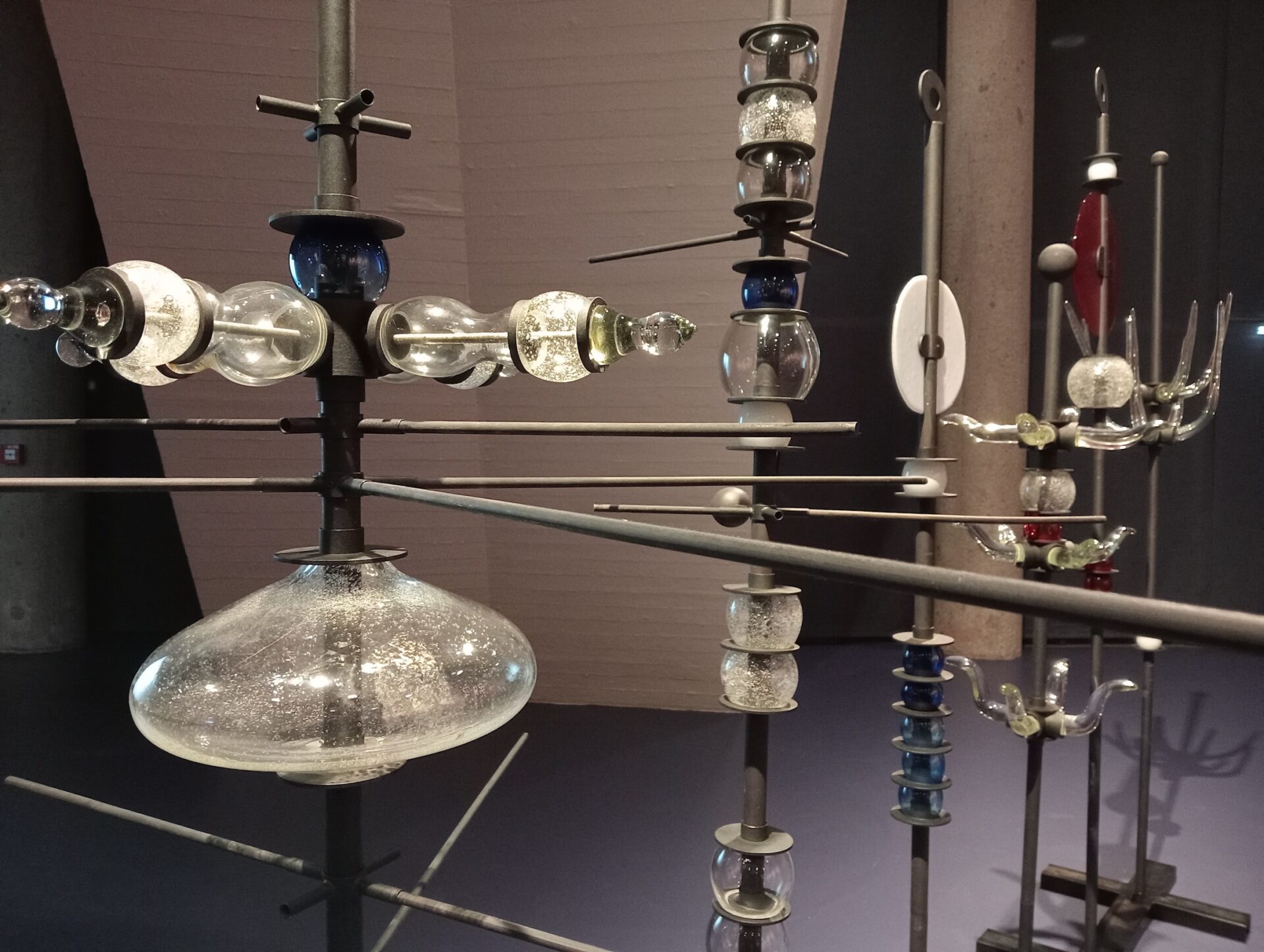

Xenia Kudrina, Black Ice (2014), Courtesy of the artist, installation view As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories. Fragments for a Geopoetics of North Eurasia, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), 2023. Exhibition Design: 2050+. Photo: Studio Bowie/HKW

A ‘geopoetical’ view on North Eurasian narratives

For their exhibition As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories. Fragments for a Geopoetics of North Eurasia, the curators at Haus der Kulturen der Welt have chosen not to give any background information, hoping to put the ‘poetic imagination’ of the visitors to work. Marga van Mechelen visits the exhibiton and reviews this ‘method of geopoetry’.

A new and ambitious team took office at Haus der Kulturen der Welt in Berlin earlier this year. In the Netherlands we know its director, Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, as the artistic director of the last Sonsbeek exhibition. Other well-known faces include Cosmin Costinas, senior curator at HKW, and Daniel Neugebauer, curator of cultural education and strategic partnerships. Costinas worked as a curator for de Appel in Amsterdam and BAK, basis for contemporary art in Utrecht, a while back. He was also director of Para Site Art Space, an art centre in Hong Kong, and co-curator of the tenth Shanghai Biennale, making him well versed in Asian contemporary art. Neugebauer studied in the Netherlands and worked at the Van Abbemuseum until 2018.

This new team aims to look critically at HKW and its history. The institution was gifted to Berlin by the United States in the middle of the Cold War, a couple of years before the construction of the wall. It was intended as a conference hall and functioned that way until 1989, when it became a cultural centre. Many now see it as a symbol of Western cultural hegemony, but this new team wants to start rewriting that history. They have already started doing so through a simple but effective intervention: they renamed all thirty-three spaces in the building. All of them now carry the names of women from all over the world. The largest space, the auditorium, is named after singer and human rights campaigner Miriam Makeba. However, most of the women were unknown to me. According to HKW, they all deserve a more prominent place in world history.

HKW’s commitment to rewriting history is reflected in their current exhibition As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories. Fragments for a Geopoetics of North Eurasia, which contains works by artists from the Ukraine, the Baltic States, Kyrgystan, Yakutia and every corner of the former Soviet Union. The accompanying manual contains a foreword by the director, which is titled ‘Die Welt durch das Prisma des Globalen Ostens betrachten’.

Jaanus Samma, Riga Postcards (2020), courtesy of the artist and Temnikova & Kasela Gallery, Exhibition view As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories. Fragments for a Geopoetics of North Eurasia, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), 2023. Exhibition Design: 2050+. Photo: Studio Bowie/HKW

Trying ‘to look at the world through the prism of the Global East’ seems fitting for a Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Yet rather than shedding light on the whole of the Global East, the exhibition, as its subtitle already indicates, limits itself to the area of North Eurasia. Most of the exhibiting artists live in post-Soviet countries. Some were born in the new era, others much earlier and even before the Second World War. HKW leads us through their works by grouping them in universal, seemingly timeless themes such as migration, homesickness, nostalgic longing, trauma and discrimination of for example queer sexualities (a topic addressed in the work Riga Postcards by Tallinn based artist Jaanus Samma). There are video performances of Kyrgyz artist Chingiz Aidorov, the Ukrainian Nikolay Karabinovych, the well-known Moldavian artist Pavel Brãila and Natalia Papaeva, descendant of the indigenous Buryat population in Southern Siberia.

HKW groups the artworks in universal, seemingly timeless themes such as migration, homesickness and discrimination of for example queer sexualities (a topic addressed in the work Riga Postcards by Tallinn based artist Jaanus Samma)

Exhibition view As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories. Fragments for a Geopoetics of North Eurasia, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), 2023. Exhibition Design: 2050+. Photo: Studio Bowie/HKW

Other works on view are tempera paintings of Estonian artist Ilmar Malin, etchings (mezzotint) of likewise Estonian artist Kaljo Põllu, glassware of Russian artist Aslan Goisum and textile works of, among others, the Tatar Nazilya Nagimova. Most of the works can be found in the three larger spaces on the ground floor, but some can also be found in parts of the building that are free to access and even outside, where about ten flags hang by Sergio Zevallos, Nikolay Karabinovych and others, all commissioned by HKW.

It’s only in the accompanying – and quite puzzling – catalogue that visitors can find information on the stories behind these works and the lives, ages and origins of artists who created them. In the rooms of HKW themselves, the curators have chosen not to give any background information. Following what they call ‘the method of geopoetry’, the curators want to put the ‘poetic imagination’ of the visitors to work. This, they believe, will help them gain better access to this part of the world and the fate of its inhabitants.

Following what they call ‘the method of geopoetry’, the curators want to put the ‘poetic imagination’ of the visitors to work. This, they believe, will help them gain better access to this part of the world and the fate of its inhabitants.

The idea of enabling open-minded encounters with the work, uninformed by any historical context, is not new. It was at the heart of Art Appreciation, a method dating back to the early twentieth century, and has been criticized several times later on. In my review[1] of Harald Szeemann’s exhibition A-Historical Soundings in Museum Boijmans van Beuningen I already criticized this curatorial approach. Here at HKW, the decision to present the works in an a-historical, a-sociological and essentially a-political manner echoes another exhibition made by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. In Arnhem, he also allowed the public to freely roam around in the park and the other exhibition spaces during the last edition of the biennale. Among other things, this made that the exhibition as a whole ultimately fell apart.

Oddly, the complete lack of information in the room of HKW themselves stands in stark contrast with the information given in the accompanying manual, which primarily centres on the biographies of the artists. These extensive stories, most of them written by Timor Zolotoev, are also accessible online.

Reading the manual, I find out that the man I see sowing mattresses together in Chingiz Aidorov’s video Yπumka (Cnupaπb) or Snail/ (Spiral) (2021) is the artist himself, who is a former migrant worker. Born in Kyrgyzstan, the man worked in Russia, under sever conditions. He had to clear his mattress when he got up to make room for the next guest worker, usually seven days a week, month after month. By selling old matresses he was able to buy the new ones we see in the video.

Natalia Papaeva, Yokhor (2018), installation view As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories. Fragments for a Geopoetics of North Eurasia, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), 2023. Exhibition Design: 2050+. Photo: the author

I also find out that the outbursts of frustration and anger of artist Natalia Papaeva, documented in her video Yokhor (2018), were actually desperate attempts to hold on to her native language. Papaeva’s screaming is so intense, that in the eight hours I spent in the exhibition they only let the sound on for a few minutes.

Reading the manual, I find out that the outbursts of frustration and anger of artist Natalia Papaeva, documented in her video Yokhor (2018), were actually desperate attempts to hold on to her native language

Xenia Kudrina, Black Ice (2014), Courtesy of the artist, installation view As Though We Hid the Sun in a Sea of Stories. Fragments for a Geopoetics of North Eurasia, Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW), 2023. Exhibition Design: 2050+. Photo: the author

Moreover, the woman simulating playing a keyboard instrument in a barren landscape in the video Ici et Ailleurs (2023) of Karabinovych turns out to be the artist’s mother, who has fled from Ukraine and can no longer practice her profession as an organist and music teacher.

I can go on. Seeing the steel and glass of totem poles after having read the manual, I know that despite their cold appearance, Yakutian artist Xenia Kudrina attributes many warm meanings to them. And looking once more at the beamed projection on the wall of a black snail-like shape against a fiery red background, I now know that this is actually a document of an in tempera painted sun, made in the pre-digital era by Ilmar Malin, born in Tartu in 1924.

Re-reading the title of the exhibition, ‘Als hätten die Sonne verschartt im Meer der Geschichten’ (or: ‘As if the sun had been buried in the sea of stories’), I remember a couple of works that depicted suns. Slowly some associations and connotations start to arise between the works. But on a first visit, the lack of information prohibits viewers to completely engage with the works. Looking at the multicoloured textile collages of Polish artist Malgorzata Mirga-Tas, I wonder: will visitors who did not visit the last Venice Biennale realize that these are Roma people?

In the end, the poetics of the exhibition itself lies primarily in its design. It’s a ‘good looking’ exhibition that tries to open your eyes to many lesser known regions and generations. If anything, the curators have demonstrated that this part of the world deserves a place in their house of world cultures.

The exhibition runs until January 14, as does the exhibition Exercises in Transformation by Sergio Zevallos

[1] See ‘Astray from History: Three Exploratory Exhibitions’, Manifesta Journal, no. 9, 2009/2010

Marga van Mechelen