Installation, photo Gert Jan van Rooij, courtesy Centraal Museum

Beguiling and subversive – Pauline Curnier Jardin at Centraal Museum

At Centraal Museum, Pauline Curnier Jardin lets women assert their ‘superpowers’, shows men silently suffering from patriarchy and subverts the stereotypes surrounding menopause. ‘Maybe menopause is the last niche where capitalism cannot go. Maybe it’s some kind of haven from it.’

How often do you notice the smell when you walk into a space? It may be a personal quirk but for me, smell often comes to the forefront when interacting with my surroundings. It elicits distinct, almost primordial memories and emotions. My initial encounter with the works by the French artist Pauline Curnier Jardin (b.1980, Marseille) at the Centraal Museum Utrecht begins with the smell. Walking into the darkened Exhibition Room 8, I was immediately enveloped in a cloud of perfumed air. It smells of something floral, or perhaps like frankincense only less smokey. A sweet smell of wax and decay. Subtly, the scent sets the tone for the exhibition – under the alluring façade, something wicked this way comes.

Hot Flowers & Warm Fingers collects and features work by Curnier Jardin from the past five years to create her first solo exhibition in the Netherlands. The Amsterdam-Berlin-based contemporary artist is known for her transgressive, humorous, campy, and character-driven work in a wide range of forms from paintings, and performances to films and installations. She often incorporates historical and mythological elements to construct a surreal and cryptic visual language. Being particularly interested in the (mis)representations of people who identify as women in popular media, a lot of Curnier Jardin’s work included in this exhibition recuperates and subverts those stereotypes to reexamine and challenge the power structures in Western histories.

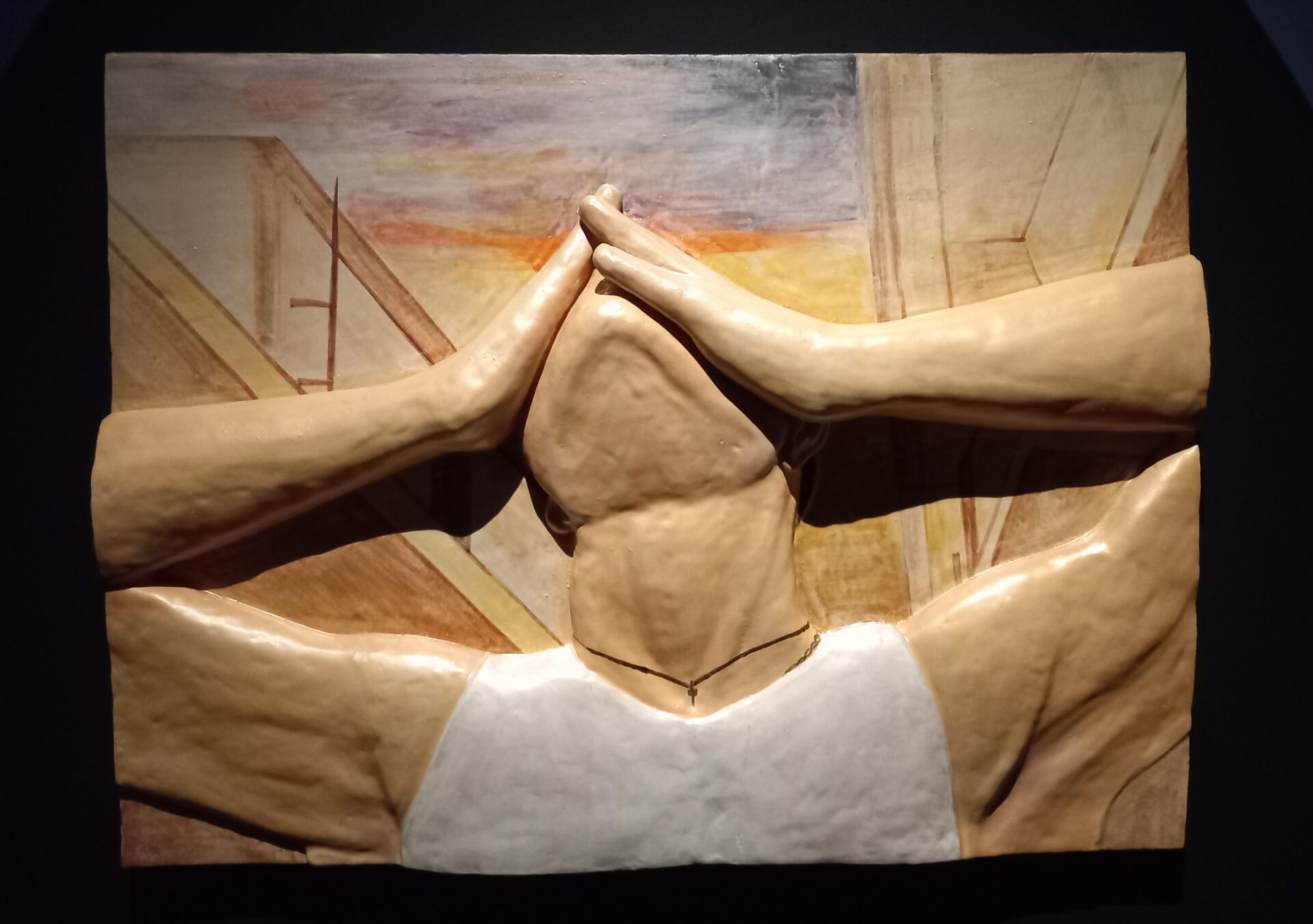

The first installation features a series of bas-reliefs depicting scenes from Curnier Jardin’s video works about Catholic traditions and rituals. She is known to work with unique representational logic in her artistic creations and here the logic seems to lie in the open. Bas-reliefs have been used in art since Ancient Egypt and later gained their association with classical and religious art in Europe. The use of bas-reliefs combined with motifs such as candles and altars spell out the religious codes in her work.

Pauline Curnier Jardin, intsallation Centraal Museum Utrecht, 2023, photo Metropolis M

Pauline Curnier Jardin, 18' 09' 10' (Fat to Ashes), 2023, photo Metropolis M

The votive candle stand in front of the bas-relief of Explosion Ma Baby (2023) adds both visual and narrative complexity to the room. The candles are comically long and even though none of them was ever lit, they somehow give out a half-melted appearance, with the ones on each side bent away from the center. There is also melted wax at the bottom of the two trays, forming uncanny and somewhat horrific resemblances of a male and a female figure. Who are they? A wacky representation of Adam and Eve? But perhaps their anonymity serves other narratives. The male figure is directly under the candles, on a higher register than the female figure, whose melted body is mingled with coins. Placed in a religious setting, this arrangement seems to comment on the gendered hierarchy of Catholicism, with the man being closer to the candles and thus closer to the holy light. But the distorted, melted, sagging woman also directly reflects the social anxiety over the depiction of the ageing female bodies, a central theme in Curnier Jardin’s work that reappears throughout the exhibition. If the traditional votive candles create a sense of peace and hope, Curnier Jardin’s campy candles create discomfort and uncertainties, providing more questions than answers.

The artist’s contemplation on religion, religious propaganda, and the consumption of the female body continues into the next room. A brand new multi-media installation was created for the Centraal Museum as the first part of an initiative titled ‘Another Story’ to revitalise the museum’s collection. It brings to mind the Great Hall Commission at the Metropolitan Museum where artists are invited to create new work in dialogue with the Met’s collection and its physical environment. I was glad to find out that the Centraal Museum, dedicated to making its space more accessible, has already created an extensive online platform for people to explore the collection digitally. ‘Another Story’ provides another innovative way for contemporary audiences to review, revisit, and find new ways to relate to historical artworks and artifacts.

This ambitious ‘Wunderkammer’ installation incorporates multiple mediums such as paintings, artifacts, furniture, video, and soft sculptures to create an enigmatically coded world. It is a room filled with juxtapositions – between masculinity and femininity, softness and hardness, utility and the decorative. Two paintings depicting Saint Sebastian from the 1600s by two native Utrecht artists are placed in dialogue with Curnier Jardin’s teaser video for her film Sebastiano Blu (2019). Set at an unknown location in the Mediterranean, we follow Giorgetto, a rather celebrated young man in town and a local DJ, whose seemingly comfortable life is plagued by insecurities over fertility, gender relations and socio-economic hardships. Still living with his parents with no real independence and suffering from anxieties about the opposite sex, he starts to believe that menopausal women possess superpowers. Their infertility is ordained by nature, a part of the human life cycle, and thus they are freed from the societal expectation of bearing children. Whereas Giorgetto’s possible inability to father offspring puts him under the scrutiny of a highly patriarchal society.

Pauline Curnier Jardin, 'La Vase Magique (Viola Melon, Baiser Melocoton)' (2014). On view in 'Hot Flowers, Warm Fingers' at Centraal Museum, Utrecht. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

This ambitious ‘Wunderkammer’ installation incorporates paintings, artifacts, furniture, video, and soft sculptures. It is a room filled with juxtapositions – between masculinity and femininity, softness and hardness, utility and the decorative

Pauline Curnier Jardin, selection of furnitute and paintings from the collection of Centraal Museum. On view at 'Hot Flowers, Warm Fingers', Centraal Museum, Utrecht. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

The reference to Saint Sebastian in the video is teased out by the coupling of the historical paintings. Placed in context with Giorgetto’s story, Saint Sebastian is sympathetic to our protagonist, full of wounds and suffering. Like Saint Sebastian, Giorgetto suffers in silence, hushed by the larger socio-economic and cultural structures that allow no space for vulnerability in masculinity. But his ‘martyrdom’ might not earn him the status of a saint. What is refreshing in Giorgetto’s story is that while reflecting on how women, especially ageing and sexually active women, have been historically demonised in popular media, Curnier Jardin also examines how men could be victims of the patriarchy as well, a perspective not often discussed by feminist artists.

The video is displayed in a constructed living-room-like space, in front of several pieces of furniture from the museum’s collection. However, visitors are instructed not to step onto the floorboard or touch any furniture, resulting in a rather awkward video-viewing experience. Was it a strategy of Curnier Jardin and the curators to put viewers in discomfort to simulate the experience of women in domestic spaces who are often not the ones sitting in front of the TV? Whether intentional or not, the lack of seating led to many visitors quickly walking away from the video, making it less accessible to its audience. Even though we are not allowed to sit on the sofa, it is not unoccupied. A piece of soft beige-tone leather in the shape of a female body lounges on, or rather, is thrown over the pink sofa. These Peaux de Dame (2018) created by Curnier Jardin resemble soft, flat women figures that could be rolled up, pinned on the wall as decorations, or draped over tired furniture (Curnier Jardin, 2018). Their softness and malleability contrast the hardness of the cabinet, the shelf, and the chairs. At the same time, their decorativeness stands against the unusability of the furniture, teasing out a critique of the misogynistic association made between women and decorative objects.

Pauline Curnier Jardin, intsallation Centraal Museum Utrecht, 2023, photo Metropolis M

In Adoration, Curnier Jardin worked with women from a women’s prison in Venice that used to be a convent in the sixteenth century

Pauline Curnier Jardin, 'Le Tombeau' (2022). On view in 'Hot Flowers, Warm Fingers' at Centraal Museum, Utrecht. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

In each installation of the exhibition, Curnier Jardin creates fictional world(s) that question stereotypes and ritualistic performances in the West. In Adoration (censored version, 2022), coproduced by the Centraal Museum and premiered in Venice last year, Curnier Jardin worked with women from a women’s prison in Venice that used to be a convent in the sixteenth century. The women who were forced to go to the convent were mostly those who did not marry at a marriage age or were sex workers. This project explores how historically women have been mistreated and marginalised for not conforming to the norms, and how creativity could offer them salvation to break free from physical and societal constraints. The link between religious tradition and art is also echoed in the history of the Centraal Museum, which used to be the convent of St. Agnes, the patron saint of chastity and purity. The parallelity between the two convents adds an extra layer of irony to the narrative of the film.

A missable component of the installation exemplifies the intentional muddiness of Curnier Jardin’s reconstructed histories and mythologies. On the back wall in the room, there is a window that ‘looks out’ to a sterile hallway in the women’s prison with notices regarding mask hygiene, yanking the audience back from the sixteenth century to the recent Covid pandemic. It serves as a time stamp for a room that seems to travel back and forth between the past and the present. However, I couldn’t help but wonder if the masking and the quarantine are another element in this narrative of restraints. If so, where does creativity come into play in this particular dynamic?

Pauline Curnier Jardin, 'Hot Flower Forest' (2023, in front) and 'Qu’un Sang Impur' (2019, in the back). On view at 'Hot Flowers, Warm Fingers', Centraal Museum, Utrecht. Photo: Gert Jan van Rooij

The recurring themes of female sexuality, reproductive power, and demonisation of the ageing bodies in Curnier Jardin’s work all come together in what seems to be the crowning piece of the exhibition – an installation consisting of the film Qu’un Sang Impur (2019) and the theatre set Hot Flower Forest (2023). Curnier Jardin plays with the colour red in this room. The red roses and hydrangeas symbolise youth and beauty while eliciting an association with Valentine’s Day and thus with love and lust. The floor is also painted red, a shiny, reflective red that calls to mind a pool of blood, creating a sensuous but sinister ambience that foreshadows the story of the film. In Qu’un Sang Impur, Curnier Jardin seems to channel Audre Lorde’s ‘the erotic as power’ to subvert the stereotypes surrounding menopausal women. For Lorde, the erotic pertains to the lifeforce of women, the empowered creativity and a reclaiming of love and life. The portrayals of the women in this film move away from the archetypes of witches and hags and spotlight their sexuality, youth, and desires. They are not completely free from the male gaze with the inclusion of the peeping-tom prison guard character, but they choose to ignore him and even openly defy him, reclaiming their space of freedom through the expression of the erotic.

Curnier Jardin also blurs the line between the perpetrator and the victim in this film, taking on a sympathetic stance with the murderers. In an interview with Isabelle Massu in 2019, she talks about envisioning a menopausal horror movie where older women go on a killing spree seeking vengeance for young women who have been harassed, a narrative partially realised in Qu’un Sang Impur. Blood seems to be central to both the visual and the subtext of this work. The depiction of period blood and the bloodbaths of the murders play into the tropes of horror flicks and exploitation movies, adding an element of campiness that is so idiosyncratic to Curnier Jardin’s visual language. At the same time, by taking the life-giving blood that is also associated with reproduction and sexual desires, the women in the film assert their ‘superpowers’ and claim over life itself.

When I visited the Centraal Museum, sections of the building were closed for installation, so I had to exit Curnier Jardin’s exhibition through Room 8. But this slight inconvenience turns out to be quite a brilliant way to conclude my experience. It forces the visitors to retrace their footsteps, seeing the five installations as a whole. Through this second viewing, we are encouraged to rethink the relationships between each installation and get a better grasp of some of the central themes. Curnier Jardin’s work is not easy to interpret, said her gallerist Ellen de Bruijne in an interview. They form a maze full of references and the key lies tangled in her personal experience and mythologies. But their vagueness and density make viewing her work an intellectually enjoyable experience and create room for ambiguity and discussion. After coming back to Room 8, the smell I encountered first seems to have become less sinister and much sweeter.

Hot Flowers & Warm Fingers is on view at Centraal Museum, Utrecht, until April 21, 2024

Monica Liu

is kunsthistoricus en -criticus