An urgent attempt – Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism Colonialism at the Stedelijk

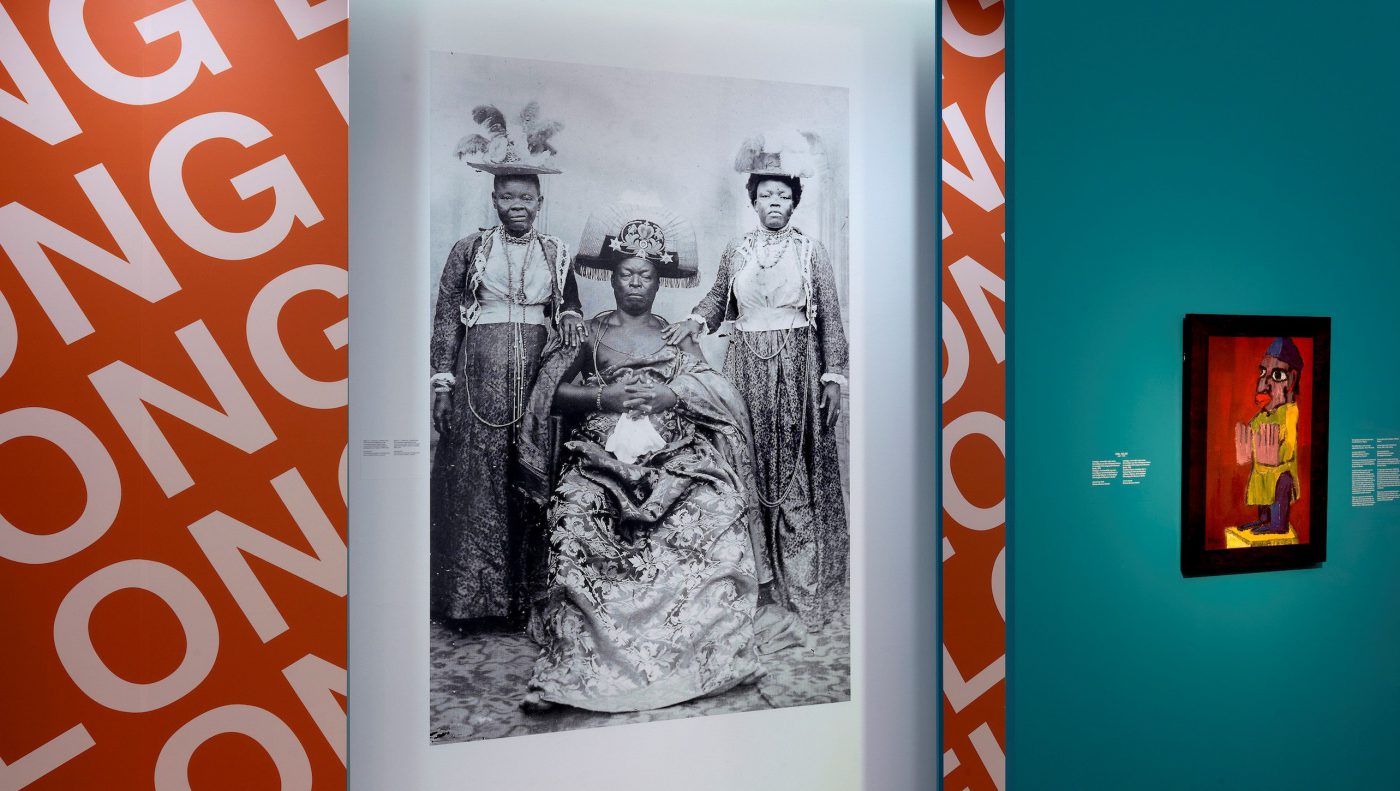

Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism Colonialism at the Stedelijk Museum tells a broader, darker story about two masters of modern art. It attempts to break free from the persuasive grip of art history and bridge the colonial divide between “art” and “ethnographic objects”. All of which Hannah Vollam deems necessary if the museum wishes to be relevant or inclusive.

This exhibition is a definite step away from the familiar for the Stedelijk Museum. The lives and works of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde, two important artists in the museum’s own collection, are placed within the context of German imperialism and colonialism. They are viewed not as great wonders or pinnacles of art history (as would be the norm), but from a highly critical, “postcolonial” perspective. A broader, darker story is told. The ethics and aesthetics of their practices are scrutinised and called into question, and major cracks in the well-known glorified narratives of modern art become clear.

Artworks by Kirchner and Nolde are shown alongside historical documentation, photographs, and “ethnographic objects”, showing how “masterpieces” of German Expressionism really rely on the appropriation, exoticisation, and exploitation of non-Western people and artistic traditions. That is: the very cultures that were othered, subjugated, and destroyed by the colonial system. The Stedelijk being the Stedelijk (a high-profile art museum, where you might imagine breaking with the status quo is difficult) I expected questions of inspiration and fascination versus appropriation to land more cautiously than they do. Thankfully, there is little room for ambiguity. Wall-texts are overly frequent and long, but they do mostly take a position. There are definitely more answers than questions, making the narrative feel determined — surely a good thing, if we are ever going to break free of the myths of modernity.

[blockquote]The exhibition asks us to see from a perspective that is contradictory to what most people have been taught. So we are challenged to take off our rose-tinted glasses and question ourselves

Installation view Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism. Colonialism. Photo: Gert-Jan van Rooij

Installation view Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism. Colonialism. Photo: Gert-Jan van Rooij © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Installation view Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism. Colonialism. Photo: Gert-Jan van Rooij

Condemnations are sometimes subtle, but there are moments where subtleties seem to be pushed into the territory of indictments. In the rooms that critique the artists use of child models, the wall-text reads, “the frequently erotic poses reveal, at the very least, an abuse of power in the name of art”. Artist as abuser. Later, Nolde’s portraits of people from Papua New Guinea are described as part of his mission to “study the population’s racial characteristics”. The artworks and their maker are directly connected to the pseudoscientific racist theories that underpin colonialism. Artist as coloniser. The artists are respectfully de-throned.

To implicate these artists, to burst their bubble, implicates us and bursts our bubble too. The exhibition asks us to see from a perspective that is contradictory to what most people have been taught. So we are challenged to take off our rose-tinted glasses and question ourselves. I found myself shifting between different ways of thinking and seeing. I’ve been taught to see Kirchner and Nolde’s bold, sensual works as impressive and beautiful, so I was often drawn to simply admiring them. Catching myself with my rose-tinted glasses on, I would then consciously work to shift into a more critical frame of mind, asking myself why it is that the maker of a beautiful Cameroonian “ko’oh” (carved stool) — part of Kirchner’s own art collection, often used as a prop for his female nudes — is not worth remembering, while Kirchner himself is worthy of glory.

Interviews with external experts are shown on screens throughout the space. These voices definitely give weight to the curatorial agenda, but also push the criticality meter even higher, and often beyond Kirchner and Nolde themselves. On a small screen mid-way through the exhibition, Andy Zimmerman (professor of German history at George Washington University) discusses the art versus ethnographic museum divide, this being a key manifestation of colonial hierarchy and racism.

Why are artworks from West-Africa considered “ethnographic objects”, while Kirchner and Nolde’s creations are defined as “art”?

Installation view Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism. Colonialism. Photo: Gert-Jan van Rooij © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Installation view Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism. Colonialism. Photo: Gert-Jan van Rooij

There is far too much information for regular museum visitors to take in, so I wouldn’t be surprised if these interviews are overlooked. I hope that they aren’t, because they are an important addition to the museum voice. Zimmerman’s words pushed me to think in a new way about why artworks from West-Africa are considered “ethnographic objects”, while Kirchner and Nolde’s creations are defined as “art”. And with questions like this in mind, viewing these modern artworks side-by-side with the objects and artworks they are so indebted to begins to feel like a symbolic bridging of colonial divides.

The exhibition is challenging. Recent reviews in Het Parool and De Volkskrant demonstrate this. Edo Dijksterhuis and Rutger Pontzen seem to center on a dislike for the compelling right-wrong curatorial agenda, the sidelining of art and the experience of it, and a general defensiveness of the artists. There are some who would rather not take off the rose-tinted glasses and connect modernism with colonialism. To me, this exhibition is overly dense, overly explanatory, and predetermined, making it feel fairly static, but it is also an urgent attempt to tell new stories about art from the past; to break free from the persuasive grip of art history; and to bridge colonial divides (art history/anthropology, art museum/ethnographic museum). All of which are necessary if museums wish to be relevant or inclusive. Het Parool stated that this exhibition marks the “beginning of the end of the art museum”. To me, it shows the possibility of a liberated one.

Installation view Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism. Colonialism. Photo: Gert-Jan van Rooij © Nolde Stiftung Seebüll

Kirchner and Nolde: Expressionism Colonialism at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam is on view until the 5th of December

Hannah Vollam

is schrijver