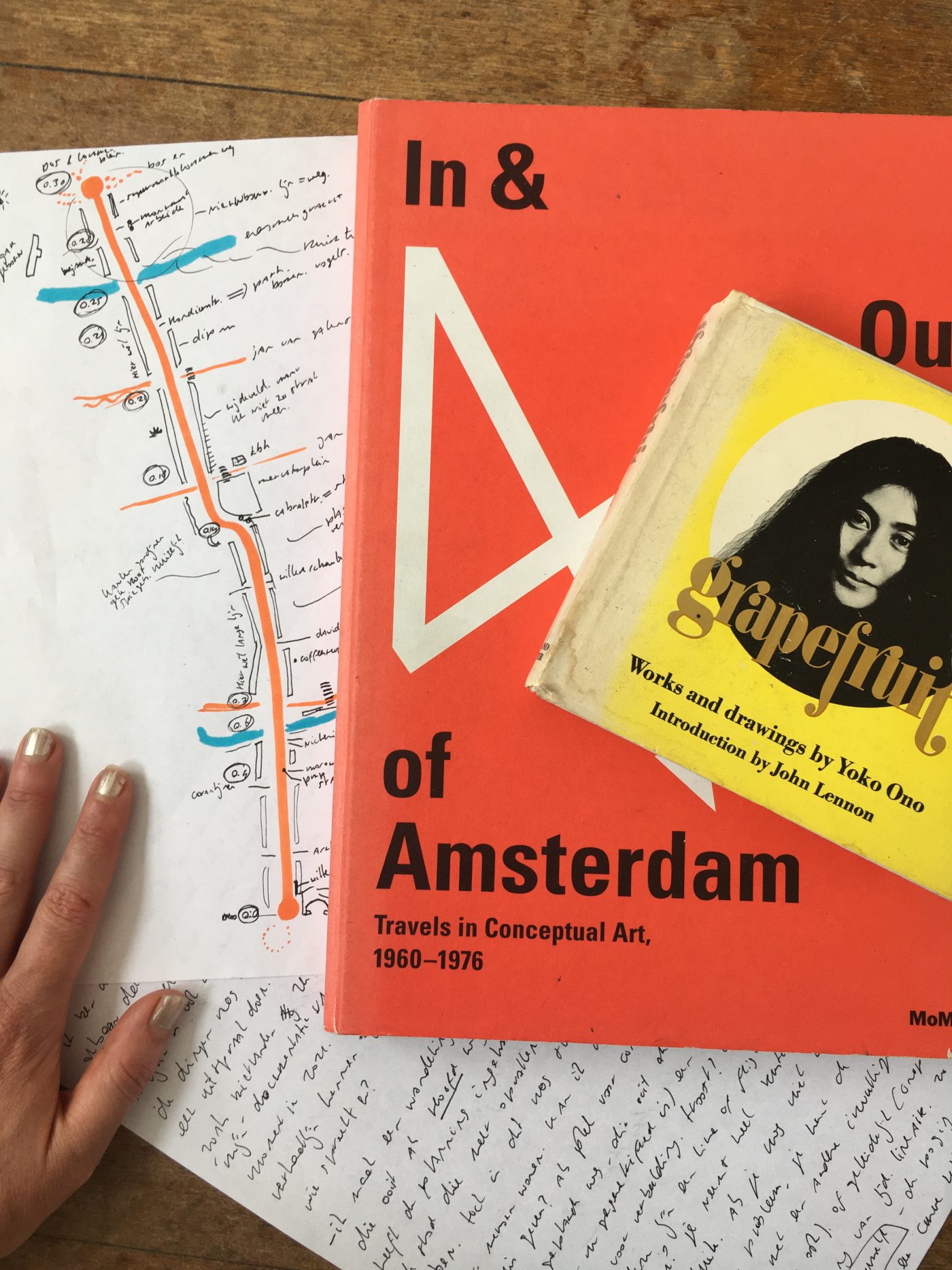

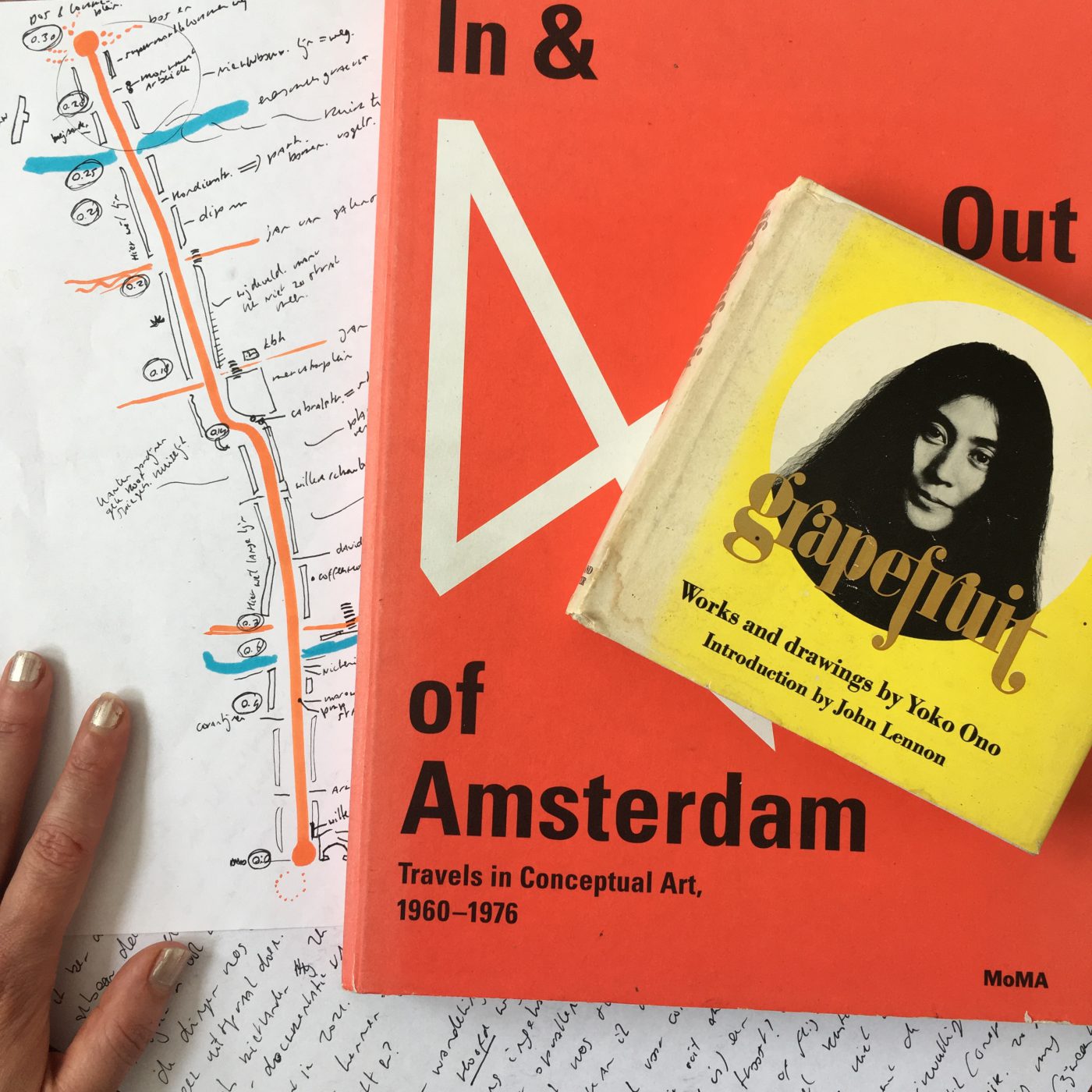

Hoofdweg (a possible line) work in progress, featuring notes, a script and the publications In & Out of Amsterdam / Travels in Conceptual Art (MoMA, 2009) and Grapefruit (Yoko Ono, 1970 edition), image by Radna Rumping

Tracing Lines: Radna Rumping’s Hoofdweg (a possible line)

Radna Rumping’s audio essay Hoofdweg (a possible line) leads through the longest street of Plan West in Amsterdam, the Hoofdweg. Manuela Zammit donned her headphones and started walking, before sitting down with Rumping to discuss the phenomenon of the artist walk, conceptual art, and the context of Amsterdam.

Rumping’s audio walk starts at Surinameplein, under the gate at nr. 2, and ends at nr. 718 near Bos en Lommerplein, with various opportunities for a break along the way. Through my headphones, Rumping’s commentary undulates between expressing her internal state of mind and making observations or telling stories about her urban surroundings. Rumping traces several possible lines: the one she and her listener traverse physically, the connection between the individual’s psyche and the city, and between the past, present and future of Amsterdam. In passing she also draws various lines of inquiry, questioning, for instance, the underrepresentation of female artists. The work is part of the project Welcome Stranger, for which several artists were invited to create works around the facades of their own houses in Amsterdam.

Photograph made during a walk along the Hoofdweg. Photo by Radna Rumping.

Photograph made during a walk along the Hoofdweg. Photo by Radna Rumping.

Rumping’s work descends from a long history of artistic practices that attempt to blur the boundaries between art and everyday life by walking in the city. It also forms part of a series of artworks initiated by Welcome Stranger, focused on showing art from artists’ private homes and in unusual places. After setting out to retrace the artist’s footsteps along the Hoofdweg, I sat down with Radna for a conversation about the affordances of listening and walking, architects with big plans, and how it’s never too late to become an artist.

What are your thoughts about the possibilities and potentials of the audio walk as artistic medium?

Although I have often worked with audio before, and walking or other forms of bodily movement/awareness have played a role in previous texts, this is the first time I made an audio essay with an actual walk in mind, as a work in the public space. It’s something I’d definitely like to explore more. With a work that asks to be listened to, I think it helps to involve other senses without letting them overrule the listening experience, but rather to enhance it.

With walking, different possibilities come into play. After a while, our bodies relax while finding a pace. An important part of Hoofdweg (a possible line) is that it is not a tour: one does not need to find the way, because the road is already there. One can simply press play and walk in a continuous straight line, following an existing road. This gives space to focus on listening to the text, combined with personal observations of the environment which will be different for every participant. Each walk is different, there is an element of chance far beyond my control, depending on other sounds in the environment, behaviour of passers-by, the time of the day, the weather, the mood of the listener…

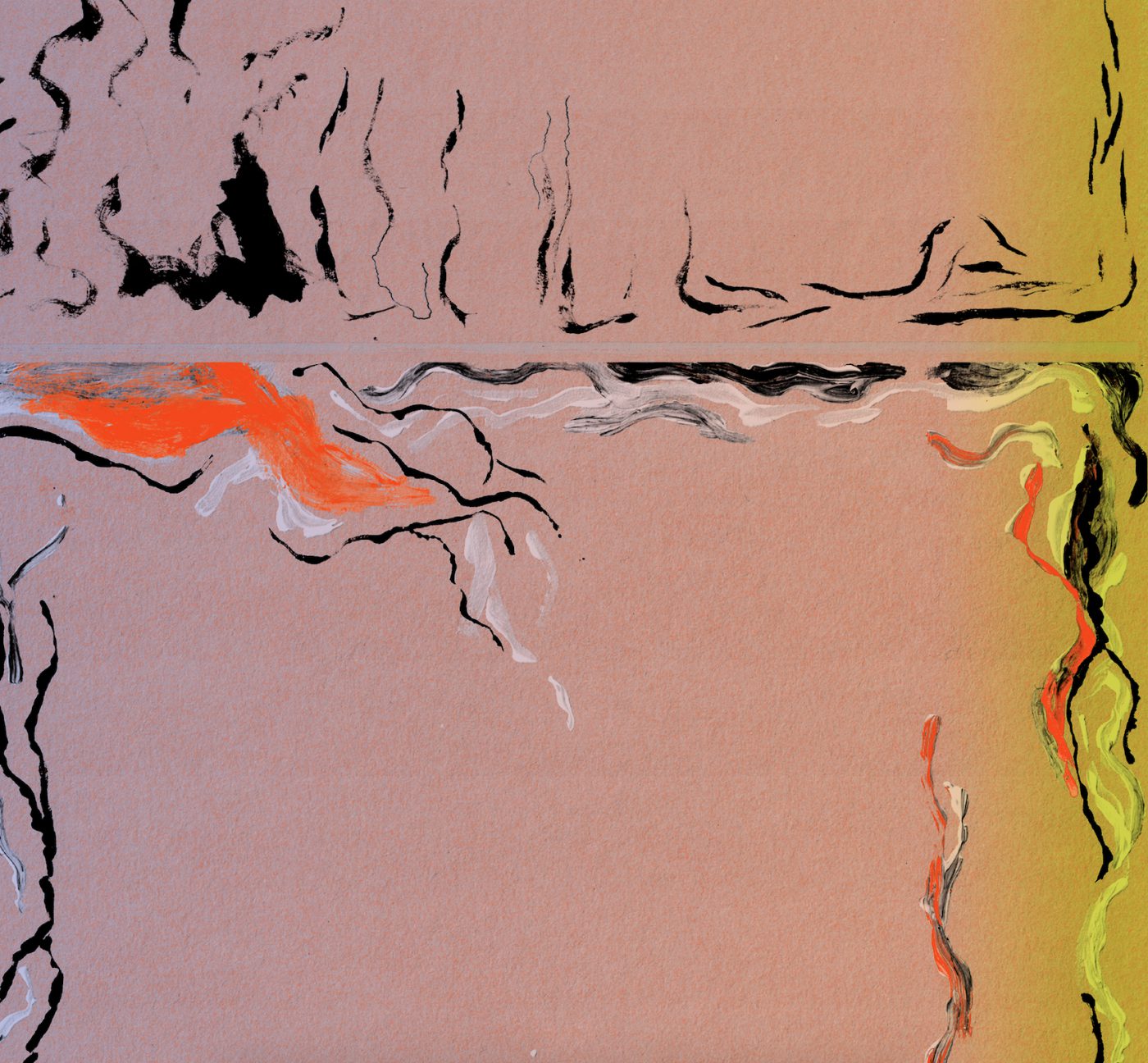

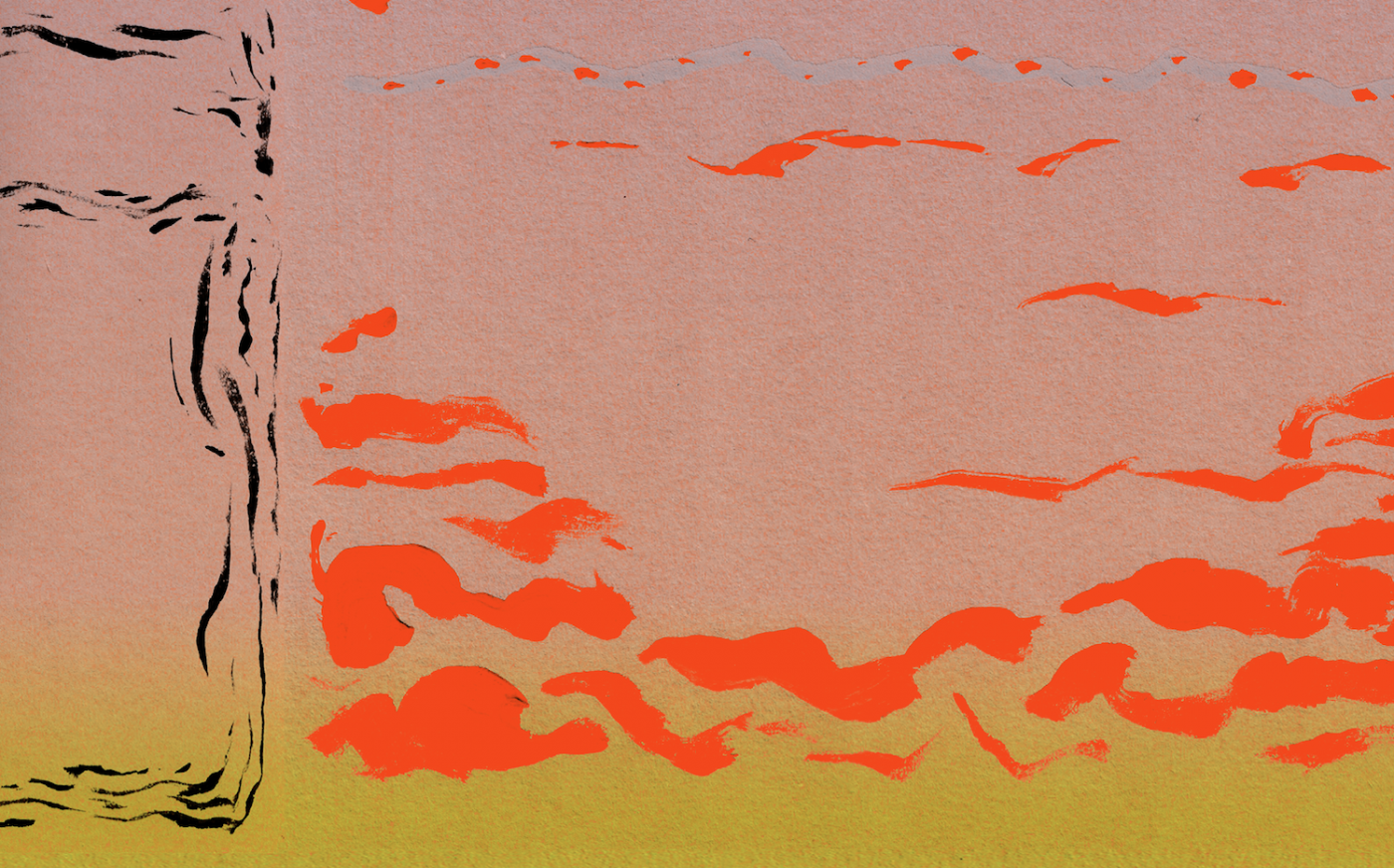

Detail of print for Hoofdweg (a possible line) designed by Rietlanden Women’s Office (2020)

Detail of print for Hoofdweg (a possible line) designed by Rietlanden Women’s Office (2020)

Another aspect of the project involved delivering a print designed by Rietlanden Women’s Office (RWO) containing a fragment from the sound piece to all the residents of the Hoofdweg. What was the idea behind this gesture?

Welcome Stranger invited me to make a work using the façade of my house as a starting point. While other participating artists have made works that are visible directly at the façade (in various ways), my work is not directly visible. It’s also not possible to take the work in at a glance; an audio essay asks for quite a lot of engagement from the listener. Still, I wanted all residents of the Hoofdweg to have a chance to get to know about the work, and also to receive a part of it.

The print designed by RWO is a small and delicate art piece by itself; it’s partly an abstract illustration and partly an invitation to listen to the audio piece and do the walk. They were hand-delivered door to door (to all 2005 addresses on the Hoofdweg) by myself with help from Alina Lupu and the team at Welcome Stranger. I’m aware that many of the residents might not do the walk or listen to my essay, but I believe there’s a potential in this small gift: to give without being asked to do so and without measuring or immediately knowing its effect.

Throughout the audio essay, you refer to several conceptual works by artists such as Yoko Ono’s Line Piece (1964) and stanley brouwn’s This Way Brouwn (1963), to reflect on themes of distance, direction and movement unified by the notion of creating and tracing lines (metaphorical or physical, straight or otherwise). Can you say more about how such works have influenced your thinking about your own way of moving and living in the world?

The conceptual works of Yoko Ono and stanley brouwn are often so succinct, consisting of a single sentence or gesture, yet holding the potential to suddenly turn everything upside down. In this sense, these works are a gift to the viewer/reader/recipient, but the recipient must also give something in return, using their imagination to experience the work. We don’t just look at these works in awe in a museum or gallery, we can take them with us and carry them around.

I hope to bring some magic back to the city, in a place where one wouldn’t necessarily expect it

Hoofdweg (a possible line) work in progress, featuring notes, a script and the publications In & Out of Amsterdam / Travels in Conceptual Art (MoMA, 2009) and Grapefruit (Yoko Ono, 1970 edition), image by Radna Rumping

Although I generally move from A to B in a pragmatic way, there are times when such works suddenly come to me, and carrying them with me creates a different kind of agency; a heightened awareness of possibilities and irrational desires: What if I were to walk all the way down the Hoofdweg for no reason? What if I let my hair grow, without ever stopping? These works carry a certain magic and potential and I hope to bring some of that magic back to the city, in a place where one wouldn’t necessarily expect it.

In your audio work, walking comes as naturally and effortlessly to you as growing out your hair. You also seem to place yourself in the position of the flâneuse or psychogeographer who wanders the city making observations about a changing society, especially when you speak about ‘the man with the slippers’ and dive into the history of the Hoofdweg. What is walking to you and what is the role of walking in this project?

I mainly move around through the city by bicycle, for practical reasons. I consider walking as more enjoyable, since it is slower and makes me more aware of my environment and all its details. I wouldn’t say walking comes effortlessly per se. For instance when I describe the ‘man on the slippers’, I notice how much effort it takes for him to walk, shuffling slowly over the pavement. Even in the context of walking as an artistic medium, I mainly consider my medium to be textual. Still, I see a relationship between writing and walking. When I write, I try to look at myself simultaneously as subject and object. I’m observing my thoughts while I’m writing out these thoughts, unsure of where that path will lead.

Gloria E. Anzaldúa has written wonderfully and precisely about this when describing her writing process, saying, “I am the one who writes and who is being written.” When I’m walking, I observe my surroundings and at the same time I’m also aware of my own presence in these surroundings. This is another reason why walking isn’t always effortless – it sometimes depends on whether one feels comfortable walking in certain environments and what kind of gazes one receives while walking in public space.

I was struck by the statement ‘architects with big plans seem a bit suspicious these days’. Can you share your thoughts on humans’ relationship with their built environment and your suspicions about big architectural plans, especially regarding the city of Amsterdam?

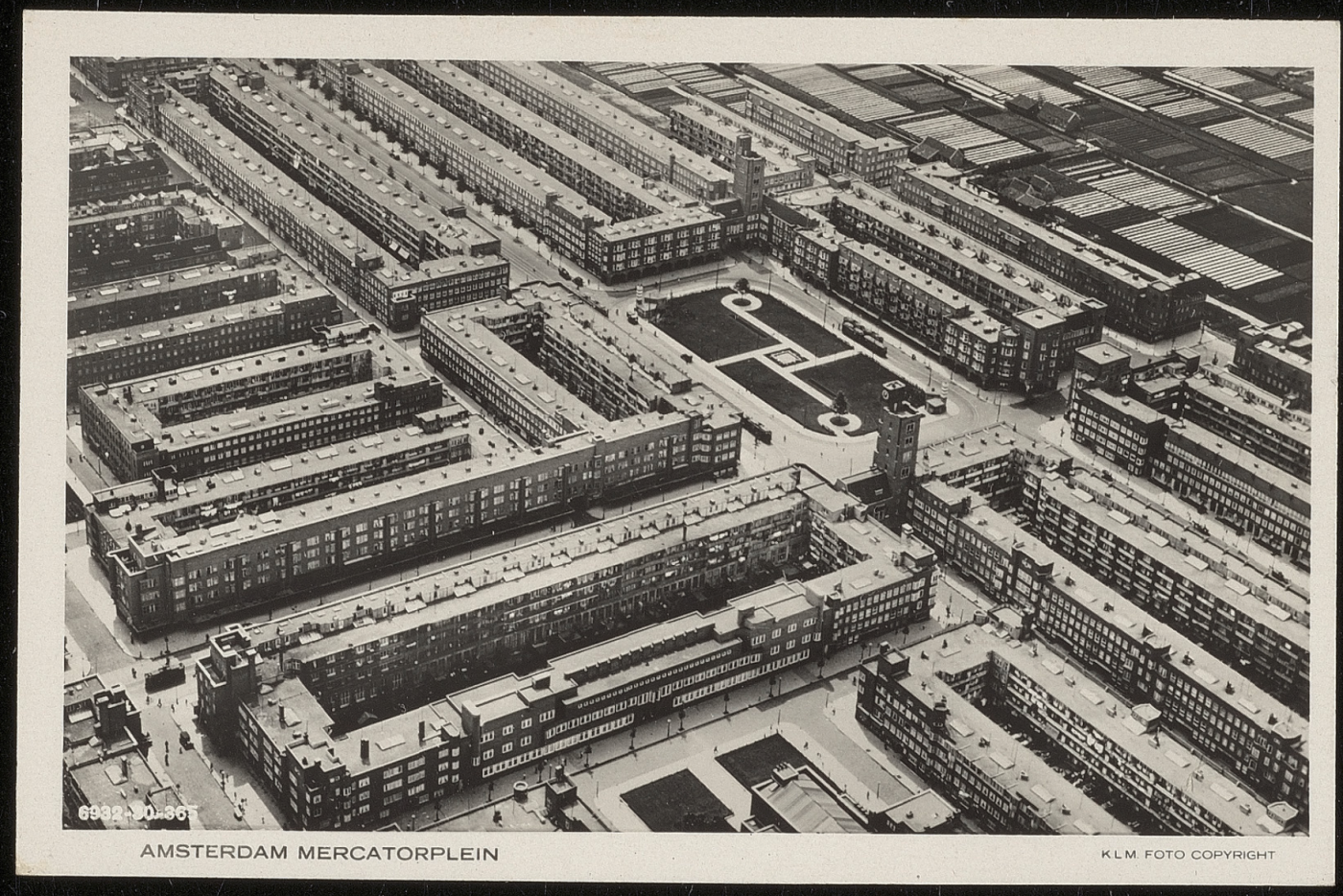

This statement is ambivalent. It has to do with a long history of city-planning up to this day. During the walk, I reflect on how the Hoofdweg was initially developed around 100 years ago, and focus especially on Hendrik Wijdeveld, the architect who also designed the stark façade of the building where I live. The surrounding neighbourhood was developed in just a few years’ time as part of the large city expansion project known as ‘Plan West’. It was a grand gesture with good intentions, a plan that was successful overall and still remains part of Amsterdam’s DNA. But of course, by now we also know of many examples of well-intended social housing projects that looked good on the drawing board but hardly took the living needs of the inhabitants into account.

Historical image of the Hoofdweg in the 1920s, image from Stadsarchief Amsterdam.

Photograph made during a walk along the Hoofdweg. Photo by Radna Rumping.

The bird’s eye view of a single architect (who in most cases happened to be white and male) became suspicious, and rightly so. Furthermore, the current strategies for city planning in Amsterdam, which claim to be more ‘bottom up’ and less ‘top down’, are often regulated by the market or by inhabitants who have the means and time to make their voices heard. Over time, many social housing units on the Hoofdweg have been sold off and in the current market, this means that the area is, for many people, no longer affordable. So, I have ambivalent feelings about both grand architectural gestures from the 1920s and the current ways of city planning.

At some point you contemplate the (lack of) visibility of female artists in the art world who have been – and sometimes still are – overlooked for far too long before achieving the recognition they deserve. Their trajectory can perhaps be considered one of the metaphorical lines that you trace through your work. Could you tell more about your perspective on this?

This reflection is based on my recent collaborations with artist Sands Murray-Wassink and If I Can’t Dance. Together we developed an archive for Sands under the name Gift Science Archive, which deals with his 25-year long artistic practice. Sands, an artist who is indebted to various forms of intersectional feminist and queer art, had moments where his partner Robin was literally his only audience. It has been moving and motivating to speak with him about maintaining a practice that has sometimes been completely overlooked, and what it means to be ‘ahead of your time’, as is often said these days of female artists who get their first significant solo exhibition when they’re 70+ years old.

I symbolically relate the form of a ‘long line’ to a long career and the fact that it’s never too late to become an artist (something I also like to keep in mind for myself). The Hoofdweg might look like a straight road, but life moves in its own irregular ways – people can turn around, take a side street, re-emerge, or simply view the road as a very long run-up to a diving board from which to jump to elsewhere.

Characteristic for Welcome Stranger is that the art can be seen in or around the private residences of artists. Due to the pandemic, the focus has temporarily shifted outside. Participating artists in this second edition are Esther Tielemans (Maarten Harpertszoon Trompstraat), Kévin Bray (Woutertje Pietersestraat), Radna Rumping (Hoofdweg) and Lily van der Stokker (Valeriusstraat).

For more information on the other artworks that are part of Welcome Stranger and on the overall project, see the website.

Manuela Zammit

is a writer and researcher from Malta