No Master Territories – Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image. Exhibition view © Studio Bowie / HKW

Feminism through film – No Master Territories at HKW, Berlin

No Master Territories at Haus der Kulturen Welt (Berlin) reconsiders filmworks from the past century in an attempt to retrack the course and potential of what a global feminist agenda is. The exhibition shares an abundance of films made by women in the 70s-90s, but still manages to fix its attention to individual subjects and their experiences.

Haus der Kulturen Welt (HKW) faces the Tiergarten to its front, backing onto the river Spree behind in Europacity: a neighbourhood of widely dispersed museums, government buildings and diplomat homes in central Berlin; with vast, flat, well-lit green spaces, separated by often-empty roads. The area undefined, malleable.

No Master Territories, curated by Erika Balsom and Hila Peleg, is an ambitious reconsideration of films made by women in the 70s-90s. Balsom and Peleg’s intentions are twofold: firstly, they want to highlight this era of women’s liberation as a primetime in women’s filmmaking. Secondly, through resurfacing existing works in this extensive catalogue of visual art, No Master Territories channels a global feminist agenda that does not adopt the single issue politics that still dominate feminism in the geopolitical west.

No Master Territories - Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image. Exhibition view © Studio Bowie / HKW

The primary gallery space is a forest of screens with selected photography and reprints of essays, journals and zines, peppered along the walls. In the basement is a cinema with a repeating weekly schedule of further filmwork and upstairs a small terrace of resources that serves as a library to spend time with the written works by Alice Walker, Etel Adnan, Angela Davis and Assia Djebar, among others.

The films are decentralised, scattered throughout the space. As I look at one screen, my eyes have to hold back from darting to six other screens in my periphery

No Master Territories - Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image. Exhibition view © Studio Bowie / HKW

No Master Territories - Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image. Exhibition view © Studio Bowie / HKW

The films are decentralised, scattered throughout the space. As I look at one screen, my eyes have to hold back from darting to six other screens in my periphery. Similarly, the films in the cinema are showcased in doubles, encouraging the viewer to never single out one work or depicted experience. This can undoubtedly be overwhelming as the exhibition grapples with a huge pool of film archive; to see all of these works in their entirety is incomprehensible, despite the ticket guaranteeing two entries. However, the quietness of Europacity often permeates HKW: it is populous but not busy, with space to ponder the works outside of the gallery spaces.

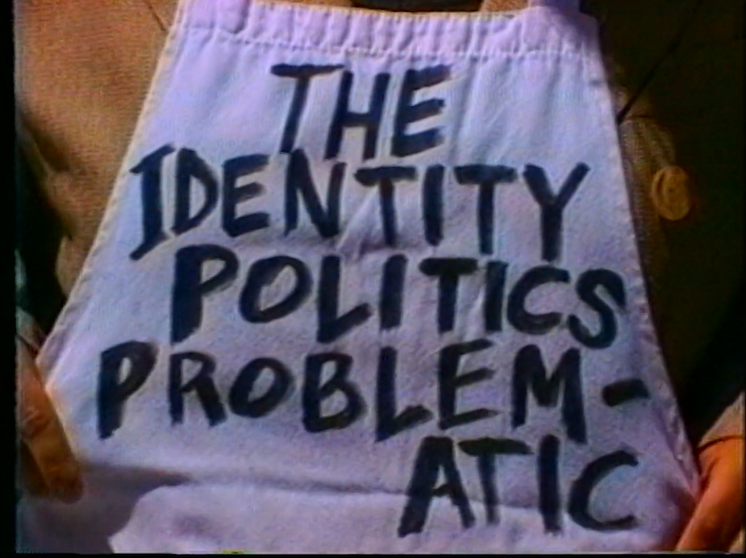

Paper Tiger TV, from Sisterhood™: Hyping the Female Market (1993), film still, courtesy Paper Tiger TV

The content of the exhibition sees recurring concerns and themes develop. Sexual exploration, working conditions, invisible labour, exclusion, displacement and consumerism’s impacts on women’s rights crop up throughout: nightcleaners in London organising for better working conditions in Nightcleaners (1975, UK), critique on the explosion of advertising geared at women in the latter 20th century Sisterhood™TM: Hyping the Female Market (1993, USA). Miss Universo en el Perú (1982, Peru) by Group Chaski shows women protesting over being exploited in their work and their tax money being spent on Miss Universe contestants to be put up in hotels, while others are living in poverty and “giving birth on the ground”.

The content of the exhibition sees recurring concerns and themes develop: sexual exploration, working conditions, invisible labour, exclusion, displacement and consumerism’s impacts on women’s rights crop up throughout

Han Ok-hee, Untitled 77-A (1977), film still, Courtesy of Asia Culture Center (ACC)

Helena Amiradżibi, Kobieta to słaba istota (The Weak Woman, 1967), film still, courtesy of Documentary and Feature Film Studios, Warsaw, Poland

24 Godziny Jadwigi L. (1967, Poland) by Krystyna Gryczelowska shows a mother living two days in one. The first working the night shift in a factory making wire. She then makes her way home bumping into others commuting the opposite direction, towards work. Rather than sleep, she starts her second day of childcare and housework, setting an alarm for what we know to be an insufficient amount of sleep, before returning to prepare dinner for the family. Next to this screen, Ana Victoria Jiminez’s photographs of close up hands in Cuaderno de tareas (1978-81, Mexico) show the often unseen endless labour and care that is performed: food preparation, the sewing and mending of clothes, toilet cleaning, plants being watered and pruned. The inclusion of photography often relates to the film surrounding it and is better positioned than the reprints of essays and zine excerpts that can be difficult to adjust the eyes to.

Nalini Malani, Onanism (1969), film still, copyright Nalini Malani

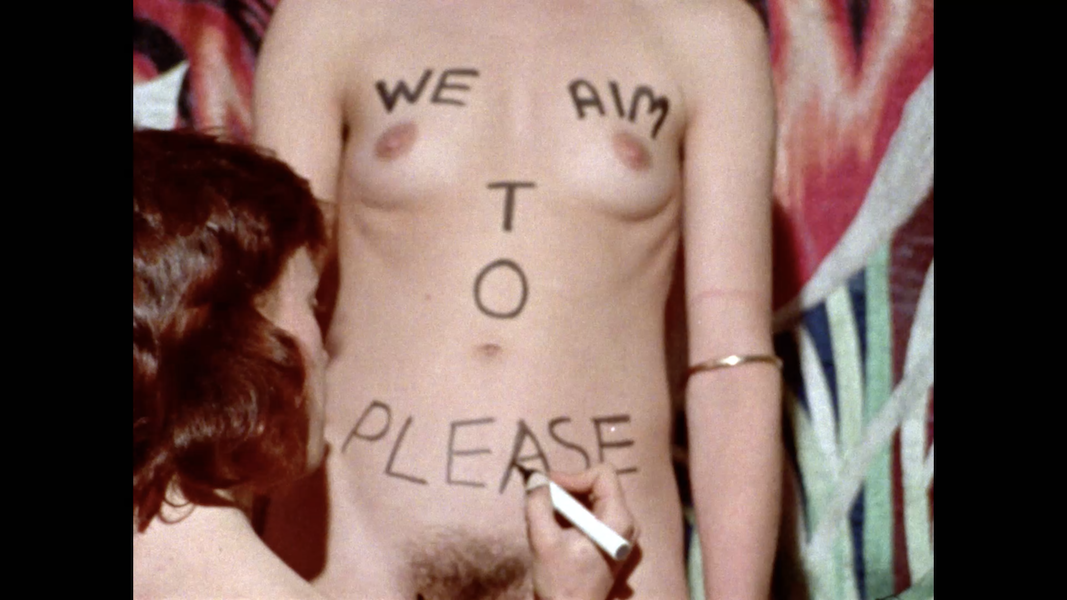

There are several works documenting examinations of sexuality in women’s film. Nalini Malani’s Onanism (1969, India) is an ambiguous four minute short of a woman moving a sheet of fabric between her legs. Alice Anne Parker’s Near the Big Chakra (1971, USA) shows 38 vulvas close up. Other films depict sex parties. While this portion of works may feel of a bygone time in its subject; it does reposition the depictions of female sexuality navigated in film. Sexual liberation is often still recollected as a western movement that took place to be emulated elsewhere, rather than acknowledging the many sexual liberation movements of past and present that root themselves in their own cultural and geographical histories.

Sexual liberation is often still recollected as a western movement that took place to be emulated elsewhere, rather than acknowledging the many sexual liberation movements of past and present that root themselves in their own cultural and geographical histories

Robin Laurie & Margot Nash, We Aim to Please (1976), film still, copyright Robin Laurie & Margot Nash

The cinema schedule includes eight films that form a commissioned series As Women See It of thirty minute shorts, two of which are Safi Faye’s Selbé et tant d’autres (1982, Senegal) and Atteyat Al-Abnoudy Permissible Dreams (1984, Egypt). The first follows Selbé in Senegal, as she works long hours to provide for her family surrounded by other women doing the same. The husbands are absent, occasionally shown gathering in brief shots; they are away looking for work. Selbé’s daughter asks if she can go to school but is told she must help her mother with the work. In Permissible Dreams, Oum Said residing north of Suez city, displaced from the Six Day War, describes a missile hitting her olive basket, and never seeing the perpetrator of who displaced her. Her and her husband work in agriculture, but she does most of the work. Mona, one of Oum’s daughters, is the only daughter of the 48 girls within her larger family to go to school.

Lettre de Beyrouth (1978, Lebanon) by Jocelyne Saab, shows Saab trying to travel from one side of Beirut to the other, primarily by bus. The narration written by Etel Adnan, recounts schooling being delayed for two months because of the civil war. One student had to stop attending their school because the bus stopped passing the demarcation line, but the American University got to remain open and even held a rock concert. Saab passes ten checkpoints on her journey. The narrator gets dizzy from the many borders and many languages spoken within a tight geographical space.

In Aujourd’hui dis-moi (1980, France) Chantal Akerman interviews grandmothers in Paris who survived the Holocaust. During one interview, Akerman is sat across the dining table, occasionally nibbling on the array of baked goods in front of her. The grandmother recounts losing her family, having to leave Warsaw for Paris. She sings Jewish folklore songs and imparts on Akerman the principles her grandma would share with her as she went to sleep each night as a child: “they return sooner or later, what has been sewn”. They then proceed to the sofa to watch a film together.

70% of the international working class today is women. No Master Territories proposes the need for these womens’ experiences to be at the forefront of a decolonial feminist agenda

70% of the international working class today is women. Yet the dominating images that depict this majority is that of men. No Master Territories proposes the need for these womens’ experiences to be at the forefront of a decolonial feminist agenda. This abundance of film tenderly fixes its attention to individual subjects and their experiences.

This summer has seen German art happenings navigating long term decolonial art engagement with Documenta 15 and the 12th Berlin Biennale, through uprooting the way institutions select and present art. No Master Territories contributes to this canon through reconsiderations of works from the past century in an attempt to retrack the course and potential of what a global feminist agenda is. The curators ensure to forgo any attempt to convey analysis or trajectories onto films. The focus lies in an array of individual experiences being centred, shared again, for reminders of the visual histories that already exist to learn from.

No Master Territories is on view until the 28th of August, 2022, at Haus der Kulturen der Welt

Sophie van Well Groeneveld

is a writer