‘May Contain Traces of Preemptive Obedience’ – 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art

The Berlin Biennale takes place at a time where the intersections of art, politics and censorship are getting more and more entangled in Germany. Ana Teixeira Pinto visits the 13th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art titled passing the fugitive on, where she wonders if encoded political messages are not also ways of running away from the real issues at hand.

The sentence ‘May Contain Traces of Preemptive Obedience’ is printed onto a dishcloth, hung on flower-shaped wall hooks. There are many dishcloths surrounding the viewer, and all of them display variations of that same sentence ‘May Contain Traces of…’. The cloths frame the centre piece of Helena Uambembe’s intallation, a video titled How to Make a Mud Cake, shot in the style of baking tutorials, howbeit with different ingredients. We are not talking about sugar or flour. We are talking about pain and personal trauma, reworked into an (edible) commodity. Uambembe is scathing about trauma hustling, but it’s not the supply side she has on her sights. It’s the appetite for sentimentalized tragedy, eager to give universal meaning to the trauma it inflicts on others without taking responsibility for it. ‘May contains traces of racial killings’. Wipe your hands with it.

But this proposition also poses a question: Whose pain can be commodified? Whose pain can be given universal meaning? Whose pain must remain unacknowledged in order to not compromise the victory of humanism?

The 13th Berlin Biennale, curated by Zasha Colah, explores themes of fugitivity, subversion, and art’s endurance under repressive regimes. Titled passing the fugitive on, one could read the exhibition as a ‘how to’ manual meant for a country undergoing a process of social transmogrification. ‘Foxing’––a noun turned into a verb– is how you communicate under illiberal regimes, hence the recipe: the artwork carries a message spoken in code. The sheer presence of so many encoded messages provides a diagnose for the erosion of democracy and constitutional guarantees.

It’s an elegant proposition, and it’s elegantly articulated. But its theoretical elegance sometimes outpaces its political coherence. Just a cursive look at the catalogue shows that among the contributors one finds Kate Sutton, who resigned as Artforum editor in solidarity with David Velasco, ousted for publishing an open letter protesting the humanitarian crisis that besieged Palestinians are facing in the Gaza Strip. And Kito Nedo, a journalist who has been accused of waging a campaign to defund Jewish artist Frieda Toranzo Jaeger, by sending screenshots of pro-Palestine Instagram posts the artist had liked to several institutions including her gallery. The Biennial denies these accusations but Jaeger claims his emails led her to lose an exhibition and the stipend associated with it. At any rate, none of this happens in a vacuum, the high percentage of Jewish voices deplatformed in Germany ––25% of all documented incidents–– suggest that “kauft nicht bei Juden!” has been repackaged as Zivilcourage, the Salonfähig version of xenophobic nativism. Strange bedfellows may be an apt, if laconic, summary.

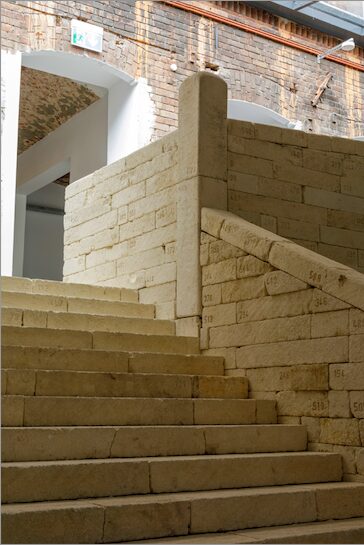

Eloquence aside, the curatorial proposition is also an ineffective one. By celebrating illegibility and artistic survival under oppressive systems, inarticulation can pose as encryption. To give just two examples one could point to Margherita Moscardini’s The Stairway whose design reflects the architecture of the Tomb of the Virgin Mary in East Jerusalem. And Armin Linke’s Negotiation Tables, a photographic installation carving up Anton von Werner’s 1881 painting The Congress of Berlin, the congress which carved up the Balkan region –a stage for great power competition– reorganizing the borders of southeastern European states, and recognizing the Ottoman era status of Jerusalem as multi-religious site. Both represent circuitous ways of alluding, obliquely, to the elephant in the fox den. Some may say this is ingenious. As one reviewer put it ‘once one embraces the absences that propel the elisions, dissent, and black humor that structure the exhibition’ the (missing) references to Palestine ‘begin to appear everywhere’. Alternatively, one could say: What is repressed is always destined to return, even if only in the form of a compromise. Or simply: Let’s have our mud cake and eat it.

There is also a conservative undercurrent to the idea of evading legibility: if the selling-point is to move beyond literal representation are we not tool-boxing postmodernism/ advocating for a world where deciphering code successfully is called art criticism? By contrast Simon Wachsmuth’s From Heaven High—a reference to Prussian Arcangel by John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter—takes a rather more productive shortcut, addressing the impact of Staatsräson on the German polity by staging a dialogue between a judge and a pig-faced military officer, that does not shy away from historical analogy.

‘If you want to tell people the truth, make them laugh’, says the aphorism, ‘otherwise they will kill you.’ The Biennale embraces this motto to foreground dark humour and restorative laughter as tools of resilience. But if humour can point to the attachments that help reproduce what is most damaging in the world, showing they are at the same time what holds the world together as a coherent representation—as with Gernot Wieland, Fredj Moussa or Gabriel Alarcón—it can also cultivate an absence of empathy, and the same language of vulgarity the far-right made popular in recent years.

But let’s return to the foxes, pigs, elephants: ‘They are all beasts of burden, in a sense, made to carry some portion of our thoughts’, Henry David Thoreau once quipped. And I cannot help but insert a side note: the Berlin Biennale, the São Paulo Biennial, the Istanbul Biennale, all burden the animal with the task of conceptual mediation—apparently the human is a too controversial site for it.

Unlike foxes, sly and cunning, elephants are sheer mass and weight. They are difficult to miss. The elephant in this biennial is the not so much the war on Gaza and the unfolding genocide against Palestinian civilians. It’s what it reveals about Germany and its ongoing embargo on facts. The country drew a partial lesson from history: not never again genocide but never again antisemitism. For the punditry, calling for a ceasefire is equivalent to calling for the erasure of Jewish people, expressing concern for civilian casualties implies support for terrorism, and having a sense of compassion is a symptom of moral bankruptcy. In short, protesting genocide is recodified as antisemitism, and empathy is considered a hate crime.

In an interview recorded in the runup to the opening, the curator denied there was censorship in the country. ‘Not legally.’ This is debatable. With the tacit connivance of the state, violence is indeed externalised to civil society and repression is carried out by extra-legal means—the above-mentioned Biennale contributor moonlighting as vigilante being a case in point. But although Germany does not have a system of prior restraint, laws exist to address speech that is considered illegal, and to enforce removal of content. Here we usually think of swastikas and holocaust denial, but many other forms of political expression are illegal in Germany, for instance symbols of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), or symbols of banned communist organizations like the SED and KPD. On 11 November 2023, the phrase ‘from the river to the sea’ was banned in Bavaria and the prosecutor’s office warned that henceforth its use, regardless of intent, will be treated as the use of a symbol of a terrorist organization. ‘Insult’ (Beleidigung) is also a crime under German law, and Stefan Niehoff, a 64-year-old retiree, saw his home raided by police for posting a meme juxtaposing Green Party candidate Robert Habeck and the logo of the German haircare brand ‘Schwarzkopf Professional’, altered to read ‘Schwachkopf Professional’—which translates as “professional dimwit”. Next to pre-emptive obedience, efforts were made to formalise censorship. The documenta gGmbH, to give but one example, adopted the IHRA’s definition in its new Code of Conduct, admitting that it can only guarantee ‘freedom of artistic expression within the scope of the applicable legislation in Germany’. Should documenta judge that forms of artistic expression are in conflict with the principles of conduct expressed in this Code of Conduct, it reserves the right to intervene ‘in the immediate visual context of the works of art exhibited’. Political pressure also forced the cancelation of a public lecture by Francesca Albanese, UN Special Rapporteur on the Occupied Palestinian territories, and Diaspora Alliance compiled a list 84 cases of deplatforming or event cancellations related to expressions of solidarity with the Palestinian plight.

You may say the curator simply misspoke, and it’s an overkill to devote so many words to refute what was never intended as a denial that censorship exists. This Biennale seeks, she tells us, the restoration of a voice that speaks in its own terms, ‘stifled in various art contexts, globally.’ But this restoration is distributed unevenly. And while demanding identical treatment for all oppressed groups can become a tool to avoid engagement—especially when artists involved in the Civil Disobedience Movement in Myanmar are exhibiting—when we avoid Palestine because it’s ‘too controversial,’ we reward the very power structures that rank suffering and refuse to acknowledge Palestinian pain because it unsettles the post-war consensus and Germany’s position within it. Faced with the judicial harassment, the deplatforming, the deportations, evasions, elisions, omissions and blunt police force in Germany, the Biennale apparently asks us to ‘turn fugitive’, to ‘run with it’, to ‘keep it in hiding until its transmissible, sayable.’ Yes, we understand it’s a coded message, meant for those experiencing the brunt of state violence in Germany and yes, we all know ‘one day, everyone will have always been against this’. But that day will never come unless we strive to meet it.

The 13th Berlin Biennale is on show until the 14th of September

Ana Teixeira Pinto