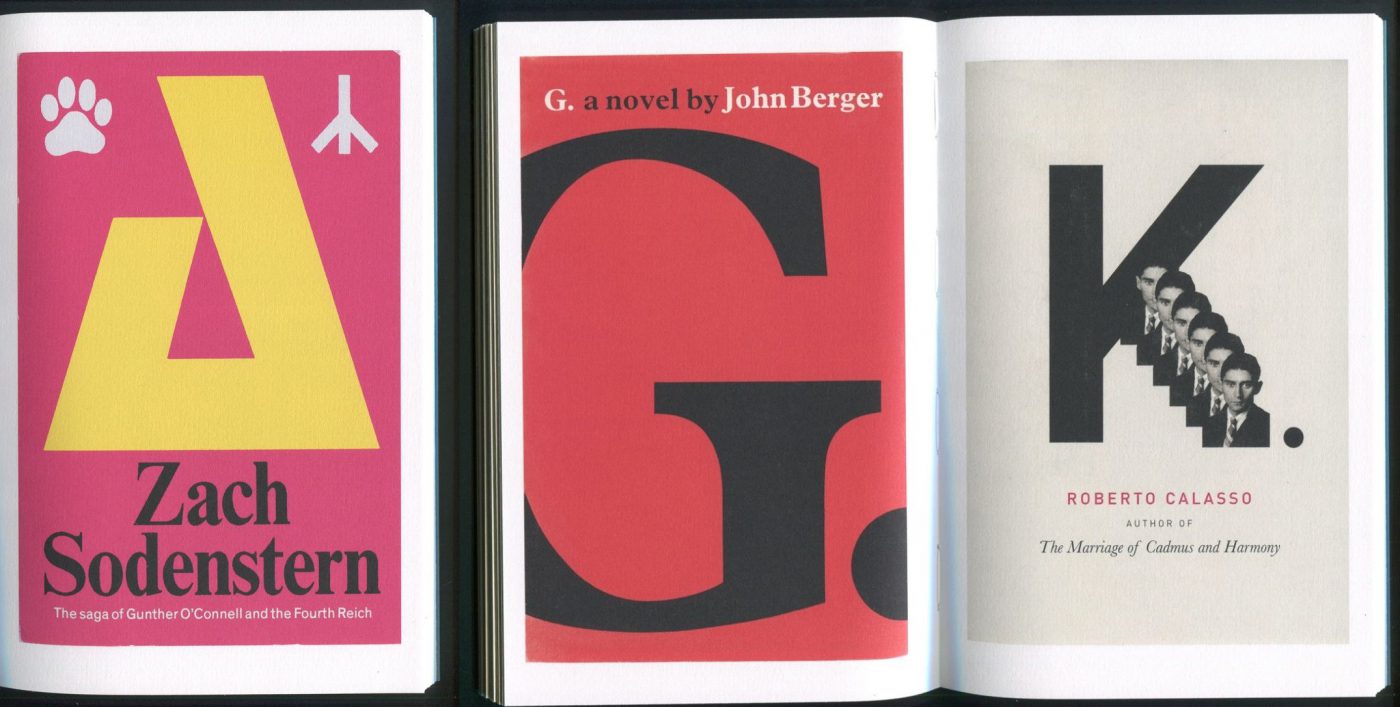

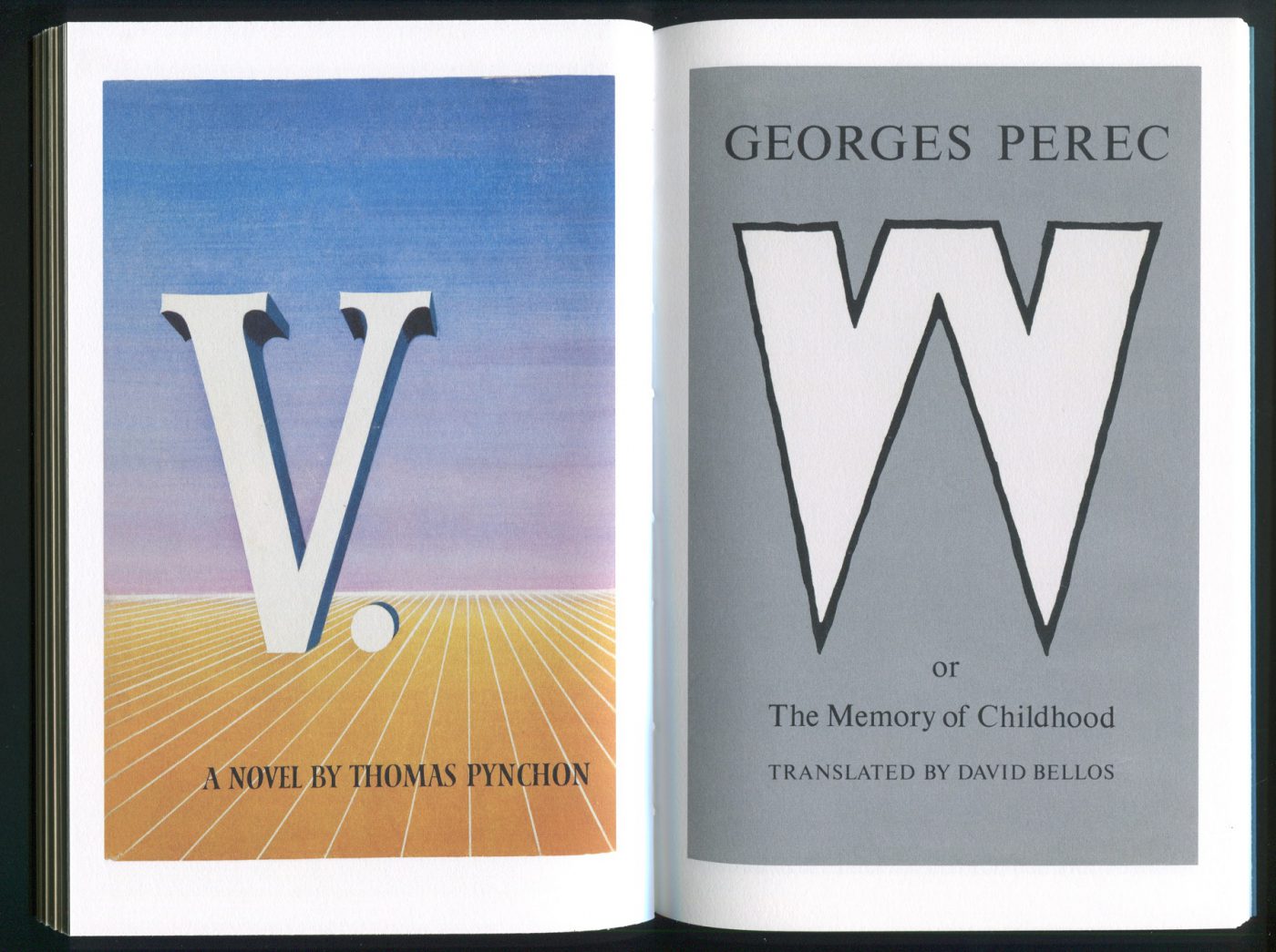

Louis Lüthi, pages from the book

Only the ‘L’ is missing – Louis Lüthi’s collection of alphabet books

Some of the books are well-known – Andy Warhol’s a: A Novel, Georges Perec’s W, or the Memory of Childhood, Thomas Pynchon’s V. Louis Lüthi on his book A Die with Twenty-Six Faces (see also Metropolis M Nr 1-2019 Circulation), a metafictional essay and a literary quest through his collection of alphabet books, or books with letters for titles.

Mixing fiction, typography, literary analysis and essayistic elements Louis Lüthi guides us through his collection of (real and imaginary) alphabet books. Alphabet books are books with letters for titles. Only one letter is missing from L.’s collection: the letter ‘L’, but Lüthi, or should I say L.?, has found a pretty original solution to that problem: the present book carries the letter L on its cover.

Where does your interest in alphabet books come from?

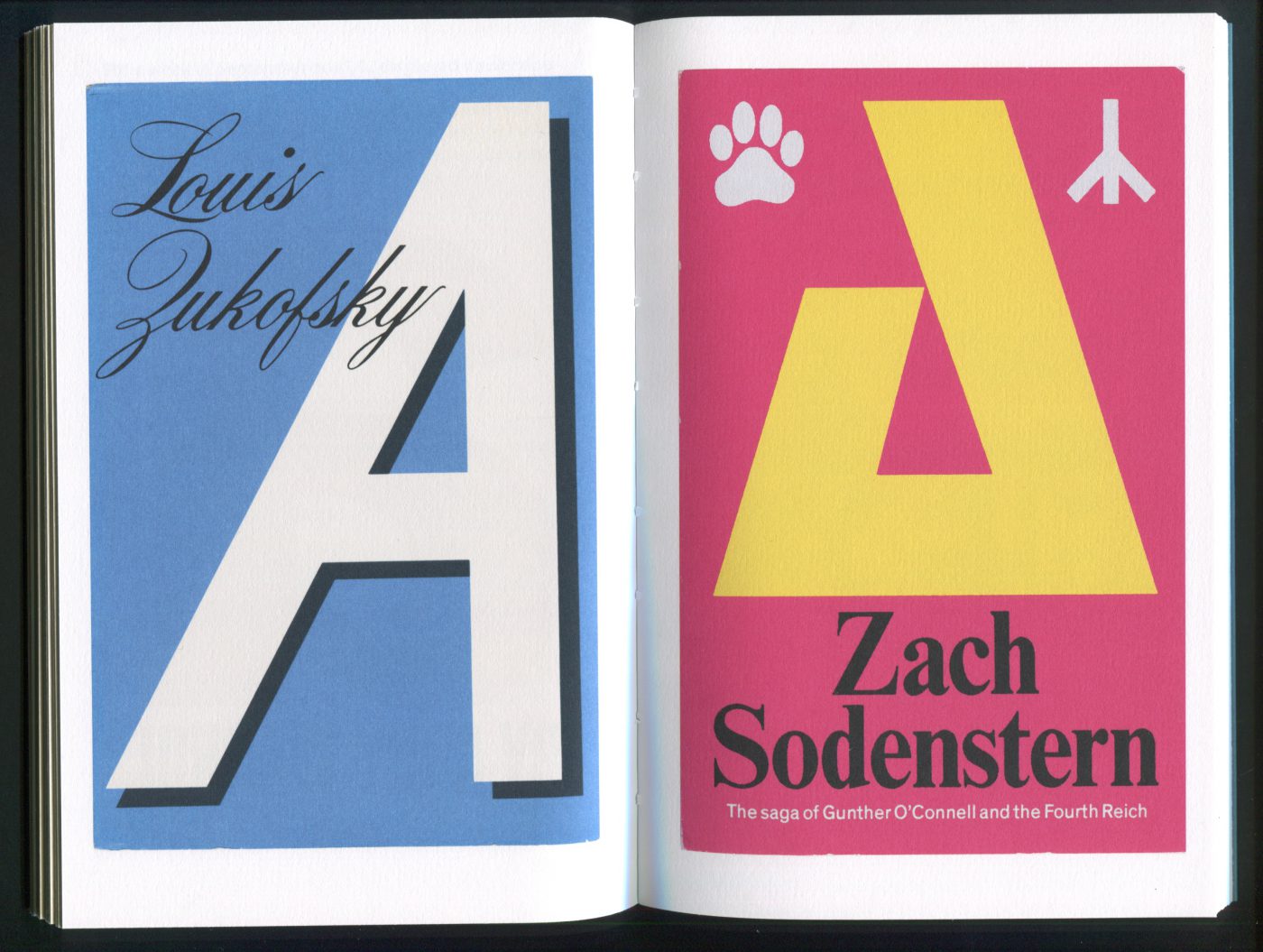

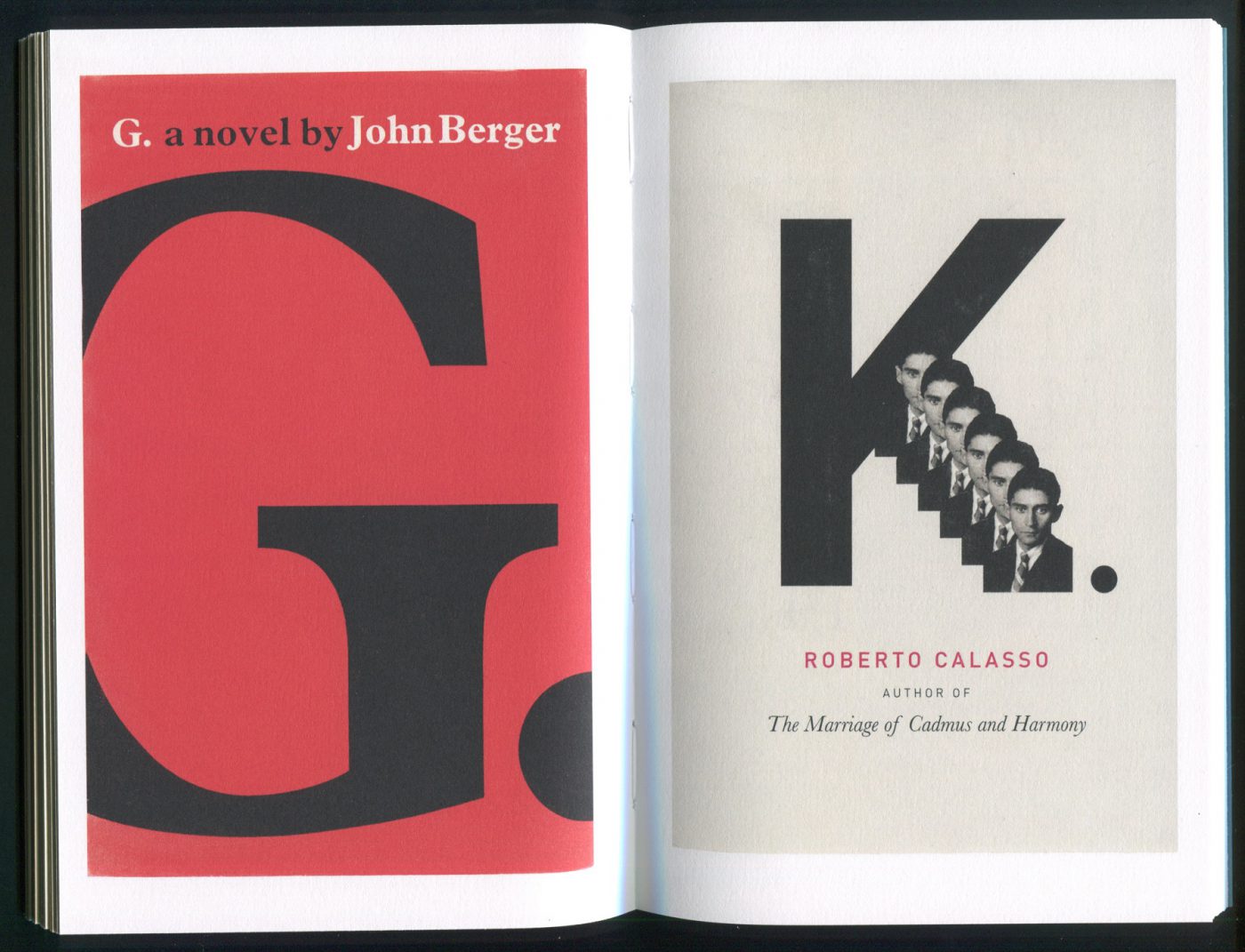

I guess from a general interest in the relation between writing and typography. I started collecting books with letters for titles years ago, simply out of curiosity, and more or less haphazardly. Later, I realized that this collection could form the basis for an essay about typography and literature. I found that limiting myself to these thirty-odd books (I don’t write about all of them) was a constraint that allowed me to explore the topic freely. Some of the books are well-known – Andy Warhol’s a: A Novel, Georges Perec’s W, or the Memory of Childhood, Thomas Pynchon’s V. – but others are pretty obscure, and these were fun to track down and challenging to write about. Also, searching for titles from A to Z became a structural device.

I found the way you make use of letters in the book very interesting. They don’t just function as sounds or vowels but also as symbols, forms and materials. Reading the book, I was thinking that this way of approaching letters might be where your interest for literature and your work as typographer intersect.

I’m not really interested in concrete poetry, and I purposely avoided some of the more tired tropes when it comes to language and the visual arts – synesthesia, for instance, or seeing writing and letters as landscapes. It’s worth pointing out that I write mostly about novels, and a few essays and long poems. At the beginning of the book I reference an essay by Guy Davenport in which he mentions what he calls the “Kells effect.” I was really intrigued by this term. Davenport uses it in relation to James Joyce’s Ulysses. Basically, he argues that prominent letterforms can serve a larger thematic and structural purpose in a work. The term itself refers to the Book of Kells, the Irish illuminated manuscript from the ninth century that’s decorated with ornate lettering – lettering that often adds a layer of significance to, if not commentary on, the main text, the Gospels. So I was intrigued by Davenport’s suggestion that a similar logic might underpin works of contemporary literature, even if they are mass-produced novels that contain few or no such decorative elements or illustrations. You could say that my book is a survey of the Kells effect at the end of the Gutenberg era.

You already mentioned the essayistic aspect of your book; style-wise it hovers between iction, literary analysis and essay. Why did you decide to write in such a hybrid format?

I wanted not only to explicate a selection of writings, but to engage with them on a conceptual and material level. It started as an essay, but the narrator gradually became more prominent, and I started to incorporate elements of fiction: the narrator – that is, the figure of the reader – became a character.

‘Many of the illustrations are reproductions of covers, title pages, and flap texts – examples of what Gerard Génette calls the paratext: the material that surrounds the text and frames it in a certain way. In my book, this material becomes part of the text’

Spread from Louis Lüthi - A Die with Twenty-Six Faces

What, if any, is for you the difference between reproducing parts of other books and writing?

Ultimately I guess I consider it all writing. My books combine reading and writing, text and image, quotation and appropriation. Seeing as A Die with Twenty-Six Faces is a book about typography, I felt it was important to incorporate images of words in various media: printed words, handwritten words, digitized words, engraved words, filmed words.

You make a pretty unconventional move for a collector as you produce the very work, a book with the letter ‘L’ on the cover, that would complete your collection of alphabet books. There is humour in there, is there anything else you want to say with it?

It just so happens that L is the only letter missing from my collection. So I called the main character L.: the figure of the reader completes the book, as it were. But although ‘L.’ is on the cover, the title is A Die with Twenty-Six Faces. The cover gestures towards a completion that – farcically – falls just short. L. is obviously an exaggerated version of me – there’s something foolish about the book’s premise, and somehow this foolishness made it possible for me to write.

What does the subjective or fictional do to the idea of collecting?

Of course, the book is a metafictional work in the sense that it’s a book about books, but yes, I’m less interested in an ontology of writing than in how texts are produced, disseminated, and archived. Incorporating elements of fiction allows me to situate these processes in a lived experience – at least I hope the book conveys a sense of lived experience. It also opens up a space for gaps, exceptions, doubts – things that aren’t normally allowed in an archive (or in literary analysis, for that matter). To give an obvious example, the collection is rearranged in multiple ways. Now that I think about it, the book’s hybrid form is also a vital contrast to the encyclopedic or totalizing impulse behind collections, which can be oppressive.

'L. is obviously an exaggerated version of me – there’s something foolish about the book’s premise, and somehow this foolishness made it possible for me to write'

Could you tell me more about the importance of the missing link in relation to collecting?

Craig Dworkin calls this the “phantom shelf”: there’s always another book or author or category that could be added, or a book or author or category that’s been excluded. Of course, this is the unresolvable tension between accumulation and classification. And it’s a truism that the most interesting books and authors resist classification, or even upend our systems of classification.

I was intrigued by the idea of presenting a collection of books within the format of a book. I know you have been making books before so it was probably a natural choice, but there seems to be more to it, as your alphabet book collection will now, as A Die with Twenty-Six Faces, circulate within other libraries and personal collections.

L.’s collection of alphabet books is not grouped together on one shelf but scattered throughout his library. It’s hidden within a larger collection: a dispersed thing, not a monolithic thing. A Die with Twenty-Six Faces is a follow-up of sorts to an earlier book of mine, On the Self-Reflexive Page, which presents a typology of pages from novels that make use of non-verbal devices. Collecting pages from books is a paradoxical idea: how can you collect individual pages? (For one thing, you can’t separate a recto from the verso.) You can only collect reproductions of pages in a new book. A Die with Twenty-Six Faces is about a collection of books, not pages, but I’m very selective of what I take from these books: a quotation here, an image of a page or cover there. In the end, this collage of quotations and images is held together by the main character, L.

It is as if you highlight that every collection consists of multiple collections and that a book also contains various collections.

Exactly, and hopefully this creates a sense of inexhaustible dialogue. It’s also why many of the illustrations are reproductions of covers, title pages, and flap texts – examples of what Gerard Génette calls the paratext: the material that surrounds the text and frames it in a certain way. In my book, this material becomes part of the text.

You once contributed to a book series called The Social Life of the Book. And with Arjun Appadurai concept of the “social life of things” in mind, the social life of book would actually be a very apt description of what happens in A Die with Twenty-Six Faces.

I’m happy you made that connection and I agree. A Die with Twenty-Six Faces takes up many of the themes in “Infant A,” the short piece of fiction I wrote for The Social Life of the Book. In “Infant A,” the narrator goes for an imaginary walk with Ulises Carrión, the Mexican bookmaker who in the 1970s ran Other Books and So, an artist’s bookshop in Amsterdam. And, to go full circle, their conversation revolves around Zukofsky’s “A” and Warhol’s a: A Novel. Like Carrión, I want not only to write texts, but to make books.

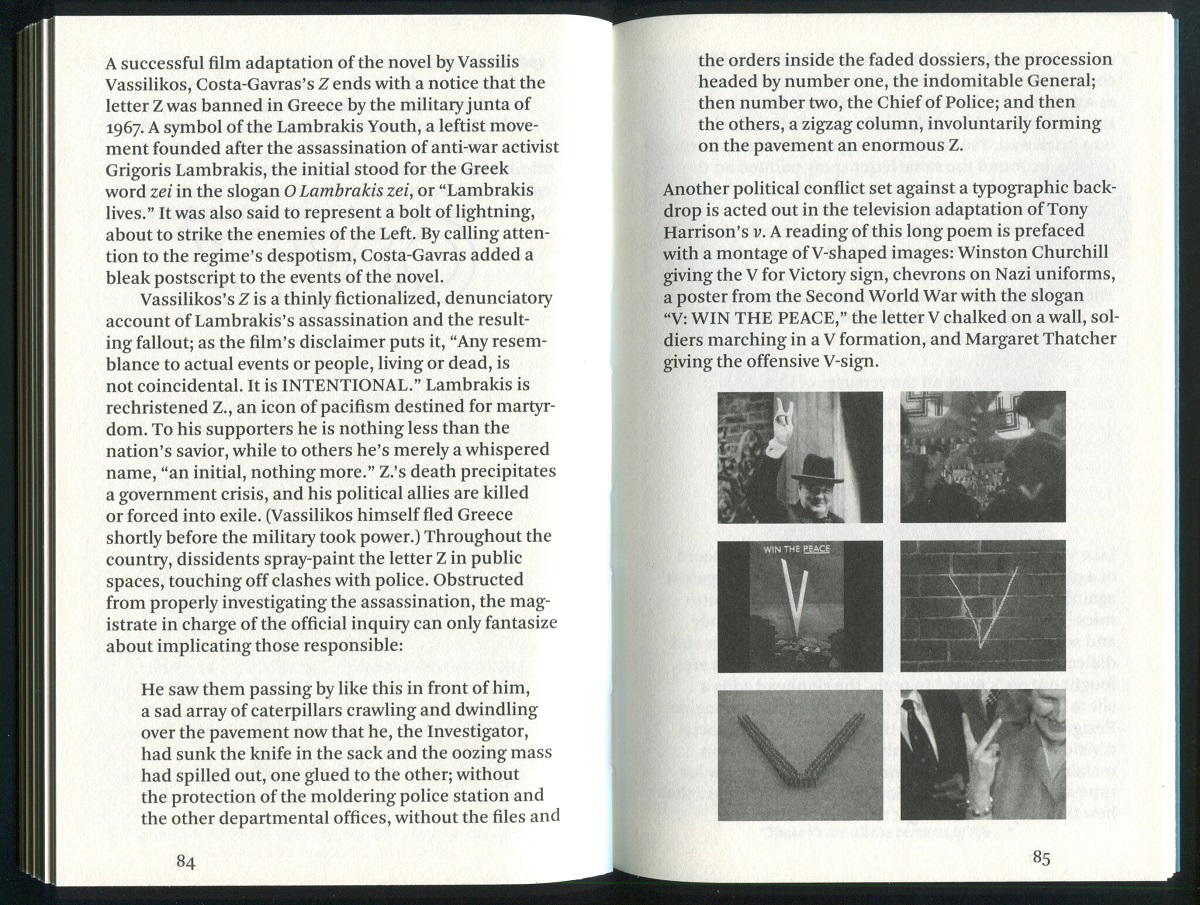

Spread from Louis Lüthi - A Die with Twenty-Six Faces

Spread from Louis Lüthi - A Die with Twenty-Six Faces

Spread from Louis Lüthi - A Die with Twenty-Six Faces

HEB JIJ HEM AL IN HUIS? IN Metropolis M Nr 1-2019 Circulation IS LOUIS LÜTHI’S KUNSTENAARSBRIJDRAGE TE BEWONDEREN EN LEES JE MEER OVER VERZAMELEN EN TYPOGRAPHIE. ALS JE NU EEN JAARABONNEMENT AFSLUIT, STUREN WE JE HET NIEUWSTE NUMMER GRATIS OP. MAIL JE NAAM EN ADRES NAAR [email protected]

Louis Lüthi – A Die with Twenty-Six Pages, 2019. ISBN: 9789492811394, published by Roma Publications in collaboration with Gerrit Rietveld Academie Lectoraat Art & Public Space

Zoë Dankert

schrijft