Introductory presentation by Josien Pieterse, director of Framer Framed. Photo: Ju-An Hsieh

Reflecting on documenta fifteen: On the threshold of revolution?

The symposium (un)Common Grounds: Reflecting on documenta fifteen provided insight into the aftermath of documenta 15 (d15), at least from the perspective of its curators, those directly involved and those who champion it. Jack Segbars visited the symposium and reflects critically on the aftermath and legacies of d15.

The symposium was held over the course of two days in Amsterdam, at Framer Framed and the Trippenhuis, a venue of the Akademie van Kunsten, who organized it in cooperation with the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven. In four panels and an open conversation with participants online and in-person, d15’s tumultuous reception, the proceedings concerning accusations of antisemitism, and the critical importance of the exhibition as a whole were discussed. On the first day, the panels were interspersed with a musical performance by music collective PALACE OF FLOWING WATER, followed by the screening of two films from the Tokyo Reels program, which caused controversy when it was organized at d15.

Alexander Supartono. Photo: Ju-An Hsieh

Participants of the symposium ranged from artists and organizers who were directly involved in d15, to academics reflecting on related subjects. Several representatives of organizations presenting at d15 were also present, such as Mitchell Esajas from The Black Archives, Yazan Khalili from The Question of Funding, Alexander Supartono from Taring Padi and Eszter Szakács from the OFF-Biennale Budapest. From d15’s artistic team, ruangrupa, Ade Darmewan and Indra Ameng were present, as well as Charles Esche, who was part of d15’s finding committee, and Lara Khaldi and Gertrude Flentge from the documenta organization. The panels were moderated by Kerstin Winking, David Duindam and Wayne Modest, among others. Both venues were well-attended, and the audience was invited to participate in the ensuing discussions. The symposium’s aim was stated to reflect more broadly on issues of coloniality, capitalism, racism and patriarchal structures, issues that were also addressed at d15. The symposium took on a methodology of open conversation, or lumbung, which was also one of the main curatorial concepts of d15. Lumbung is an Indonesian concept that literally translates to ‘rice shed’. It represents an economical model that ensures the equal and dialogue-based distribution of resources, as well as a sustainable form of production that stands in stark contrast to the western capitalist system.

As has been discussed extensively in many reviews and comments in mostly the German media but also internationally,[1] this edition of documenta was heavily critiqued for its curatorial model, for how it failed to contain supposedly antisemitic imagery, and subsequently and more pertinently in the end, for how the accusations of antisemitism were handled within and by the organization. The central criticisms voiced in the public discussions centered around the absence of curatorial clarity, the application of overly anti-western and decolonial rhetoric, and that too little effort was made to introduce and explicate sometimes ethically challenging topics to the audience. With this in mind, the symposium provided a sort of free-haven, far away from the aggressively critical reception of d15 in Germany, while also tentatively building towards some sort of interpretative archive of the exhibition. Even before the official ending of d15, the symposium in Amsterdam provided a moment of reflection on what had been achieved, what might have been missed, and on how to proceed.

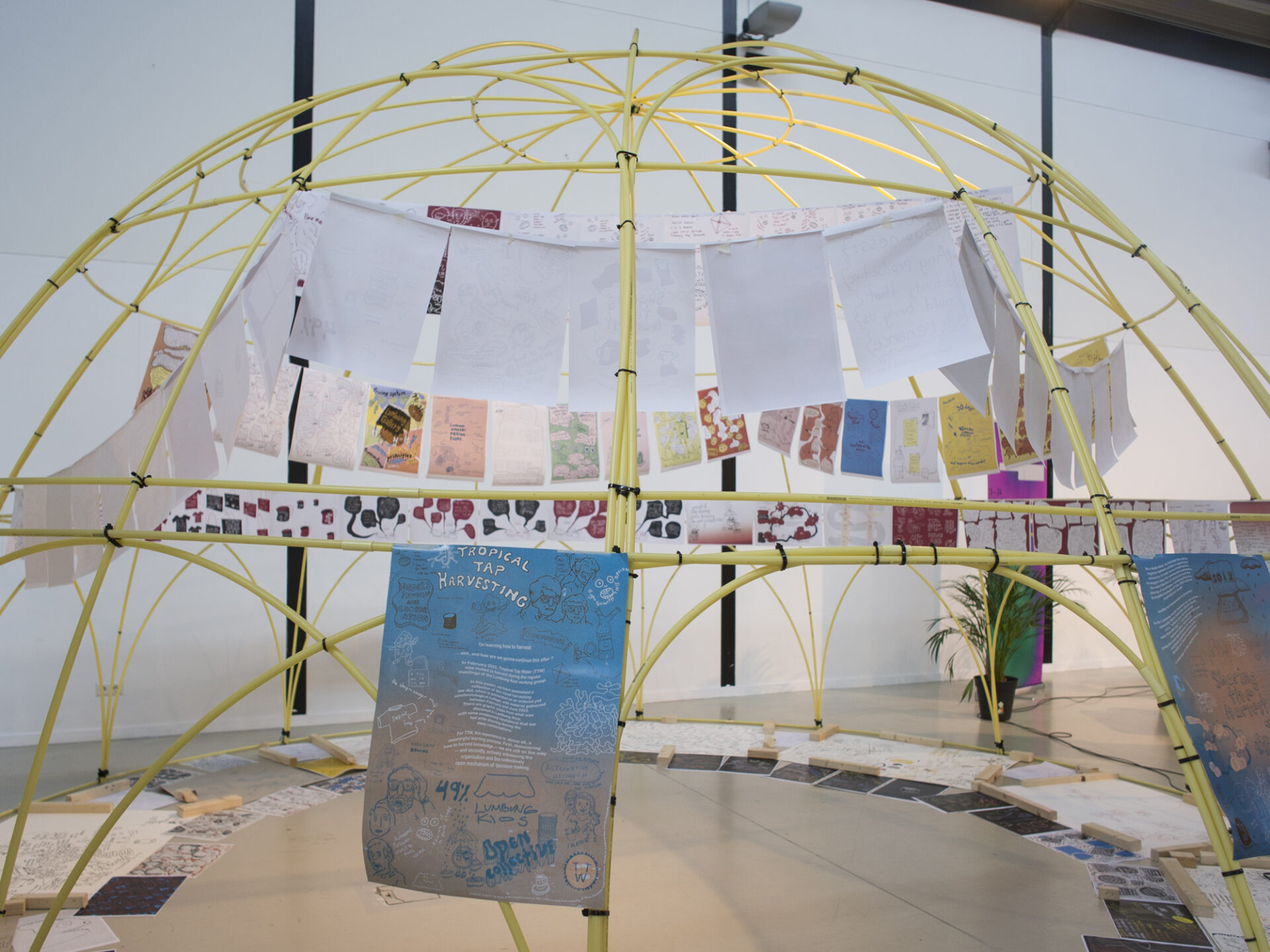

Installation for performance of The Palace of Flowing Water. Photo: Ju-An Hsieh

Day 1: An opening for discussion

The first panel of the symposium, titled Politics of Memory in a Changing State: documenta fifteen, Colonial Legacies and Entangled Histories, tackled one of the earliest and most pervasive upheavals concerning antisemitism at d15: the discovery of a supposedly antisemitic caricature in a banner titled People’s Justice by Indonesian art collective Taring Padi. The discovery of this image was deemed by some German media absolute proof of the antisemitic tendencies of the Indonesian collective and lead to calls for the expulsion of Taring Padi from d15. Both the German and Israeli governments condemned the banner and the mayor of Kassel even ordered the banner to be taken down immediately. Claudio Roth, Germany’s commissioner for culture, demanded that those responsible would face consequences. A few weeks later, director of documenta, Sabine Schormann, resigned. All attempts towards an open dialogue were met with hostility and mutual misunderstanding.

Although ruangrupa apologized for the imagery and swiftly removed the banner, they also demanded recognition of the cultural context from which the imagery originated. At the symposium, panelist Esther Captain, expert on the history of Indonesia in the colonial context, traced the specific images that were the subject of debate back to the Indonesian context in which they were produced. She explained that similar imagery was first introduced by the Japanese forces occupying Indonesia who, as axis partners with Nazi Germany, introduced anti-Jewish politics and antisemitic propaganda. The Dutch colonial period prior to that also introduced anti-Jewish sentiments via the NSB, the Dutch fascist party collaborating with the Nazi’s. Differently than in Europe, however, in Indonesia this antisemitic rhetoric and propaganda never evolved into an actual policy of extermination of Jews or the implementation of race-laws. As such, Captain explains, the process of coming to terms with the legacy of the holocaust was developed quite differently in Indonesia than in Europe, where it was a matter of collective self-examination, specifically tied to the European history and context. The products of this period, including rhetoric, propaganda and imagery, therefore underwent distinct processes of epistemological development, acquiring different cultural meanings in their respective collective memories.[2]

Kerstin Winking (left), Esther Captain, Alexander Supartono. Photo: Ju-An Hsieh

‘The developments represented a clear mismatch in communication of what the invited artists aimed to bring to documenta and the structure of support supposedly responsible for the accommodation of these aims’

In the same panel, Alexander Supartono, art historian, curator, and member of the Taring Padi collective himself, continued discussing the controversial imagery. He started by explaining Taring Padi’s methodology and how much of their work comes into being: the banners are produced in an anti-authorial, collective process, in which all members of the collective actively participate. Some set up outlines, some finish or continue on what someone else started, others focus solely on coloring or detailing. This process makes it hard to retrace the origins of any particular image in a work. Hundreds of these banners have been made over the past decades, featuring thousands of depictions of dehumanized caricatures which often address or represent supporters or delegates of the oppressive Suharto-regime and groups subjected to this regime. In Taring Padi’s artistic practice these banners often serve as a backdrop for public gatherings and protests, and Supartono even went as far as to argue that Taring Padi’s prolific production and consistent presence at protests have contributed to the fall of the Suharto-regime in 1998, when president Suharto stepped down after months of public protests.

According to Supartono, Taring Padi did not anticipate the sequence of events that was sparked by the exhibition of their banners in the for them completely novel context of modern-day Germany. Supartono considers each art work produced by Taring Padi to be a learning opportunity, which, he presumes, was also one of the qualities that landed the collective an invitation to participate in d15. He explained what happened when the assumed antisemitic imagery was spotted on the banner People’s Justice. Initially, the banner, which was located right in the center of the main documenta square in Kassel, was covered with a black cloth. The banner remained, however, towering over the square as a monument to erasure, a concretization of the dangers of censorship. Rather than facilitating a productive space for discussion, the documenta organization and board ordered the banner to be taken down entirely. Whereas Taring Padi and ruangrupa had intended the covering of the banner as an opening for discussion, and offered their public apology on the website of d15, their invitations to a dialogue were forcefully rejected. As Supartono lamented, these developments represented a clear mismatch in communication of what the invited artists aimed to bring to documenta and the structure of support supposedly responsible for the accommodation of these aims.

Leaning towards the progressive

In the second panel of the day, titled Lost in Translation: Discussing Art’s Place in a Polarised Public Discourse, Florian Cramer continued on this topic. He mapped and traced how the accusations of antisemitism could have become so amplified and ideologically instrumentalized in the German media. Reflecting on this, I believe the core of this issue lies at the German policy of crippling any critique on the state of Israel by claiming this to be antisemitic, thereby dangerously conflating the policies of the state of Israel with its people and religion.*[3] Cramer posed that this tendency is the result of Germany’s coming to terms with its own history. This has resulted in a general atmosphere in which critique on Israel has become suspect, under which banner rightwing groups in Germany, were able to instrumentalize this for their anti-Palestinian and implicit antimuslim agenda.[4] Cramer points out that d15 clearly provided space for critiques on the policies of the state of Israel, and that ruangrupa comes from an mostly Islamic country, this provided a perfect setting for many such attacks. With the appointment of ruangrupa as curators, and the inclusion of collectives such as Taring Padi, a decentralized (non)curator-model was implemented in which many voices from the non-European historic cultural space and idiom – bringing with them their respective local characteristics – were introduced. ‘It was’, Cramer concludes, ‘a shitstorm to happen’. He asked how it was possible that no-one from the organization or the board saw this cultural mismatch coming and why no one thought to prepare for such an inevitable clash.

Photo: Ju-An Hsieh

‘How was possible that no-one from the organization or the board saw this cultural mismatch coming and why did no one think to prepare for such an inevitable clash?’

Adding another perspective to the panel, Christa-Maria Lerm Hayes argued that each respective edition of documenta has always had a tendency towards the progressive. Founded as a postwar initiative intended to bridge the reinforced introduction of capitalism and modernist expansion to the needs of democratization, documenta is often politically motivated, leaning towards progressive processual activism. Lerm Hayes pointed at former documenta participant Joseph Beuys, whose art practice also manifested as membership and involvement with the Greenparty (die Grünen), as an obvious frontrunner of this progressive tendency. From documenta 12’s ‘The Migration of Forms’, documenta 13’s Artistic Research focus, to documenta 14’s expansion beyond Kassel to Athens which activated the political and conditional framework of art-making, Lerm Hayes traced an almost organic development towards d15, in which the logical next step would be the tackling of the overall western artworld and its conception of artistic practice. The relevance and need for such a manifestation is clear, she emphasizes, as throughout the artworld young artists and culture workers have declared themselves fed up with the capitalist model of art production which is based on competition, the artist as genius and the commodity-based economy of art handling.

As Lerm Hayes explained, this edition championed a more social and process-based mode of art production, which proved itself incompatible with the western art market, undermined its established system of critique, and clashed with the western political economy. Overall, the most prominent characteristic of this edition of documenta was how it dislodged itself from the capitalist mode of production. This in the end may be the more substantive accomplishment of d15, according to Lerm Hayes. She points out that ruangrupa aimed to concretely realize what western contemporary art critique has idealized for as long as it exists: a radical turn away from the commodity-based capitalist economy, and the address and critique of political hegemony. The question, however, is how this mode of production actually functioned in this edition of documenta, and how it could serve as a template for post-capitalist transformation.

Day 2: Rethinking institutional frameworks

The second day of the symposium, which took place at the Trippenhuis, tentatively delved further into the issues raised on day one. In the panel (re)Claiming Identities: Shaping and Framing Archives in an Institutional Context, the question was raised how European institutions can continue to stimulate and provide space for much-needed critical and multi-voiced discussions in an open, critical and equal way. The speakers in this panel provided various accounts of and perspectives on the political dependency that cultural productions face, and the necessity of re-organizing the facilitation and funding system.

In the first panel of the day, Mirjam Shatanawi, a scholar on Islamic visual culture and former curator of Middle Eastern and North African collections at the Tropenmuseum, explained how the legacy and cultural heritage of a people and how they are represented depends on their political formation. She gave the example of the issues she ran into when curating the exhibition Palestine 1948 in 2008. As there was no central Palestinian historical archive available, she was forced to look at other materials and sources of information, resorting to ‘informal’ means to represent the Palestinians.

Referring directly to his experiences at d15, Yazan Khalili, Palestinian architect, artist and cultural producer, and member and initiator of The Question of Funding, detailed in a very personal account how he was attacked at d15 for assumed antisemitism and the profound effect it had on him. The initiative The Question of Funding exposes and addresses the policies and regimes that underlie the funding of cultural production. In the exhibition presented at d15, The Question of Funding identified Germany’s anti-Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) policy – BDS was condemned by the Bundestag which halted all funding – as an ideological tool.[5] As Khalili is also a Palestinian, it made him a political target in different respects.

Eszter Szakács of the ROMAMOMA initiative, a long-term independent discursive art project that centers on the issue of artistic Roma representation and participant of d15, spoke about ROMAMOMA’s organizational issues. As a people, the Roma find themselves underrepresented and suppressed by the Hungarian state. She emphasized the need for an independent art-infrastructure that can function independently of the state’s power of control and funding. As representing a nationless people, a Roma-based artistic initiative is also largely dependent on supra-national efforts and organizational infrastructure. Like the other contributions to this panel, Szakács presented a distinct perspective and a convincing proposal for the reorganization of the current system of funding.

Gertrude Flentge (left), Lara Khaldi, Charles Esche and Ade Darmawan. Photo: Ju-An Hsieh

‘The continuation of the Lumbung principle is more important than upholding the relevance of the institute of documenta’

In the next panel, titled Other Ways of documenta-ing: Democracy, Inclusion, and Decolonised Models of Art, Lara Khaldi of the curatorial team of d15 and Gertrude Flentge, part of the artistic team of d15 with ruangrupa, explained the relevance of the concept of Lumbung as an egalitarian sustainable production based on the distribution of resources in dialogue. This model was then taken as primal goal from which the art would develop. Ade Darmawan of ruangrupa stressed that the foremost principle of d15 was the implementation of this new model of production, more so than simply setting up a large-scale exhibition. The intention of d15 was to test this process-based and curatorially delegated mode of production. Khaldi formulated this as a form of autonomy of production through resistance towards the institutional expectations that participation in documenta presented. For both Darmawan and Supartono, who chipped in from the audience, it was and remains unclear what this d15 has yielded, as they are still too involved with it in the moment. They expressed that for them, the continuation of the Lumbung principle is more important than upholding the relevance of the institute of documenta. They spoke of this documenta as ‘Lumbung1’, suggesting d15 may have become the mold for a new form of institution.

Towards a conclusion

The most pressing question is of course what the institutional and political relevance and legacy is of d15. What can be learned from it and how would this fit and add to the existing ideas of artistic and general production? As various speakers at the symposium emphasized, this documenta provided a watershed moment, in which the art world finally stepped away from the extractive, colonial, modernist mindset. To conclude, the symposium put forward roughly two main strands of critique on the political economy of art production, one derived from the principles of delegated curatorship and the other from a consistent processual dialogic and a collective approach, which I will discuss briefly.

First the principle of delegated curatorship. Many critics, even politically aligned artists, spoke of the partiality and representational imbalance of d15: why were there no Eastern Europeans/Ukrainians present?[6] Why were there no Israeli artist to counterbalance the suggestions and accusations of anti-Israeli bias? These objections miss however the beauty and critical importance of delegated authorship as was done by ruangrupa. The charm and political ambition of this edition’s delegated model is that it grows organically, and that it offers a manifestation of a potentiality of many iterations. In a sense the method of handing over curatorship, prevents any initial idea of intent to take control (or form of control to manifest). It radically empties the centrality and issue of curating as such.

Photo: Ju-An Hsieh

Secondly, d15’s consistent processual dialogic and collective approach. In the processual approach, each step is open to its reception, possibly affecting the initial gesture or position. It is a regenerative principle that de-authors. Lastly, this also means that the separation between categories and positions of labor (the division of labor) diffuses. The differences between artist, organizer, interpreter disappears, each are co-authorial instances of the same collective effort. The division of labor is one of the foremost means by which the capitalist order is kept intact, it prevents a coordinated response against the objectives set in capitalism, by keeping each and every worker in the chain responsible for his/her segments only. In other words, d15 demonstrated collectivity as model against capitalism’s focus on subjectification as medium of extraction.

It is important however to perceive the potential of this logic – the principle of collectivity – in a wider infrastructural sense. This entails in giving up on the traditional separation between the organization and the participating artists. To return to the issue of organization of d15 in the beginning of this text, it entails that the mediating role of the documenta organization cannot be separated from what ruangrupa brought to the table. It also means that the structures financing documenta should be interpreted as acting as a meta ‘curatorial’ organization. The funding parties therefore need to be brought into the conversation as well. If the aim truly is to fundamentally break down the myth of the autonomy of art, as well as the exceptional economy of art, the question remains how this potential may be returned to the political arena of institutions.

[1] https://www.frieze.com/article/diy-chaos-documenta-15-2022-review

[2] See also this article by Michael Rothberg: http://newfascismsyllabus.com/opinions/documenta/learning-and-unlearning-with-taring-padi-reflections-on-documenta/

[3] https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2019/kw20-de-bds-642892

[4] Some critics like Sultan Doughan and Hanan Toukan also argue that the adaptation of an exceptional claim to this history, serves to keep the colonial relationship between Europe and the Global South intact.

See: https://jacobin.com/2022/07/germany-israel-palestine-antisemitism-art-documenta?fbclid=IwAR256GpsOEmgj9XuNKhJ7z8OfnkbWA2I7ke5nKwGUqPEChv24ZNYaI-Rz8k

[5] Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) is a Palestinian-led movement promoting boycotts, divestments, and economic sanctions against Israel.

[6] This was the critique voiced by Dmitri Vilensky of Chto Delat.

* An earlier version of this text suggested that Florian Cramer made this argument, while it was actually the author reflecting on Cramers presentation. This has been corrected.

Jack Segbars