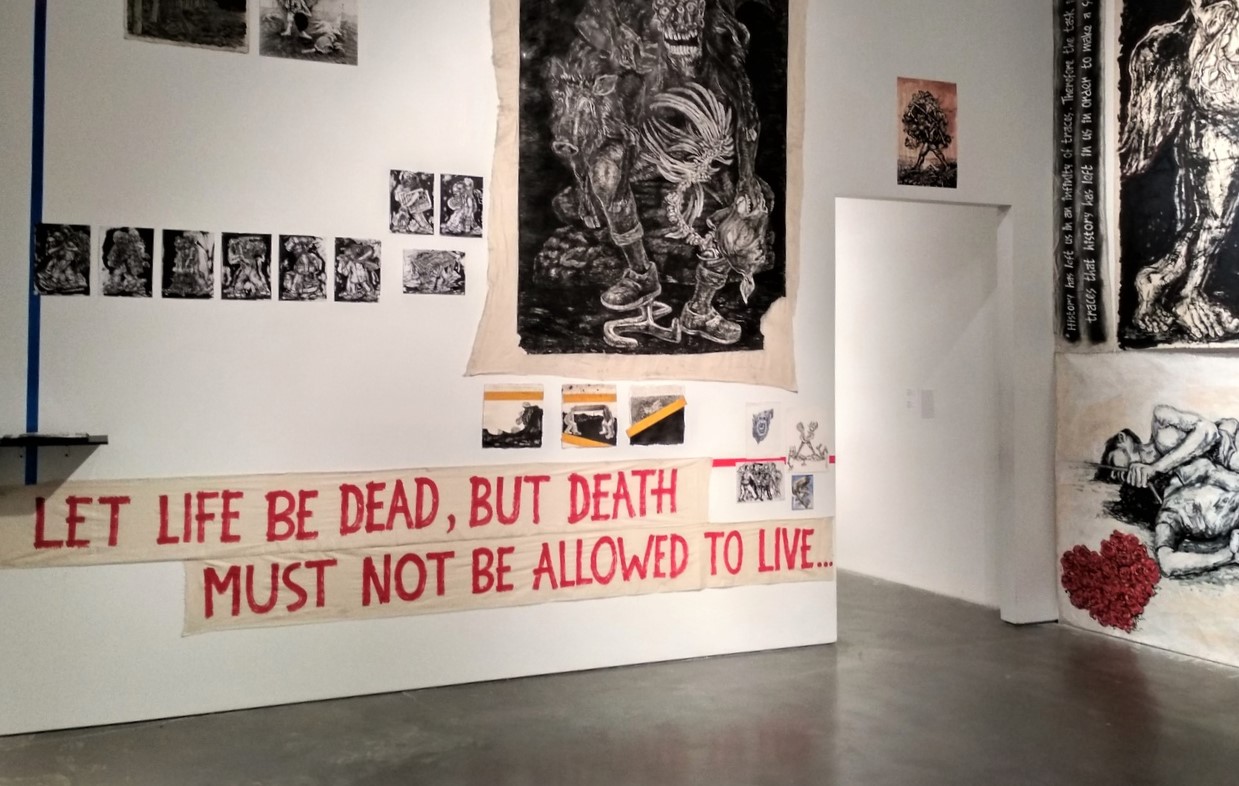

Anupam Roy, Surfaces of the Irreal, 2018, mixed mediums. Courtesy the artist, special thanks to Vadehra Art Gallery, Delhi

It’s political, it’s sensitive, it’s urgent – is it?

The New York Triennial claims to give voice to a generation of younger artists. And the young artist of today calls for action.

The first thing that comes to my mind when I hear the title of the fourth New Museum Triennial exhibition is Beastie Boys’ hit from the early nineties; “Sabotage”, and its vivid music video with scenes of high-speed car chases, where rappers take on the roles of police officers, modelled after opening credits of old action movies. “Cause what you see, you might not get, and we can bet, so don’t you get souped yet”, sings the band.

On the contrary, Songs for Sabotage – put together by the New Museum’s curator Gary Carrion-Murayari and Alex Gartenfeld, deputy director and chief curator of the Institute for Contemporary Art in Miami – appears calm, harmless, and even cautious. Works by almost thirty artists, collectives, and artists groups from nineteen countries from across the globe amount to “serve as calls to action against the systems of domination and exploitation characteristic of global capitalism today.” [1] Since over the past few years the sociopolitical turmoil is in the spotlight in practically every aspect of our life; from news in the global media to conversations at the local bar, it is no wonder that the show carries out issues such as common injustice, institutionalized racism, colonialism and post-colonialism, homophobia, migration and refugees crisis, to name just the most vibrant of current affairs. But the thing with long time-spanning exhibitions is that usually the arrangements for the next show start some years prior to its opening (three in terms of a triennial, to be precise), and thus the issues it touches upon are more universal ones whose urgency won’t expire before it opens to the public.

2018 Triennial: Songs for Sabotage. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

“I can’t stand it, I know you planned it, I’m-a set it straight this Watergate”, begins “Sabotage”. At the first sight, the video by Greek artist Manolis D. Lemos slightly reminds me of Beastie Boys tune. In this three minutes-clip the camera follows a large group of hooded figures in spray-painted raincoats running in various constellations through the empty streets of Athens, accompanied by a leftist pro-democracy song in the background. But quickly it turns out that this slightly ironic image of tourism and the capital of Greece as a riot town is more like a street ballet than a rebellious act. Even the title of the work – dusk and dawn look just the same (riot tourism) – sounds more like a line from lyrics of a romantic ballad than of a protest song.

2018 Triennial: Songs for Sabotage. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

Manolis D. Lemos, dusk and dawn look just the same (riot tourism), 2017, single channel video, color, sound. Courtesy the artist and CAN Christina Androulidaki gallery, Athens

In the same room as the video, the central position is taken by a life-sized ascetic metal swing set, like the ones at children playgrounds; E.I.G by Brooklyn-based artist Diamond Stingly, with a ladder leaning on its side and a brick placed on the metal bar above the seat. It doesn’t encourage one to swing and the rungs seem to lead nowhere. However, while I was looking at it someone found it inviting enough and tried to sway, which resulted in the immediate arrival of a group of security guards (even together with the New Museum’s artistic director Massimiliano Gioni) asking the delinquent to move away immediately. “These structures suggest interaction accessible only through associations; they reverberate with a foreboding absence, the bodies once activating these spaces now only existing in memory”, resounds nostalgically the E.I.G description in the triennial’s catalog.

Interactive installation and new media art form the minority of the Songs for Sabotage exposition. It seems to be particularly interesting, especially for young emerging artists (between the age of 28 and 35), that the show appears rather “analog” than “digital”. Among the works traditional media such as painting, sculpture, ceramics and tapestry predominate. It might both represent the overall exhaustion of “post-internet” art and its derivatives or deliberate curatorial choices: worth mentioning here is the fact that the New Museum Triennial team made several trips across the world to artists communities that were digitally not accessible. “All these artists using a variety of tools trying to build community and dialog around. There is both an urgency in their work but also kind of lyricism and seduction that is important in getting their voices and messages across”, said Gary Carrion-Murayari.

If one compares this exhibition to a music composition, everything seems to be sung on the same octave, missing the focal point, as a so-called crescendo

2018 Triennial: Songs for Sabotage. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

The exhibited works create the impression of being in constant dialogues with each other but they rather speak than scream. Even if some of them appear to be more compelling than others, it’s been difficult for me to even highlight some specific examples here, they blend together with other pieces. If one compares this exhibition to a music composition, everything seems to be sung on the same octave, missing the focal point, as a so-called crescendo. This could be actually seen as an asset – the exhibition represents the voice of a generation rather than favoring individual artists. But I am also wondering whether the communication happens more on the aesthetic level than on a semantic one. The whole exhibition, which occupies almost the entire building of the New Museum has a clear and cogent composition of display, of which deliberate curatorial decisions turned out to be decidedly visually pleasing. Works placed next to each other coexist in peculiar ocular riddles. Particularly appealing, to me, is the harmonious juxtaposition of Danila Ortiz’s colorful and intimate ceramics, which in fact are a proposal for a monument to indigenous leaders and criticism of the slavery, both during the colonial period as well as today, with the graceful forms and tones of paintings depicting various rituals, somewhere between violence and healing, by the Brazilian artist Dalton Paula, and the abstract pastel constellations on Tomm El-Saieh’s canvases in his series “Walking Razor”, which is inspired by the song of the same name by reggae musician Peter Tosh. Something similar happens in the case of the display of Janiva Ellis’ and Manuel Solano’s figurative paintings and Matthew Angelo Harrison’s encased second hand West-African totemic sculptures.

“New Museum Triennial looks great but plays it safe”[2], states the title of the New York Times review, with which I personally do agree. Indeed, Songs of Sabotage seems to remain a bit withdrawn from the current issues, like it wants to address them but without taking a stand or making strong commentary statements. Maybe this is a safe position because we live in a time of socio-political changes that we don’t yet quite know how to address? The artists in Songs for Sabotage are “beset by economic and social insecurity regardless of the overall wealth of their respective nations.”[3] They “offer models for dismantling and replacing the political and economic networks that envelop today’s global youth.”, claims the curatorial statement. But what’s political in the exhibition doesn’t really happen on the legislative level. The political happens on a position of the local art community that doesn’t support young artists in a way like many institutions in New York City do, where often they have to fight not only for their work to be disseminated into the public realm but also for the freedom of expression. Many of the presented works could be prohibited in their homelands, like Cannon Fodder / Cheering Crowds by the Amsterdam-based Peruvian artist Claudia Martinez Garay, which is another take on the problem of propaganda and abstraction. “If I present this work in Peru I could maybe be banned for example but here I can present it”, said the artist.

Just like the Beastie Boys’ music video is a pastiche on action movies from the seventies, Songs for Sabotage is “looking back to the 80’s when junk art became fashionable and became contemporary visual and marketable disease”[4], as someone commented anonymously on the triennial review at the NY Times. “The thing with so much ‘art’ nowadays is that it is unpleasant. It’s garish, careless, trite, lacking fundamental insight. Why is that?”, added someone else. “What could it be – it’s a mirage. You’re scheming on a thing, that’s sabotage”.[5]

Songs for Sabotage, 2018 Triennial, New Museum, New York, t/m 27.05.2018

* ”Sabotage” by Beastie Boys

[1] Catalog “Songs for Sabotage”, ed. by G. Carrion-Muryari, Alex Gartenfeld; New Museum and Phaidon, 2018, p.20

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/22/arts/design/new-museum-triennial-political-art.html

[3] Catalog “Songs for Sabotage”, ed. by G. Carrion-Muryari, Alex Gartenfeld; New Museum and Phaidon, 2018, p.20

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/22/arts/design/new-museum-triennial-political-art.html

[5] ”Sabotage” by Beastie Boys

Weronika Trojanska

is kunstenaar en schrijft over kunst