2017 Whitney Biennial

After seeing Jordan Wolfson’s virtual reality film Real Violence at the 78th edition of the Whitney Biennial, it has been haunting me for days. Even when I thought I finally got rid of it, it kept coming back when I closed my eyes.

The first shot shows a street with office blocks and high-end shops. The camera makes a sudden move just after you make a somersault in the air. You can hear the street noises, but now it is disrupted by Chanukah blessings. When you are back on your feet, still feeling a little dizzy, you come across a young man in a red sweatshirt, sitting in a cross-legged position on the pavement. He looks at you. He suddenly gets attacked from behind with a baseball bat. The other man (played by Wolfson himself) bites him until he drops, and continues to crush the head of the first with his foot. What happens after that, you can imagine. I could not watch the end, if there is any. This was already too much for me. Not without a reason, the adjacent room of the museum was filled with growing trees, an installation by Asad Raza. You can breathe again; it was just a movie.

Installation view of Jo Baer. Collection of the artist; courtesy Galerie Barbara Thumm, Berlin. Photograph by Matthew Carasella

Installation view of Jessi Reaves, Ottoman with Parked Chairs, 2017. Collection of the artist; courtesy Bridget Donahue, New York. Photograph by Matthew Carasella

The truth is that everyone can see Wolfson’s work at their own responsibility. You have to make an effort to watch it, wait in line, cross the sign ‘not for children under seventeen’, and put on the special 3D audio-visual equipment. The label placed on the wall reads: ‘we witness the artist himself engaged in an act of unexplained violence’. We seem to be accustomed to brutal images in everyday media, movies, or computer games. They are part of our daily life.

That evening, when I got home from the Whitney Museum, a video from another attempted terrorist attack at the Paris Orly Airport appeared in the news. The footage from CCTV showed the IS extremist grabbing a female soldier from behind. After three minutes, he was shot dead. The documentation was blurry and recorded from afar, while Wolfson’s V.R. film positions the viewer just in front of the victim, facing the crime scene. That is why Real Violence appears more ‘real’ than actual reality.

A few days later, another IS soldier caused deadly rampage in front of the British Parliament in London, when the New York art scene was busy with the controversy over Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket, about the 14-year old Emmet Till, brutally abducted and murdered, after being accused of whistling at a white woman, a cashier at a grocery store. Till’s homicide in 1955 galvanized the emerging Civil Rights Movement. Hannah Black, an artist and writer from the U.K., has launched a campaign calling the Biennial curators Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks for eradication of Open Casket, and even its destruction. ‘It is not acceptable for a white person to transmute black suffering into profit and fun’, she said.1

Even though there are more than sixty participating artists in the Whitney Biennial, Schutz’s paintings are mentioned in almost every review, and not only because of the debate around it. ‘Dana Schutz is a new master’, praised Peter Schjeldahl in The New Yorker.2 Roberta Smith, art critic of The New York Times, wrote that Shutz paints the pain of looking at the wounds.3 ‘If you think her work is not political enough, see her thick, sluicing Open Casket (…) and see if the idea of Black Lives Mattering does not crash in on you.’, adds Jerry Saltz, who called the 2017 Whitney Biennial ‘the most politically charged in decades’.4

Installation view of Henry Taylor, The 4th, 2012-2017 and THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH!, 2017. Collection of the artist; courtesy Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/Tokyo. Photograph by Matthew Carasella

The general premise of the longest-running survey of contemporary art in the United States, the Whitney Biennial, is to offer a ‘barometer of the times as experienced through art’.5 Trying to make an exhibition that is reflecting current socio-political feelings seems practically impossible. Especially in a pre- and post-election situation that the curators of 2017 Whitney Biennial had to face (starting in 2015 at the height of Obama government and concluding in Trump-era), it could be seen as tilting at windmills. ‘The result, which is earnestly attentive to political moods and themes, already feels nostalgic. Most of the works were chosen before last year’s Presidential election’, says Schjeldahl.6

But maybe the political preferences and social conscience do not change as fast as we perceive it. Racial tensions, economic inequities, and polarizing politics did not grow overnight, on November 8th 2016, with the election of Trump, who, after all, did not appear out of nowhere. As The New York Times pointed out, Trump appears in the exhibition only twice, but even when it is veiled, it still creates a strong statement. Like the graffiti on a brick-color wall ‘Fuck this racist asshole president’ photographed by An-My Lê (November 9, Graffiti, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2016).

Although the election may have had a huge impact on anxieties and fears harassing America, the show also reminds us that current problems have been around for much longer. Like the refugee crisis (brought up by Tuan Andrew Nguyen, who in his short video The Island tells the story of the largest and longest operating refugee camp after the Vietnam War set up on the coast of Malesia), the problem with the Mexican-American border (A Very Long Line, a video installation by artist collective Postcommodity), censorship (Frances Stark’s large-scale paintings of pages from Ian F. Svenonius’ book Censorship Now), or gun prevalence in the U.S. (remains parts of the guns destroyed on request of the artist known as Puppies Puppies for the series Triggers), to name a few.

Many works seem to ask what kind of country America is today, taking under a magnifying glass everyday humdrum. Jessie Reaves deformed hybrids of sculpture and furniture inhabit different locations of the museum, often replacing gallery benches. They look disturbing, as if they came from the house of an insane person, or as if they could engulf you the moment you sit on them. Deana Lawson’s intimate photographs made in people’s homes turn out to be carefully set up scenarios. Samara Golden’s eerie scale model of neither corporate office, nor beauty solon, that brings to mind hospital rooms or prison cells, comments on the disorientation and anxiety of our time.

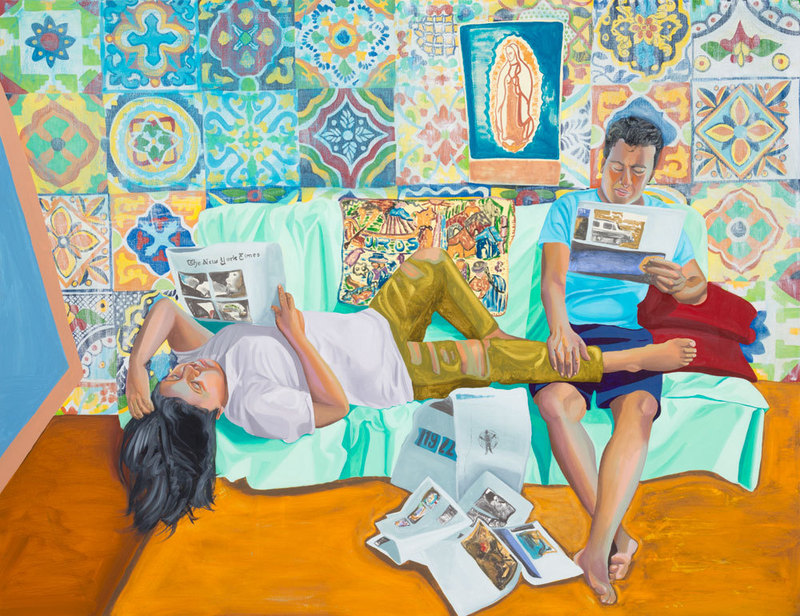

Aliza Nisenbaum, La Talaverita, Sunday Morning NY Times, 2016. Oil on linen, 68 x 88 in. (172.7 x 223.5 cm). Collection of the artist; courtesy T293 Gallery, Rome and Mary Mary, Glasgow

Installation view of Puppies Puppies, Liberty (Liberté), 2017. Photograph by Matthew Carasella

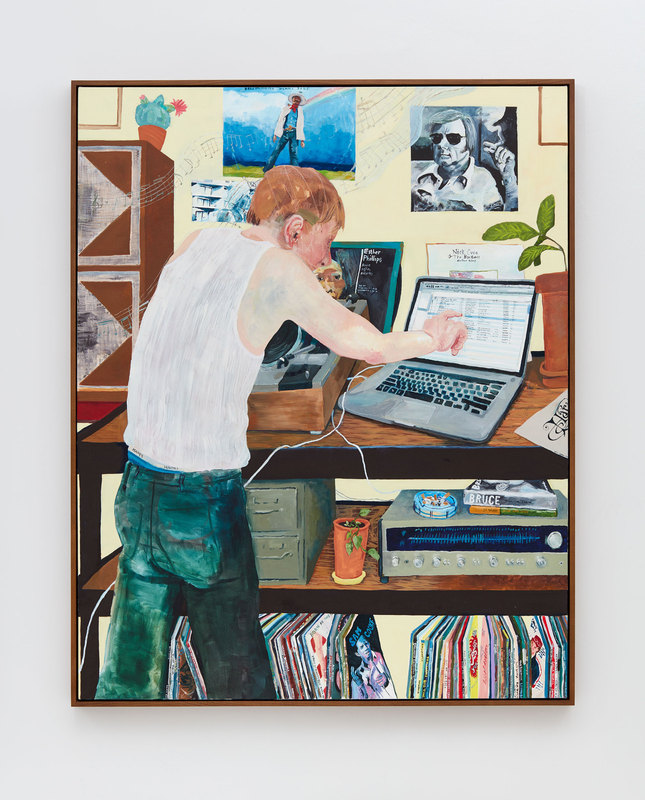

The quite impressive selection of paintings (a medium very often neglected) commenting American daily life deserves special attention. Apart from Dana Schutz, the work of Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Henry Taylor and Aliza Nisenbaum is worth mentioning; it documents the time in which we live. Whether depicting Donald Trump’s supporters, a succession of black men shot dead by the police, undocumented immigrants, people playing records at home, barbecuing, or reading The New York Times, the images resemble the deformed society of Harmony Korine’s movies.

Celeste Dupuy-Spencer, Fall with Me for a Million Days (My Sweet Waterfall), 2016. Oil on canvas, 60 x 48 in. (152.4 x 121.9 cm). Private collection; courtesy the artist and Mier Gallery, Los Angeles

The tension and polarity of American society before and after the 8th of November is made clear by a range of contrasts in the show. Traditional media (like painting or sculpture) are on a par with new technologies (virtual reality, games). Like in John Divola’s photo series Abandoned Paintings, where art students’ canvases are hanged in discarded buildings, the visually pleasing works in the exhibition are hanging next to more disturbing ones. Aside from the juxtaposition of Wolfson and Raza, the vibrant, colorful paintings by Carrie Moyer are shown next to Reaves’ unsettling furniture, the glittery, festive figures and stained-glass window by Raúl de Nieves (a big attraction for kids) are to be seen in the same room as Leigh Ledare’s 16mm film Vozkal shot in Moscow, portraying ‘society unconsciously shifting among various forms of dependency, pronounced individualism, and non-differentiation’.7

Surrounded by the white walls of the museum and the gallery guards in their dark uniforms equipped with buzzing walkie-talkies, I could not stop thinking about the assassination of the Russian ambassador at an art show in Ankara a few months ago, which made us realize that violence, politics and art are closer than we could have imagined. The photographs of this tragic event that quickly spread around the world were compared, again by Saltz, to the setting of The Oath of the Horatii, painted by Jacques-Louis David, or Falling Man, made by American artist Robert Longo.

What is the need and role of making shows using political and social unrest, distrust and anxieties? Do we need art to delve deeper into the horror that we are already aware of? Or do we need to stop being reminded? Does it serve something to show that in the age of political oppression we are not scared of it (or pretend no to be)? No matter what position the audience of the 2017 Whitney Biennial wants to take, or what questions beholders ask themselves, what matters is that it does not leave visitors indifferent.

Asad Raza Installation view Root sequence. Mother tongue, 2017. 26 Trees, UV lighting, Customized scents, carpet, cabinet with possessions of caretakers. Collection of the assembled Photograph Bill Orcutt

Installation view of Ajay Kurian, Childermass, 2017. Photograph by Matthew Carasella

Installation view of KAYA, SERENE, 2017. Photograph by Matthew Carasella

2017 Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, March 17-June 11, 2017

1 https://news.artnet.com/art-world/dana-schutz-painting-emmett-till-whitney-biennial-protest-897929

2 http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/03/27/the-whitney-biennials-political-mood

3 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/16/arts/design/why-the-whitneys-humanist-pro-diversity-biennial-is-a-revelation.html?_r=0

4 http://www.vulture.com/2017/03/the-new-whitney-biennial-is-the-most-political-in-decades.html

5 Biennial press release.

6 Biennial’s press release.

Weronika Trojanska

is kunstenaar en schrijft over kunst