You are NOT invited – Rasmus Myrup’s Salon des Refusés at 1646

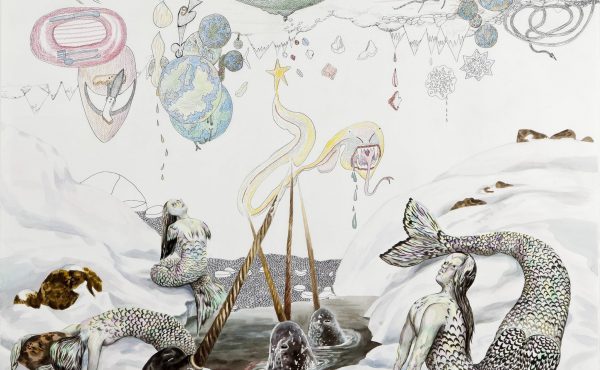

‘Did I interrupt something?’ Upon her entry into 1646, Karmen Samson finds herself in a scene filled with creatures that appear to have paused their activities. Danish artist Rasmus Myrup invited these beings, inspired by ‘non-normative’ characters from Norse mythology, to his ‘Salon des Refusés’: an exhibition that skilfully juxtaposes Nordic ancient folklore legends with capitalistic systems.

Odin and Thor, their names surely echo in the corridors of your mind, do they not? Were they not the revered and celebrated deities, heroes whose tales unfolded in the vast tapestry of myth? Indeed, they originate from Norse mythology, a complex system of beliefs with interconnected tales about an array of creatures. But what about female, queer, or transgender storylines? While they do exist within Norse mythology, they are not the glorified gods, or cosmic elements personified as beings. No, sadly these ‘non-normative’ characters are often ascribed to the roles of outcasts. Their tale is less familiar and often forgotten, regardless, they still reverberate in the shaping of contemporary patriarchal norms. Danish artist Rasmus Myrup embarks on a quest to retell these overlooked stories, seeking a deeper understanding of these marginalised antagonists. He does so by inviting these mythological figures to the exhibition Salon des Refusés held at art space 1646 – an exclusive gathering, I regret to inform you, to which you are not invited.

The atmosphere within 1646 exudes a serene minimalism, characterised by stark white light and an absence of any noise. What immediately captivates attention are the 23 sculptures positioned unstrained across two rooms. At first glance, these sculptures evoke a familiarity reminiscent of fashion mannequins typically found in retail stores, serving as representations of the normative human form. Yet, upon closer inspection, a deviation becomes evident. Tails, elongated limbs, and missing body parts redefine these figures, transforming them into entities beyond the confines of typical human anatomy. Adding to the intrigue are their dynamic poses, seemingly captured amid action, suspended in time. All of this makes me wonder; did I interrupt something? Upon my entry into this space, did the harsh lights flicker on, the music cease, and these creatures pause their activities? Their postures hint at conversations, flirtations, dances, and singing. The scene imposes a suspense of waiting for something… Something to come? Or rather someone to leave?

The solo exhibition of Rasmus Myrup covers multiple centuries of Nordic ancient folklore legends in a ringing contemporary manner. It skillfully juxtaposes the tales with the backdrop of capitalistic systems, highlighting their historical role in fostering dogmatic perspectives on gender and associated characteristics. The exhibition explores a thematic strand that delves into the social and cultural impact of myth construction, particularly those entailing misogynistic, homophobic, and cis-centered worldviews. It challenges and questions these worldviews through non-verbal expressions using materials and forms of fashion.

The creatures are made of natural materials in tandem with their mythological heritage and wear custom-made clothing that expresses their individuality and personalities in a stereotypically subversive way. Take for instance Saggy Tits, (Slattenpatten) a hunting woman renowned for her unique characteristic of exceptionally long breasts. Legend has it that she slings her breasts over her shoulder, enabling her to nurse a child even when the child was being carried on her back. In moments of danger, when chased by other hunters, she did the same, ensuring they wouldn’t impede her as she fled along the coastlines. Myrup made her body from driftwood, a direct material reference to the setting where her story took place. In an accompanying booklet Myrup explains “this is a material that itself feels like a magical apparition, with its sanded edges and holes, and an old Norse symbol of primordial life.” Notably, it’s not her wooden body that embodies her iconic features, but her clothing that vividly represents this. The silver dress features a bust area that seamlessly transitions into a tubular padded section, elegantly draped over her shoulder. It conveys a stylized and refined image, quite contrary to the wild and untamed aura evoked by the tales. Saggy Tits stands here with dignity and pride. Rather than the mannequin simply showcasing the garments, the mannequins become an extension of the garment itself. Material and cloth are together the embodiment of the myth.

Typically, women are in myths stereotyped as passive or submissive figures, emphasising qualities like gentleness, nurturing, and dependence on male figures. These stories tend to disproportionately highlight the youth and beauty of female characters, reinforcing patriarchal ideals and expectations. Conversely, women who don’t conform to these standards are cast as evil figures or witches, wielding their supernatural powers for malevolent purposes. Such stereotypes contribute to the perpetuation of fears surrounding powerful and independent women. The myth becomes a tool for social control, framing certain behaviors as acceptable and others as undesirable. Women who resisted male authority were subjected to ridicule, capture, and often violence.

As much as these two sides differ, there is a common denominator; a lack of agency. Whether this lack stems from little independence, heavily relying on male characters for guidance or decision-making, or women not obeying to these decision-making men, both reinforce the stereotype that women should be controlled. Myrup displays a re-telling of these mythical tales, incorporating a more diverse perspective. The story remains the same, but in Myrup’s version, the division of roles and their understanding is completely different.

Take for instance, Milk Hare, mischievous milk thief who serves as a companion to witches. The whimsical Milk Hare would suck milk from the cow’s udder and spit it into the witches’ milk jugs. In Myrup’s interpretation of the tale, the Milk Hare had drunk too much, got tipsy, causing a bit of chaos in her usual duties. Sobered up, and to redeem herself, she pursued studies abroad in Paris. “Now, she is milking that story every chance she gets” tells Myrup. This redirected storyline explains why she is wearing a t-shirt that is embossed with “Paris” all over it. However, this wasn’t her more practical fashion choice, Myrup added more to the story “she sorts of forgot that she might get cold, so she ended up borrowing a jacket from The Forest Bussy.”

Forest Bussy, as the myth tells us, was a mischievous trickster dwelling within the forest, instilling fear in many people. The eerie creaking sounds of trees blowing in the wind and rubbing together was often assisted with him, labelling this unsettling sound as “his giggle.” Myrup however, saw him differently and described him as a cute gay male with a difficult yet infectious laugh.” In his interaction between the Milk Hare and himself, Myrup explains that “he was more than happy to lend her his rhinestone distressed denim trench-coat, which made sense for his “entrance”, but at this point, he was more bothered by the fact that it covered his greatest asset: his ass.” Myrup didn’t just revisit their stories; he united them, imbuing each with vibrant social traits and distinct personalities. He dressed them in ways that challenge the stereotypical images crafted by dogmatic ideologies. This process creates a worldly experience where materials converge with one another, giving rise to alternative narratives and fostering a reinforced sense of agency.

These reinterpretations are not mischievous or spooky; rather, they are cheeky, witty, and instantaneous, rendering these figures more endearing than ever before. Unfortunately, the accompanying booklet fails to include other additional anecdotal stories. A pity, as I yearn to know them better, to hear about their everyday experiences and small talks.

Then, I remind myself that I’m not part of their group; their gathering wasn’t an invitation extended to me. I am an uninvited guest, fortunate enough to witness a glimpse of untold stories lingering in the silent air. In the Salon, Myrup employs materials as a direct reference to South Scandinavian folklore and Nordic history. Simultaneously, he incorporates contemporary fashion and custom-made outfits to offer a fresh mode for expressing diverse personalities. The result is a material dialogue delving into the changing narratives surrounding gender, viewed through feminist and queer lenses. In this artistic realm, Myrup acts as a guardian spirit, lovingly watching over these Nordic mythical figures, seeking to shield them from further persecution. Nevertheless, Myrup remains optimistic that individual experiences, emotions, and perspectives will aid in interpreting these myths. He places trust in the open-mindedness of visitors. And perhaps, when they do, an invitation will be extended, with the bubbly Forest Bussy greeting them at the door, and the Milk Hare offering a drink to share.

Salon des Refusés by Rasmus Myrup is on view at 1646, The Hague, until April 7

Karmen Samson

is modebeoefenaar en onderzoeker met interesses in materiële cultuur en museologie