Afterlife

On 6 December 2012, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam hosted the symposium, Afterlives: Living the Past in the Present. The small event was organized in honor of Prof. Dr. Deborah Cherry, who will be leaving the position of Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at The University of Amsterdam by the end of this year.

Except for one discordant note on Cherry’s assumed problem with adjusting to Dutch culture, the atmosphere of this intimate symposium for colleagues and students who have worked closely with her over the past six years of her tenure was respectful and warm. Frank de Vree, Dean of the Faculty of the Humanities, opened with a word of thanks for Cherry’s overall academic achievements at the university, which was followed by praise for Cherry’s professional work and cordial character by colleagues from both the academic and the art world, and topped off at the end of the morning by convincing and heartfelt speeches of Cherry’s students, who paid tribute to her talents as a teacher and a mentor.

In response to Cherry’s request to focus the event on relevant issues relating to her current academic and professional work, the five presentations and subsequent round table discussion were organised around the idea of "afterlife." Rooted in Aby Warburg’s concept of Nachleben, which could be translated as both "afterlife" and "survival," the theme was inspired by Cherry’s ongoing research project on "Monuments and Memorials," as well as her forthcoming publication The Afterlives of Monuments, which on its turn was linked to a conference with that same name at St. Martin’s college of Art and Design in London (2010).

This international conference addressed the political, cultural, and religious meanings of the monument, which are never fixed but always in flux; that is, reinvented, re-used and transformed with ever-changing historical conditions and shifting political and cultural circumstances. Focusing on the monumental culture of South Asia, marked by its complex (post) colonial history, the aim of the conference was nothing less than to rethink the whole category of the monument beyond Western models.

The concept of "afterlife" was used in a much broader sense for the symposium at the Stedelijk, namely as a kind of time-based umbrella term to reflect upon "the complex relationships of past and present in contemporary art," and "discuss the ways in which the past disturbs, erupts, and intervenes in the present." This broad approach was probably chosen to connect the quite different, interdisciplinary contributions by speakers such as media theorist Sudeep Dasgupta, artist Wendelien van Oldenborgh, curators Galit Eilat and Natasha Ginwala, and art historian and conservation researcher Tatja Scholte.

The broadness of concept, however, was balanced by the way in which the presentations of the scholars and art professionals carefully intersected with Cherry’s varied work on visual culture, globalisation studies, feminism, museum studies and curating —materialized in the many books she (co-) edited, such as Art: History: Visual: Culture (2005), Local/ Global: Women Artists in the Nineteenth Century (2005), Spectacle and Display (2008), Location (2007), and About Mieke Bal (2008), as well as her research projects, such as Art and Cultural Politics in Post-9/11 Europe, New Strategies in the Conservation of Contemporary Art, and Cultural Translations in the Arts.

The expected consequence of this broad and interdisciplinary reading of Warburg’s concept of nachleben (afterlife) was vastly different presentations. Independent curator Natasha Ginwala, for instance, elaborated on the concept from the perspective of her curatorial practice. Ginwala mainly discussed the Museum of Rhythm, her curatorial contribution to the Taipei Biennale (2012). This anomalous museum consisted of a partially historical, partially fictional display of a wide variety of scientific objects and art projects relating to time, rhythm, measurement and regulation: from a space dedicated to the metronome, to the documentaton of an irregular swimming stroke developed by a Colombian artist, and an artistic project that translates a Google satellite photo of unknown white lines in the Gobi desert into a rhythmic pattern for textile design. Ginwala stated that she "brings together all kinds of things that have never been brought together."

In the process, she creates innovative exhibition models across cultures, space and time. From a quote of Henri Lefebvre, to which Ginwala refers herself, it is clear that the museum of rhythm touches upon the symposium’s concept of "afterlife:" "Are there not alternatives to memory and forgetting: periods where the past returns — and periods where the past effaces itself? Perhaps such an alternative would be the rhythm of history?”

Artist Wendelien van Oldenborgh gave a very different interpretation to the topic from the viewpoint of her cinematographic work relating to inter-cultural phenomena and their underlying global processes, which intersect with Cherry’s concerns about the culture and politics of globalisation. The artist showed excerpts of her latest film La Javanaise (2012), which is currently on view at the Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam. Van Oldenborgh’s work explores the ambiguous "afterlives" of the complex colonial and commercial relationships between the Netherlands and West Africa through the history, trade, and usage of one African fabric — known as ‘Hollandaise’ — produced by the Dutch company Vlisco since the 19th century after Javanese Batik techniques.

Van Oldenborgh’s multi-layered and densely scripted film — in which scenes performed by non-professional actors are alternated with a voice-over who reads excerpts of (historical) documents — stages a conversation between an African fashion model and a writer-artist about the cultural, political, and economic aspects of this hybrid cultural fabric, as well as the issues that it raises of colonial heritage, cultural identity and the global market system.

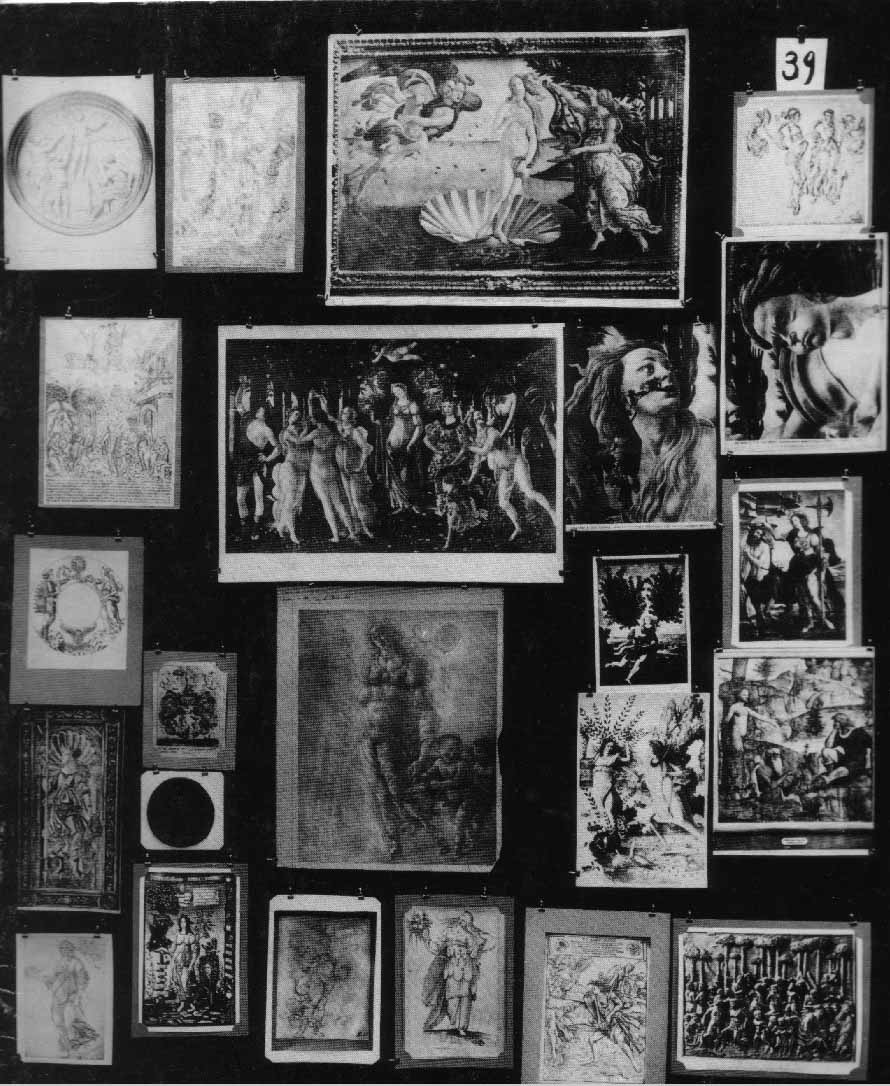

The other speakers came with yet different approaches to the concept of "afterlife" from a variety of disciplinary angles, such as art history and conservation practice. Of all presenters, Dasgupta gave the most art historical lecture. He engaged in a comparative analysis of the various paintings and photographs, and showed in historical and compositional detail how the process of visual translation — or "afterlife" in Warburg’s sense — works across media, especially in relation to questions of cultural identity and memory. Eilat drew somewhat disturbing parallels between surgeries of the human body and the restoration of artworks (fortunately accompanied by entertaining video clips), thereby raising pertinent questions of the whole culture of prolonging life and today’s obsession with material and physical perfection.

In the closing round table, Cherry eloquently took on the role of respondent and reacted to the different readings of "afterlife," thereby also taking the opportunity to clarify her postcolonial and Derridian position. Cherry’s interest in the concept came after a confrontation with the complex political, religious, and ethical history of (I believe) an Indian temple; any simple concept of the monument as symbolic representation is inadequate in the face of such sanctuaries in the living fabric of society. The message was clear: the concept of "afterlife" should not just be understood in a material, but also in a cultural, political, ethical, and even in a psychological sense. In Specters of Marx, Derrida explains that Marx’s legacy still haunts us. An "afterlife," Cherry concluded in a Derridian spirit, can be "a question of effect."

Front image: Wendelien van Oldenburgh, La Javanaise, 2012, currently on view at SMBA

Stedelijk | Symposium

Afterlives: Living with the Past in the Present

6 December 2012

Sjoukje van der Meulen

is kunsthistorica aan de Universiteit Utrecht en werkt momenteel aan een onderzoeksproject over hedendaagse kunst in de Europese Unie.