A truly emancipating exhibition? On ‘Hexed, Vexed and Sexed’ at West, The Hague

The exhibition Hexed, Vexed and Sexed at West features eight female Korean artists in a wide generational range: from Teresa Hak Kyung Cha, born in the fifties, to Eunsae Lee, an artist born in the eighties and who is currently a resident at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. Minsun Kim visits the show and has some critical remarks about the narrative of genuine solidarity and emancipation West engages in.

About a year ago, I visited Simple Acts of Listening at West, an exhibition with work by Korean artists with immigrant experiences, aiming to redefine ‘Listening’ as a socio-political act. The show received a commendable response, prompting a follow-up exhibition that is on view today: Hexed, Vexed, and Sexed. This new show expands the previously explored acts of listening further into feminism, with work by eight Korean female artists. It explores Hex, emphasizing women’s potent yet unconventional power that challenges patriarchy, Vex, breaking boundaries beyond class and race, and Sex, signifying total emancipation through a societal shift in human sexuality. I visit the current exhibition with a curious mind, wondering how it might explore the potential for women’s emancipation while not confining women solely within the label of ‘woman’.

Hexed, Vexed and Sexed is the result of a collaboration between Baruch Gottlieb, regular curator at West, and Ji Yoon Yang, director of Alternative Space LOOP: a non-profit art institution in Seoul. In South Korea’s capital, LOOP has emerged in 1999 as a rare, responsive space offering an alternative perspective toward the conventional white cube spaces in the city. It aims to foster diverse international discourse beyond domestic discussions. With Yang’s leadership, LOOP not only challenges established institutional viewpoints but also amplifies a female perspective within the predominantly patriarchal art scene. Recent initiatives like the ‘Earthsea Study’ program, which invites five female curators working in Seoul, Taipei, San Francisco, and Yogyakarta to discuss their practice and its relation to eco-feminism, stand out for emphasizing solidarity among Asian female practitioners.

In line with LOOP’s ambitions, the exhibition Hexed, Vexed, and Sexed features eight female Korean artists in a wide generational range: from Teresa Hak Kyung Cha, born in the fifties, to Eunsae Lee, an artist born in the eighties and who is currently a resident at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. The small country of Korea is a place where modernization has occurred faster than anywhere else. The various ways in which different generations of women capture these constant changes from their own distinct perspectives is an important aspect of the exhibition.

With Yang’s leadership, LOOP not only challenges established institutional viewpoints but also amplifies a female perspective within the predominantly patriarchal art scene

The spatial arrangement of the current show is different from last year’s. In the previous exhibition, each artwork was displayed in a row in West’s significant corridor, recalling enough of the building’s former use as the US embassy. This current exhibition extends across parts of the 1st floor corridor and the ground floor, leading to the auditorium room. Audiences might easily overlook some of the works due to the exhibition spanning relatively sporadically. It continues from the inner space to the outer garden, where an installation by the artist Ye Eun Min is displayed using items collected while wandering around The Hague.

In the exhibition, there’s an evident exploration beyond one’s own identity across all the artistic practices, seeking new expansions rather than being confined by gender boundaries. Among them lies a work most directly related to the emancipatory power of women, capable of subverting patriarchal society: Chang Jia’s Beautiful Instruments 3: Breaking Wheel.

Chang Jia

With her series Beautiful Instruments, Chang recreates scenes of historical torture into new instruments, based on the artist’s imagination. Upon entering her exhibition space, visitors will be drawn to the singing of women from a video. This video documents a performance, featuring 12 large wheels adorned with flowers and feathers. The wheels, which remind us of a tool for labor, were used as a device of torture or the death penalty in medieval Europe.

Chang Jia, 'Beautiful Instruments 3: Breaking Wheel', part of a series of 12 collages (2023), installed at 'Hexed, Vexed and Sexed: 8 Women Artists from Korea'

In the performance that we see documented in the video, 12 female performers seated on the saddle of the instrument rotate each wheel by moving their legs, causing the feathers to graze by their genitalia. To exert force in spinning the heavy wheel, women 디딜 방아 타령 (Didil Banga Taryeong): one of the many labor songs that workers used to sing while farming in Korea. Each region in Korea has its own labor song, and the source is always unclear because it is passed down from mouth to mouth.

In the video, 12 female performers seated on the saddle of the instrument rotate each wheel by moving their legs, causing the feathers to graze by their genitalia

Chang Jia, 'Beautiful Instruments 3: Breaking Wheel' (2014), installed at 'Hexed, Vexed and Sexed: 8 Women Artists from Korea'

While turning the wheel is strenuous, the more it turns, the more it intensifies the women’s sexual pleasure. Crystalized words adorn the saddles on which performers sit, but audiences cannot read the words inscribed on the saddles, which exceed 2 meters. Additionally, any marks left on their buttocks as they spin the wheel disappear after the performance ends. The eroticism of women enjoying pleasure through feathers on the wheel, rather than the productivity enforced by labor through the wheel, transcends the conventional constellation that labor songs and religious music were supposed to provoke. The 12 engraved words on the saddle are selected by the artist, considering them as crucial elements that revolve around the artist’s perception of the world. Those 12 words are assembled into 12 collages, and currently, four of them are exhibited at West.

Teresa Hak Kyung Cha

Ascending the stairs to the first floor, one encounters six different rooms by three artists in a corridor. Among them is a work by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha: a Korean-American artist whose work is more widely recognized and exhibited overseas than in South Korea. She was born during the Korean War while her family was evacuating from Seoul to Busan. Afterward, Cha and her family emigrated to escape South Korea’s post-war dictatorship and settled in the U.S., this continued immigrant experience deeply affected her practice.

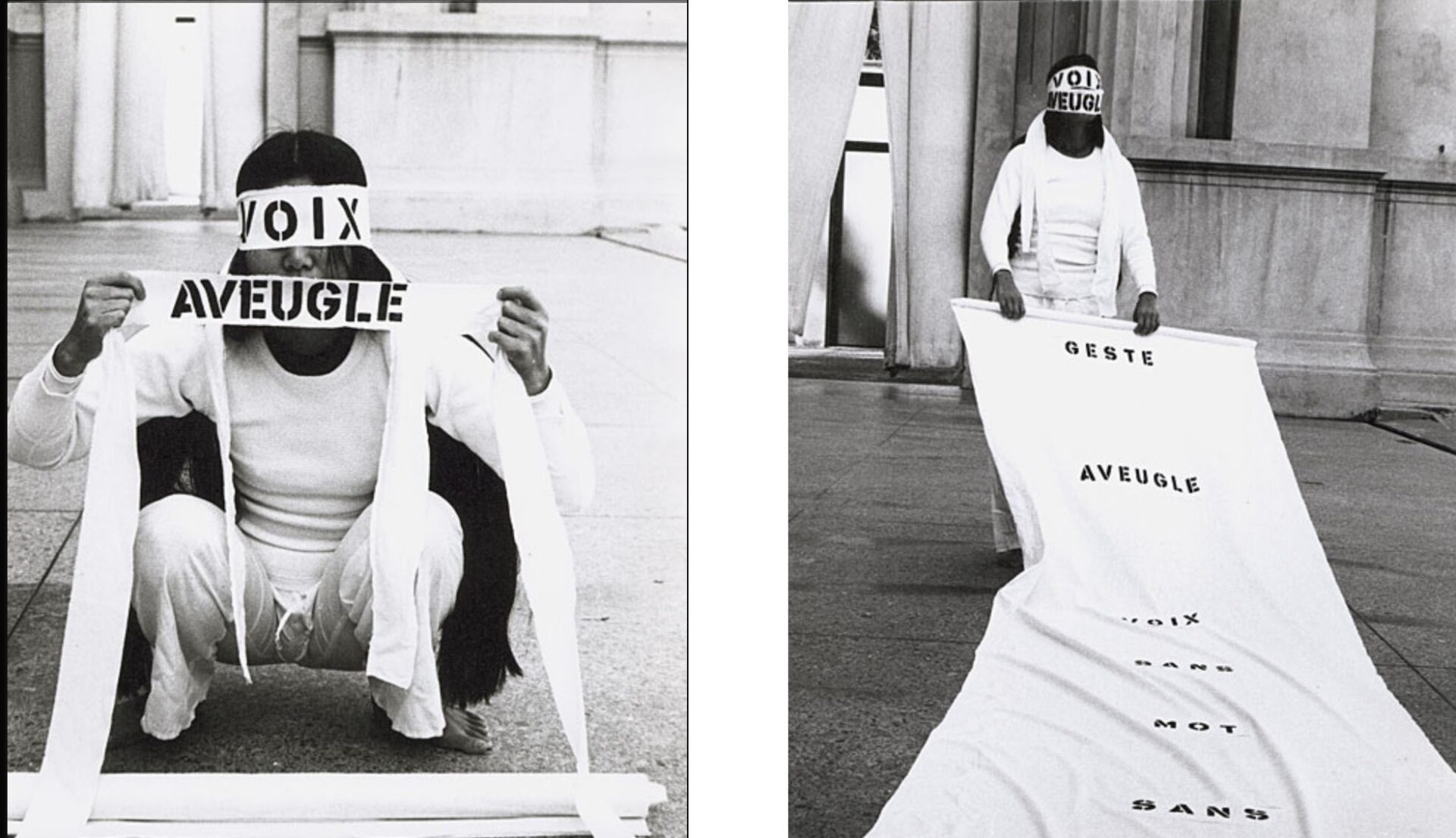

In this show, two of her works are displayed in separate rooms. Upon entering the first room, viewers are faced with AVEUGLE VOIX (Blind Voice): a series of images that serves as documentation of a performance Cha presented in 1975. We see her dressed completely in white, her long, flowing black hair sharply standing out against it. She obscures her eyes and mouth with long white fabric containing the French words ‘Voix (Voice)’ and ‘Aveugle (blind)’ in black letters. Then she continues to unfold a white fabric roll, revealing the words ‘geste/ aveugle / voix / sans / mot / sans / me (gesture/ blind / voice / without / word / without / me)’ and ‘words / fail / me’, with their interpretation changing depending how much of the fabric roll she unfolds and the order in which they are read.

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, 'Aveugle Voix', Performance Image, 1975

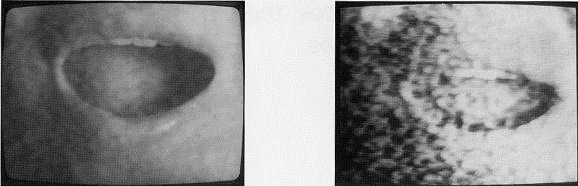

Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, 'Mouth to Mouth' (1975)

Cha’s poetic experimentation with language becomes even more evident in a piece that is on view in the next room called Mouth to Mouth (1975): a single-channel videotape which shows her mouth. It seems as though she is pronouncing Korean vowels, but instead of those sounds, we hear the sound of water and wind. It’s interesting to realise how non-Korean audiences might not even recognize the mouth’s movements as producing a Korean vowel; they may recall the gesture of her mouth through any familiar language they know

Reflection

During the opening Q&A, someone from the audience asks why this exhibition, that wants to promote the freedom of women through work by ‘Korean’ women, is shown abroad, rather than within the country of Korea itself? Gottlieb answers that with the rising popularity of K-culture, the media often portrays Korean women through a limited lens. He says that while the media showcases certain images of Korean women, there’s a need to represent the diverse spectrum of Korean females beyond these narrow depictions.

Curators Baruch Gottlieb and Ji Yoon Yang and artists Chang Jia and Eunsae Lee during the artist talk at West, on the occassion of the exhibition 'Hexed, Vexed and Sexed: 8 Women Artists from Korea'

On the one hand, you could say that this exhibition succeeds in presenting that variety. On the other hand, however, the show still holds onto the artists’ overarching identity as ‘Korean women’. This is a label imposed by external perspectives; we wouldn’t put the name tags on ourselves. Marginalized beings in society, such as women and people of color, are easily at risk of recognizing their existence through the gaze of others rather than their own subjectivity. And those external gazes, when deeply internalized, become a cruel tool to judge those who fall under the same category as them, fostering misogyny within women and intra-racial discrimination by the embedded external perspective.

Why is this exhibition, that wants to promote the freedom of women through work by ‘Korean’ women, shown abroad, rather than within the country of Korea itself?

However, paradoxically, we also find a necessity in these categories, as they offer visibility and a platform for recognition. This duality prompts us to adopt these labels for acknowledgment while simultaneously challenging and transcending their limitations.

The collaborative exhibition between West and Alternative Space Loop showcases diversity within the context of European art scene. However, I wonder how we can engage in a narrative of genuine solidarity and emancipation, not confined to a restricted ‘we’, but inclusive of an expanded and multi-dimensional ‘we’, with and against the label of K and women.

Hexed, Vexed and Sexed is on view until January 14 at West, The Hague

Minsun Kim

is an artistic research-based practitioner