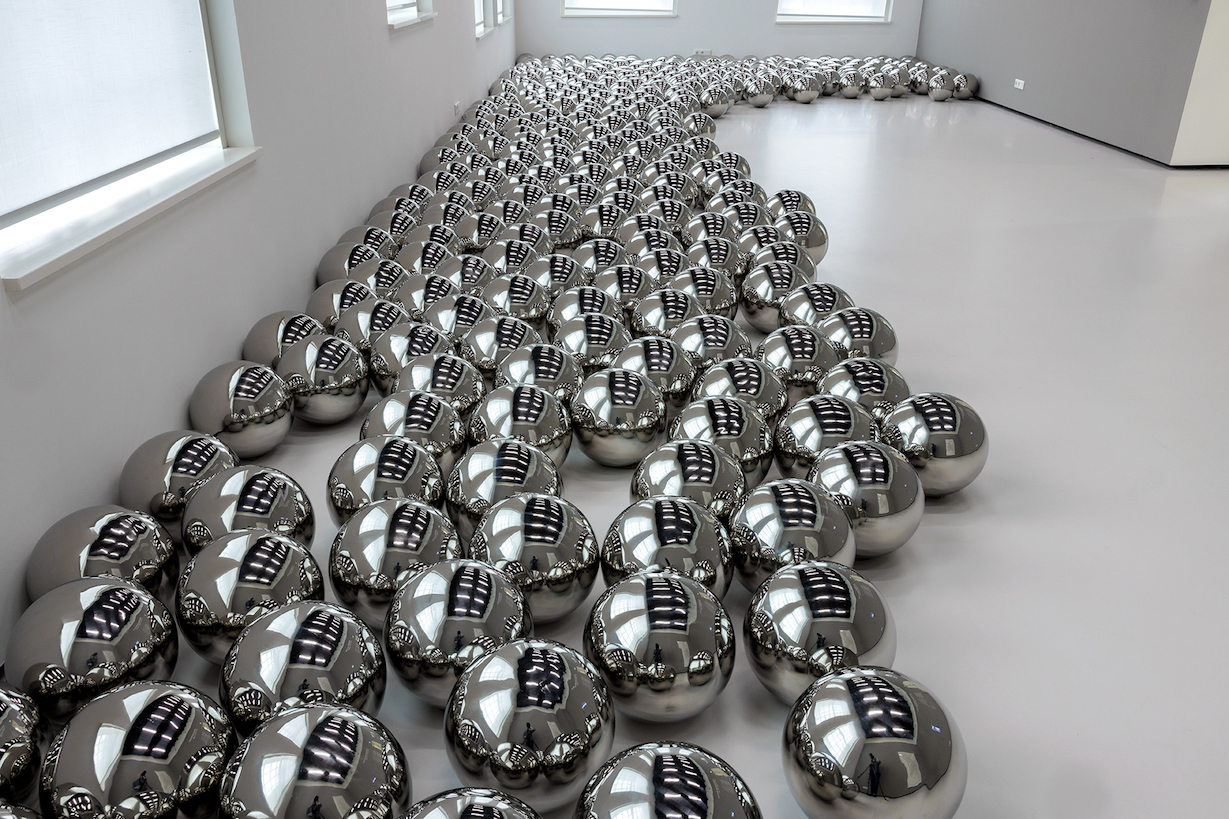

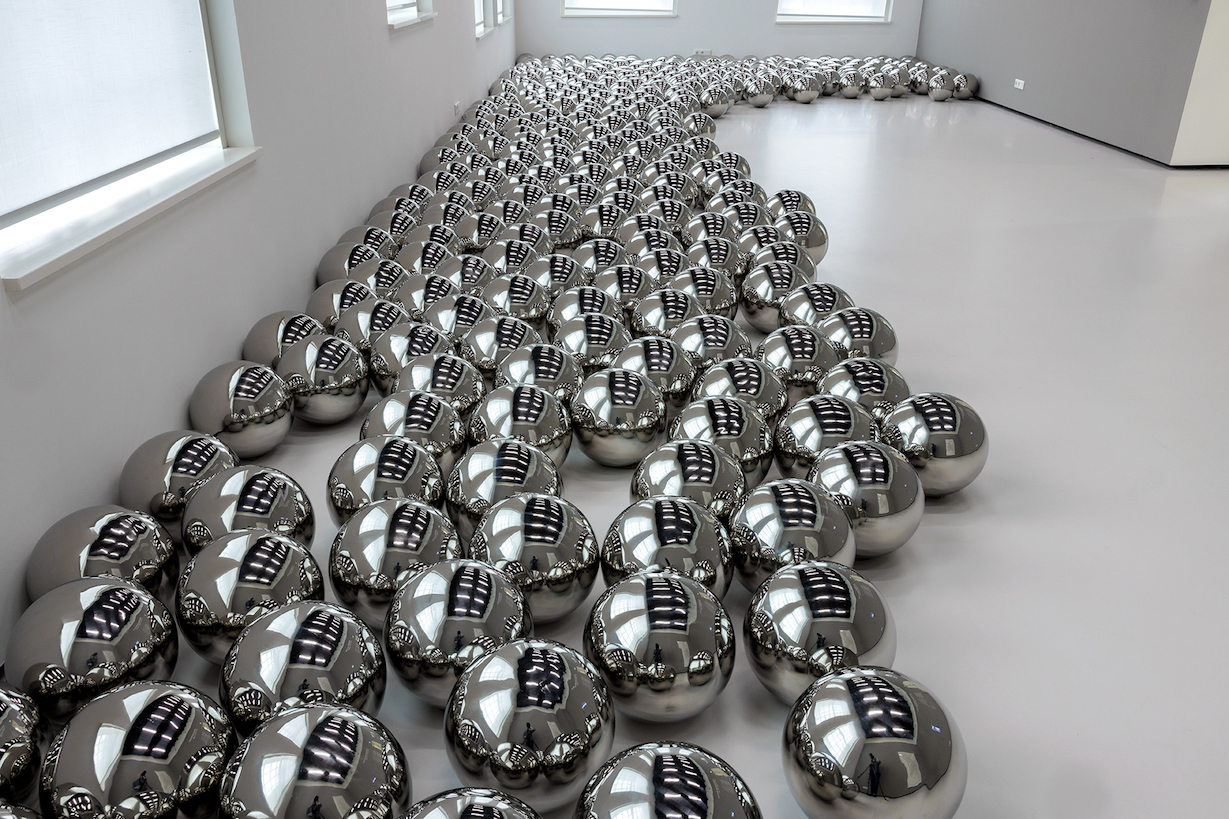

Yayoi Kusama, ‘narcissus garden’ (1966), on view at Yayoi Kusama: The Dutch Years 1965-1970 in Stedelijk Museum Schiedam. Photo: Aad Hoogendoorn

The artist was here: Yayoi Kusama’s Dutch Years at Stedelijk Museum Schiedam

Most exhibition-goers might enjoy the show on Yayoi Kusama at Stedelijk Museum Schiedam because it is a straightforward and well laid-out historical overview with a specific angle on a well-known artist’s trajectory. Manuela Zammit likes the way the show demystified the figure of the artist.

The currently ongoing exhibition Yayoi Kusama: The Dutch Years 1965-1970 at Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, is a show that quietly but confidently states, ‘The artist was here’ — here, in this museum, and yes, here in this very town, and here, in the Netherlands.

I say ‘quietly’ because at this point in time, pretty much everybody knows of Yayoi Kusama in a similar way that everybody knows about Picasso, Monet, or Jeff Koons. Every other person, from art lover to city break tourist in search of cultural capital, has photographed themselves in one of the spectacular Infinity Mirror Rooms that she is most known for. Nowadays, Yayoi Kusama has much more in common with Louis Vuitton and New York City and SFMOMA, than Schiedam. The visual language around her is colourful, hypnotising, explosive and expensive, but in the feather-toned halls of Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, we get to meet an emerging artist quickly learning how to navigate the contemporary art circuits of the time, rather than the mythicised international art world superstar.

Yayoi Kusama, Bunnik, 1970. Photo Harrie Verstappen, courtesy 0-INSTITUTE

We get to know a bit more about Kusama the person rather than the persona — also directly from individuals who spent time with her then — which I consider to be a strength for a project about an artist that has already been widely shown, written about, and storied in a grandiose manner. As the title clearly indicates, the exhibition offers an overview of the five-year period between 1965 and 1970 during which Kusama spent time working and exhibiting in the Netherlands, after she had already moved to the US from her native Japan some years prior in 1957. In this sense, the exhibition functions as a timeline that ends in the spring of 1971, when she left the Netherlands for the last time and returned permanently to Japan. These are called the Dutch years because, as is pointed out, despite living in America, Kusama exhibited much more frequently in the Netherlands than in the US in this time. Her first European exhibition was also held in the Netherlands.

The years between 1965 and 1970 are called the Dutch years because despite living in America, Kusama exhibited much more frequently in the Netherlands than in the US in this time. Her first European exhibition was also held in the Netherlands

The halls are filled with a mix of archival material — among which photographs from private collections, newspaper cuttings, and letters — and Kusama’s earlier works, including over thirty works that have never been exhibited before. A handwritten letter which Kusama wrote to Galerij Orez in 1965 reads, ‘I am looking forward to seeing your gallery and your beautiful country. I am hoping to participate in many of your group shows – but please write me well in advance.’ While the show does not claim that these years were the ones that effectively formed her into the world-famous pioneering artist she is today, it does give a comprehensive overview of how her artistic practice and her network within the art world developed substantially throughout her time in the Netherlands. It also solidifies the Netherlands’ position as a contemporary art hub in that time, and inscribes Schiedam in this segment of (art) history.

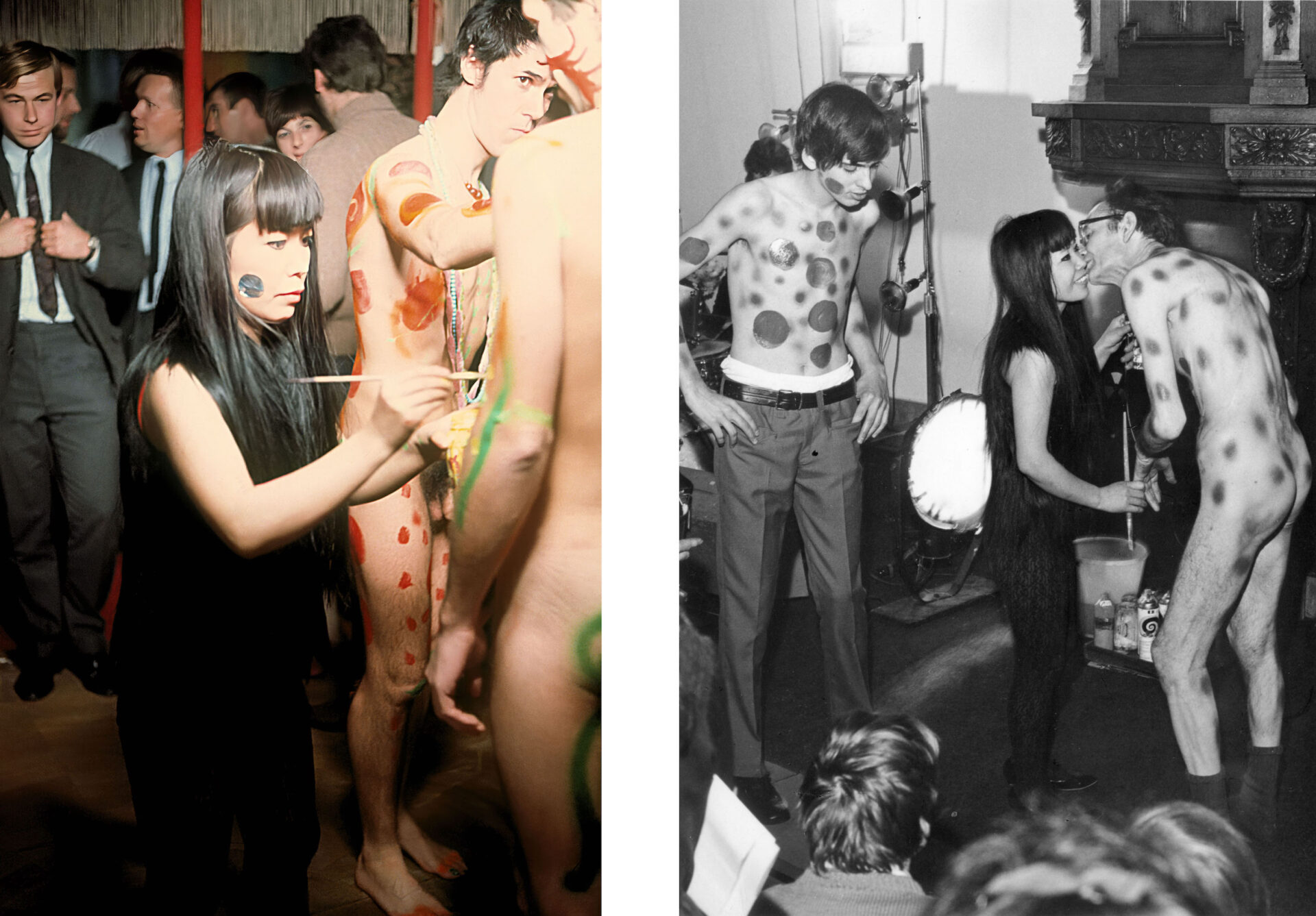

Left: Yayoi Kusama, Birds Club Amsterdam, 1967. Photo Harrie Verstappen, courtesy 0-INSTITUTE. Right: Yayoi Kusama, Naked Body Festival, Stedelijk Museum Schiedam, November 1967. Photo Ton den Haan, collection 0-INSTITUTE

For instance, as the visitor moves through the show, the progression from mostly two-dimensional to increasingly sculptural and spatial works is clearly perceivable. The repeating dot patterns that Kusama is most famous for initially appear as a number of colourful minimalist paintings. Then they do not only spill out into the exhibition space and become the hundreds of mirrored spheres of narcissus garden (1966)—undoubtedly one of the exhibition’s most eye-catching and photographable works—but in a set of photographs taken in 1965 by photographer Harrie Verstappen, we also see how Kusama took to the streets and started painting and pasting the dots on the ground, on cars, and even on herself. In 1967, during the Naked Body Festival held at the Novum jazz club in Delft, Kusama painted the dots on the bodies of her fellow artists Eddie Determeyer, Jan Schoonhoven, Gust Romijn, and Jakob Zekveld. It was a happening that caused much furore and outrage at the time, especially in the media, and the instance in the exhibition that best contextualises Kusama’s Dutch years within the Provo counter-culture movement and the youth culture of the rebellious 1960s.

In 1967 Kusama painted the dots on the bodies of her fellow artists Eddie Determeyer, Jan Schoonhoven, Gust Romijn, and Jakob Zekveld. It was a happening that caused much furore and outrage at the time

Yayoi Kusama, 'narcissus garden' (1966), on view at Yayoi Kusama: The Dutch Years 1965-1970 in Stedelijk Museum Schiedam. Photo: Aad Hoogendoorn

Through this displacement of dots that almost resembles an (artistic) infestation, it becomes clear how Kusama’s artistic practice is a matter of externalising a tumultuous internal world characterised, as we are told, by delusions, visions, and her obsessions with food, flowers, and phalluses. The artist expressed her fears by giving them colours, shapes, a body even, and turning them into art as a coping mechanism. The exhibition texts clarify this, yet luckily do not fall into the trap of romanticising the artist’s psychological condition, or setting it up as a pre-requisite of her artistic talent. Rather, the show also sheds light on how Kusama’s experimentation, for instance with new materials, was also a result of her art world encounters.

Contemporary artists of Kusama’s calibre, and the later Kusama herself, are (too) often elevated to the status of pioneer or visionary, as if their remarkable artistic creations simply occurred to them out of nowhere, rather than being brilliant interventions molded by numerous conversations, collaborations, (failed) experiments, and the artist’s lived experience in their wider social and political context. Again, it is not the case here. The artworks, archival objects, and the accompanying text do work together to trace the artist’s connection to other art world figures, and to give some idea of familiar professional struggles for artists: Kusama’s dissatisfaction with her Dutch gallery’s commercial interests, the way she was exoticised by the Western art scene, and having to find a way to take control of her own public image.

Yayoi Kusama, Schelpkade, close to Internationale Galerij Orez, The Hague, 1967. Photo Harrie Verstappen, courtesy 0-INSTITUTE

Between then and now, Kusama’s internal world has become a room that the viewer can enter, and temporarily happily lose themselves in. Nowadays, regardless of whether one likes her art or not, the legitimacy of her work as art, and its place within a certain strand of Western art history is mostly undisputed. Yet, that was not always the case, as we see in this show. As I left the museum behind, I wondered how many of those appreciating Kusama’s earlier work with the perspective afforded by hindsight, would be skeptical to call contemporary art being made now, art. Most exhibition-goers might enjoy this exhibition because it is a straightforward and well laid-out historical overview with a specific angle on a well-known artist’s trajectory. I liked it mostly because it demystified the figure of the artist.

The exhibition sheds light on how Kusama’s experimentation, for instance with new materials, was also a result of her art world encounters

My parting observation is that not only the contemporary artist has to carve out a place for themselves within the art world, but contemporary art itself has to continually fight for its status as such. It was the case then, and continues to be the case now. The last room of the exhibition, recollecting the night when Kusama painted polka dots on her collaborators’ naked bodies, detailed how the happening was widely regarded as outrageous, scandalous, and as having nothing to do with art in the days after it took place. It turns out, it did. The artist was here.

The exhibition is complemented with a good-looking catalog of the same title, published by nai10

Yayoi Kusama: De Nederlandse Jaren 1965-1970 (Yayoi Kusama: The Dutch Years 1965-1970) is on view at Stedelijk Museum Schiedam until February 25th, 2024

Manuela Zammit

is a writer and researcher from Malta