Left:Tom Henderson Chief ‘Nakwaxda’xw First Nation Filmstill How A People Live, Lisa Jackson (Dir.) © Gwa’sala and ‘Nakwaxda’xw First Nations 2013. Right: Caroline Monnet Mobilize, 2015 Single Channel Video 3 minuten, Filmstill, National film board of Canada © Caroline Monnet

Landscapes of perception – Magnetic North at the Kunsthal

The exhibition Magnetic North at the Kunsthal contrasts vivid images of fallen red leaves, sunlight on fresh snow, or a lone canoe drifting along a forest-lined creek with Indigenous understandings of the same land. Colin Keays on a curatorial attempt to critically reframe Canadian nationhood.

When imagining Canada, even those who haven’t set foot there might immediately conjure vivid images of fallen red leaves, sunlight on fresh snow, or a lone canoe drifting along a forest-lined creek. This vision of Canada is so firmly etched into cultural imagination that the idea of Canada itself cannot be uncoupled from these images of wilderness.

A.Y. Jackson, Lake Superior Country, 1924, oil on canvas, 117 x 148 cm, Donated by mr. S. Walter Stewart McMichael Canadian Art Collection 1968.8.26 c/o Pictoright Amsterdam 2021.

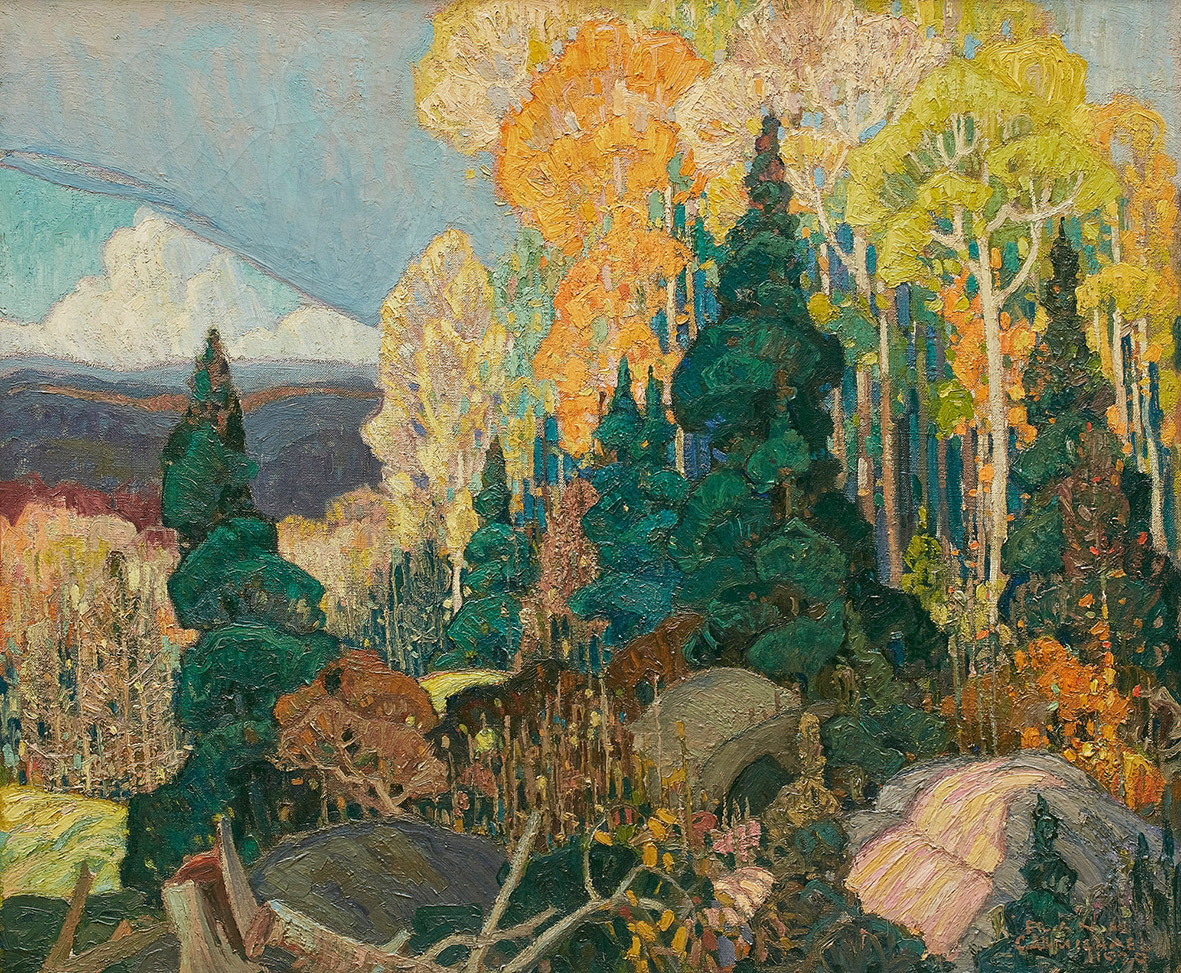

Much of this imagery was cemented by the Group of Seven and their contemporaries – an artistic collective operating during the early twentieth century that sought to find a new style of painting to truly reflect the Canadian wilderness in a way that distanced itself from the European tradition of landscape painting. Central to this was the artists’ relationship to a sense of place. The way that Tom Thompson created oil sketches (1912–1917) on location in Northern Ontario, for example, allowed for a dynamic approach in which vivid colours, textures and brushwork truly brought the breathtaking seasonal changes to life. Meanwhile, the heavily stylised depictions of the monumental Rocky Mountains and northern icebergs by Lawren Harris brought a pioneering modernist approach to the remote landscapes.

Tom Thomson, Claremont, Northern Lights, Ca. 1916-1917, oil on wood. The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, acquired by A. Sidney Dawes Fund Foto MMFA, Jean-François Brière

Lawren S. Harris, Icebergs, Davis Strait, 1930, oil on canvas, 21.9 x 152.4 cm Donated by mr. en mevr. H. Spencer Clark McMichael Canadian Art Collection 1971.17 © Family of Lawren S. Harris.

What’s striking about the exhibition Magnetic North: Imagining Canada in Painting 1910–40, currently on display at the Kunsthal in Rotterdam after premiering at Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, is that rather than focusing on the quality of the paintings themselves (many being introduced to a European audience for the first time), the curatorial approach instead looks towards how this artistic movement came to shape the cultural perception of Canadian nationhood. To this end, the exhibition is interspersed with contemporary audiovisual works that reveal and contextualise how the artists’ perspectives contrast with Indigenous understandings of the same land.

Installation view Magnetic North at Kunsthal Rotterdam. Photo: Marco De Swart.

A.Y. Jackson, Terre Sauvage, 1913, oil on canvas, 128.8 x 154.4 cm. Acquired by 1936 National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Foto: NGC

Upon entering the exhibition, I am handed a leaflet that contains a glossary explaining some important historical context relating to the First Nations of the land we now refer to as Canada. From the outset, this charges the exhibition with a sense of urgency. To view a display of nation-defining artworks without acknowledging the shameful legacy of the country’s settler-colonialism would be truly crass, especially against the contemporary backdrop of the recent discoveries of mass graves of hundreds of child victims of the residential school system, the ongoing epidemic of missing Indigenous women, and the gas pipeline being built through ancestral Wet’suwet’en territory.

Consequently, the curatorial texts allude towards the idea that the unpopulated wilderness or ‘terra nullius’ depicted in many of the paintings could easily be weaponized in the cultural genocide of Canada’s Indigenous population, and that many of the artists were instrumental in perpetuating a narrative that glossed over the industrialised logging, mining and displacement of communities. A central friction at the heart of this exhibition therefore seems to be: is it possible to appreciate the beauty of these paintings and the land that they depict without a sense of guilt?

Undeniably, there is an urgent place for decolonial critique within art institutions. As museums finally begin to reckon with the ways that the provenance of art collections is intertwined with colonial violence and extraction, a critical revision of the work on display is long overdue. Elsewhere in the Netherlands, the Amsterdam Museum has stopped referring to the Dutch colonial period as the ‘Golden Age’, the Rijksmuseum has re-evaluated its collection through narratives around slavery, while Kunstinstituut Melly – just a stone’s throw from Rotterdam’s Kunsthal – finally changed its name entirely in order to distance itself from the eponymous colonial naval officer Witte de With.

It is exactly for this reason that the framing of Magnetic North sits a little uneasily. Are the curators positioning the work in this way because of a genuine desire to centre Indigenous perspectives from the territories we now call Canada, or are they simply trying to fit within the current zeitgeist in order to remain culturally relevant? While more nuanced and in-depth analysis is included in the accompanying catalogue, many of the exhibition wall-texts come across as a little opportunistic or even contrived in a way that patronises and potentially alienates certain audiences. Provocative opening phrases such as ‘All official members of the Group of Seven were white men,’ give valid critique that unfortunately comes across as performative, considering the gendered component to their work is not given much scrutiny beyond that.

Installation view Magnetic North at Kunsthal Rotterdam. Photo: Marco De Swart.

The inclusion of two particular pieces of work does stand out as a genuine attempt to address some of these contradictions. Anishinaabe filmmaker Lisa Jackson’s documentary How a People Live (2013) gives important context to the forced relocation of Indigenous communities that took place well into the twentieth century, highlighting the significance of ancestral connections to land. This contrasts with the approach of the painters on display, who seemed to depict a newly ‘discovered’ wilderness. Similarly, Algonquin-French artist Caroline Monnet’s video work Mobilize (2015) collages archival footage, taking the viewer on a journey from Indigenous communities in the far north to the urban south. Cut quickly and set to the fast-paced soundtrack of Inuk throat singer Tanya Tagaq, the work alludes to the industrialisation and urbanisation of Canada, and the place of Indigenous populations in this context. The ways that these two works sit in juxtaposition to the rest of the exhibition hopefully does offer the viewer some of their own tools to re-evaluate the context of the paintings on display. Nonetheless, it is worth considering whether having only two works by Indigenous filmmakers contrasted with over eighty paintings and thirty sketches by white artists only reaffirms the Eurocentric narrative that the exhibition claims to disrupt.

Franklin Carmichael, Autumn Hillside, 1920, oil on canvas, 76 x 91.4 cm. Donated by the J.S. McLean Collection, Toronto, 1969, donated by the Ontario Heritage Foundation, 1988 © Art Gallery of Ontario L69.16

This leads to an important question: is a blockbuster art exhibition in Western Europe sufficiently equipped to deal with sensitive themes around First Nations land sovereignty and environmental destruction? Perhaps not, considering it chooses to primarily cover these issues through the work of a select group of non-Indigenous artists when so many fantastic First Nations artists could have been included. One can appreciate the intent behind the ways Magnetic North critically re-evaluates the work of Canadian modernist painters to open up important conversations about the instrumentalisation of art in the formation of a fledgling national identity. However, an art exhibition that only takes Indigenous perspectives as an anecdotal counterpoint to the main work on display – rather than one that centres them altogether – can never truly resolve the tension it seeks to surface.

Magnetic North will be on view at the Kunsthal in Rotterdam until January 9th, 2022. For more information, see the website of the Kunsthal.

Colin Keays

is spatial designer en researcher