Roos Pris in her Studio. Photo: Sanne Sanders.

Painting as a Platform for Community – in conversation with Pris Roos

While many different curiosities come together in Pris Roos’ brightly coloured canvases and installations, there is one that clearly stands out: a strong sense of community. Alyxandra Westwood visits the artist in her studio in Rotterdam: ‘I hope that people can really become part of the gathering, moment, or story I have depicted on the canvas.’

As I am on my way to her studio located in Rotterdam-Zuid, I am reminded of Pris Roos’ deep interest in locality and community. Walking from the Maashaven metro station, I pass by long rows of apartment buildings, a small shopping centre consisting of multiple supermarkets, a hair salon and a hardware store. This neighbourhood, called Tarwewijk, breathes a sense of community that I recognise from Roos’ works, which often depict similar scenes of daily life in bright colours using pastel, paint and collage on different supports such as large sheets of paper, canvas or cardboard. In her work Roos references city life, drawing on architectural signposts to guide the viewer through the story she attempts to share – narratives about how different communities around her interact with one another in the moment. Roos takes on the role of observer, inviting the audience to become part of the world depicted on her canvases as well. All elements of day-to-day life can act as inspiration for Roos’ work: from an exchange on the street between neighbours, to someone having their haircut, to protestors on the Erasmusbrug during the 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstration.

Roos Pris in her studio. Photo: Sanne Sanders.

The artist’s studio is located in a converted school building which also hosts many other creatives, as well as a children’s dance school. Although it’s one of the greyest and stormiest days a Dutch winter can offer, this building and the surrounding community presents itself as active and alive – children are playing in the schoolyard and the sound of their voices carry through to us as we begin our conversation about Roos’ entry into the art world. Walking into the studio, I feel welcome and accommodated: Roos pours tea, uncovers bowls of snacks and starts talking about her love of food, and how that love often functions as a starting point for her work. Roos is an interdisciplinary artist but is mostly recognised for her painting practice. She depicts people coming together in groups, but also paints portraits of the individuals that she crosses paths with.

Roos grew up in her parents’ toko (a supermarket that sells products from Asia, Africa, the Caribbean, North- and South-America, although toko can also refer to a small (take-away) restaurant where traditional Indonesian food is cooked) where she was heavily inspired by the local customers she encountered. The people, the smells and colours of the food, as well as the many conversations she experienced there; all came together to create an environment which Roos still draws upon as inspiration for her immersive installations and paintings. The artist also worked in the toko since she was fourteen years old, and still works there on Fridays and Saturdays. In the shop, Roos is constantly surrounded by what she refers to as ‘a family of neighbouring business owners’ and other locals. She discusses her experiences in the toko and how it has inspired her: ‘I acquired my determination to work from seeing my parents and how hard they worked in the store. Also, from a young age I saw them communicate a lot with different kinds of people; not only people from my own Indonesian background, but also other people, our neighbours for instance, or just people who come to get their groceries. For example, my neighbour in Alkmaar, where we had our first toko, came in everyday just to say hi and have a talk. She had Surinamese hair salon next door and became a sort of aunt for me.’

Roos Pris in her studio. Photo: Sanne Sanders.

Food, while appreciated and thought of differently across the world, can be seen as a common ground for people of all cultures. For Roos, this sense of universal recognition holds much value in her practice. Moving between cities and communities as a courier for her parents’ business, she entered and observed different worlds, using her parents’ products as point of entry. Roos: ‘I found a lot of joy in meeting different kinds of people, especially when I turned eighteen, got my driver’s licence, and had to do all the groceries for the toko for my parents, going to ‘De Centrale Markthallen’ (a wholesale food market in Amsterdam West) for instance, but driving to other cities as well.’ Roos’ ability to observe and gather stories from different city environments still remains at the core of her practice. When I ask her about the role observation plays in her art practice, she reflects: ‘Someone once told me that when they were looking at my paintings, it felt as if I, the painter, was part of the group that I portrayed. I really recognise that feeling actually. Part of what I enjoy when observing or talking to somebody I’m portraying is that I feel a strong connection to them; it really feels like we are both equals at that moment.’

Even though Roos didn’t enter the art world until she was in her late twenties, she was already intensely interested in comics as a child, illustrating her own as well. Roos: ‘Because my parents were always working, I was often by myself. My parents gave me a big desk where I would gather and read a lot of comics. Donald Duck for example, and also Franka, which is about a detective living in Amsterdam who helps museums by retrieving their stolen paintings. That was the first time that I came across somebody who went to a museum. But I didn’t go to a museum myself until I was twenty-five or something.’

As a child, Roos’ dream was to become a comic book illustrator. Roos: ‘My family didn’t really support that ambition. So, when I was about twelve years old, I stopped drawing altogether. It was only when I was finishing my degree in communication and multimedia design that I started drawing again, at the age of twenty-four.’ After completing her first degree, Roos reconnected to her love of illustration and drawing by creating mood boards for various advertising campaigns during her degree. After graduating however, when trying to enter the world of marketing, Roos experienced a lot of setbacks which prompted her to reconsider the work she was making. Roos explains: ‘After I had received my degree in communication and multimedia design, I was clueless on what to do next. I tried to get a job in the field of marketing, showing my portfolio to different advertisement companies, but soon realised I liked illustration much more than marketing. At the time, my portfolio consisted of autonomous drawing, leaving the companies to say I wasn’t the right fit for them. Soon I realised: this is not working.’

Looking back, this has been a major turning point in the artist’s career. Roos began to educate herself in ideas and discourses around contemporary art and art history, attending classes and reading different books. This was a decisive period for her; a moment in which she started to build her own visual language and expanded her sense of creativity. Reflecting on this period of personal growth and the transition into contemporary art, Roos says: ‘I read a lot of books, did a lot of self-study and joined a lot of workshops at the Volksuniversiteit, learning to make children’s books or silkscreen printing for example. Then one day, out of the blue, I was invited to join an exhibition in Lausanne in Switzerland. I had to pay a fee for it, but then again, I was really happy that someone wanted to show my work in the exhibition Drawing 2012 at Swiss Art Space in Switzerland. I thought: oh I can actually do this!’

For Roos, attending art school was still very much an abstract thought. It wasn’t until she visited a major postgraduate art residency in Amsterdam that the possibility of studying contemporary art at an academy presented itself to her. ‘I went to the open day of the Rijksakademie with my former partner and thought: this is amazing! To be able to do that with your life. It was quite coincidental that I ended up going to these open studios – my former partner grew up going to museums with her parents and I was invited to join them on their visits. That was only around the age of twenty-six. so quite a bit later in my adulthood.’ Yet although Roos’ path to study art was to some degree, serendipitous, it is not as though she just drifted into the field. The way she speaks about her journey tells me that she really chose, developed and forged her own path as an artist. Roos’ love for creating and drawing was strongly tied to her ongoing desire to connect to different people and communities, as a way to start to make sense of the world around her and through developing her practice further, these connections became increasingly clear.

Entering art school at the Royal Academy of Art (KABK) in The Hague, Roos felt excited to finally be immersed in surroundings which exemplified the contemporary art world. She started off making intricate illustrations in black and white lead pencil, but quickly saw the need to transform her work into a painting practice. Roos: ‘Entering the art academy, drawing was an obvious choice to me; I could always pick up a pencil and start doing it. But soon I discovered that it was through painting that I could really develop myself as an artist. I also made some more conceptual installations during my time at the art academy, but actually these still felt as portraits of people. I made an installation based on my hairdresser Jezus is mijn Kapper, for example, which I thought of as a sort of symbolic reference to the person itself. Those kinds of works really reflect upon my background and are at the heart of my practice.’

Whilst strongly informed by painting, Roos’ current work remains multidisciplinary, exploring drawing, collage, spoken word and installation. Her installations often consist of two-dimensional works installed on walls of an exhibition space, or of three-dimensional objects placed throughout the space, inviting the viewer to enter the dialogue physically. The immersive works provide visual cues with symbolic meanings and as a whole often work as ‘portraits’. Extending and questioning ideas of portraiture and identity has become a central motif in Roos’ practice. She uses a methodology and approach which is very accommodating for her subject’s story and narrative, which may include making rough sketches or videos, or recording interviews with her subject to watch back later.

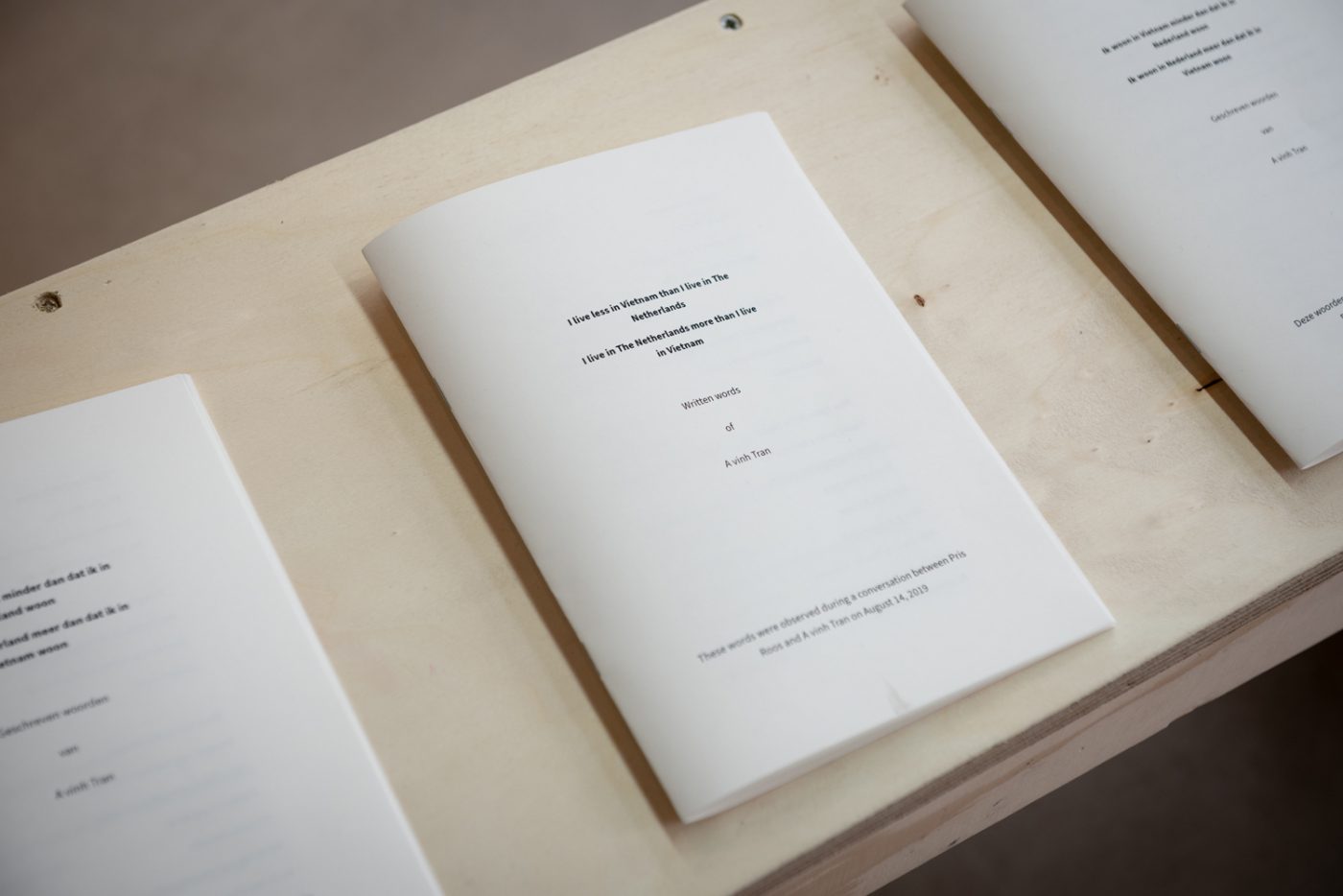

Roos Pris, I live less in Vietnam than in the Netherlands - I live in the Netherlands more than in Vietnam, 2020, in groupexhibition 'On Collective Care & Togetherness' curated by Leana Boven, hosted by Showroom MAMA. Photo: Lotte Stekelenburg.

Roos Pris, I live less in Vietnam than in the Netherlands - I live in the Netherlands more than in Vietnam, 2020, in groupexhibition 'On Collective Care & Togetherness' curated by Leana Boven, hosted by Showroom MAMA. Photo: Lotte Stekelenburg.

Roos Pris, I live less in Vietnam than in the Netherlands - I live in the Netherlands more than in Vietnam, 2020, in groupexhibition 'On Collective Care & Togetherness' curated by Leana Boven, hosted by Showroom MAMA. Photo: Lotte Stekelenburg.

An example of such an immersive work is Roos’ 2019 work I live less in Vietnam than I live in The Netherlands – I live in The Netherlands more than I live in Vietnam. Installed in 2020 during the group exhibition On Collective Care & Togetherness, curated by Leana Boven and hosted by showroom MAMA in Rotterdam; Roos’ work documents the story of A vinh Tran, a Chinese woman who fled Vietnam in the 1970s to the Netherlands. In this work Roos used large bags of different kinds of rice (which can also be found in her parent’s toko) to symbolise a bridge between her own world and the larger narrative of immigrant populations in the Netherlands. The bags of rice not only reflect the bodies and migrations of immigrants from all over the world to North-West Europe, but also the diversity of cultures which have rice as their basic food source. The bags stand side-by-side in a wooden boat-like structure, juxtaposed with the story of A vinh Tran recorded through a conversation with Roos and exhibited both as recording and transcript. In this work, Roos mixes personal stories with symbols that gesture to a broader societal discourse. Similar to the visual signs in her paintings, the objects in space act as visual signifiers.

During her studies at the Royal Academy (KABK) and later in Germany, and with the support of her teachers Femmy Otten, Dina Danish and Heike Kati Barath, Roos began to develop a visual language founded in portraiture and painting. It wasn’t until she went to study in Germany – as an exchange student in Bremen and later a master’s degree in Hamburg – however, that she really developed a more open, loose and immediate approach to the practice of painting. As the only painter in her year, she often felt weighed down by the emphasis teachers in the Netherlands placed on forming a more conceptually focused practice. Roos compares the German and Dutch approaches: ‘In Germany, I was put in a class called of thirty other painters. I noticed how they were much freer in their style of painting compared to what I was used to seeing around me. They really got the space to do what they wanted to do.’

Roos developed the brightly coloured works which she is known for today via the same methodologies she learnt whilst studying in Germany. Reflecting on one of her installations involving recordings and observations of her subject in their home or in public, Roos indicates that for her: ‘it’s really a way of embodiment.’ She continues: ‘I find it very important to pay respect to the person I portray, and to the specific situation and environment this person finds themselves in. This way, viewers can really be immersed into the painting. I hope that people can really become part of that gathering, or moment, or story that is depicted on the canvas.’

Of course, this all links back to Roos’ skill as an observer, her ability to collect stories of the people around her that she fostered ever since she was a child. Today, it is no longer her parents’ toko that acts as her main meeting place, but it is her canvases that perform as a platform where communities intermingle. Happenings of everyday life are depicted, giving form to what is in fact intangible – a sense of community. Roos: ‘To me, paintings are not just visual images; they carry a lot of meaning. When I see a portrait I’ve made, I see that person again and I relive that whole experience of meeting and talking to this person. And often, the person is living just around the corner from me! That’s what makes it special, I think.’

‘I find it very important to pay respect to the person I portray, and to the specific situation and environment this person finds themselves in.’

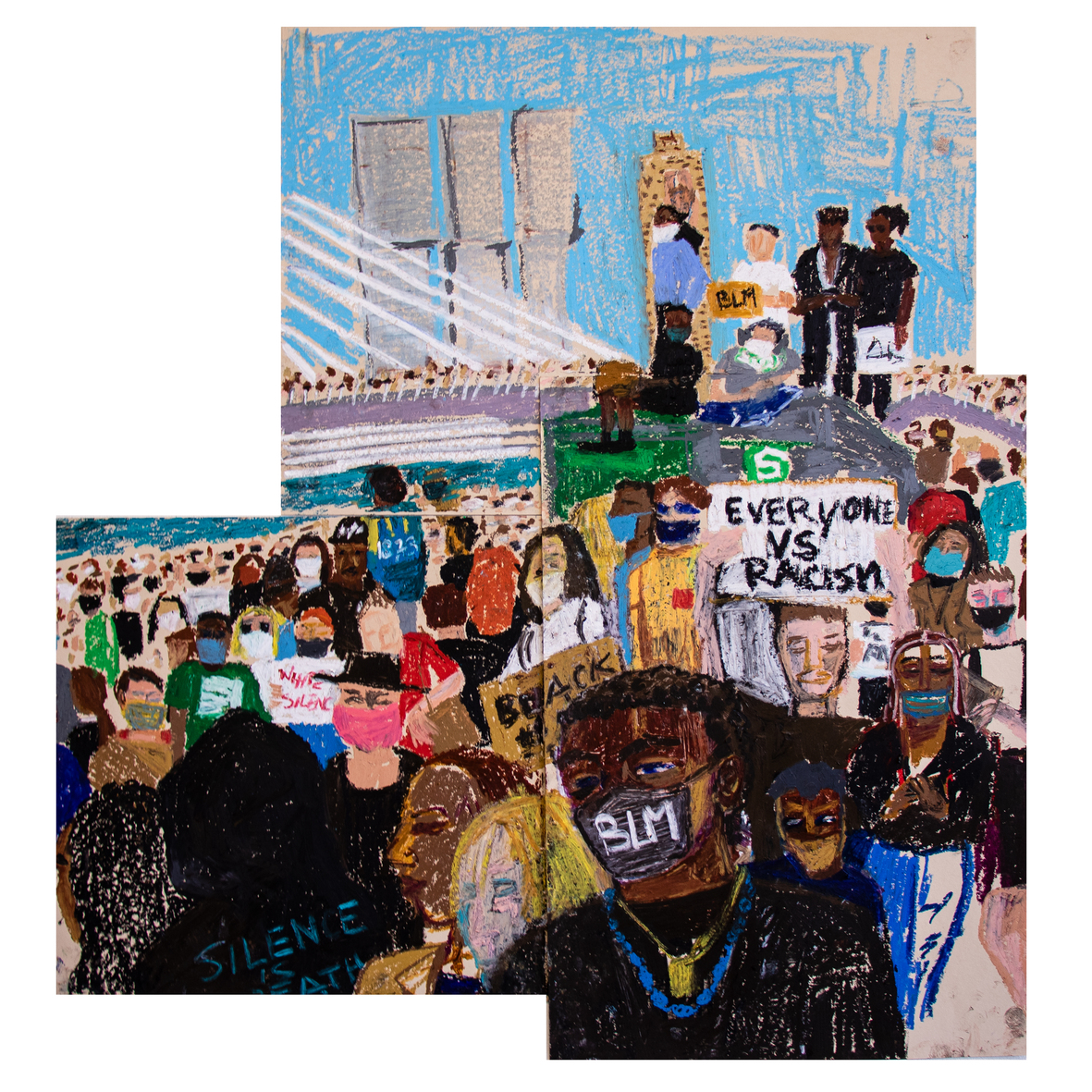

Roos Pris, 3 juni - Erasmusbrug Black Lives Matter, 2020, oilpastel on paper.

Over the last two years, Roos has participated in a number of group shows and projects and also had her first solo show at Hama Gallery in Amsterdam. In late 2020, Roos was chosen by CBK Rotterdam and the City Archive as one of the three ‘stadstekenaars’ [city sketchers] a role for which she reflected on the city of Rotterdam during lockdown. The other two stadstekenaars were Erico Smit and Frank Stoks. The resulting work culminated in to her first museum exhibition Getekend: Rotterdam! De Stad in lockdown at Kunsthal, curated by Shehera Grot. One of the works Roos made during this time was 3 Juni -Black Lives Matter-protest bij de Erasmusbrug (2020); a very prolific oil pastel work on paper that captures protestors coming together in solidarity. The city was divided during this historical moment, confronted with tensions brewing both because of Black Lives Matter protests, but also because of the global pandemic. This meant it was a very engaging time to be involved in a project from a position which was about recording daily life in Rotterdam.

Although making drawings during the protests themselves was a significant experience for the artist, Roos felt that the work she made as a response to an event she witnessed in the weeks after the protest really affected her the most. Acting as a starting point for her work, I See I See I See I See Daily Paper, Clan de Banlieue, Sumibu and Concrete Blossom in Rotterdam-West (2021), Roos was invited to listen in on a conversation and coming together between initiators of black owned fashion labels such as Abderr Trabsini, Richard Lopes Mendes and Jordan Soediono to discuss the success of their businesses and projects. For Roos, it really represented a key moment and parallel between success and endurance to thrive in a time of social upheaval: ‘they were just talking about hip-hop and fashion and telling each other how they had succeeded as owners of black owned businesses. I found that inspiring.’

‘Just like anyone who is lucky enough to be in exhibitions or to make a living of their work, should give back to the community and the city.’

Installation photo from the group project 'A Funeral for Street Culture' by Metro54 and Rita Ouédraogo hosted by Framer Framed, Amsterdam (2021). © Eva Broekema / Framer Framed.

Installation photo from the group project 'A Funeral for Street Culture' by Metro54 and Rita Ouédraogo hosted by Framer Framed, Amsterdam (2021). © Eva Broekema / Framer Framed.

Installation photo from the group project 'A Funeral for Street Culture' by Metro54 and Rita Ouédraogo hosted by Framer Framed, Amsterdam (2021). © Eva Broekema / Framer Framed.

Reflecting on and capturing this moment where this small group came together to share their achievements and connect to the city, exemplified something important to Roos. She reflects: ‘I found that image, on West-Kruiskade in the square – where there was a lot of noise from the city, and the passers-by – but I found that image interesting, the layer on layer on layer, I found it interesting to show as an installation in Amsterdam.’ Roos showed this work as a large panel installation during the group exhibition A Funeral for Street Culture by Metro54 and curator Rita Ouédraoago hosted at Framer Framed. For Roos, I See I See I See I See Daily Paper, Clan de Banlieue, Sumibu and Concrete Blossom in Rotterdam-West (2021), represents a profound intersection of research, ideas and people, paving new ways of reflecting community and the faces involved in that effort. Roos relays why this experience touched her so much: ‘My function most of the time is just to observe and listen to people. And although in this work we can’t hear the conversation itself in exact words, the depiction of people coming together is, I think, the most important subject matter. Just like there were a lot of people, both of colour and white, coming together on the Erasmusbrug, sharing an important movement for justice, this new work also shows people gathering together.” In the exhibition, the large panel painting was supported by a wire fence; an experiment which Roos worked out in collaboration with the spatial designers Setareh Noorani and Jelmer Teunissen. Roos often works using found materials like cardboard boxes and other things she finds in the neighbourhood, creating a stage for her work, and playing with the boundary between institutions and public spaces.

Roos investigates, observes and listens to the stories around her in the city that she calls home. From Alkmaar to Amsterdam to The Hague, Bremen, Hamburg and now in Rotterdam, she reflects on these spaces and communities through her paintings and installations with sensitivity and an eye for detail. With its immediate gestures, mixture of layers and combination of different found materials, Roos’ visual language is easily recognisable. When reflecting on what painting has come to mean for her and the wider context of the medium in recent years, Roos says: ‘a lot of my friends who are also painters reflect on their own environment, not just on their local city-environments but also on what is happening in their communities. Their way of painting is quite fast, just like mine. If I compare this approach with that of painters in art history, I recognise a difference; back then, paintings took a lot of time, and had a lot of layers. Today, we just want to portray and show what we see as soon as possible.’ The sense of urgency that is unfolding around us, during such a tumultuous time in history, demands a kind of immediacy of artists, one that Roos has found in painting and installation.

Talking to Roos in her studio, she seems to lead a balanced life, dividing her time between working in her studio and working at her parents’ toko where she immerses herself in different worlds. When it comes to the communities she depicts and the stories she gathers, Roos really wants to open doors for young people like her, and feels the responsibility of her position: ‘I have quite an outspoken voice through my work, but I strongly believe that I, just like anyone who is lucky enough to be in exhibitions or to make a living of their work, should give back to the community and the city. As a woman, and moreover as a queer woman of colour, I feel the urge to help others as well.’

Pris Roos will show new work in the group exhibition The Kids are Alright pt.II curated and presented by The Constant Now & Please Add Color in Antwerp, Belgium, from 12.1 – 30.1.2022.

Pris Roos is represented by Hama Gallery in Amsterdam.

Alyxandra Westwood

is an artist, writer and curator and is based between Utrecht and Melbourne