David and Googliath

Last weekend the Trouw Building in Amsterdam served as the venue for a conference called ‘The Society of the Query’ (SotQ) subtitled ‘Stop Searching, Start Questioning!’ organised by Geert Lovink’s Institute for Network Cultures. The two day conference proposed to instigate a critical debate, not just about the way we use search engines, but also about the way they use us and – ironically – took place in the space which just a decade ago housed the printing presses of all major Dutch newspapers. Although the title smartly refrains from using the ‘G-word’, a quick flick through the program leaflet instantly made clear which way the guns were pointing. The gathered techno-elite made no qualms about their critical stance towards the world’s biggest information middleman.

Differences in background of those present, both speakers and public, quickly dissolved because of the omnipresence of it’s elected adversary. PHD researchers, cultural historians/analysts, new media specialists and artists, all shared in the goal of critically assessing Google’s prowess, looking not at the upside (the opening up of the world so to speak), but mostly at the downside: Google’s position as an information monopolist and the effect this has on us – Google users.

The imagery of the benevolent big brother, or – as Neural.it editor and one of the creators of the net.art work Google Will Eat Itself (GWEI) – Alessandro Ludovico poignantly described it: ‘the funny dictator’ was very present. Ludovico presented Google as a company which unremittingly entertains us into using its growing array of services, posturing as a public service, while it effectively only has one aim: making a profit by monetizing and privatizing information we generally still think of as ‘public’ or ‘communal’. However, as Ludovico found out, the fun and ‘open’ way in which Google presents itself to the outside world quickly turns out to be opaque and threatening when you start using their services against them, even if it is ‘only’ for an artwork. Using the motto let’s share their shares’ GWEI started as a hack, which used Google’s Adsense to generate a cash flow to a Swiss bank account that automatically bought a share in Google whenever possible. Although calculations showed that it would take 23 million years to gain a controlling interest in Google this way, Google shut the account down and sent a cease and desist order. Even a number of – untraceable – threats were made through Skype.

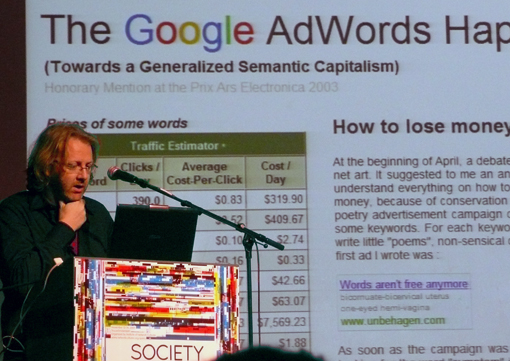

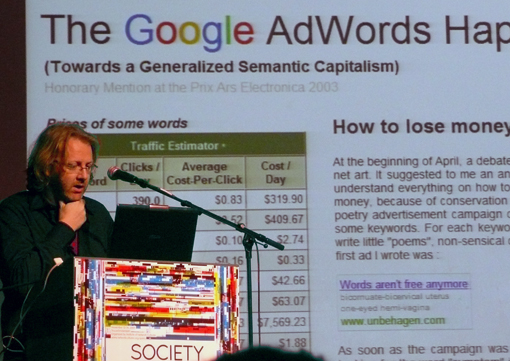

A similar story – if less saucy and with different aims – came from French artist Christophe Bruno, who used Adwords to publish short poems like:

mary !!!

I love you

come back

john

or

don’t ever do that again

aaargh !

are you mad ?

ooops !!!

on Google’s search result pages. His aim: to subvert the semantic nature of search by inserting cultural capital into an economically structured environment. Google’s adwords monitor reacted immediately: within 24 hours he was warned several times and eventually kicked out of the service because his adverts weren’t ‘effective’ enough. Censored on economic grounds, who would have thought? What Bruno found most intriguing though was Google’s success in creating a ‘semantic capitalism’, turning language itself into an economically viable raw material. Through Adwords and Adsense every word used has a monetary value: Sex ($3.873 in 2002) is an expensive word we read on the project webpage, much more so than ‘art’ (only $410 in 2002) but the real killer apparently is ‘free’, the most expensive word of all.

Both Adsense and Adwords are forms of ‘Googlization’. A term which, according to cultural historian and writer of the – soon to be published – book The Googlization of Everything, Siva Vaidhyanathan stands for Google’s strategy in choosing which information (of people) to render. These are usually types of information previously not seen as an economically viable raw material, so-called ‘commons’, which are effectively commercialised in the process. And although Google offers ‘opt out’ possibilities, according to Vaidhyanathan, those are in fact only usable for the ‘elite and proficient’. Ludovico illustrated the difficulty of really ‘opting out’ of Google as well when he showed the audience this satirical video by The Onion News Network:

Even the PHD researchers presenting their research into Google search strategies claimed that Google’s all seeing eye was troublesome for their work. Their (not quite) reverse engineering of Google’s Pagerank algorithm (their ultimate trade secret) took place in a grey area, being – logically – frowned upon by Google. Another similarity with the artists presented itself as well: as a research tool Martin Feuz’ site perspectoma.com is in fact a tool to see if, when and how Google Personal Search changes your search results, but because the ‘persons’ (or should I say simulacra?) the tool is set up with are philosophers Kant, Nietsche, Wiener, Foucault and Latour, it’s turned to be a cool and artsy gimmick as well.

Net.art has historically been bound to hactivism and the ideologically loaded beginnings of the net. In that sense it is not surprising that the gathered techno-geeks – whether scientist, artist or otherwise – at SotQ propose a rather activist approach when it comes to exploring the different boundaries of internet search. What is slightly disturbing is the real sense of ‘Big Brother watching you’ that crept through the ranks, which was less ephemeral as one would generally hope for. From a contemporary art point of view it is also disturbing to notice that even art that focuses on the aesthetic qualities of the internet (Google or otherwise) is seen as potentially (economically) harmful and will be censored without a second thought, pushing the boundaries of what should or should not be seen as (h)activism beyond the point of its intentions.

The conference felt a bit like a David and Go[og]liath story, be it one with an – at best – uncertain outcome. But the techno-elite wasn’t too worried apparently, because they happily multitasked through the afternoon listening and simultaneously collaborating on the cliff notes of the meeting using… wait for it… Google Wave. (Google’s latest service, currently available for beta testing by those who have managed to acquire invitations).

Luckily, not everyone let himself get drawn into Google-bashing. Pater familias Lev Manovich – instead of looking at the dangers of monopolizing information – looked at the potential of search engines as aggregates for bigger and less subjective forms of cultural research, citing (and showing) a short film on the cultural analysis of the entire oeuvre of Mark Rothko by UC San Diego in California. Which proves the point that it is not technology itself, which is bad or good, it is what we choose to do with it.

Saturday also boasted an evening on net.art, for more on that, visit de SotQ blog.