Ibrahim Mahama, ‘Garden of Scars’, Oude Kerk. Photo: Mike Bink

“I’m interested in the brutality of history as a seat for a new point of thinking” – talking to Ibrahim Mahama about “Garden of Scars”

When you first set eyes upon Ibrahim Mahama’s exhibition at the Oude Kerk, the idea of a “garden” may not be at the front of your mind. A graveyard would be more apt. Inspired by the history of both slave traders and enslaved peoples, concrete and rubber moulds of gravestones sit heavily, symbolic of death and decay. Still, there is a surprising warmth to Mahama’s project. Evie Evans asks the artist about the exhibition and the restoration of memory it sets out to perform.

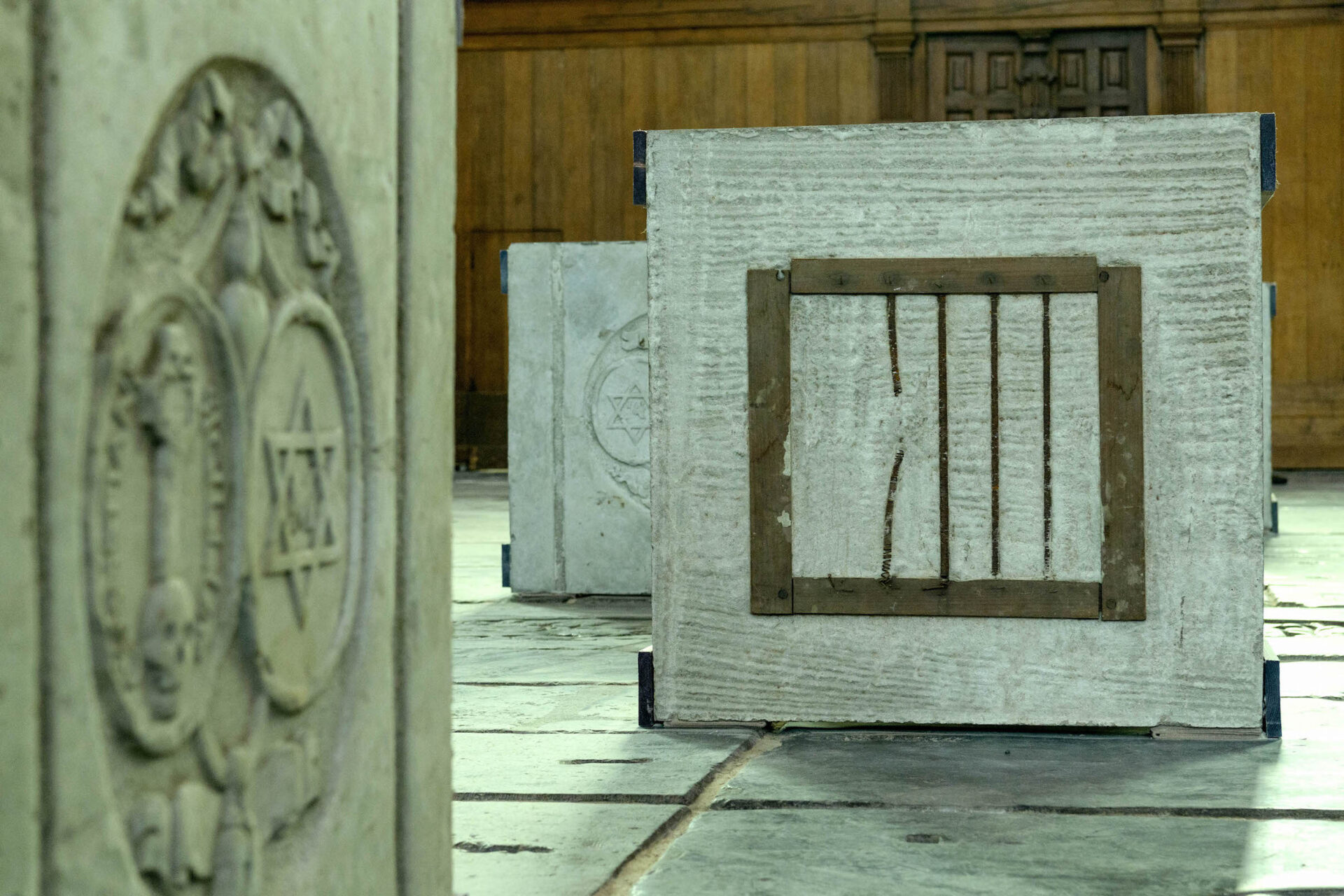

There is something haunting about the concrete sculptures on display at the Oude Kerk. Casts of gravestones from both Amsterdam and Mahama’s hometown of Tamale in Ghana stand upright, out of the terrain. Remnants of other objects, wooden furniture and metal lamps, emerge from the sides of the concrete; other components of the sculptures lie hidden in between the void of the harsh slabs. “I’m interested in the brutality of history”, he explains, “and how we can use that as a seat for a new point of thinking.” That is a notion that becomes evident to me in the face of, and the weight of, his sculptures.

Ibrahim Mahama, 'Garden of Scars', Oude Kerk. Photo: Mike Bink

The main sculptures occupying the space are made from casts of graves in the Oude Kerk and a Russian Cemetery in Tamale. Even the casts taken from the Oude Kerk have been re-purposed and displaced from their original location. A stark white grave from Ghana and its large cross seem simultaneously appropriate to the location and out of place. But it’s the floor of the Oude Kerk that drew Mahama in the most. The floor exists entirely of gravestones, which, after years of erosion, have turned into smooth surfaces, sparking Mahama’s interest in the marks of history and memory.

The Oude Kerk’s floor exists entirely of gravestones, which, after years of erosion, have turned into smooth surfaces, sparking Mahama’s interest in the marks of history and memory

Ibrahim Mahama, 'Garden of Scars', Oude Kerk. Photo: Mike Bink

“A gravestone is like a scar on your skin; it takes your mind back to a specific moment in time. It’s like a teleportation device in a way. Although it might often look ugly, I also find a certain sense of beauty in how it allows our minds to travel and access different points of memory.” Apart from the concrete casts, rubber moulds were made of stones from Ussher Fort in Jamestown, Ghana, a former Dutch fort and prison. They appear fused into the ground, easily stepped over like any other gravestone in the church. At times they are draped over the concrete sculptures; an uncomfortable contrast between the heavy forms and their weighted colonial history.

Mahama’s idea of this “garden” was to tie the forms and history of his work together. The inspiration for the exhibition came not only from the site of the Oude Kerk itself, but also from an ongoing project Mahama is carrying out in Tamale. Alongside the artistic and cultural platform he initiated in the city, The Savannah Centre for Contemporary Art (SCCA), Mahama also acquired a silo in Tamale: an abandoned brutalist building built in the mid-twentieth century by Russian and Polish architects for food storage. Buildings like these were constructed at the behest of the first president Kwame Nkrumah, but abandoned at various stages of their development after his coup, a vestige of the pressure Ghana faced during the Cold War. This particular building in Tamale never made it past its foundation, a deep basement and a single level. It was closed off by the city, filled with heaping sand and dirt, flooded with rainfall and debris. Over time, the soil was transformed and created its own ecosystem – a home to birds, snakes, and bats. For Mahama, it was “a pedestal for things to happen.”

“And I thought, why not excavate what is underneath the building and then put it on top of the building and transform it into a garden?” In his mind, the debt and decay within the building represented a “seed of potential for transforming what the building was and what the building could be.” He created a garden on top of the silo to grow food for the new wildlife and create a space for local people. Something he had already been doing at his studio The Parliament of Ghosts. “I was very much interested in this idea of what the garden could be.” However, the bats became the “chief protagonists” of the silo, taking ownership of the building.

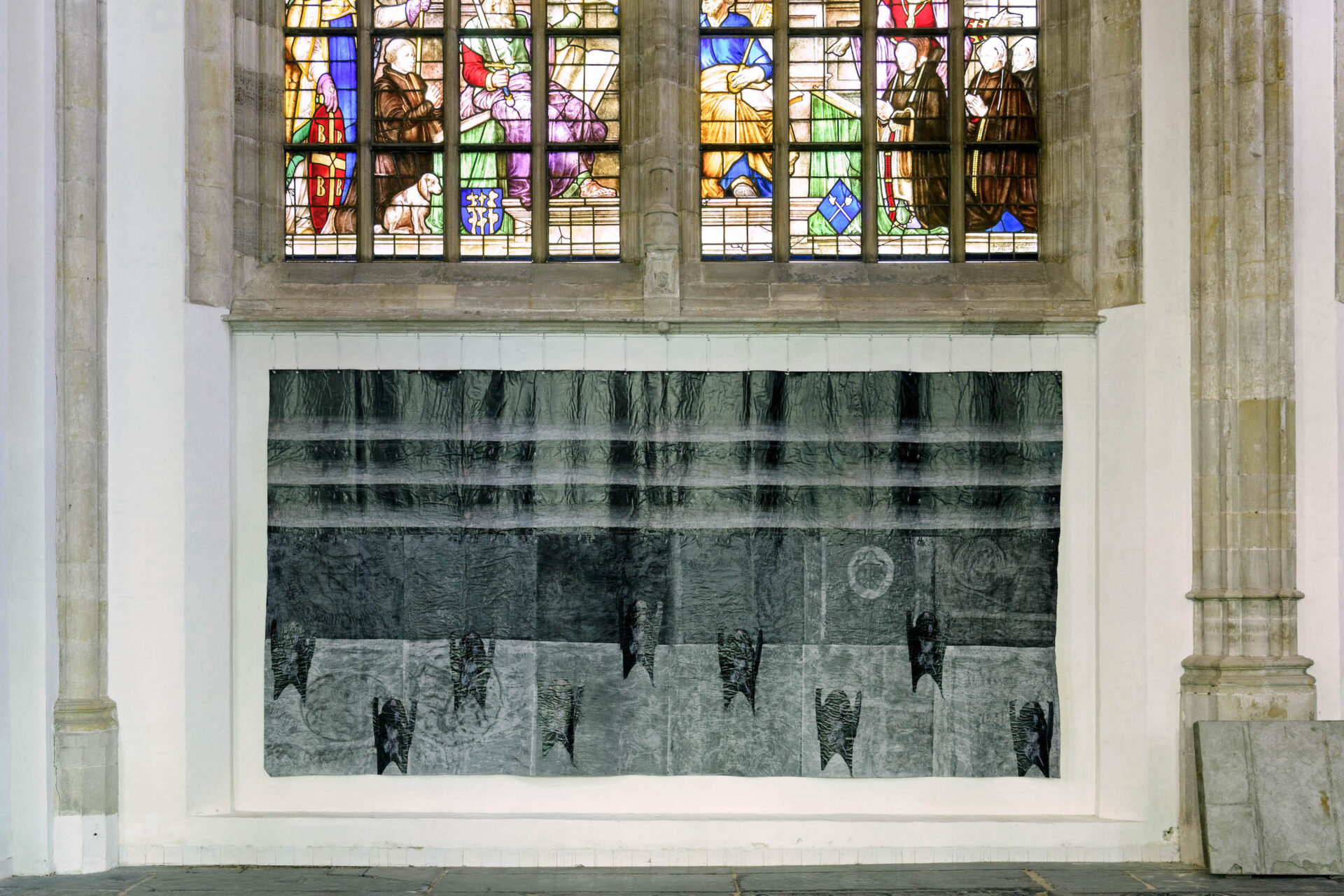

Ibrahim Mahama, 'Garden of Scars', Oude Kerk. Photo: Mike Bink

That began to explain the bats hanging from the vacant ceilings of the Oude Kerk. Their forms are a little unclear, dots of black against the stone and wood of the church in an almost comical overtaking of the space. They are a recurring motif, materialising from the shadows of his large-scale drawings and taking centre stage in one of five sound pieces. The audio installation plays overlapping tracks, such as the twittering of the wildlife in the silo, the sound of labourers working on the sculptures, and a teacher instructing a class in a classroom built from another one of Mahama’s installations. The sounds play in the middle of the cold church, drawing you across the floor, weaving between the sculptures into the heart of the space.

Mahama explains that further into the process, the exhibition came from “the simple idea of evacuating”

Ibrahim Mahama, 'Garden of Scars', Oude Kerk. Photo: Mike Bink

Mahama explains that further into the process, the exhibition came from “the simple idea of evacuating.” The site of the church itself, he mentions, has been transformed over the course of so many years – most of the bodies previously buried there have been moved. Mahama carried the idea of the heritage site back to Ghana with him. “When we were excavating the silo, I was mainly also thinking about it within this kind of archaeological sense.” Even in the Oude Kerk, the concrete sculptures resting against the back wall of the church would be at home in an archaeological site or ruins of an ancient civilization.

Thus the process unravelled into something much more complicated and labour intensive. In a smaller side room of the church, the exhibition continues with a short film showcasing the labour-intensive process of making the sculptures in Tamale. Drone footage of Mahama’s studio in Tamale, the brown dirt in contrast with the lush green grass, dirt paths cutting through the lush like a gash. A change in the landscape. Sometimes in silence, sometimes with only the sound of the workers heaving wet cement, their carts barrelling along the carved out path to deliver more material, the bats trilling in the background. The process of silicon moulding is mirrored in Amsterdam and Tamale.

The video reveals just how much labour went into the entire exhibition. Moulds of the Oude Kerk gravestones were made in Amsterdam and shipped over to Tamale. Others were made in Jamestown and Accra and sent to Mahama’s studio where a large team set about making the concrete sculptures as if they were intended for building materials, before everything was sent back to the Netherlands. Not to mention the drawings and film itself. Mahama himself admits: “It was literally one of the most difficult works I had done. And not just difficult in terms of the physicality, but in terms of the realisation; I could not even imagine how it would be.” An archaeological dig is no easy undertaking, but it often uncovers more than just structures. The smallest, everyday objects can tell us just as much about a particular history.

Ibrahim Mahama, 'Garden of Scars', Oude Kerk. Photo: Mike Bink

Ibrahim Mahama, 'Garden of Scars', Oude Kerk. Photo: Mike Bink

The same can be said for the remnants of roof tiles taken from Dutch forts in Ghana. Placed on the floor amongst the larger sculptures in the exhibition, their dusty copper colour is prominent amongst all the grey, though they are well hidden. In his work, Mahama repeatedly uses found objects, collected from villages and people in Ghana. Why these ordinary things? “It’s the memory within these [objects],” Mahama asserts. We discuss how they can be transported across the world, into many hands and for many uses. These are personal, everyday objects, symbols of home that are also evocative of a global colonial history. For example, broken parts of chairs sit stuck in the cement. “These are old British colonial chairs that were made in Ghana in the 20th century,” Mahama explains, showing photos of his collection in the Parliament of Ghosts. “When you had this chair in your house, it meant that you were a very big man, and it was only the father that sat in this.” Recalling the notions of scars again, Mahama explains, “it’s almost as if we begin to transfer our lives or our bodies into these materials”.

However, for Mahama it’s not just the memory of the objects he collects but also what the site of collection or presentation represents. That becomes clear in the site-specificity of the exhibition and just how well the works have been created for the space. Take the bats, for example, or even the colour of the block sculptures. The works are so well crafted for the space, in fact, that I almost missed the higher drawings created in the exact shape of the church’s pointed arches. Straining to look up, it’s hard to tell what the image or material actually is. Mahama clarifies: “These ones are collages, they are drawings inspired by photographs that I made of the bats in the space in Ghana which I cut out and pieced together. In the background appears the floor of the church that we invited the audience to make a frottage of.” All the elements of the exhibition fuse together with each other and the site as if they have always been there.

Garden of Scars is, perhaps, brutal in the sense of unembellished; what you see is what you get

Despite Mahama’s interest in the “brutality of history” – whether that may be visually or thematically through the violent history of colonialism – there is a profound contrast between the brutalist and cold forms of the artworks and the surprising warmth of the project. The site-specificity of the exhibition creates a bewitching unity with the artworks and the history of the space. Garden of Scars is, perhaps, brutal in the sense of unembellished; what you see is what you get. As Mahama clarified for me, “The artist is just meant to create a work that is made up of a constellation of ideas and forms. And people can read their own meanings in it.” What I find particularly striking is Mahama’s decision not just to cast individual gravestones, but also the cracks in-between. His sculptures show the joining of stones, their demarcations and imperfections.

Mahama’s “new point of thinking”, therefore, is one of the in-between: what lies within the gaps? One only has to look in the spaces of his sculptures, the space between Ghana or the Netherlands, or the expense of the Oude Kerk, to see all the hidden details of its material history. Mahama’s thread of repatriation also becomes disjointed, patched together. What we see here is not repatriation in the sense of a full restoration of objects. Rather, we witness a restoration of memory; partial and fragmented like the motifs of the show. Mahama offers us something remarkably intimate; little pieces, remnants, ruins and new ideas from his studio in Ghana have been made at home here in the Oude Kerk. A new form materialises when we focus on the fractures between the frames. In a graveyard, a garden can grow.

Ibrahim Mahama’s exhibition Garden of Scars is on view at Oude Kerk until the 19th of March

Evie Evans

is a writer and researcher working around how coloniality occupies our past, present and future