Ovartaci, Untitled (Den kinesiske formel, The Chinese Formula), undated, private collection: Photo: Ole Hein II

Unwanted bodies – resistance and refusal – Becoming Ovartaci and Danish Cobra 75

Outsider, intellectual, poet, traveler, psychiatric patient and what now is called a trans artist, the Danish artist Ovartaci (1894 – 1985, born as Louis Marcussen) fits perfectly in today’s identity based art discourse which is promoting an inclusive boundary free approach to the arts. Her work stands out in the impressive exhibition ‘Cobra 75: Danish Modern Art’ at Cobra Museum getting a floor of its own. Maia Kenney is impressed by the richness of all presentations at the Amstelveen museum though unsure about the way Ovartaci is framed. ‘I realized just how lonely Ovartaci was.’

At a February 1st panel discussion at De Balie, Elvira van Eijl, curator of the Art Brut Biennale in Hengelo, asked Rein Wolfs about Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam’s new collecting policy, in which the museum will try to use 50% of its collecting budget to buy artworks by women and people of color.[1] ‘I’m missing the art brut artists, the so-called outsiders, people experiencing mental illness’, she asked; ‘can’t they also claim a spot in this diverse, inclusive spectrum you’re working on?’ Wolfs’ answer was clear enough: ‘We are not a ‘Musée de l’Art Brut’ like the one in Lausanne – there are specialized museums for this.’

This exchange has been running in my mind over the past few weeks as I visited Cobra Museum to review the three-part, monumental exhibition Cobra 75: Danish Modern Art. I’ll explain why later.

But first: it’s a sumptuous show, packed to the gills with paintings, drawings, journals and sculptures by Danish modernists from abstract surrealists to CoBrA and beyond. Starting with Becoming Ovartaci, a monographic show of the artist on the ground floor, the exhibition continues upstairs with We Kiss the Earth (surrealism, CoBrA, folk art and political activism) and Je Est Un Autre, which follows the partnership and work of Sonia Ferlov-Mancoba and Ernest Mancoba. On two visits, I stayed until the museum closed because I couldn’t get enough of the rich, boundary-testing world the Danish modernists built for themselves. I recommend this exhibition to anyone interested in modernism generally, the political activism of modernists, or artists plumbing the depths of their identities.

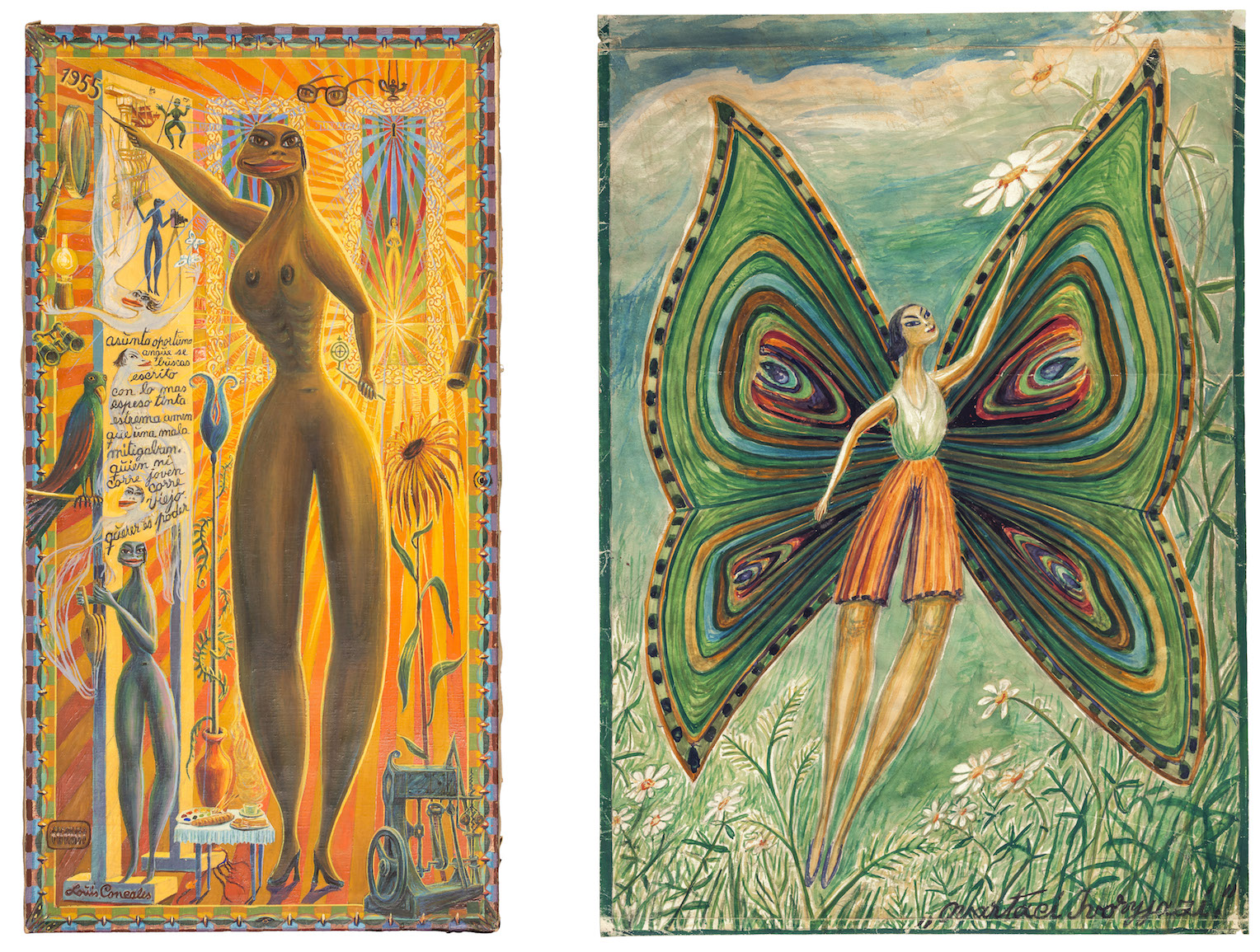

Left: Ovartaci, Untitled, undated, private collection. Photo: Anu Ramdas, right: Ovartaci, Untitled (Sommerfuglepige, Butterfly Girl), undated, private collection. Photo: Ole Akhøj

I first spent a few hours with Ovartaci (1894-1985), whom I’d first discovered (late, I know) at a shrine-like installation of her paintings, sculptures and paper dolls at the Venice Biennale last year. Her[2] work floored me as it had before, leaving me alienated from myself, pulled into a swirling other space of untethered souls. The curators of Becoming Ovartaci, Nina Rasmussen and Hilde de Bruijn, drop us into her oeuvre without questioning her. We simply land in a world where the female form is exalted, godlike: as in, insectile, lizardlike, terrifying and all-powerful.

We land in a world where the female form is exalted, godlike: as in, insectile, lizardlike, terrifying and all-powerful

Installation overview 'Becoming Ovartaci' at the Cobra Museum of Modern Art Amstelveen, photo Peter Tijhuis

Installation overview 'Becoming Ovartaci' at the Cobra Museum of Modern Art Amstelveen, photo Peter Tijhuis

There is an obvious effort to free Ovartaci from the labels forced on her by her doctors, government and biographers, who refused her gender and diagnosed her with schizophrenia; here, she can inhabit her selves with abandon and blessedly free from psychoanalysis. We encounter an installation that is calm and in some cases sublime, as in a double-sided landscape with sunset-lit horses in a golden field positioned just so that the grass blends into the reeds across Cobra’s little lake.

Ovartaci’s large papier-mâché dolls steal the show: they float a little above eye-height as beige, impassive guardians somehow animated by a slight breeze. They’re uncanny, but protective, and I like to picture Ovartaci packing one into her bike basket on her cycling outings around Aarhus. I also love Ovartaci’s electrifying abstracted depictions of spirits floating through reverberating energy fields. They’re glowing, dizzying, mesmerizing acts of transformation, a theme that builds in intensity until the entire installation seems to hum. This first exhibition sets the tone, and standard, for the rest of the show upstairs.

Running throughout the entire show is a current of fascination with the abstraction that folk and indigenous traditions can offer – of course many modernist movements felt free to cherry-pick reference objects without understanding their cultural or ritual significance. The exhibition tries to democratize these fascinations: if folk art is just art made by people, all art is folk art.

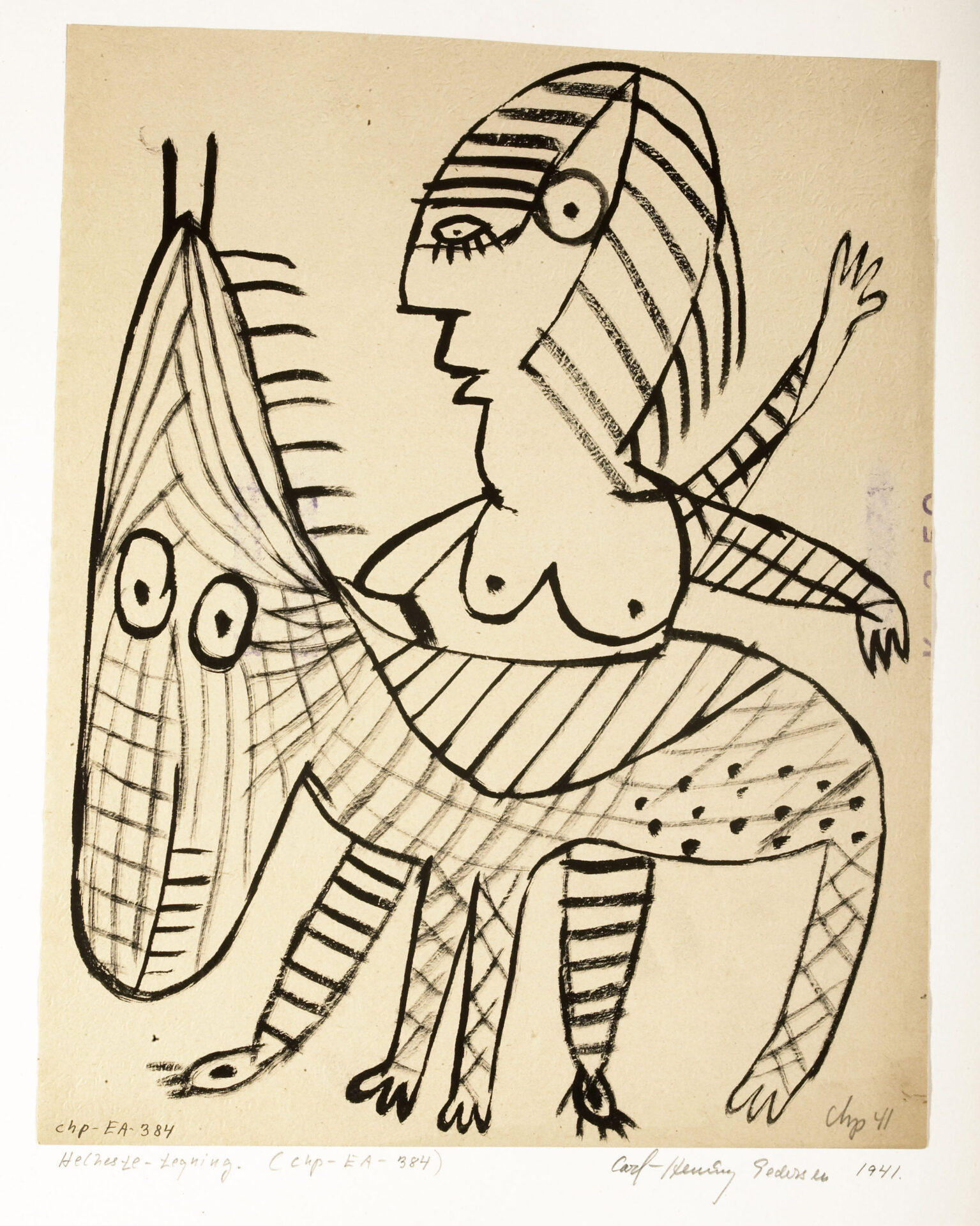

Rita Kernn-Larsen, The Women's Uprising (Kvindernes Oprør), 1940

Cobra Museum is at its strongest, in my opinion, when artists’ and movements’ social and political voices are centered. In the first part of the exhibition, We Kiss the Earth, Danish surrealist icon Rita Kernn-Larsen (1904-1998) is shown with her 1940 painting Kvindernes Oprør (Women’s Uprising), the Danish title for the Ancient Greek comedy Lysistrata, in which wives refuse to have sex with their warring husbands until peace is declared. The painting is a dance of straining branches and exposed and suggestive notches. It’s a magnificent declaration of refusal to become an othered body, all the more poignant at having been painted at the start of the war in London, where Kernn-Larsen and her Jewish husband Isak Grünberg had fled. Further into the exhibition, a wall of drawings for the journal Helhesten by Carl-Henning Pedersen turns the Norse goddess Hel’s three-legged demon-horse, an omen of doom, into a cartoonish satire of the Nazis’ preoccupation with Viking ancestry. Movements and collectives fall apart, but their fervency can still be felt seven decades later.

The painting is a dance of straining branches and exposed and suggestive notches. It’s a magnificent declaration of refusal to become an othered body

Carl-Henning Pedersen, Helhestetegning (The Hell-Horse), 1941, Carl-Henning Pedersen & Else Alfelts Museum. Photo: Mingo Photo, c/o Pictoright 2023

Installation overview 'We Kiss the Earth' at the Cobra Museum of Modern Art Amstelveen, photo Peter Tijhuis

But what of the artists whose fervency makes us uncomfortable, requires us to meet it with strength and openness? ‘Je est un autre’, wrote poet Arthur Rimbaud in 1871; the person I present is not who I am. To bring the two iterations of the self (the internal and the social) into one is an artistic endeavor shared by many of the artists in this exhibition. Ernest Mancoba (1904-2002), for instance, is portrayed by the show’s curators as a man searching for himself, learning of himself through the eyes of the colonizer. Mancoba was a South African avant-garde sculptor and painter who left his home country in 1938, ‘when I understood that I would not be able to become either a citizen or an artist in the land of my fathers’. Once in France he experienced much brighter prospects as an artist and in love: there he met his lifelong partner, Sonia Ferlov. But he was imprisoned in French camps during WWII and ostracized by the Danish artistic community afterwards, ever the other, a body unwanted. Though he credited European exoticizing texts on African art as formative to his blossoming knowledge of artistic practices from indigenous and Black cultures, he knew his art would always be judged with the same primitivist, racializing eyes.

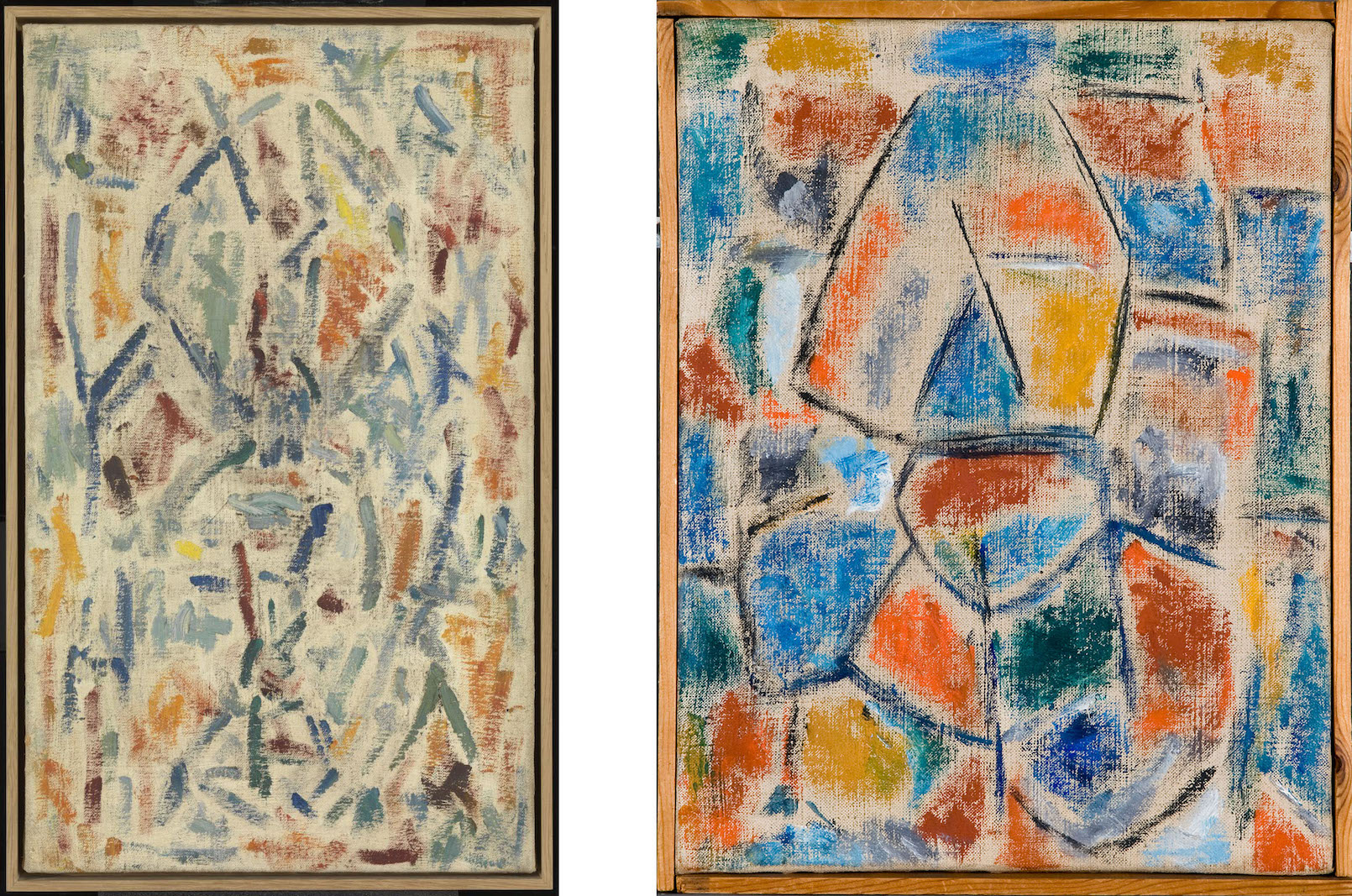

Left: Ernect Mancoba, Untitled, 1957, Tate Modern. Right: Ernest Mancoba, Untitled, 1950, Museum Jorn, Silkeborg , c/o Pictoright 2023

His sculptures, automatic drawings and dry, scraped oil paintings are defiant, the work of a man determined to explore his own fascination with the ways figuration can infiltrate the abstract. Shapes and forms of African sculptures are repeated as something like a mantra, stitched into the very fabric of abstraction. Still, I’d have very much liked to see more of Mancoba from his own perspective. ‘Art is not a cause of pleasure or delight’, he writes in one illuminating note: art is the result of discomfort, of urgency, of the need to make. If it is beautiful, that is a secondary attribute which should not obscure its meaning. To make art is to create from within the self; Mancoba’s automatic drawings demonstrate the need to find and express the ‘I’.

‘Art is not a cause of pleasure or delight’, Ernest Mancoba writes in one illuminating note: art is the result of discomfort, of urgency, of the need to make

Installation overview 'Je est un autre - Ernest Mancoba and Sonja Ferlov' at the Cobra Museum of Modern Art Amstelveen, photo Peter Tijhuis

Installation overview 'Je est un autre - Ernest Mancoba and Sonja Ferlov' at the Cobra Museum of Modern Art Amstelveen, photo Peter Tijhuis

Which brings me back to my first point, and Wolfs’ refusal to actively collect outsider artists for the Stedelijk Museum. I couldn’t quite put my finger on what exactly was bothering me about Cobra 75 until I walked back downstairs and realized just how lonely Ovartaci was. Kept in a psychiatric hospital until her death, refused gender-affirming care… and in death, categorized as an outsider artist, continuously misgendered and wrongfully psychoanalyzed, Ovartaci is only just receiving a critical examination of our role in excluding her. And while I appreciate Cobra’s careful descriptions of her work and life (especially in the catalog), there are two things I couldn’t bear about the show.

The first is that Cobra is selling a book by Brian B. Hansen (Ovartaci: The Signature of Madness, 2022) that is in many senses transphobic; this undermines the effort to free her from 70 years of men psychoanalyzing her and pathologizing her needs. Hansen flippantly erases Ovartaci’s entire expression of gender identity and her demand to be given the right to a gender reassignment (in a footnote!!) in order to psychoanalyze her as a male artist. Well, his Freudian argument crumbles if she reclaims agency over her pronouns, name, or transgender identity.

Secondly, I realized that, though it’s a sensational exhibition and probably installed downstairs to attract visitors, by showing Ovartaci apart from her compatriots, her outsider status is affirmed and perpetuated. The subjects that preoccupied the surrealists – eroticism, transformation, the subconscious, the occult –and CoBrA – spontaneity, freedom and childlike experimentation – are Ovartaci’s as well, and I wished they could weave a web together. Rebellion and dealing with the unwanted body: these are the true themes of the exhibition. What new insights could we have gained had these been the golden threads?

By showing Ovartaci apart from her compatriots, her outsider status is affirmed and perpetuated

When we sit in outdated designations like ‘primitivism’ (defunct) or ‘art brut’ (still, perhaps, the only space for artists who experience diagnosed difference and disability) for so long, we lose the chance to make connections, to find affinities and beauty in social movement. To say an outsider artist doesn’t belong in our museums is to agree with those who would keep them apart. Cobra has made a bold step in the direction of rewriting othering histories. But I challenge Cobra, the Stedelijk and other museums of modern art to position themselves boldly. Throw open your doors and toss out artificial categories that prevent us from forming communities of resistance.

[1] As discussed in Sarah Vos’ documentary White Balls on Walls (2023)

[2] I use she/her pronouns for Ovartaci. She spent years petitioning the Danish government to give her gender affirming care, not entirely successfully. Though she returned to male pronouns in the last year or so of her life, and I assert that any transgender person who detransitions must be given the respect of using their chosen pronouns, I wish in no way to be associated with the problematic refusal to ever use she/her by the Danish government, the Ovartaci Museum in Aarhus, and some art historians even today.

Maia Kenney

is an independent curator working on promoting marginalized voices in cultural institutions