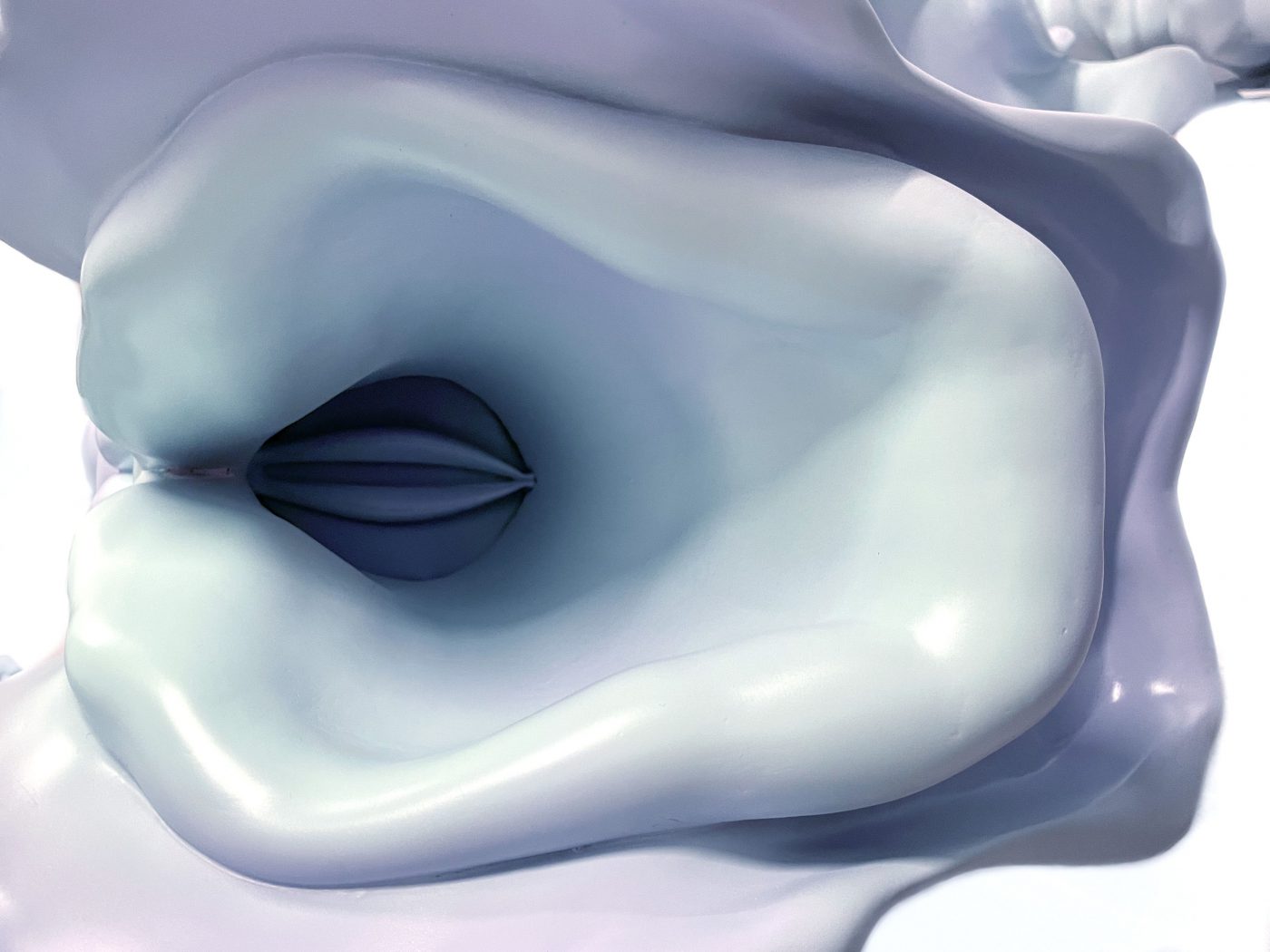

Femke Herregraven, Twenty Birds Inside her Chest, 2021, Gwangju Biennial, Gwangju

Diving with a coffin on your back – A conversation with Femke Herregraven and Defne Ayas

How to organise a Biennale in times of a pandemic? Despite Covid-19, the 13th edition of the Gwangju Biennale has recently opened its doors. Participating artist Femke Herregraven and Biennale co-artistic director Defne Ayas (with Natasha Ginwala) speak with Maarten Buser about voices emerging from catastrophe.

The first time we spoke, Femke Herregraven (1982) told me one of the things she likes best about being an artist, is the possibility to be occupied with one theme for a longer time. Her fluid oeuvre is a good argument both in favour of and against that claim: her installations and other projects share themes and interests, and one work can be a starting point for the latter. Even her long-time interest in catastrophes is far from a neatly demarcated theme, but rather an entanglement of subjects, ranging from economics to human evolution (which we’ll touch upon more extensively in this conversation). Her newest work, Twenty Birds Inside Her Chest (2021), is a sculptural sound installation, as well a part of the ongoing research on catastrophes. It is shown during the 13th edition of the Gwangju Biennale (South-Korea), which is curated by Natasha Ginwala and Defne Ayas; the latter joins our Zoom conversation to shine a light on the shared themes between installation and Biennale, and on how things – of course – went differently this time.

First of all, I’m just really curious: is the Biennale actually open to the public? The Dutch museums and art spaces are still closed due to the Covid-19 lockdown. Also, could you tell me more about the central themes of this edition?

‘Exhibition spaces, museums, theatres, and concert halls are currently all open in South-Korea, as the infection numbers are very low; about one to two cases a day in Gwangju. The Biennale had to be postponed twice, with the last postponement taking place due to its special status as an “event” en par with a sports or a political event. The exhibition is very well attended at the moment by local audiences, unfortunately we couldn’t have visitors from abroad because of the two-week quarantine requirement. We recorded educational and virtual tours of the exhibition, which can be viewed online, on our website and the Vimeo account of the foundation.To give a bit of an introduction, we set out to examine the entire spectrum of intelligence, through the rapidly shifting registers of organic and inorganic intelligence. The exhibition delves into a broad set of cosmologies, activating multitudinous forms of intelligence, planetary life-systems and modes of communal survival, as they contend with the future horizon of cognitive capitalism, algorithmic violence and planetary imperialisms. The Biennale is basically a big construction that is accomplished in collaboration with sixty-nine artists and collectives, and over thirty thinkers, poets, scientists and journalists. Femke has been with us since the outset and throughout the journey. She was one of the twenty artists we could invite to join us in our two artist research trips before the pandemic broke out. Femke, do please tell us about your research, trip to and experiences on Jeju. (laughing:) I can only describe that as a love affair between you and the island.’

Femke Herregraven, Twenty Birds Inside her Chest, 2021, Gwangju Biennial, Gwangju

Femke Herregraven, Twenty Birds Inside her Chest, 2021, Gwangju Biennial, Gwangju

‘My installation, Twenty Birds Inside Her Chest, is situated in the watery commons of Jeju and is a continuation of my research on the aquatic voice to counter the sound of catastrophe. My installation Diving Reflex (Because We Learned Not To Drown We Can Sing) for the 2019 Prix de Rome explored the diving reflex and the emergence of speech as a prelude to this new work. Back in 2019, I developed the character of Elaine: an aquatic creature whose voice emerges during the catastrophic downfall of the Last Man. Elaine is finding her voice: she murmurs, stammers, rasps and babbles sounds that can’t be named yet. She constantly searches for ways to adapt her breathing, voice, and singing under conditions of catastrophe. I named her after Elaine Morgan, a feminist writer who developed the controversial aquatic ape hypothesis as a missing link between primates and humans. This hypothesis rejects competition as the driving force of evolution and instead centralises the role of women, children, care and the aquatic environment. An aquatic past could explain why children feel naturally comfortable around water and why we humans have the “diving reflex” and certain other primates do not. The evolution of this reflex created a strong neural path between our throat, mouth, and brain and this path is believed to be the reason why our early ancestors were able to hum, start singing, and eventually develop speech. Singing originates from learning not to drown. It was very special to continue this research on Jeju, an island with a traumatic history where resilience and survival are very much present as well. The haenyeo – the female freediving community of Jeju – are an example of that. For me, they are our contemporary Elaines. The haenyeo have for centuries gathered and sold seafood to provide for their community. Diving is physically very hard and not without risk. On the island, it’s said that a haenyeo leaves her life behind when going to the sea. How they face their own mortality on a daily basis is reflected in another saying that I heard of when visiting Jeju: “Haenyeo dive with their coffin on their back.” Diving represents a transitional space between life and death.’

‘The island and especially the haenyeo have become a tourist attraction recently, with plenty of the photographic clichés of strong, female divers circulating around. But Femke’s work goes much deeper and draws upon the communal intelligence in the matriarchal structures of these communities and their relationship with their watery surroundings. This is an extraordinary endeavor really, also its archival ambition.’

Femke, could you tell me more about that archival ambition?

‘The communal intelligence and survival of the haenyeo stems from their adaptation to water. For centuries, a specific breathing technique was passed on by the haenyeo to their daughters. When they resurface and inhale and exhale with force, this produces a kind of whistle named the sumbisori. Even today, the haenyeo refuse to use oxygen tanks which would allow them to stay longer under water but could also make them greedy and disturb the balance of the ecosystem. Their dive lasts only as long as one breath. By accepting the limitations of their own body, rather than overcoming them, they protect other bodies and species around them. Also, their observations of how the underwater ecosystem changed over centuries provides them with a deep knowledge of the sea. Twenty Birds Inside Her Chest celebrates this communal aquatic intelligence and survival. I was interested in how the fragility, resistance and collectivity of Jeju’s aquatic voice could be documented and preserved. The first step was to initiate a sumbisori sound archive, especially because many mothers want their daughters to build better lives somewhere else so the aging community and their voice is slowly disappearing. During a small ceremony commemorating the victims of the Jeju Uprising massacre of 1948, I met some survivors and one of them offered to help and got involved in the project. He runs a community project that is concerned with the environmental pressure concerning the local shoreline and felt connected to the project. He introduced his cousin, a haenyeo, and from there the collaboration started. I also worked again in close collaboration with composer Benny Nilsen, just as we did for Diving Reflex (Because We Learned Not To Drown We Can Sing). During the pandemic he travelled on his own to Jeju – because I was having a baby – to make the first sound recordings. It was technically very complicated. We had to design a floating device that was constantly recording. The device was being steered around the haenyeo by another diver. It was necessary to be able to record the sounds without the interference of using a boat, both because of safety for the haenyeo but also in order to capture an as clean representation as possible of the sumbisori while the haenyeo were diving and resurfacing at the sea.The sumbisori archive is a long term project and will eventually be donated to the haenyeo community. From the recordings we made so far, the new work for the Gwangju Biennial was developed. In this immersive installation, an aquatic choir of larynxes is situated inside a large circular structure, a reference to the bulteok, the haenyeo’s traditional communal meeting site for exchanging knowledge and skills, rituals, and decision making. The visitors can sit inside the bulteok between the singing larynxes and experience what Defne called the “orgasmic choir” (laughs). Placed underneath the larynxes are three replicas of a Dutch harpoon that was found in a dead whale’s body which washed up on the Korean shoreline 350 years ago. Shortly before, a Dutch VOC ship had shipwrecked on Jeju island and one of its survivors, the VOC accountant Hendrick Hamel, wrote in his journal how one of his crew members had recognised the harpoon due to the initials W.B. He remembered seeing the same harpoon when he worked as a 12 year old boy on ships of the Dutch-Greenland fishery around Nova Zembla where Willem Barentsz hunted for whales. In a later chapter that I’m working on, the harpoon will be returned to the Dutch shoreline by the aquatic choir.’

When Defne and I were speaking about the plans for the Biennale for the first time I played a sound file to her. It was the sound of my mother breathing while her lungs were filled with water. It sounded like seagulls. While listening to the sound, I said to Defne it was as if there were “twenty birds inside her chest”

Femke Herregraven, Twenty Birds Inside her Chest, 2021, Gwangju Biennial, Gwangju

Femke Herregraven, Twenty Birds Inside her Chest, 2021, Gwangju Biennial, Gwangju

Something that indeed struck me while reading about the matriarchal community of Jeju, is that the women are the breadwinners, take care of the children, and share their knowledge with each other and with younger generations. What is left for the men to do?

‘‘(laughing out loud, along with Ayas:) Housekeeping! (returning to a more serious tone:)According to an oral myth, Jeju was created by a grandmother goddess named Seolmundaehalmang so the island was shaped from matriarchal wisdom to begin with. Regarding the haenyeo, it seems there are several gender related explanations for their emergence. One of them is that women have more body fat which gives them more buoyancy and insulation while diving. Another one is that historically the taxes were much higher on men for gathering and selling seafood. The communal survival of the haenyeo is not only about overcoming the moment of dying while diving, but also overcoming death during political upheaval and violence. Under the Japanese occupation in 1932, when a group of haenyeo were imprisoned and killed during protests, others stormed the police station to liberate their sisters. Despite the dead bodies of victims of the Jeju Uprising massacres in 1948 floating in the seawater, the haenyeo still had to go back into that sea of death and find a way to make a living. When a school burned down in 1950, they donated their income from selling seaweed to the school’s reconstruction fund. For the haenyeo, survival and resistance have always been communal.’

‘I should also mention here that we have included Femke’s installation in the final gallery of the Biennale Hall, which we titled Matriarchy in Motion, where matriarchal cultures and knowledge acquired through feminine wisdom(s) circulate generously, amid the unveiling of “dissident goddesses” in historical paintings of dragon queens from Korean mythology. Liliane Lijn’s Electric Bride speaks to techno-feminist futures, how the “natural” body becomes mechanized and hybrid. Lynn Hershman Leeson’s living sculpture addresses bacterial agency, sustenance, and morphologies that “twist” the very idea of woman. Vivian Lynn calls for attention to the recesses of our brain. And Femke places us underwater and in the larynxes of the haenyeo, evoking an acoustic environment filled with aquatic , almost orgasmic, tonalities. Across the gallery, the “maternal” body acts beyond reproductive duties, moreover it processes and vanquishes societal ruptures. And also, Gwangju Biennale commemorates the spirits of the Gwangju uprising from 1980. It basically acts as a living memorial and addresses its significance every two years. In that sense, we connect the spirits and civic experiences of Gwangju, be it now or historic, to this island of Jeju and its traumatic experiences, but also with the rest of Asia and the world.’

As Defne said, the Biennale focusses on a variety of intelligences, often bringing together new technologies with knowledge that was passed on for generations. How the haenyeo work, reminds me a bit of flocks of animals, as well how that influenced the decentralized artificial intelligence that is known as swarm intelligence. Also, the sound composition of Twenty Birds Inside Her Chest is produced by speakers in the larynx sculptures, that react to each other, don’t they?

‘From the very beginning, I imagined the haenyeo as an aquatic choir, but in line with their whistle and the title of the work, they can also be imagined as a flock of birds. The sound composition emitted by the larynxes spatially recreates the dynamics of a diving haenyeo group. Each haenyeo dives according to her own rhythm and communicates with the other women with her own voice and whistle. This whistle is unique to each diver and signals the resurfacing of that diver, of making it back to life. In the sound recordings, hundreds of edits were made to eliminate the excessive sound of water and to accentuate the sumbisori. Inside the installation, the spatial acoustic play between the haenyeo is recreated by the group of larynxes that seem to call out to each other. This aquatic choir is situated inside the bulteok structure which emits a quadraphonic composition of field recordings and sound interventions originating from the island and beyond.’

You’ve had quite an intensive year, not only because of the pandemic, but also because your mother passed away after being sick for a long time, and you became a mother yourself. How did this influence this new work?

‘When Defne and I were speaking about the plans for the Biennale for the first time I played a sound file to her. It was the sound of my mother breathing while her lungs were filled with water. It sounded like seagulls. While listening to the sound, I said to Defne it was as if there were “twenty birds inside her chest”. We immediately knew that this should be the title for the work. During its development, I was simultaneously taking care of my mom. While working on preserving the haenyeo communal voice of survival, she started to loose hers. At the moment that she entered a space between life and death, she and the work became very intertwined. During my mom’s last weeks, I explained the new work to her and that the seagulls in the sound composition were actually her own lungs. She immediately felt it was also a way to deal with her imminent passing. My daughter was also born around this time, which deepened the relationship with my own mother and my ideas of motherhood. My daughter is starting to discover her own voice now; you must have heard it in the background during the interview. In a way, her voice was also born out of a moment of catastrophe. I’ve got a real life babbling Elaine around me the whole time now.’

Gwangju Biennale, until May 9 2021.

Maarten Buser

is dichter en kunstcriticus