Perra Perdida at Lulu

Looking at one of Mexico City’s (many) new apartment galleries, and a recent exhibition that works its context. “The work happened fast, but the thinking was slow,” say artists Allison Katz and Camilla Wills, whose collaborative project Perra Perdida is currently on view at Lulu.

Deep in Mexico City’s Colonia Roma, artist Martin Soto Climent and independent curator Chris Sharp run Lulu, a project space in the front room of their apartment. The name is an homage to Lulu’s juice stand down the street. When I visit on a sunny Friday, Sharp waits in the apartment’s inner courtyard, sunglassed and engrossed in laptop work. Lulu’s casual professionalism is immediately appealing: the apartment is humble, blends into the barrio; Sharp is relaxed, gives each guest a personal tour. But the tiny project space is impeccable – a perfect white cube nestled in a typical Mexico City home.

Mexico City’s art world is self-organizing rapidly, with swelling numbers of project spaces, apartment galleries, and alternative institutions run by artists.

Mexico City’s art world is self-organizing rapidly, with swelling numbers of project spaces, apartment galleries, and alternative institutions run by artists (many of them international, drawn by Mexico City’s energy and cost of living). Amidst the punk vibes of Bikini Wax or the post-internet focus at Lodos Contemporaneo and No Space up in the San Rafael neighbourhood, Lulu distinguishes itself through Soto Climent and Sharp’s dedication to their mid-career (or nearly) contemporaries.

Lulu began intuitively, driven by their mutual desire to commit to one place after being pulled around the globe for work. Soto Climent and Sharp are now drawing on these established networks for Lulu’s programming, exhibiting international artists often for the first time in Latin America. In a vague attempt to summarize Lulu’s programs: there is a strong respect for material conversations, and often a rather complex lightness or humor. Last summer Lulu featured Willem de Rooij’s Bouquet IX (2012) – a monochromatic flower arrangement refreshed daily – and many of the city’s younger artists personally thanked them for the opportunity to see the work in Mexico.

When I visited in December, a new exhibition had just opened: Perra Perdida, a collaborative venture by Allison Katz and Camilla Wills, both London-based. Sharp introduced the two, suspecting (correctly) that each artist’s idiosyncratic logic would find its match in the other. This is Lulu’s first site-specific exhibition – the first time the artists have come to Mexico City rather than sending work from abroad. For Katz and Wills, the exhibition produced an unusual set of conditions from the start: for one, the artists barely knew each other when they began researching the show. They spent over a year on “field trips” around London building shared references. As such, the exhibition in its final form is almost a metaphor for the meandering, irregular genesis of an art work or an idea.

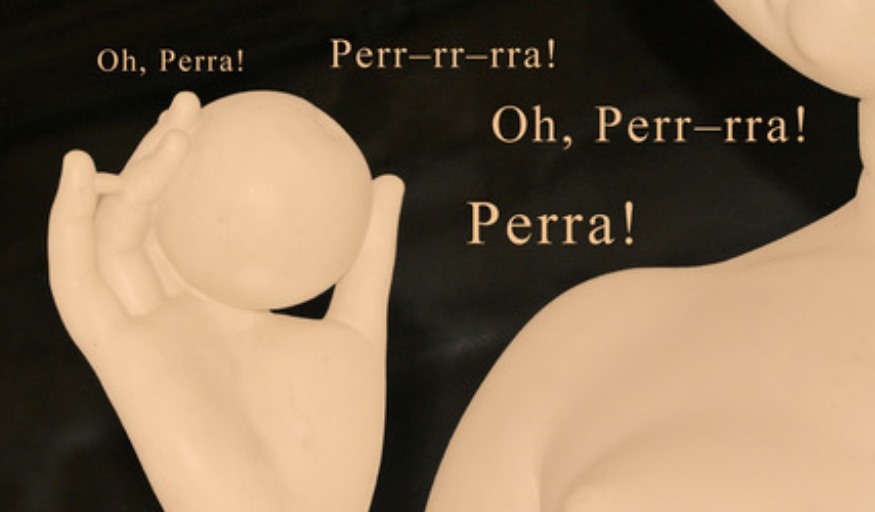

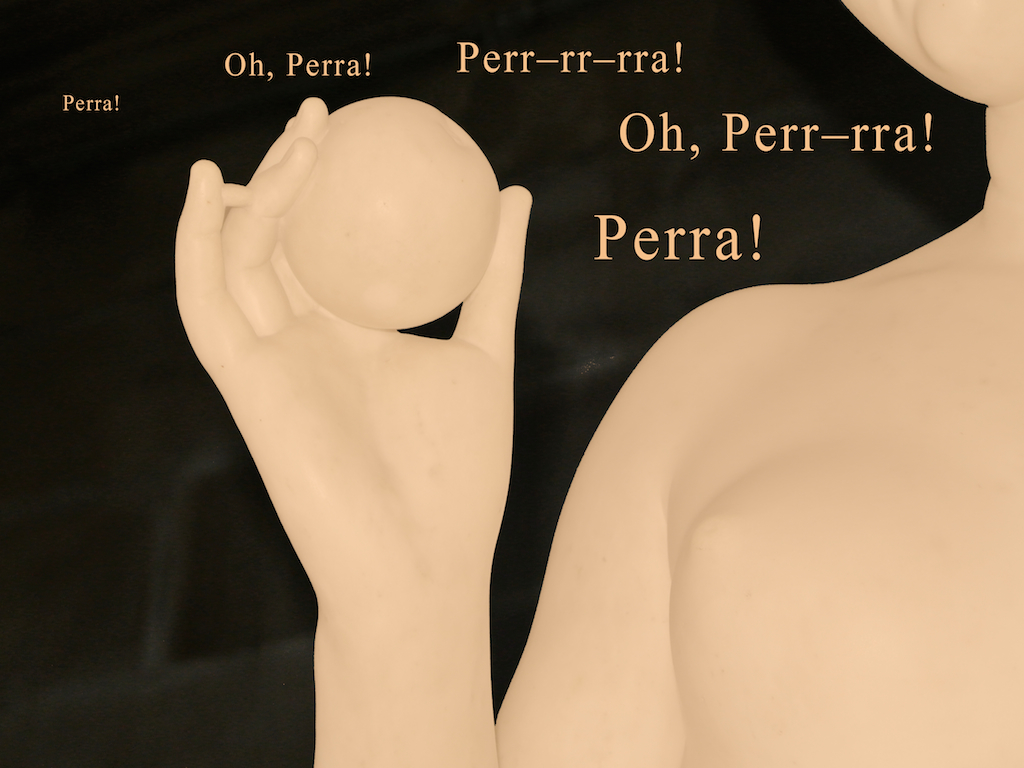

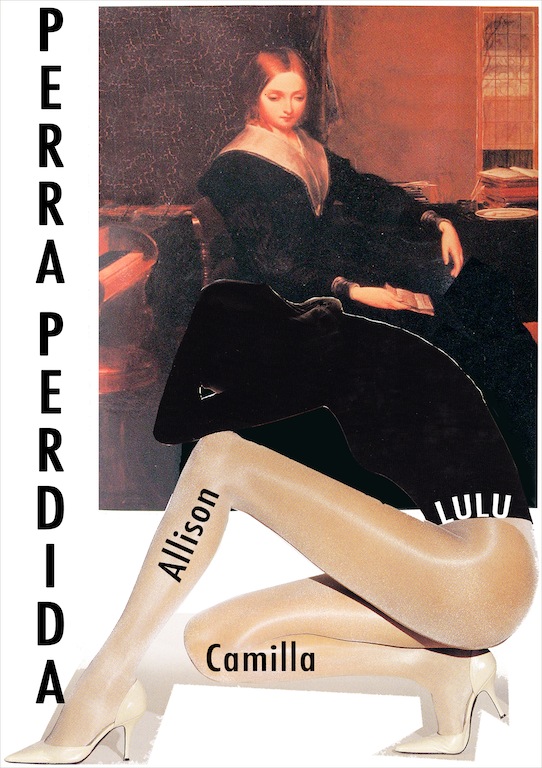

In Lulu’s main space, Katz and Wills present a series of collaged posters that mimic the form of the lost dog notice, as well as a short looped video made on location. Then, across the apartment, the artists went beyond Lulu’s existing boundaries to fresco the walls of Soto Climent’s studio, replicating the posters in a wallpaper-like pattern.

Between these works, the artists weave a web of margins, inversions, and relationships. With a lost dog poster Katz found in Quebec in 2011 as the starting point, the exhibition unfolds through the artists’ associative and metaphoric reasoning, and ultimately comes to address questions of the original and the copy, of authorship, inter-species subjectivity, the presentation of margins as the centre, how information is delivered, and where importance is located. Who thinks about a lost dog poster? One thinks about the dog. The poster defers to the thing itself, is a stand-in and a representation; this being at the core of all image-making. In fact, much of Perra Perdida’s content lies in forms that are most often meant as accompaniments (the poster, the title, the signature, wallpaper); we are challenged to look at them rather than look through them. The exhibition’s deferral of “true” content is not emptiness, but a re-orientation of expectations.

Rhythmic and repetitive naming propels the exhibition and the viewer: perro perdida, parroting, parody, perroquitas. Bitch, leash, loss, Lulu. Allison and Camilla, nearly inversions of each other. The posters introduce the self-conscious and recurring use of the artists’ first names, and the exhibition’s vital information (title, date, venue). Sharp’s phone number is placed on one poster, squarely beneath the lost bitch; all involved are implicated. Repetition also performs as mockery or parroting, and the inversions of agency this can set forth. Throughout the exhibition, acts of calling and labelling establish focal points where there might otherwise be none, such as to the affect of coded words like leash and bitch, and to the surprising subversion of liberally applying one’s own name to one’s work. This relentless wordplay creates an unsettling landscape of ownership, loss, desire, and aggression, which may actually be the project’s most potent contribution.

This relentless wordplay creates an unsettling landscape of ownership, loss, desire, and aggression, which may actually be the project’s most potent contribution.

The language of leashes and bitches is exaggerated in the exhibition’s accompanying text by Mexico City-based writer Gabriela Jauregui, and then folded back into the exhibition via the video. Both text and video relish in the surface: Jauregui’s text skims through a litany of words and fragments; it reads like free association, moving from the restraint of the leash to the paradoxical qualities of plaster, its porosity and its hardening. The text fits easily alongside the smooth surface of a Photoshopped poster and the panning camera recording Leash Seeks Lost Bitch (Perraquitas), which slowly reveals the languid, costumed artists lounging at Lulu.

Down the scruffy hallway in Soto Climent’s studio, the exhibition’s most involved work, a fresco, has absorbed the paint, retaining the wall’s cracks and blemishes. The patterned wall painting is composed of copies of the posters in the other room; but, in paint, the posters’ information is lost. They become decoration. Katz and Wills derived the pattern from a popular image of World War II-era silk scarves used as propaganda. This kind of small disruption to the fresco’s visual pleasure introduces a complexity and uncertainty to the decorative surface, much in the same way the informational text punctuates the glossy posters – seemingly at odds. Throughout, Katz and Wills seek the political in what may be seen as superficial. It is political to say, look at this.

Perra Perdida questions the primary positions of our production, not just the content. Each part of the exhibition and each contributing voice is reliant on the others, forgoing autonomy and foregrounding the schizo-subjectivity that emerges when making is a true collaborative and open-ended conversation. Jauregui’s text, for example, though not technically a work in the exhibition, is imperative to the project’s depth. Soto Climent and Sharp’s presence, too: Sharp was the curatorial matchmaker between the artists; then, Soto Climent expanded the network, calling on his uncle to teach the artists the traditional Mexican cactus-based painting technique they employed for their fresco. With Perra Perdida, Lulu makes a strong case for models of working through affinity, both in running an institution and making an exhibition. I doubt such a project could have existed anywhere else.

Perra Perdida runs until February 4. Lulu’s next exhibition, of Swedish artist Nina Canell, opens later in the month. The rest of 2014 at Lulu will see solo projects by Aliza Nisenbaum, John Smith, Lisa Oppenheim, and Michael E. Smith. For more: http://luludf.tumblr.com/.

Kari Cwynar