Dissident Gardens. Gardening Mars.

The Human Insect

What do insects, architecture and the radio have to do with one-another? The Human Insect: Antenna Architecture 1887- 2017, one of five exhibitions put together under the title Dissident Gardens at Het Nieuwe Instituut, explores potentials for an insect-like architecture.

Five exhibitions at Het Nieuwe Instituut, united under the overarching thesis Dissident Gardens, focus in varied ways on expressions of the classic struggle between nature and culture. In the display of works by artists, designers and architects spread out over the ground and first-floor gallery spaces, viewers are invited to engage with current developments in man’s relationship to the natural world through Biotopia, Smart Farming, Gardening Mars and Pleasure Parks. The entire upper floor, dedicated to the exhibition The Human Insect: Antenna Architecture 1887- 2017, is the focus of this review. The exhibition is curated by former dean of Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP), Mark Wrigley, a curator, academic and architect who is renowned for his extensive writings on the theory and practice of architecture. Wrigley is also one of the co-founders of Volume Magazine together with Rem Koolhaas and Ole Bouman.

The ground-floor gallery, an exhibition layout by artist Frank Bruggeman, is shaped around a giant red hill representing the landscape of Mars. Above and protruding from this hill, in scientific-like displays, vitrines and even a container, are explorations into human interventions on the natural landscape, organised in a circular-walkthrough of each section. Entering into the space anti-clockwise, the first section one encounters is Biotopia; a lab-like (everything feels like this) presentation of fungi and bacteria dyeing textiles which demonstrates how designers are moving more in the direction of researchers and are thus seeking new ways of applying natural processes in the design process. Smart Farming, as its name implies, discusses The Netherlands as a worldwide leader in agrarian innovation, whilst Gardening Mars takes the red planet as an untouched landscape of future opportunities. Finally, in Pleasure Parks, holiday parks are a manifestation of the relationship between the city and countryside and offer an escape from urban life.

[blockquote]What happens not if, but when, systems we continue to applaud do not function? What tools do we need at present to counteract glitches to the current system?

Dissident Gardens. Gardening Mars.

Dissident Gardens. Pleasure Parks.

For an exhibition centred on the tensions existing between man, the ‘manmade’ and nature, the display is, overall, quite formal and could have benefited from an alternative to man’s ‘seeming’ conquest over the natural world, with interventions where this is not the case. There is no engagement with possible disastrous consequences which Smart Farming suggests in showing how ‘food production now leaves no place for humankind’ as we become replaced by drones, robots and laptops. In other words; whilst celebrating the achievements of efficient agricultural systems of which The Netherlands is an apt example, there was no mention of climate change, its effects and the dark side of techno-influenced modes of production. Putting it simply, which alternative models might be offered to what has been achieved so far? What happens not if, but when, systems we continue to applaud do not function? What tools do we need at present to counteract glitches to the current system.

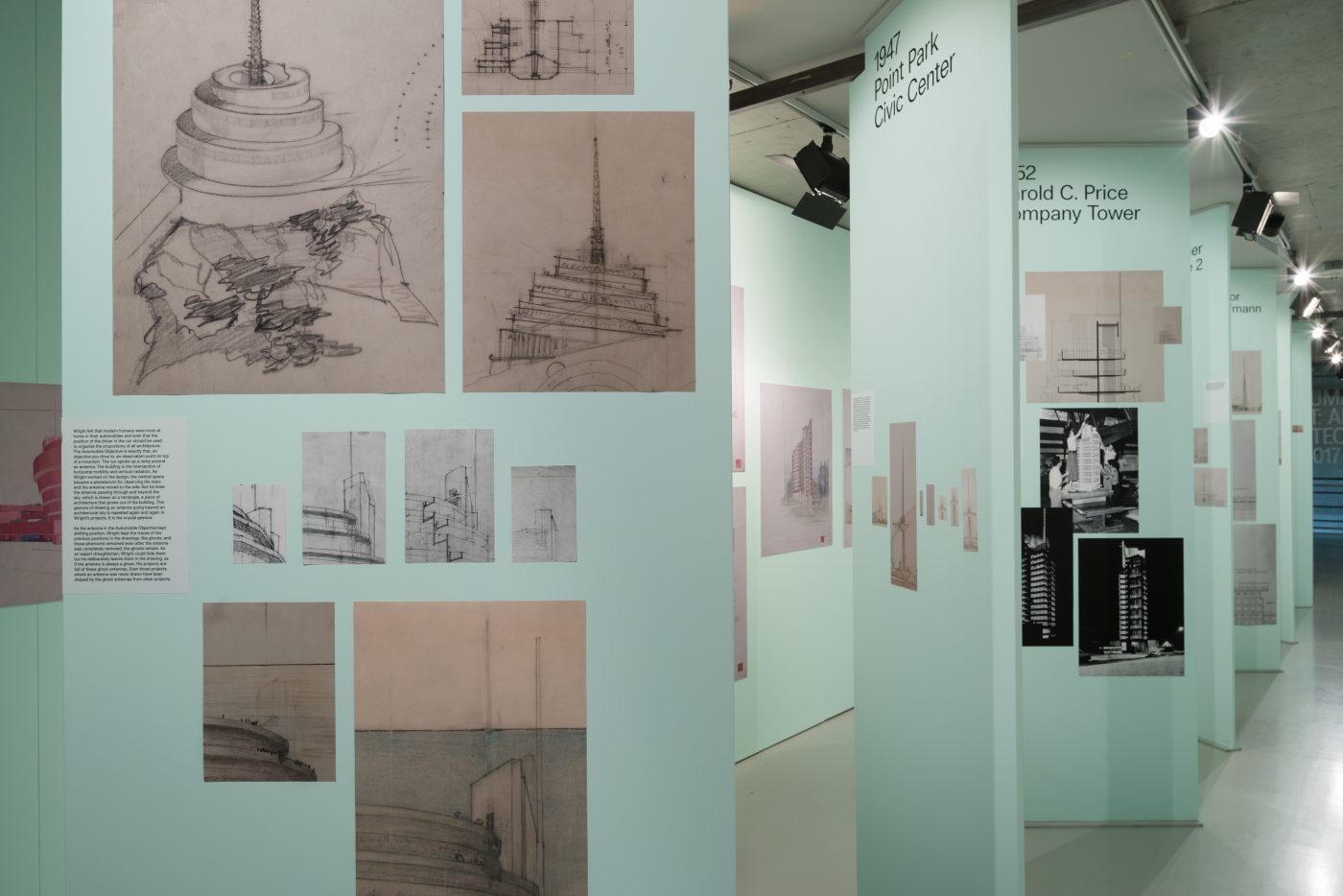

The Human Insect: Antenna Architectures 1887-2017. Foto Johannes Schwartz.

Wrigley’s Human Insect answers some of these critical questions by offering an alternative in a call for rethinking the relationship between humans and architecture, through a critical analysis of how the built environment deals with the invisible, in this case, electromagnetic waves via the antennas which facilitate our current society’s functioning. Likening this form of engagement between people, buildings and technology to the way ‘the insect’ exists in the world through antenna navigation, his central argument is that both human and insect species use ‘antennae to mediate the world and each other, and in turn, this allows us, humans, to organize ourselves across the world.’ Insects have existed for 400 million years, and these invaders enter every crevice, crack, gap and opening of buildings without invitation. Insects, with the use of the antennae, negotiate the world around them and each other, and in a similar way with the invention of the radio antenna, humans become insect-like as well. Wrigley discusses the architecture of information flows that traverse our living environment, as well as the effect they have on the design of that environment. He addresses what this means for the way our environments are shaped, their interiors, buildings and landscapes through examples from the late 20th century to the present, looking at how architects considered, experimented and ultimately forgot about the influence of radio on architecture.

As opposed to architecture taming technology, as has become normalised in how it usually hides parts of buildings that should not be seen – wires, pipes, and ultimately, flows of information, it is the architecture, he notes, that sits within a complex entanglement of radio waves. This observation begins with the prominence of grand antennas on top buildings during early transatlantic transmissions, to the present where numerous radio transmitters are hidden away in technologies such as the mobile phone some of which make us locatable at any given time. Architecture is filled with wires connecting us all, but the buildings themselves exist on a much smaller and less significant scale in comparison to the complex wired web within which the built environment is situated. Ultimately by looking back on the history of the antenna, Wrigley wants us to consider how technology has and continues to change us, in a way that we are never able to see in its present form, only via what has come before.

Insects, with the use of antennae, negotiate the world around them, and in a similar way with the invention of the radio, humans have become insect-like too.

The Human Insect: Antenna Architectures 1887-2017.

The Human Insect: Antenna Architectures 1887-2017.

The exhibition, designed by architect Andrés Jaque, founder of the Office for Political Innovation, begins with reproduced historical drawings from cities like Baghdad and New York of prominent antennas atop buildings which would bring populations across the planet together. Diverse examples show the scale of this antenna age in various building typologies (universities, museums, civic buildings, towers and even on ships) with American architect, Frank Lloyd Wright dreaming of transmitters atop a building called the Illinois that claimed to reach every television set in the nation. It began with inventions from the days of Marconi to monumental masts, and, now, in the present they completely disappear and become a sort of prosthetic extension of daily life. A vivid blue timeline, one of the largest parts of the show, begins in the year 1901 when the first antennae were used to radio broadcast across the Atlantic and ends with the future, through contributions of visitors of the exhibition. The space is filled with drawings, sketches, photographs and a maquette, all of which show the transgressions of antenna technology. The blue timeline, turning into another corridor, becomes a red and interactive one which looks at Russian contributions to antenna technology after the Bolshevik revolution, including Shukhov’s radio tower built in 1919, and Monument to the Third International (1919–20), a vision for a 400m iron, glass and steel constructivist tower by artist and architect Vladimir Tatlin planned for St. Petersburg but never realised.

The Human Insect: Antenna Architectures 1887-2017.

Walking through these displays presenting a forgotten history of the revealing and concealing relationship humans have to radio and architecture, showed me an untapped potential of an exchange that connects buildings and in turn humans to the invisible world of signals. This exhibition goes beyond ‘architectural thinking’ as we know it today and asks to embrace the unwritten history of the antenna to allow a framework for open thinking that posits new much-needed models to help move beyond current technophobia and think how we might implement creative, efficient, and sustainable solutions. Some of these models are left unexplored in Dissident Gardens overall, but with The Human Insect, in my view, a call to look beyond architecture as we know it seems the right direction to begin tackling issues that arise from global warming, climate change, dwindling natural resources and so on.

All photos by Johannes Schwarz

Dissident Gardens, until 23.09.2018, Het Nieuwe Instituut.

Jareh Das

is een schrijver en curator, momenteel verblijvend in Rotterdam, die schrijft over kunst, mode, muziek en cultuur