Saddie Choua,‘Lamb Chops Should Not Be Overcooked’

Undoing the biennale in three acts – the final phase of Coltan as Cotton, Contour Biennale 9

This year’s Contour Biennale stretched over a year with public manifestations in three weekends, recalibrating the conventional biennale format. Throughout the yearly moon cycle of the experiment that was Coltan as Cotton, one couldn’t tell if things had come to an end. Does it matter that there was no conclusion or finalised outcome?

This concluding phase of Contour Biennale 9 Coltan as Cotton in Mechelen was, just like the two previous public moments, synced to the moon cycle. This time, it was the turn of the waning crescent moon. A phase that may not be as evocative and mystical as a full or a new moon, but one that does point to an ending and hence to a new beginning, opening up the perspective of the future. Throughout the three days, again, conversations and performances reigned, focused on a future political climate that is only getting dimmer, as the curator’s 9th edition Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez signalled on different occasions.

If the first two public manifestations tapped into the discursive and participatory realms, this one pushed this strategy even further. In the main exhibition space, different artworks lay still, as if expecting to be stirred up by a new piece of information: a film, a performance, or even a series of walks in Fukushima. The collective Call it Anything, composed of academics and artists, organises tours in North-Eastern Japan, not that far away from where the disaster occurred on March 11 in 2015. Their goal is to induce a different gaze on what happened, one that moves away from the predictable spectacular imagery of the catastrophe. In the space, their contribution showed a text, layered over photographs taken during their Japanese drifts. If Call it Anything opted for a more conventional cinematic configuration, the Japanese artist Hikaru Fujii took the path of a lecture-performance. Les nucléaires et les choses bears on the fate of a displaced museum collection in the immediate proximity of the Fukushima power plant. While his project will eventually take the form of a film, his contribution to the biennale was to share some preparatory stages of the undertaking. The same goes for Raphaël Grisey’s and Bouba Touré’s long-term research collaboration on an agricultural cooperative in Mali. Their film Crossing Voices-Xaraasi Xanne (a title followed by the telling addendum work-in-progress) is in fact a rough cut. The screening was followed by a stimulating discussion on the broader geopolitical potential of the cooperative, especially for the historical context of postcolonial nation-building. The unfinishedness of such projects (and topics) is a provocation to wonder if the white cube, in its inertia, is still an apt environment for such works.

Hikaru Fujii, 'Les nucléaires et les choses’

Call it Anything, 'Along the Coast’

Even though the discursive tendency of the biennale, as well as its expansion beyond the institution (both in time and space), is nothing new, this final weekend of the Contour Biennale 9 highlighted this configuration in a unique way. In practice, what does it mean to condense all your efforts into exhibiting a process? What kind of curatorial challenges emerge? And to what end is the perennial exhibition model revisited? The projects mentioned so far testify to a certain “ongoingness”. Either unfinished or fragmentary, they unmask stages of the creative process we don’t usually get to see. They reflect on the process of production and development and unveil it. This change in labour conditions and exhibition visibility for the artists can, nonetheless, upset those who bank on the maximum exposure a 3 month exhibition allows for. However, it can also give rise to more freedoms, such as the possibility of in-depth engagement with a group. This was the case for Robin Vanbesien’s The Wasp and the Weather. His work is immersed in the history of the Mechelen youth center Rzoezie. Different members of that community wrote poetry in the eighties and nineties relating to the experiences of racism and loneliness that an immigrant might go through. After interviews, archival research and a re-enactment of the poems in public space during the second weekend, Vanbesien created a film. Poetry’s filmic resonance made the bottled feelings of estrangement surface in a new mode of awareness. Such projects echoed previous iterations of the same works, as seen in the first two weekends, allowing the visitor to witness a continuity and maturity in the artist’s thinking.

Bie Michiels, 'The Copy'

Raphaël Grisey en Bouba Touré, 'Sowing Somankidi Coura, a Generative Archive’

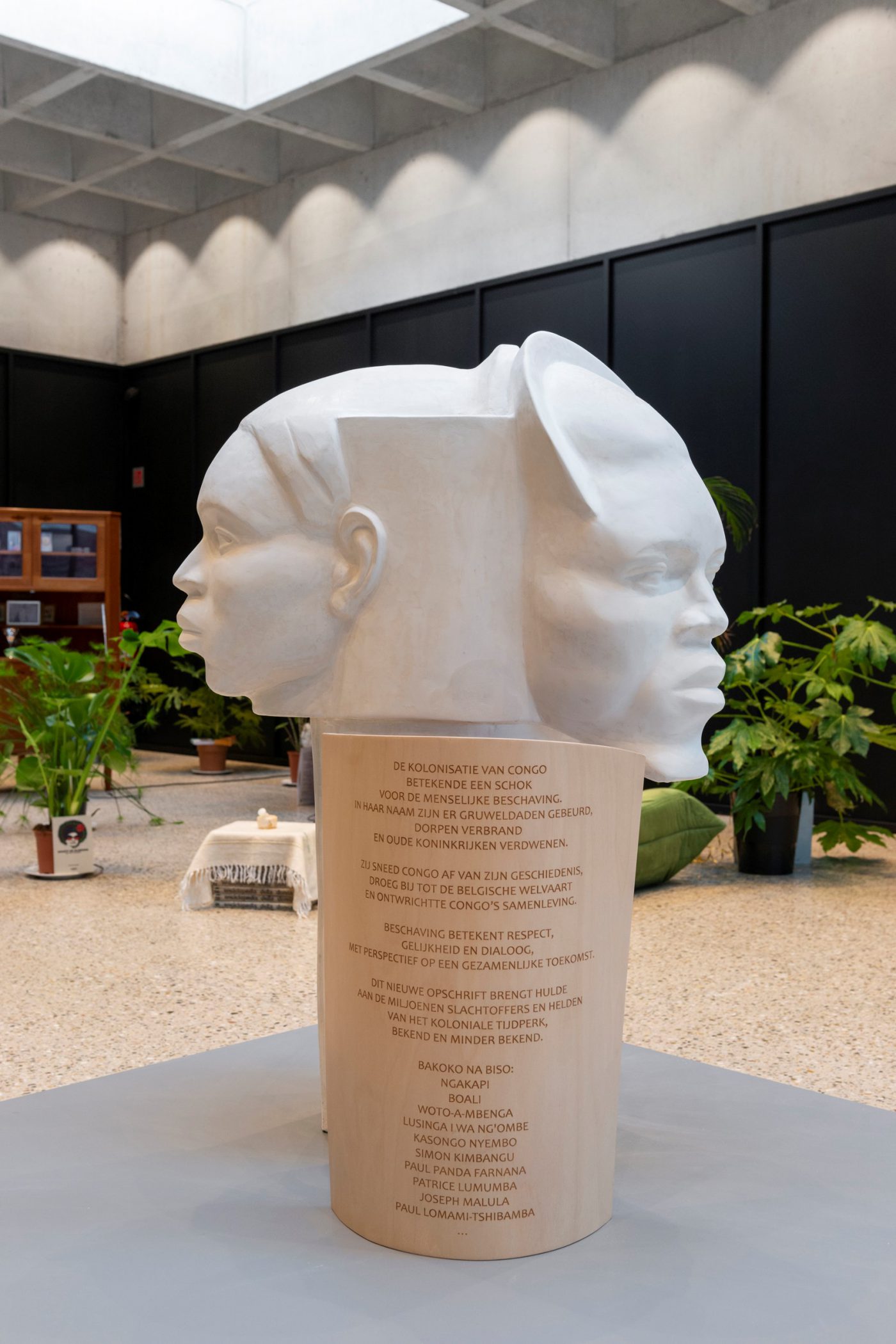

The same goes for Saddie Choua’s installation Lamb Chops Should Not be Overcooked, which extends the artist’s previous intersectional explorations. Choua’s installation welcomed women who had gone through the experience of racism to sit down and look through the pages of writers and activists such as Maya Angelou or Audre Lorde. A moving contribution that in some alternative universe might come close to what a safe space should feel like. Even though Choua’s contribution wasn’t as firmly rooted in the locality of Mechelen as her previous participation was, the problematics of locality did play out for Coltan as Cotton. The mayor of Mechelen, a persona already referred to in quite a few projects throughout the 9th edition thanks to his winning the World Mayor Prize in 2016, was convoluted in Bie Michels’ (Pas) Mon Pays, Part I and II. The film recounts an attempt to rewrite the inscription of a colonial statue in Mechelen and questions why a fully white team was commissioned by the municipality for the purpose. While global in scope, similar site-specific commissions achieved a locally embedded endeavour.

Contour Biennale 9 raised probing questions around what the role and form of a biennale should be. For the cynical gaze, a biennale is just another Western typology of exhibition making, a symptom of our drift towards spectacle. For the optimist, it is a site of experimentation, full of potentialities. Contour Biennale 9 fulfilled that promise. Throughout the yearly moon cycle of the experiment that was Coltan as Cotton, one couldn’t tell if things had come to an end. But it didn’t matter, or so I told myself, that there was no conclusion or finalised outcome. Should an artist begrudge corrections, deletions and more generally all these in-between stages? A well-made artwork feels just right, as if concluded at the most accurate moment of the creative process. Coltan as Cotton both defied and complicated that truism. It brought these states of incompleteness to bear on the biennale format: a risky endeavour, for sure, and one that left many questions unanswered. But also one full of the potential to generate unexpected situations, both for visitors and artists (who for the most part were present throughout the weekends). All the better, since the topics addressed, from radioactivity and extractive colonialism to intersectional resistance are issues we will need to face for some time yet.

Read reviews of the first two public moments of Contour Biennale 9 HERE and HERE

All images courtesy Contour, Photographs by Lavinia Wouters

Waning Crescent Moon Phase, the third weekend of Contour Biennale 9: Coltan as Cotton took place from 18.10 until 20.10.2019 in Mechelen

Kyveli Mavrokordopoulou

is doing a PhD at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris, on expanded notions of time in environmental art