Rechts installatie MEGALITH van Marit Westerhuis in het Groninger Museum, links de actie van Fossil Free Culture NL tijdens de opening van de tentoonstelling

Disrupting the fairytale of technological progress – Marit Westerhuis’ fight against the sponsors of the Groninger Museum

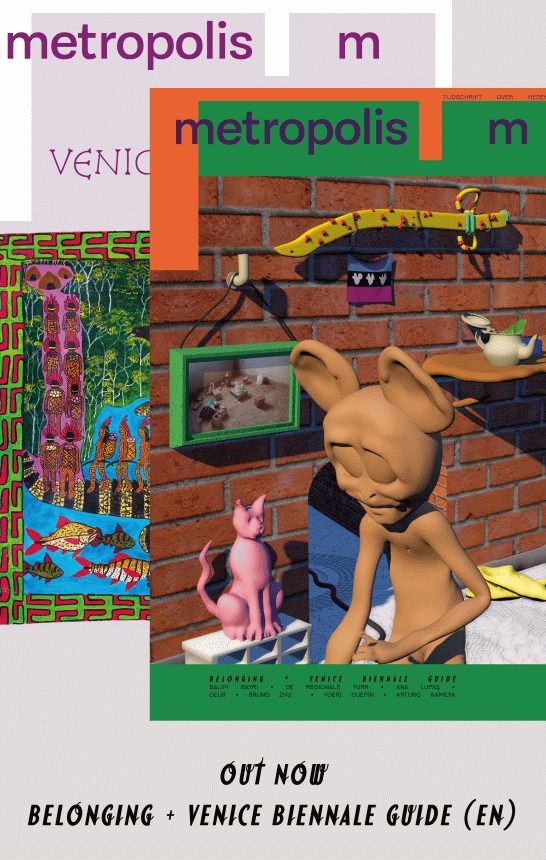

The opening of Marit Westerhuis’ post-apocalyptic installation MEGALITH at the Groninger Museum included an unannounced protest action by Fossil Free Culture NL adressing the fossil fueled sponsorships of the museum. Maia Padura talks to the artist and museum director Andreas Blühm about the surprise act and the exhibition. Will it bring a change of museum policy?

“There is no room for ‘transition fuels.’ The only transition we will make then is to the post-apocalyptic world as the one that is now installed in front of you.” Marit Westerhuis points the audience towards her exhibited installation MEGALITH – one that is opening tonight and that she believes will resemble the future if we continue going on like this. The crowd, consisting of the crème de la crème of the Groningen art world, listens patiently. When Marit adds that “it is time to address the elephant in the room”, her words are answered by a heavy silence: the calm before the storm.

Mysterious figures wearing Venetian style white masks enter the space and step into the hilly landscape of vivacious grass and petrol cans wrapped in black plastic. The ghostlike figures slowly walk backwards while from behind their masks a green liquid starts dripping on their white shirts. The performance is inspired by the fortune tellers and soothsayers that occupy Dante’s 8th circle of hell in the Divine Comedy. The performers are the foreseers of the climate crisis’ consequences, punished to look ahead while moving backwards.

Marit continues her speech: “The museum, that you are standing in right now, is sponsored by key players in the Dutch fossil industry: GasUnie and GasTerra.” Her voice trembles with emotion: “As an artist from Groningen, I think it is important to warn the Groninger Museum not to believe in the fairytale of technological progress as salvation.” A mixture of panic and confusion starts to spread like a wildfire; the museum employees and representatives become visibly uncomfortable, but don’t interrupt the performance. Marit wraps up her speech in one breath: “We live in mythical times- let’s act accordingly.” The performers slowly and silently leave the room. The audience thought all was part of the opening act but the museum staff was completely surprised. When I meet Marit to talk about the performance two days later, she tells me that the museum responded to the performance by giving her the silent treatment.

Marit was selected as one of three artists to participate in the third edition of the Young Grunn Artist: a one-year trajectory for local artists led by Groninger Museum and NP3 to further their artistic career. She was invited to present her work in a special solo exhibition at Groninger Museum. MEGALITH was the result; preparing for it took over than a year.

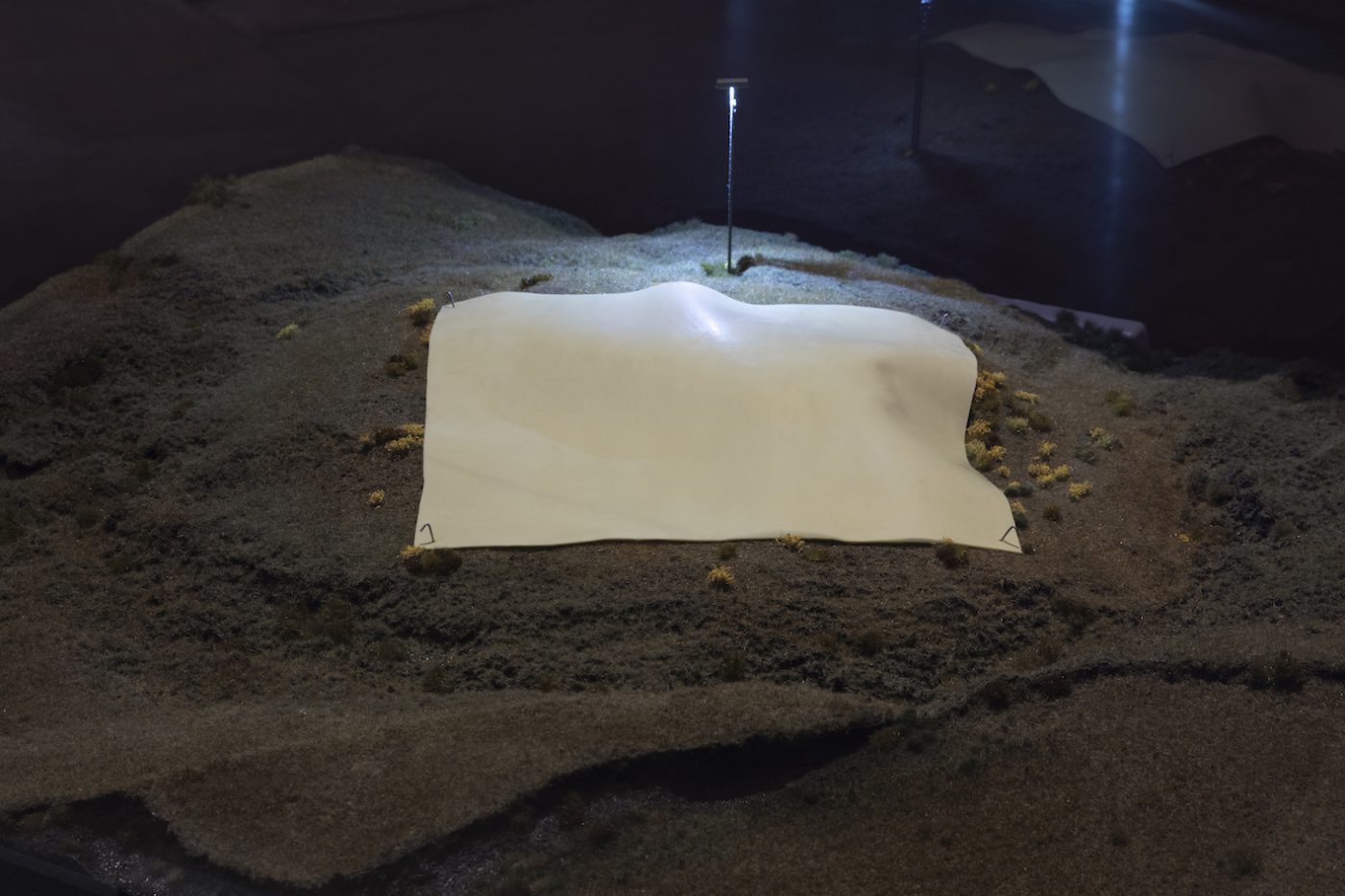

Marit: “I see these big tech-companies as creating a new, contemporary mythology. We really seem to put our faith in people like Elon Musk; they are the wizards of our time. But I think it is quite dangerous to put your faith into technocrats.” With her exhibition, Marit questions our belief in technology as a positive solution to our current climate crisis. A completely macabre world, one in which we have lost sensitivity to nature completely and have created an artificial landscape of waste materials instead, seems to be a more likely result of such technological interventions. Still, MEGALITH offers some hope. It represents “a world where humans abandoned the belief that technology will save us and have instead started to perform rituals inspired by Norse mythology. MEGALITH is the last resort that allows humans to talk to the gods of nature.”

[blockquote]MEGALITH represents “a world where humans abandoned the belief that technology will save us”

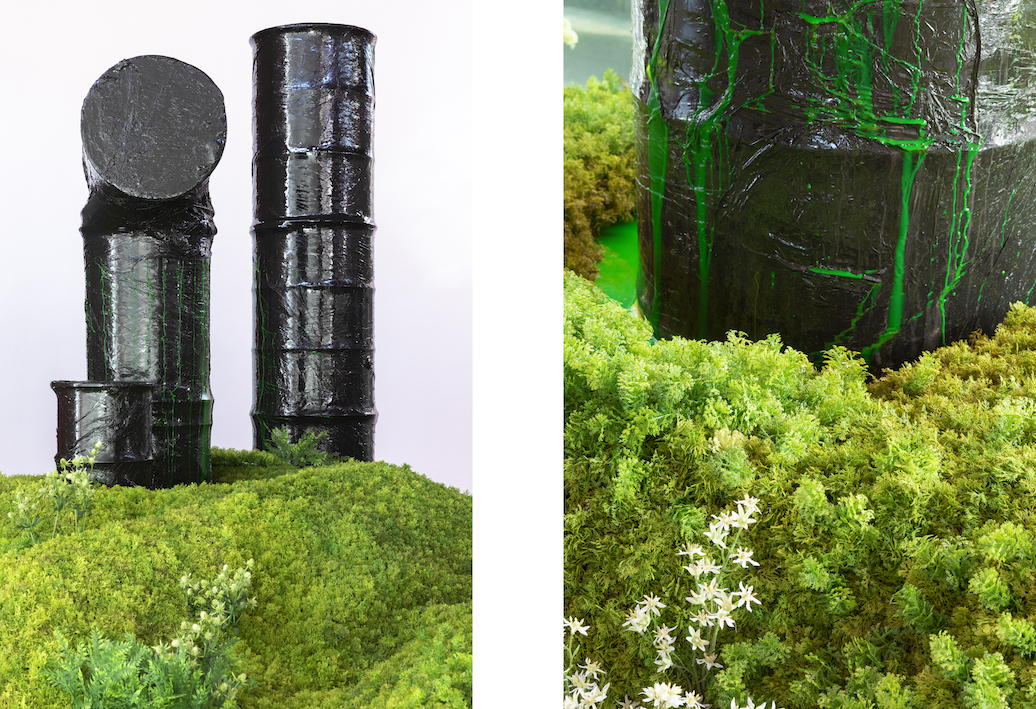

Marit Westerhuis, 'MEGALITH', Groninger Museum, photo: Heinz Aebi

Marit Westerhuis, 'MEGALITH', Groninger Museum, photo: Heinz Aebi

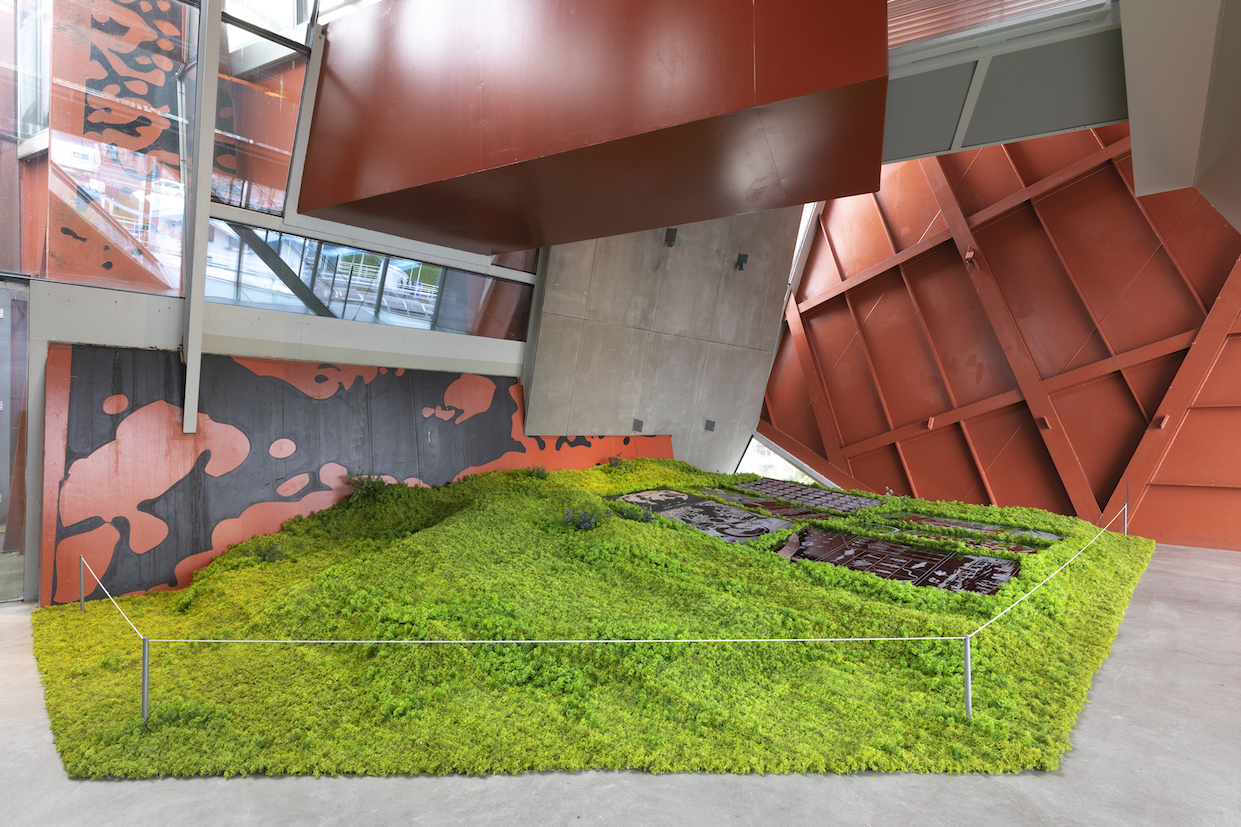

Marit Westerhuis, 'MEGALITH', Groninger Museum, photo: Heinz Aebi

The exhibition title “MEGALITH” refers to the prehistoric stones, a recurring theme in Marit’s work. Here, the megalith forms the “post-apocalyptic” scene for the future of humanity. The green landscape is filled with plastic herbs that look and smell like humid moss. On the grass carpet, futuristic structures stand in a semi-circle, reminiscent of the primitive stones. Upon a closer look, they turn out to be petrol cans, covered with running water that has a toxic and futuristic neon green color.

Pitch-black glass cubes are installed on the left side of the installation. The boxes, Marit explains, can be seen as “time capsules into alternative realities. They are inspired by the 9th circle of hell in Dante’s Divine Comedy. Each capsule represents a world worser than the previous one. Most ot them are inspired by pre-historic times, three of them are more industrial looking.” On a stone passage that seems to be inspired by Drenthe’s ‘hunebedden’ is written in graffiti: “Abandon all hope, you who enter here.” The quote is taken from the message inscribed in Dante’s gate of hell. Here, just like the exhibition itself, it serves as a warning.

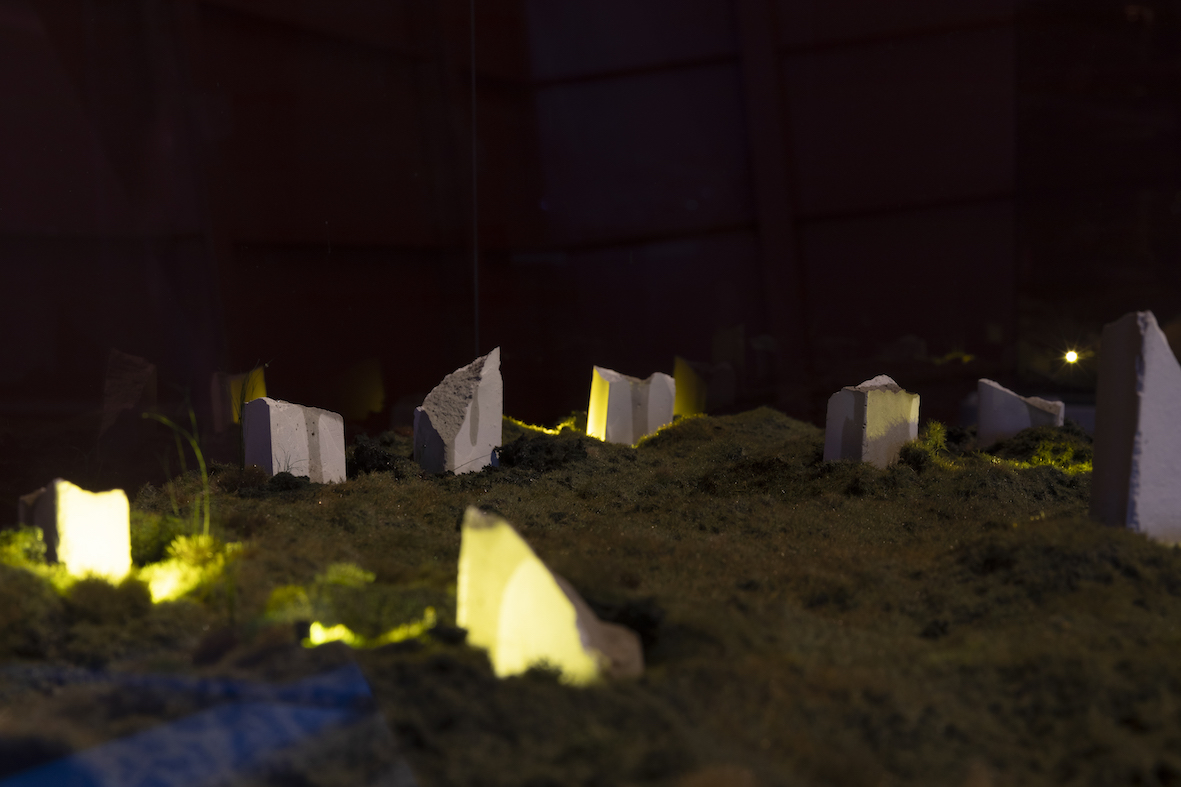

Further down the exhibition, glossy black rectangular panels are installed in the same green landscape, resembling tombs in a graveyard. Marit: “They are inspired by rune stones but I call them gravestones. In Scandinavia you have these stones with wounds (inscriptions) in it that explain what happened somewhere. I wondered: ‘How do you tell future people about the climate crisis taking place here and now? Do you write something in English or do you try to symbolize it using hierogliefs?” Marit opted for the second method, telling the story of our future world through anarchist symbols. Some resemble logos of fossil companies, others the permafrost holes in the earth. One depicts the mask-balaclava that symbolizes the artist’s protest, and yet another represents an old Ragnarök symbol from the North mythology that announces the end of times.

On a stone passage that seems to be inspired by Drenthe’s ‘hunebedden’ is written in graffiti: “Abandon all hope, you who enter here” – just like the exhibition itself, it serves as a warning

Marit Westerhuis, 'MEGALITH', Groninger Museum, photo: Heinz Aebi

Marit Westerhuis, 'MEGALITH', Groninger Museum, photo: Heinz Aebi

Marit Westerhuis, 'MEGALITH', Groninger Museum, photo: Heinz Aebi

Having discussed the installation on view, I ask Marit to tell me a bit more about her critical opening performance, the debate that followed up on it and the events that preceded it. Considering that the fact that both GasUnie and GasTerra sponsor Groninger Museum is quite well-known, Marit regrets not having investigated this sponsorship more before agreeing to exhibit. Walking through her exhibition, Marit softly tells me: “I didn’t realise how big these gas companies’ role was in the museum, until I saw a design proposal of the exhibition poster. Afterwards, I had sleepless nights, weekends even, because I thought this whole exhibition was going to collapse. As an artist, I feel that I had to take a position, especially considering the fact that my work directly addresses the climate crisis and the role of big gas companies in it.”

Marit explains having been faced with a dilemma: should she step out of the project completely or use the museum’s platform to tell her message? She decided to go for the latter: “I thought: I can just be idealistic about all this and drop out, my message remaining invisible, or I can continue with the exhibition and make a public statement. As an insider, as ‘their’ artist, I decided to stand up against their policy, using the exhibition as my Trojan horse.” Marit explains having grown up in Groningen near the earthquake region; not addressing the issue of sponsorships seemed simply too hypocritical to her. She started collaborating with Fossil Free Culture NL just a couple of weeks prior to the opening of her exhibition, resulting in the performance described earlier.

During the preparations of the exhibition, when Marit became concerned about the presence of the logos of the two gas companies on the poster of her exhibition, the museum and she started to negotiate. In the end, Groninger Museum didn’t agree to remove the logos of the sponsors from her poster. However, they settled down a compromise of separating the sponsors of the museum, including the two gas companies, in one corner of the poster from her sponsorship. Still, the agreement didn’t put her worries to rest, leaving her to still organize the critical performance.

“As an insider, as ‘their’ artist, I decided to stand up against their policy, using the exhibition as my Trojan horse”

Marit Westerhuis, 'MEGALITH', Groninger Museum, photo: Heinz Aebi

Marit Westerhuis, 'MEGALITH', Groninger Museum, photo: Heinz Aebi

Marit Westerhuis, 'MEGALITH', Groninger Museum, photo: Heinz Aebi

When I speak to director of Groninger Museum Andreas Blühm, he explains: “We are aware of the issue. We are aware of FFCNL’s campaign. We would be happy to talk to them about it. The sponsorship is no secret; it’s all over the museum. Nobody denies it. Everybody sympathizes with the ideal of fossil free energy.” He regrets that the museum wasn’t given the option to formulate an answer to the performance: “We would like to be a forum for debate.”

He explains: “We organized the opening, and were confronted with uninvited guests who started to walk on the artwork –which you are not supposed to do– and presented a performance. This was not part of our intended project: Marit invited them to do that without telling us. So, I don’t even want to give a comment on the artistic quality of the perfomance.” The performance, as well as Marit’s emotional words, bewildered the museum’s employees, who were all intrigued by Marit’s installation: “We are happy with the result and that Marit won the award.”

The performance didn’t shake their thoughts on the sponsorship. No changes nor conciliations of contract with the gas companies are expected in the policy of the museum: “We don’t like to be dependent on fossil fuels. I mean, nobody does. But as long as we do, we work with them. In our opinion, it’s good if there’s at least a tiny little part of these companies’ profit that can be used for cultural, sports or social initiatives. So, I think it is counterproductive not to work with them and it’s actually doing harm to the good cause. If you want to get rid of fossil fuel as a source of energy, you have to work with them.”

MEGALITH is on view until the 30th of October, at Groninger Museum

Maia Paduraru

studies journalism at the University of Groningen