A Continuous Dialogue

As an alumna of the Piet Zwart Institute (2004-2006) and the Rijksakademie (2010-2011), I believe there is a considerable difference between an MA programme and a postgraduate or residency programme. While trying to draft parallels and differences between these two programmes, let’s first of all keep in mind that the Rijksakademie is not an educational, degree-based programme and is committed to facilitating and hosting more than twice as many participating artists as the Piet Zwart Institute does. These facts certainly dictate how these institutes are formed and managed. Both are centred on the individual trajectories of the participants, but their relation to the day-to-day practices of the artists differs quite a bit.

While one certainly shouldn’t underestimate the possibility of growth through self-study in the comfort of a financed residency programme in a well-situated European city, and within an institutional framework offering an extensive library, archives, artist’s studios, et cetera, the focus of the Rijksakademie and its attitude towards developing and sharing knowledge is not formalized and structured. With occasional and dissociated presentations and lectures, the stage was mostly given to advisors while I was there, allowing residents to get to know their advisor’s practice and interests in more depth, instead of presenting a coherent programme, as is the case with a number of master studies, including the Piet Zwart Institute. The focus was on the artist’s studio practice and on developing primarily tactile skills, through for instance wood, metal or ceramic workshops with the assistance of the workshop leaders. Artists also would get a facilitator, a person who would, when needed, try to help arrange the practicalities around the artist’s project. One year of activity came to a climax in the form of Open Studios, during which professionals and the general public had a chance to see the artist’s work.

At the Piet Zwart Institute however, the discursive practice converged with the studio practice and therefore intensive reading, discussions, book projects, seminars, and symposiums were highly stimulated. It was also possible to gain practical knowledge and be helped by the staff of the Willem de Kooning Academy. Unlike the Rijksakademie, the Piet Zwart Institute is not a paid programme; however, each student would be given a budget for their final project as well as free excursions (we visited the Berlin Biennale, for instance). Students would conclude their two-year period of research and practice with a final project, consisting of an artwork, exhibition and a reflective body of thought developed in the format of master thesis supported by a writing tutor and assessed by an internal and external committee (from Plymouth University). The relation of the students to the visiting artists and theorists also differed. At the Piet Zwart Institute we could have a continuous dialogue with our tutors, since the students themselves would sign up for the studio visits, while at the Rijksakademie the process for the meetings with the advisors was not as transparent.

At the Piet Zwart Institute, students could have an on-going dialogue with a number of tutors. This was really fantastic because one could go deeper into conversations about the work every time, and still obtain a fresh and objective view from the guest tutors. The tutors were practitioners of different disciplines with different sensibilities, and I find this important because as such they were helping us orientate and position our interests. Through the tutors we were always in dialogue with other ways of making and thinking about art, while there was also constant and generous support for the specific interests of each student. I have the feeling that this facilitated the possibility of not only developing but also criticizing one’s own ideas and preferences, thus giving tools to situate one’s practice in the larger context of contemporary art. My tutors were accomplices and sounding boards, loving, critical and committed. In addition to the most inspiring and wonderful conversations, I remember that I would often have a productive after-talk headache with millions of new questions and references to examine and read.

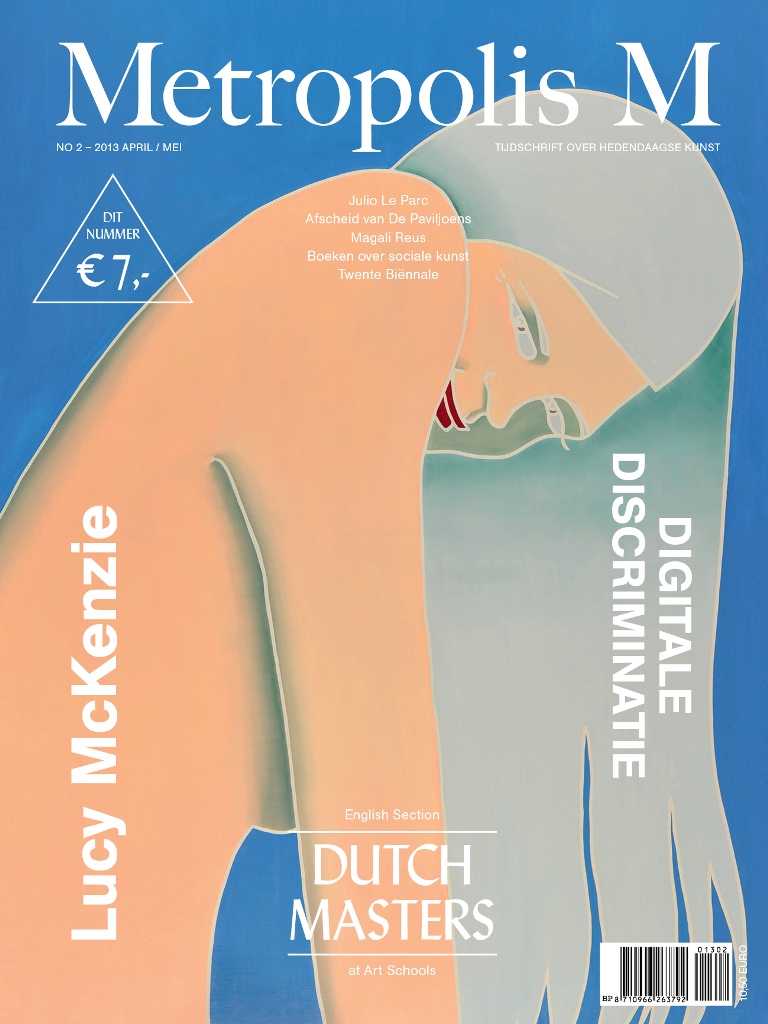

Both the Piet Zwart Institute and the Rijksakademie are highly international, which I consider one of the most valuable assets of the Dutch art climate and education in general. But the current tendency in this regard is not the most promising one. I must note that the tuition fee for an MA programme in the last few years (the figures given here are from the Piet Zwart Institute website, but there are even more drastic examples) is influencing the type of students we are receiving, as the annual tuition fee for EU/EEA countries is 1771 euros, while for non-EU/EEA countries it is 8600 euros. I find this deeply disturbing, because the choice of art students becomes subject to the preferences and discriminations of the economic community of EU/EEA countries and accessible only to the economic elite of non-EU/EEA countries. Is this the kind of criteria we should be led by?

Katarina Zdjelar is a visual artist living in Rotterdam, a former student of the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, a former resident of the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam and currently a tutor in the MAR programme in The Hague.