Arturo Kameya, ‘Drylands’, Dordrechts Museum. Photo LNDWstudio

Distant childhood memories in dusty pinks and sandy yellows – Arturo Kameya’s ‘Drylands’ at Dordrechts Museum

Entering Arturo Kameya’s exhibition space at Dordrechts Museum feels little like arriving someplace warm, and that’s not just because of the show’s title – Drylands. Using sandy yellows, dusty pinks and pale greens, the artist invites visitors to walk around in childhood memories of his native land Peru, plastic cockroaches humming in the distance.

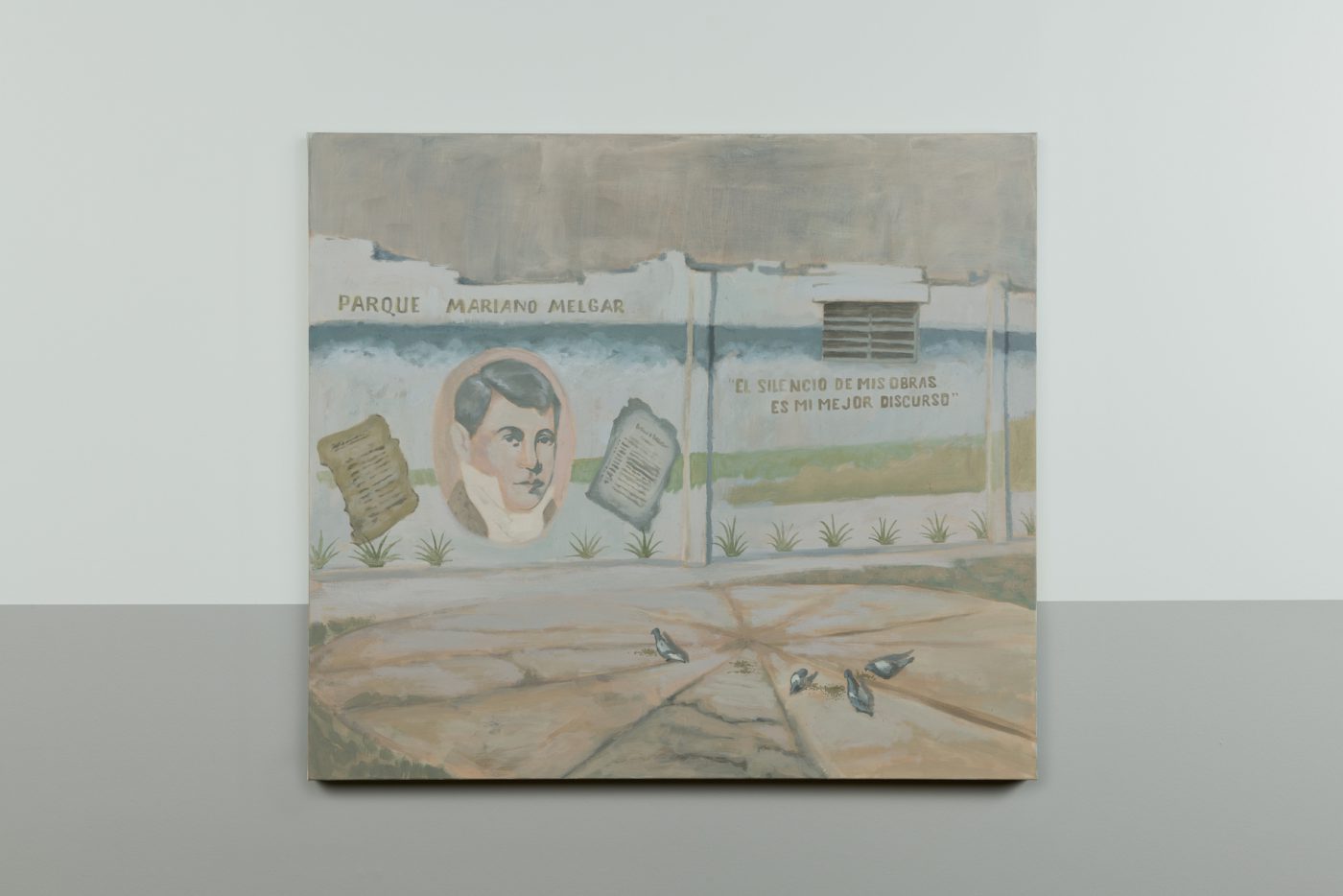

It took me a moment to realise that I had encountered Arturo Kameya’s work before. It was the little plastic cockroaches nonchalantly hanging out on miniature clay chairs, that made me recall seeing it at the Rijksakademie’s Open Studios in Amsterdam last year. Now that I thought about it, Kameya’s cockroaches are the only ones I have seen in almost two years living in the Netherlands. All my memories of these critters come from hot and humid Maltese summers, when there’s an abundance of them crawling about. In fact, entering the exhibition space did feel a little like arriving someplace warm, and it was not just the show’s title – Drylands – that pre-empted it. Kameya’s paintings and installations, comprising both existing and newly-commissioned works for his first solo museum exhibition in the Netherlands, are characterised by a ‘muted’ palette of sandy yellows, cloudy greys, dusty pinks and pale greens that gives them a weathered appearance – as if they had been left outside to fade away under the scorching hot sun.

[blockquote]The works have a weathered appearance – as if they had been left outside to fade away under the scorching hot sun

Arturo Kameya, 'Drylands', Dordrechts Museum. Photo LNDWstudio

Arturo Kameya, 'Drylands', Dordrechts Museum. Photo LNDWstudio

Arturo Kameya, 'Drylands', Dordrechts Museum. Photo LNDWstudio

Yet despite the lulling effect of the calming tones and the ongoing humming sound in the space, the room is anything but static and arid. Kameya turns own childhood memories of growing up in his native Peru and sights from Lima’s streets, into dynamic arrangements that function well both as self-contained units and as a combined whole. His pieces are animated by a systems aesthetic, the interplay between two and three dimensionalities, and a touch of magical realism that pervades his paintings. A mechanical fish made out of a drinking can swims in circles in a tank, and two ceramic dog heads with tripods for bodies face each other while actively foaming at the mouth. Further ahead, water slowly drips at steady intervals from the nose of a cat sculpture placed at the top of a ladder. The drops land on its kitten’s mouth, playfully strewn on its back on the floor beneath. The cat is the artist’s childhood pet named Pinky, which decided to go and live on the family home’s roof, had kittens, and started dropping them back into the house one by one so that the humans could care for her babies.

Kameya does not conceal the simple mechanics that bring the sculptures to life, but he does skilfully incorporate them in a way that they can easily ‘hide themselves’ and be forgotten by the viewer. For instance, the little motor directing the drinking can-fish is attached where the fish’s fin would otherwise be, and can, in fact, be imagined as such. The winding pipe connected to Pinky the cat on one end and to multiple water sources on the other, is visible as an aesthetic component of the work, but is also transparent enough so as to conveniently disappear from the viewer’s consciousness.

Despite the lulling effect of the calming tones and the ongoing humming sound in the space, the room is anything but static and arid

Arturo Kameya, 'Drylands', Dordrechts Museum. Photo LNDWstudio

Arturo Kameya, 'Drylands', Dordrechts Museum. Photo LNDWstudio

This had an interesting effect on my experience of the works, leading to two possible readings of the exhibition. At certain moments, with a systems approach in mind and the transparent pipe clearly within my sight, I read the works as reflecting on how all life on Earth is a finite, physical system in which all entities are interdependent. This reading fits with the idea of Drylands articulated by the artist as the struggle to live in barren environments and the negotiations necessary for life in all its forms to go on. In light of this notion, I thought about Pinky’s dependence on her human owners for food, water and shelter. A potted plant (of which many several depictions were present in the room) has a whole root system that helps it stay alive, but even this needs to be watered by humans or the rain every now and then. In turn, human life depends on access to clean water, food and a favourable climate, while quality of life is certainly improved thanks to companion species such as cats, dogs and even plants.

In other instances, I let my imagination take over and come up with possible narratives for the whimsical scenes and installations that opened themselves up for speculation. Several two-dimensional painted surfaces looked misleadingly three-dimensional, like the number of ‘clothing items’ on the floor in various spots around the room. I wondered who these might have belonged to and why they left them behind like that, seemingly in a hurry. Other pieces were even propped upright and combined with actual solid objects, giving off the feeling of having walked into a life-size pop-up storybook where the distinction between reality and imagination quickly starts getting blurred. On one of the walls, a captivating diptych showed, on one side, two faceless human figures dressed up as mice (or two mice that had just been transformed into humans) pretending to chase each other around their domestic setting, and, on the other, a black cat with hollow eyes looking suggestively towards the viewer. I was not sure what to make of it, but I was intrigued. Meanwhile, the cockroaches were having a mysterious congregation of their own. What might they have to tell each other on such a Sunday morning?

I left the space feeling like I had just walked out of someone else’s curious dream

Arturo Kameya, 'Drylands', Dordrechts Museum. Photo LNDWstudio

Arturo Kameya, 'Drylands', Dordrechts Museum. Photo LNDWstudio

While the exhibition itself spans only one room, there is certainly no shortage of imaginative associations to be made and little details waiting to surprise the observant eye. I left the space feeling like I had just walked out of someone else’s curious dream. In a way, I suppose I had. Recreating distant childhood memories of one’s own native land after living elsewhere for so long, must have some dreamlike qualities to it. Not to mention that art, like dreams, lends itself well to interpretation.

Drylands runs until Sunday May 8 at the Dordrechts Museum

Manuela Zammit

is a writer and researcher from Malta